The factual impenetrability of zombie rules

« previous post | next post »

Frank Bruni, "What Happened to Who?", NYT 4/8/2017:

I first noticed it during the 2016 Republican presidential debates, which were crazy-making for so many reasons that I’m not sure how I zeroed in on this one. “Who” was being exiled from its rightful habitat. It was a linguistic bonobo: endangered, possibly en route to extinction.

Instead of saying “people who,” Donald Trump said “people that.” Marco Rubio followed suit. Even Jeb Bush, putatively the brainy one, was “that”-ing when he should have been “who”-ing, so I was cringing when I should have been oohing.

It’s always a dangerous thing when politicians get near the English language: Run for the exits and cover the children’s ears. But this bit of wreckage particularly bothered me. This was who, a pronoun that acknowledges our humanity, our personhood, separating us from the flotsam and jetsam out there. We’re supposed to refer to “the trash that” we took out or “the table that” we discovered at a flea market. We’re not supposed to refer to “people that call my office” (Rubio) or “people that come with a legal visa and overstay” (Bush).

Or so I always assumed, but this nicety is clearly falling by the wayside, and I can’t shake the feeling that its plunge is part of a larger story, a reflection of so much else that is going wrong in this warped world of ours.

According to the 1989 Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage [emphasis added]:

In current usage, that refers to persons or things, which chiefly to things and rarely to subhuman entities, who chiefly to persons and sometimes to animals. That is definitely standard when used of persons.

MWDEU explains the history of Bruni's peeve (though not its passionate intensity, for which see "The social psychology of linguistic naming and shaming"):

When that came back into literary use around the beginning of the 18th century after falling out of favor during the 17th, it was noticed with some disapproval […] by such writers as Joseph Addison. Jespersen 1905 points out that the expressed preference for who and which may have come partly from their conforming to the Latin relative pronouns (that having no Latin correlative). Jespersen also notes that when Addison edited The Spectator to appear in book form, he changed many of his own uses of that to who or which.

The 18th century also marks the first appearance of works devoted to the correction of English usage; some, naturally, discussed relative pronouns. McKnight 1928 cites an anonymous 1752 Observations upon the English Language (George Harris wrote it, says Leonard 1929), which condemned the use of that and prescribed who as "the only proper Word to be used in Relation to Persons and Animals" and which "in Relation to Things." It may be that some carryover from the 18th-century general dislike of that has produced the apparently common, yet unfounded, notion that that may be used to refer only to things. Bernstein 1971 and Simon 1980 mention receiving letters objecting to the use of that in reference to persons. The notion persists: we have heard of a professor of political science in California whose class stylesheet (in 1984) insisted that could only refer to things, and William Safire in the New York Times Magazine (8 June 1980) panned an ad beginning "We seek a managing editor that can…." That has applied to persons since its 18th-century revival just as it did before its 17th-century eclipse.

Although examples like those that make Frank Bruni cringe have been normal parts of the English language for more than 500 years, he sees this aspect of Donald Trump's usage as "a reflection of so much else that is going wrong in this warped world of ours", and closes with this (apparently not ironic) apocalyptic vision:

And my fear is that there’s a metaphor here: something about the age of automation, about the disappearing line between humans and machines. The robots are coming. Maybe we’re killing off “who” to avoid the pain of having them demand — and get — it.

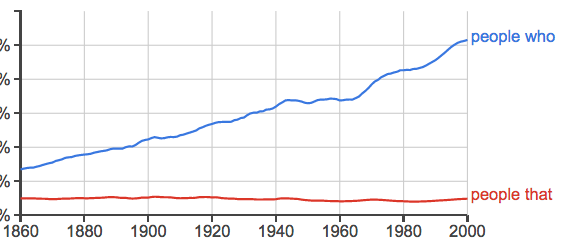

In the first place, it's really not obvious that anything has changed other than Frank Bruni's annoyance level. I don't have time today to program a proper search of historical treebanks for the proportions among who, that, and 0 in relative clauses with human heads. But Google Ngrams searches for some common cases do not clearly show that "we're killing off 'who'":

And public figures in the middle of the 20th century, 20 years before Frank Bruni was born, were routinely using that in relative clauses with human heads, even in circumstances of sentimental focus on human connections. Thus Dwight D. Eisenhower, "Homecoming Speech", 1945 [emphasis added]:

Because no man is really a man who has lost out of himself all of the boy, I want to speak first of the dreams of a barefoot boy. Frequently, they are to be of a street car conductor or he sees himself as the town policeman, above all he may reach to a position of locomotive engineer, but always in his dreams is that day when he finally comes home. Comes home to a welcome from his own home town. Because today that dream of mine of 45 years or more ago has been realized beyond the wildest stretches of my own imagination, I come here, first, to thank you, to say the proudest thing I can claim is that I am from Abilene.

