Style shifting in student writing assignments

« previous post | next post »

Along with Valerie Ross, Brighid Kelly, and Helen Jeoung from Penn's Critical Writing program, I've been looking at material from student writing assignments (as part of an NSF-funded study*). One of the many topics of interest is the extent to which students, collectively and individually, succeed in shifting their writing style to suit different genres and audiences. As a first trivial exploration of this question, I took a quick look at some simple properties of overall word choice, comparing submissions to two different types of assignment. One of these assignments is a "Public Argument", which I believe is something like a newspaper Op-Ed; the other is a "Literature Review", where the appropriate style is more academic.

This morning I'll look at some of the simplest results of two simple explorations of properties that should be related to style shifting — the choice of words, and the length of the words chosen.

To support a quick exploration of word choice, I created lists of word counts from all the submitted assignments so far processed (3,615 "public arguments" comprising 2,558,730 words, and 1,200 "literature reviews" containing 1,303,434 words). "Processed" here means fixing up the text derived from .pdf submissions to eliminate headers, footers, spurious blank lines, etc. — so far this dataset includes all of the "public arguments" and about half of the "literature reviews" from one year's collection.

I then tried two simple things. First, I calculated the "weighted log-odds-ratio, informative Dirichlet prior" for all the words from both assignmentds, using the algorithm described on p. 387-8 of Monroe, Colaresi & Quinn "Fightin' Words: Lexical Feature Selection and Evaluation for Identifying the Content of Political Conflict", Political Analysis 2009. For some earlier uses of this method, see "Obama's favored and disfavored SOTU words", 1/29/2014; "Male and female word usage", 8/7/2014; "The most Trumpish (and Bushish) words", 9/5/2015.

The 20 words most indicative of the "Public Arguments" collection turned out to be

you I we your my our should it if not students are Trump be children do will just can would they so me to child

And the top 20 for the "Literature Reviews":

scholars field research the of studies study creativity et al between literature researchers Chaplin review argues nanotechnology in analysis article

We obviously want to ignore the topic-specific words like Trump, Chaplin, and nanotechnology. Among more general words, it's not surprising that first- and second-person pronouns are featured in the "public argument" dataset; similarly the modals should, will, can, would make sense. It's a bit less obvious that are, be, do should be featured there, and similarly it, if, not, though in retrospect we can imagine why this might be true.

It's consistent with a variety of previous results that the and of are more common in more formal writing — see e.g. "Decreasing definiteness", 1/8/2015; "Why definiteness is decreasing, Part 1 … Part 2 … Part 3"; "The case of the disappearing determiners", 1/3/2016; "Decreasing definiteness in crime novels", 1/21/2018. And broad content-related words like scholars, field, research, study are obviously expected.

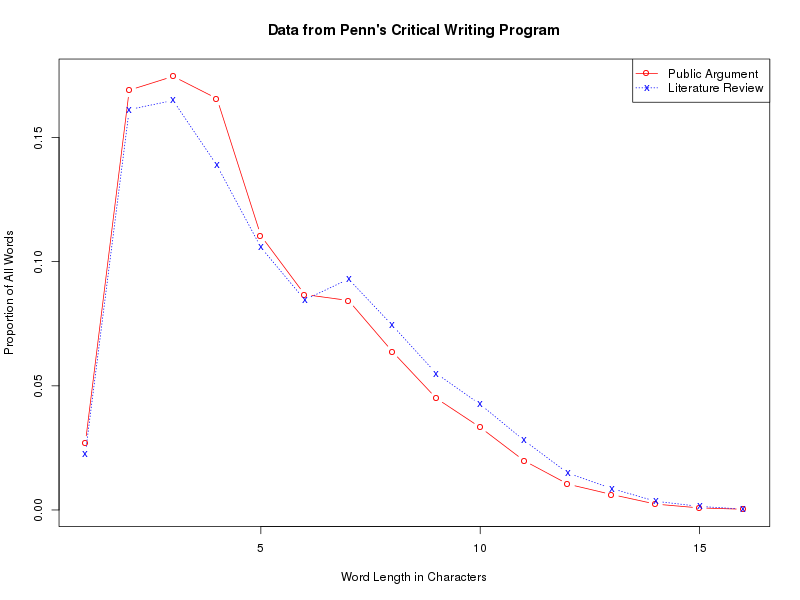

Then I took a quick look at the distributions of word lengths (in letters). One fact about these distributions is completely unsurprising — the more informal genre has more short words and fewer long ones:

FWIW, the overall mean word length for the public arguments is 4.94 letters, and for the literature reviews it's 5.28 letters. The direction of the difference is not surprising, though we might have expected it to be larger.

