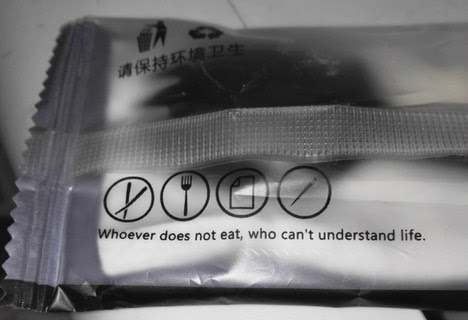

"Whoever does not eat, who can't understand life"

« previous post | next post »

Two images of Chinese takeaway packages in Beijing from Teresa Norman:

Usually, when we study Chinglish, we hope for a Chinese parallel or source text to help us understand what it means or how it came to be what it is. In these two cases, we can see that Chinglish has taken on a life of its own. We may not know exactly what they mean, but each in its own way is delightful.

The first example stimulates us to contemplate a fundamental verity of human existence, and the second tickles our fancy with its fascinating choice of words.

Ah, the vibrant whimsy and gnomic wisdom of stand-alone Chinglish!

Chas Belov said,

February 2, 2019 @ 4:35 am

There's the whimsy of the choice of images as well on the first one:

– chopsticks

– fork

– print side down?

– ???

Jamie said,

February 2, 2019 @ 4:50 am

@Chas Belov I think the last two are paper towel and toothpick!

Anne Henochowicz said,

February 2, 2019 @ 5:18 pm

I think you can reverse-engineer the first one, kind of. It harkens back to the shéi VP1, shéi VP2 construction, eg. "He who does not eat (savor?) does not understand (appreciate?) [the meaning of] life." "Eat" feels like the wrong verb, though – if you don't eat, lack of understanding is the least of your problems.

Michael Watts said,

February 2, 2019 @ 6:41 pm

I agree with Anne Henochowicz – the Chinese behind this is quite transparent. 谁不吃,谁懂不了人生。 (I'm just guessing, probably badly, as to the phrasing of "can't understand life", but that is perfectly idiomatic English and so doesn't really present any problems.)

English and Latin bind variables in sentences using dedicated question/answer words. Compare quantus "how many?" and tantus "that many" / qualis "like what?" and talis "like that" / quis "who?" and is "he".

Chinese doesn't do that. Instead of a question/answer pair, variables are bound with a question/question pattern, repeating the question word. In English, we say "whoever passes first, that person begins the next round", but Chinese syntax calls for "who passes first, who begins the next round". The translator here has learned that this construction requires the -ever suffix in English, but has failed to replace the Chinese question word in the second clause with an English answer word. It should be "Whoever does not eat, they can't understand life".

Victor Mair said,

February 3, 2019 @ 8:41 am

The grammatical pattern underlying the English is definitely "shéi bù 谁不…, shéi bù 谁不…." ("whoever doesn't… [that person] doesn't / cannot….", which I noticed when I first saw this photograph, so I was happy when Anne Henochowicz pointed this out for everybody.

chris said,

February 5, 2019 @ 7:29 pm

English also allows dropping the pronoun in the second phrase: whoever does not work does not eat.

Rewriting the English this way can give you "whoever does not eat does not live", which produces a double meaning between the literal meaning (die of starvation) and the figurative meaning (you're not living life to the fullest if you're not appreciating the joy of food, which I presume is the intended message on a commercial food package).

Or should that be more like "preserves" a double meaning? Does Chinese allow a similar ambiguity between "understand life" in the sense of appreciation, and in the sense of survival? And was something like that in the mind of the designer before they tried to translate their thoughts into English?

In any language there's a difference between living the good life and just not being dead — but food is essential to both.