Through this world it has been my fortune or misfortune to wander at considerable distance; never has this town been outside my heart and memory. Here are some of my oldest and dearest friends. Here are men that helped me start my own career and helped my son start his. Here are people that are lifelong friends of my mother and my late father, the really two great individuals of the Eisenhower family. They raised six boys and they made sure that each had an upbringing at home and an education that equipped him to gain a respectable place in his own profession, and I think it's fair to say they all have. They and their families are the products of the loving care, labor and work of my father and mother; just another average Abilene family.

But the most interesting thing about Bruni's column is that he does enough research to discover that his peeve is contradicted by the history of English writing, and also by usage authorities aside from cranks like Mary Norris — but he peeves ever onward.

Maybe he just had a column to push out, and no other ideas on tap.

But impenetrability to fact is a common characteristic of zombie rules — committed peevers shed counterexamples like hailstones off a tin roof. This resistance to disconfirmation by experience, going well beyond mere confirmation bias, seems to be part of the dynamics of social stereotypes in general, including those that are far more destructive than mere animus against human that.

Still, for those of us outside the fold, here's a random fistful of other examples over the centuries:

Sir Philip Sidney, The Defense of Poesie, 1583:

For as in outward things to a man that had neuer seene an Elephant , or a Rinoceros, who should tell him most exquisitely all their shape, cullour, bignesse, and particuler marks, or of a gorgious pallace an Architecture , who declaring the full bewties, might well make the hearer able to repeat as it were by roat all he had heard, yet should neuer satisfie his inward conceit, with being witnesse to it selfe of a true liuely knowledge […]

William Shakespeare, Twelfe Night, 1623:

I am no fighter, I haue heard of some kinde of men, that put quarrells purposely on others, to taste their valour: belike this is a man of that quirke.

George Chapman, The Crowne of All Homers Workes, 1624:

And without Truth, all's onely sleight of hand,

Or our Law-learning, in a Forraine Land;

Embroderie spent on Cobwebs; Braggart show

Of Men that all things learne; and nothing know.

Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler, 1653:

There are many men that are by others taken to be serious grave men, which we contemn and pitie; men of sowre complexions; mony-getting-men, that spend all their time first in getting, and next in anxious care to keep it: men that are condemn'd to be rich, and alwayes discontented, or busie.

Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders, 1722:

As for Women that do not think their own Safety worth their own Thought, that impatient of their present State run into Matrimony, as a Horse rushes into the Battle; I can say nothing to them but this, that they are a Sort of Ladies that are to be pray'd for among the rest of distemper'd People, and they look like People that venture their Estates in a Lottery where there is a Hundred Thousand Blanks to one Prize.

John Cleland, Fanny Hill, 1748:

I being actually hired under the nose of the good woman that kept the office, whose shrewd smiles and shrugs I could not help observing, and innocently interpreted them as marks of her being pleased at my getting into place so soon.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, 1803:

It was too dirty for Mrs. Allen to accompany her husband to the pump-room; he accordingly set off by himself, and Catherine had barely watched him down the street when her notice was claimed by the approach of the same two open carriages, containing the same three people that had surprised her so much a few mornings back.

Jane Austen, Emma, 1815:

She is a woman that one may, that one must laugh at; but that one would not wish to slight.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses", 1842:

Death closes all; but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son, 1848:

'And as you've known me for a long time, you know,' said Mr Toots, 'let me assure you that she is one of the most remarkable women that ever lived.'

Herman Melville, Moby Dick, 1851:

I know a man that, in his lifetime, has taken three hundred and fifty whales.

Mark Twain, Roughing It, 1872

He was one of the best and kindest hearted men that ever graced a humble sphere of life.