But it was news to me that there's an apparent discontinuity between 6 and 7, in both datasets and especially in the reviews — and I wonder whether this is a general fact about English text, or something special about this dataset (or my tokenization methods, or whatever).

On a quick scan, it looks like this has something to do with the frequency of some 7-character words. Thus in the two collections combined, here are the most frequent 10 6-letter words:

2769 people

2243 social

1207 public

1109 within

1061 during

958 states

952 health

895 should

862 theory

841 mental

And here are the most frequent 7-letter words:

3149 between

2541 studies

2155 however

2039 through

1895 because

1470 example

1105 article

1078 effects

1035 society

1003 results

But there's obviously more to say about this…

Update — I should add that these preliminary explorations are part of the background for a more substantive analysis that's on the project's agenda, namely to look for stylistic issues in individual submissions and to relate them to comments in the peer and instructor evaluations.

*NSF grant 15444239 to Valerie Ross, "Collaborative Research: The Role of Instructor and Peer Feedback in Improving the Cognitive, Interpersonal, and Intrapersonal Competencies of Student Writers in STEM Courses".

Doug said,

October 5, 2018 @ 10:39 am

The first list of "7-character words" appear to consist of 6-character words.

(people, social …)

[(myl) Oops, wrong illustration and explanation — fixed now…]

mg said,

October 5, 2018 @ 2:02 pm

Is there any way to get "et al" to count as one unit? I think it makes the results of both frequency and word length less informative to count each separately when they never occur apart. Perhaps a simple script to replace "et al" with "etal" or "et-al" could be used in pre-processing.

[(myl) That could certainly be done, but it's not going to change anything important. "Et al." occurs 1,224 times, 0.2% of the 642,764 2-letter words. There are lots of fixed phrases that could (and probably should) be considered as single tokens, like "instead of" (which occurs 1,983 times)]

David Morris said,

October 5, 2018 @ 4:59 pm

Who or what is 'chaplin' in the academic list?

Alyssa said,

October 5, 2018 @ 6:36 pm

@David Morris

It could be misspelling of chaplain – most universities have a chaplain who is essentially the head of religious services on campus.

Otherwise, the only thing I can imagine is that some of the Literature Reviews discussed Charlie Chaplin for some reason, and it stuck out statistically the same way "trump" did on the public argument list.

bks said,

October 5, 2018 @ 8:49 pm

Why "nanotechnology"?

[(myl) Like Chaplin and some of the other words, this is because of one of the assigned topics in one (or more) of the sections of the course. An obvious issue in this kind of analysis is how to distinguish topic-related words from stylistic choices.]

Jen in Edinburgh said,

October 6, 2018 @ 4:44 am

I would guess that the assignment was to write a literature review on a particular topic, and that Chaplin (or Chaplin et al) wrote the big paper(s) in that area.

[(myl) It was Charlie Chaplin, actually — some of the course sections had film as a theme.]

Rick Robinson said,

October 6, 2018 @ 11:36 am

Completely tangential to the topic, but the two lists of most common words have a curious effect when read. The Literature Review word list, with just a couple of exceptions, yields almost meaningful-sounding snippets:

scholars field research …

studies study creativity et al between literature researchers

Chaplin review argues nanotechnology in analysis article

The Public Argument word list is more discursive, producing snippets less grammatical, but oddly evocative and poetic:

you I we your my our

if not students are Trump be children do will just can

would they so me to child

Even though both list sequences are pure artifacts of word frequency in the source texts, these pseudo-phrases seem consistent with the stylistic differences you would expect between these genres.

Orin K Hargraves said,

October 6, 2018 @ 5:38 pm

Interesting analysis and I look forward to more. One thing that puzzles me in undergrad writing is that someone (in high school?) is still giving them the memo about the passive voice being a really cool thing that makes your writing sound better–because it almost never does. I have seen it particularly in what they consider to be formal writing: literature reviews, papers arising from their own research.

Robot Therapist said,

October 7, 2018 @ 1:43 am

Oh no! Don't mention passive voice here!

Philip Taylor said,

October 8, 2018 @ 1:26 pm

I am one of the generation(s) into whom/which the use of the passive voice was intentionally and carefully inculcated, and for the purpose(s) for which its use was recommended (reports of experiments, etc., in which the rôle of the experimenter as individual is of no consequence), I still consider it the preferred form and use it accordingly.