Mark Twain, Life On the Mississippi, 1883

Then the man that had started the row tilted his old slouch hat down over his right eye; then he bent stooping forward, with his back sagged and his south end sticking out far, and his fists a-shoving out and drawing in in front of him, and so went around in a little circle about three times, swelling himself up and breathing hard.

Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 1885:

Because you're brave enough to tar and feather poor friendless cast-out women that come along here, did that make you think you had grit enough to lay your hands on a man?

Bram Stoker, Dracula, 1897:

It was as though my memories of all Jonathan's horrid experience were befooling me; for the snow flakes and the mist began to wheel and circle round, till I could get as though a shadowy glimpse of those women that would have kissed him.

Joseph Conrad, Nostromo, 1904:

Their sentiment was necessary to the very life of my plan; the sentimentalism of the people that will never do anything for the sake of their passionate desire, unless it comes to them clothed in the fair robes of an idea.

G.K. Chesterton, The Innocence of Father Brown, 1911:

They were English hands that dragged him up to the tree of shame; the hands of men that had adored him and followed him to victory.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan of the Apes, 1912:

The Moors were essentially a tolerant, broad-minded, liberal race of agriculturists, artisans and merchants—the very type of people that has made possible such civilization as we find today in America and Europe—while the Spaniards—

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises, 1926:

At the gate of the corrals two men took tickets from the people that went in.

Margaret Mitchell, Gone With The Wind, 1936:

[I]f you weren't always so busy looking for the good in people that haven't got any good in them, you'd see it.

Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls, 1940:

He was violating the second rule of the two rules for getting on well with people that speak Spanish; give the men tobacco and leave the women alone; and he realized, very suddenly, that he did not care.

Josephine Tey, Miss Pym Disposes, 1946:

Even in Larborough, it was to be supposed, there were people that one might conceivably be going to see.

Vicki said,

April 9, 2017 @ 6:50 am

E. B. White wrote somewhere of having seen a complaint about this same usage, and offering as refutation the King James Bible, a translation which a significant number of people believe(d?) to have been divinely guided: "Where is He that is born king of the Jews?

I am also certain that virtually all of the people who object to Donald Trump (and the majority of those who dislike Rubio and Trump, for that matter) have larger grounds for doing so than his grammar. Yes, it's probably at the stage where many people would complain "look at him, wearing that hat!" when they wouldn't even blink at the same hat, in the same context, on a friend. But the flaw isn't in the hat, or the pronoun choice.

Edwin Schmitt said,

April 9, 2017 @ 7:58 am

This is a completely off topic comment but there is an outstanding simile you used that I have never heard before: shed X [counterexamples] like hailstones off a tin roof. Growing up in rural Western Montana I would hear similes like this all the time. I have often wondered if anyone has compared the use of simile in rural vs. urban communities in the US. By chance are you from a rural part of the Northern US?

Joyce Melton said,

April 9, 2017 @ 8:22 am

I perceive, perhaps wrongly, a subtle difference between the usage of who/which and that. To my ear, who/which directs attention to the first part of the sentence and that shifts it to the following part.

"Where is He who is born king of the Jews?" is a different question than the same phrasing with that. Who would most likely be used as a label, to identify which particular God you are looking for. That can be used as a consequent explanation, a reason to be looking for a God.

I have an editor who changes a large fraction of my thats to whos and whiches, and I change a major percentage of them back.

I may be wrong on this but I perceive it as a useful distinction.

[(myl) In modern usage, that is almost entirely restricted to restrictive relative clauses, while who can be either restrictive or non-restrictive. This difference may generate a feeling that clauses introduced with who are more independent, and thus more independently salient.]

ffrancis said,

April 9, 2017 @ 8:48 am

I assumed (without, admittedly, putting any deep thought into it) that any rising use of "that" in the public language, verbal or written, of politicians was rooted in the fear of mockery for using "who" when they should have used "whom", a possibility that the substitution of "that" avoids.

[(myl) If such a rise has happened, my guess is that it was a century ago or so…]

Keith Clarke said,

April 9, 2017 @ 10:05 am

Edna St Vincent Millay, Song of a Second April, 1923 –

Among the mullein stalks the sheep

Go up the hillside in the sun,

Pensively,–only you are gone,

You that alone I cared to keep.

Surely no-one ever read that, and winced because it didn't say "You who.."

RP said,

April 9, 2017 @ 10:36 am

There's an alternative zombie rule according to which "which" should be used in non-restrictive contexts, "that" in restrictive ones. At least some usage writers have suggested that "who" should also be used in non-restrictive contexts, "that" in restrictive ( http://www.bartleby.com/116/205.html ). The funny thing is, this zombie rule and the "who for people, that for objects" zombie rule are completely incompatible with each other.

Jonathon Owen said,

April 9, 2017 @ 11:43 am

Gabe Doyle had a couple of good posts on that and who several years back:

People that need people I: a history of that/who

People that need people II: the subject-object distinction

And here's something I wrote on it a few years ago.

I wonder what these peevers think of the fact that the Germanic languages primarily use demonstratives (in other words, forms of that) as relative pronouns while the Romance languages primarily use interrogatives. Is German more dehumanizing than French because Germans say "die Leute die" rather than "die Leute wer"?

Rodger C said,

April 9, 2017 @ 11:54 am

I've often cringed at modern-English liturgies, all seemingly written by people whose self-qualification for writing English is that they're ordained, that make me say "yoo-hoo take away the sin of the world."

rcalmy said,

April 9, 2017 @ 11:56 am

"The funny thing is, this zombie rule and the 'who for people, that for objects' zombie rule are completely incompatible with each other."

This seems characteristic of the breed. I suspect if anyone actually seriously tried to follow all the zombie rules, they would find themselves limited to Dick and Jane levels of prose.

Viseguy said,

April 9, 2017 @ 12:10 pm

@Keith Clark: Plus, "you that" avoids the infelicitous "yoo-hoo" sound.

Dick Margulis said,

April 9, 2017 @ 12:15 pm

I have no recollection of the who-for-people "rule" from my school days (1950s and 60s), but apparently it was a popular thing to teach in the 1970s and later. So it seems fairly recent.

Regarding the MWDEU note, though, it may be that we don't often hear "who" in reference to inanimate objects, but it seems perfectly normal to use "whose" in that context ("the book whose pages are square" rather than the more stilted "the book the pages of which are square," for example).

Levantine said,

April 9, 2017 @ 12:16 pm

More alarming than Bruni's own piece are the comments written in response to it by NYT readers. I had no idea that "that" for "who" was even an issue, let alone one that stirred such anger. Given the NYT's literary pretensions, you'd think its writers and readers would know their canon well enough to be at peace with such a venerable usage.

[(myl) The comments are definitely striking. Reading them, I wondered whether they came from the self-selected group that agrees with Bruni, with few others taking the time to weigh in, or whether we're watching prejudice formation in action, with those who are inclined to linguistic peeving seeing a chance to get in with the in-crowd (while also beating up on Trump, politicians, and modern life in general).]

Breffni said,

April 9, 2017 @ 12:21 pm

Does anyone else find the MWDEU example odd? – "We seek a managing editor that can…". I'd much prefer who in this case, though I can't put my finger on why. All the other examples in the post involve "men", "women" or "people", so maybe it's something about the weight of "managing editor".

[(myl) I agree with your preference, and I'm equally uncertain about the reasons. A quick web search suggest that who is generally chosen in the frame "We seek an X who/that" — one possibility is that the relative clauses in such cases are somehow semi-non-restrictive (or "supplementary", as Geoff Pullum would have it):

We seek an individual who has: B.Eng. or MSc Civil or Structural Engineering qualification with significant work experience

We seek an individual who has: Civil Engineering Degree or a Masters of Engineering/Science Degree; Significant and relevant research work

We seek an applicant who may be fresh out of secondary college or university with an interest in forging a long term career.

We seek an inspiring, dynamic leader who will take our Modern Foreign Languages Department to the next level through innovative practice

We seek an outstanding student who is an experienced embedded system firmware and control software developer with background in Computer or Electrical Engineering for our VOTERS project.

We seek an ordained minister who can fulfil the requirements of the job

description, and who has the following skills:

This seems to be connected with Joyce Melton's observation (above) that the use of who seem to make the relative clause more salient.]

Mark Meckes said,

April 9, 2017 @ 1:25 pm

Your own tone seems somewhat apocalyptic, with all this talk of zombie rules and relative clauses with human heads.

[(myl) Not to speak of the headless relatives!

I note, by the way, that headless relatives with that seem questionable:

"Who steals my purse steals trash."

"*That steals my purse steals trash."

]

Breffni said,

April 9, 2017 @ 1:56 pm

myl: Some evidence regarding restrictive vs non-restrictive (I'm trying to set up a context where the relative is unambiguously restrictive):

(1) [Two guys walk into a bar. One of them's wearing a hat.] The guy that's wearing a hat says…

(2) [Two managing editors walk into a bar. One of them's wearing a hat.] ?The managing editor that's wearing a hat says…"

Hmm. (2) sounded terrible to me initially, but I'm getting used to it. It's a fragile intuition. But perhaps that fragility derives from the fragility of the restrictive/non-restrictive distinction which (that?) you pointed out before.

RP said,

April 9, 2017 @ 2:45 pm

@Dick Margulis,

I agree that it is perfectly normal to use "whose" of inanimates, although there do exist peevers who object to it ("some sticklers", according to http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/grammar/whose-for-inanimate-objects?page=1 !).

Re "who" for inanimates – colloquially in BrE it is quite common to say "the organisation/company/party/government who …". I am not sure that it is common in formal usage. I also suspect this collective "who" might be less widespread in AmE, in the same way that plural verb agreement for collectives is less widely accepted in AmE.

Joseph C. Fineman said,

April 9, 2017 @ 7:52 pm

FWIW, Fowler says in MEU (1927), s.v. which)(that)(who: "(A) of _which_ & _that_, _which_ is appropriate to non-defining & _that_ to defining clauses; (B) of _which_ & _who_, _which_ belongs to things, & _who_ to persons; (C) of _who_ & _that_, _who_ suits particular persons, & _that_ generic persons. As examples of (C) he gives "_You who are a walking dictionary_, but _He is a man that is never at a loss_.

He vigorously defended inanimate "whose".

Mark Meckes said,

April 9, 2017 @ 8:51 pm

headless relatives with that seem questionable

In a closely related vein, relative clauses with personal pronoun antecedents and that seem questionable to me. "He who …" sounds fine, "he that …" sounds less off.

Phil Hand said,

April 9, 2017 @ 11:45 pm

WRT the managing editor example: One possible explanation for why who seems a bit preferable in that sentence might be the following. There are two ways to understand the term "managing editor": the role itself, and the person in the role. As a matter of contrast, I find "that" to be more thing-y, and "who" to be more person-y; an ad like this is going to go on to talk about the qualities of the candidates, not of the role; so if I were choosing between who and that in this sentence, I'd choose the more person-y one. This is all very marginal, not a rule at all, but I feel like that's what motivates an intuition which I share with at least some of you.

Michael Watts said,

April 10, 2017 @ 1:06 am

I note, by the way, that headless relatives with that seem questionable:

"Who steals my purse steals trash."

"*That steals my purse steals trash."

I don't think headless relatives with who or which are permitted either (headless relatives with what are going strong). I would have to say "Whoever steals my purse steals trash."

LL has posted on this exact question before.

boynamedsue said,

April 10, 2017 @ 2:22 am

Just to be pernickety, the Edgar Rice Burroughs example is not an example of Bruni's bugbear.

"The Moors were essentially a tolerant, broad-minded, liberal race of agriculturists, artisans and merchants—the very type of people that has made possible such civilization as we find today in America and Europe—while the Spaniards—"

I read this singular "people" as a synonym of "race", and so acceptable to the peevish. Collective entities composed of individuals are surely ok to use that. After all, I don't think it could possibly be argued that something like "It is a team that dates back to the 19th century" was wrong?

However, if this "rule" gained wider acceptance, like the unfortunate less/fewer thing has, perhaps we would witness a generalisation to contexts where entities composed of individuals could no longer take that due to, er, "logic"?

KevinM said,

April 10, 2017 @ 9:13 am

In both the Biblical and managing editor examples, the sense is that there's only one individual who fits the bill. In the first, that's the literal sense; in the second, probably more of a flattering fiction re: the "ideal candidate." Ms. Melton has put her finger on something.

Margalit said,

April 10, 2017 @ 10:05 am

I think that in the Jane Austen example, Catherine was surprised by the two carriages with the three people and not the three people.

BZ said,

April 10, 2017 @ 11:22 am

For what it's worth, "people that" and similar sounds completely wrong to me with the possible exception of the example that start with "one of". I don't know why that makes a difference to me.

John Buridan said,

April 10, 2017 @ 7:28 pm

I agree that Bruni brings nothing to the table and is impervious to facts.

However, it would be distracting to read an author who flip flops back and forth between using that and who whenever the choice is available.

A good rule of style is to make a choice and stick to it. Although 'that' in reference to people is not wrong, one should choose a convention and stick to it. Personally, I find the who/that distinction clung to by my old professor in college and other prescriptivists like Strunk & White, as good a suggestion as any. But beyond that, it's simply a suggestion.

What would be interesting is to know what suggestions other people would give to writers, especially young writers, who want guidance on making word choices in their composition.

*this post written, edited, and submitted with certified Elite White People English*

Levantine said,

April 10, 2017 @ 10:27 pm

John Buridan, can you point to a piece of writing that actually flipflops between the two options? I imagine that in most cases where both occur, euphony and context determine the choice, and the two can quite happily coexist without troubling the reader.

Jonathan Smith said,

April 11, 2017 @ 1:05 am

"A good rule of style is to make a choice and stick to it."

No, I'm pretty sure that's the definition of a zombie rule of style.

Jonathan said,

April 11, 2017 @ 3:31 am

Them that's got shall get

Them that's not shall lose

Andrew Usher said,

April 11, 2017 @ 5:17 am

Jonathan Smith:

Any style rule, of any sort, good or bad, stupid or prudent, is an example of 'make a choice and stick to it'. If you use that argument, you must be against all style rules, self-imposed or compelled.

This one is one of the zombie-est of zombie rules, I admit. I abhor it; and personally, I prefer the alternative rule of drawing a that/who(m) distinction parallel to that/which, which I observe pretty consistently – I don't even like 'that which' and sometimes use 'that that' – if German doesn't mind the repetition, why should English?

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Andrew Usher said,

April 11, 2017 @ 5:19 am

Also, 'who steals my purse steals trash' sounds grammatical to me, but that's clearly not an ordinary relative since the inanimate equivalent has to be the interrogative 'what' rather than the relative 'which'.

speedwell said,

April 11, 2017 @ 3:16 pm

Just as a kind of cheeky game, I went through every one of the above examples in my mind and changed each one (except for the poetry) slightly, replacing "who", "which", or "that" with something else. I avoid them in my own writing, so I don't find it difficult to do. For example, "There's only one person who/that qualifies" is not hard to change to, "Only one of these people qualifies", or, "We need a leader who/that has the ability to motivate" is just as good when stated, ""We need a leader with the ability to motivate", and even better when changed to, "We need a motivational leader".

Roger Lustig said,

April 11, 2017 @ 3:57 pm

@Jonathan: I look for song lyrics too, when this sort of thing comes up. First one that came to mind: "The girl that I marry." That led me to other lyrics, and I had to go and look up the X in the Beatles' "…all about the girl [X] came to stay…" (which turns out to be "who").

Joyce Melton said,

April 12, 2017 @ 12:33 am

Who brings a headless relative to a family reunion?

Aristotle Pagaltzis said,

April 15, 2017 @ 8:30 am

Right. A committed peever is not merely someone who claims that the language shall be used this way or that; s/he is proclaiming that s/he is the kind of person who uses English in that particular way, due to the fact that s/he is the kind of person who (in this example) refuses to regard people as objects – unlike people who use the language differently (here, politicians).

Having declared allegiance to a particular value system they have identified as associated it with a particular usage of English, they cannot then very well let facts get in the way of their proclamations.

So if there is any chance in decapitating zombie rules, it is probably possible only by taking this into account, and granting the peever their identity politics while disconnecting the link to usage. So for example here, that would mean agreeing that indeed, there are many who think of people as objects – but: their basic usage of the language is not where that attitude is to be found.

Are the means palatable for the given end? Your call…