Chinese restaurant shorthand, part 2

« previous post | next post »

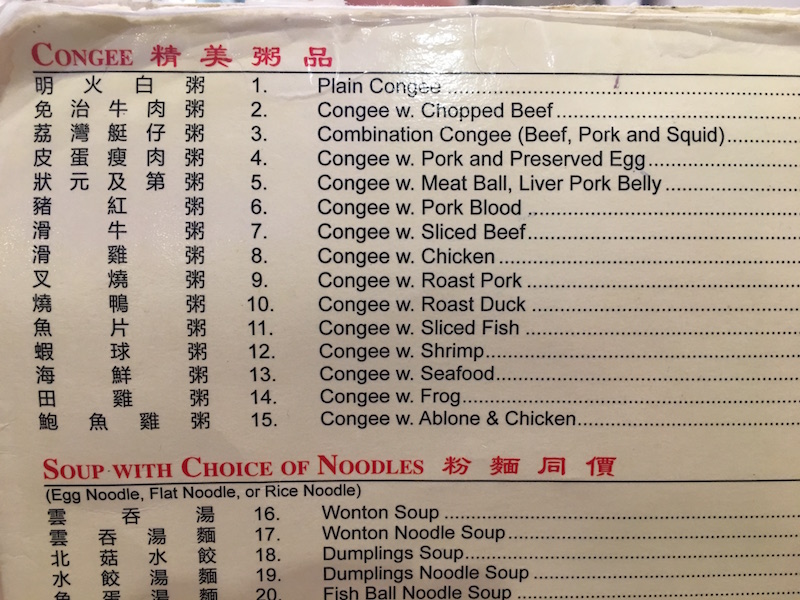

On Saturday the 26th, Yixue Yang and I went to the Ting Wong Restaurant in Philadelphia's Chinatown. I took one look at the menu and knew right away that the first thing I wanted was the second item on the menu, the Congee with Chopped Beef.

I love Hong Kong style congee (rice porridge or gruel). Long before I started to learn any Cantonese, I already had a fun mnemonic for how to pronounce zhōu 粥 ("congee") in that language. I would just think of the phrase sik6zuk1 食粥 ("eat congee"), which sounded a bit like "sick joke" to me, although, of course, it was divine to the taste.

The English designation of the second item on the menu, "with chopped beef", didn't seem quite right, but I knew from the look of the restaurant and the bowls of congee on the neighboring tables that it would be delicious.

If the English name sounded a bit odd, the Chinese name was even stranger:

Cant. min5zi6 ngau4juk6 zuk1 / MSM miǎnzhì niúròu zhōu 免治牛肉粥

The last three characters presented no problem; they just meant "beef congee". But the first two characters had us stumped:

min5 / miǎn 免 ("avoid; dismiss; escape; exempt; spare; excuse from; evade")

zi6 /zhì 治 ("control; cure; govern; manage; punish; rule; govern; regulate; administer")

We couldn't make any sense of "avoid control", etc. in the context of congee types. So we asked the waiters what it really meant. They just kept repeating "min5zi6", "min5zi6", as though we ought to understand that.

I should interject here that the waiters spoke very little English and not much Mandarin, so we were relying on their limited Mandarin and our limited Cantonese to try to understand their answers and explanations.

When the bowl of congee appeared before us and we saw what it looked like, we immediately grasped what the waiters were saying: "min5zi6" is the transcription of English "minced", and that is exactly how the beef in the bowl had been prepared.

Ting Wong specializes in what is known as caa1siu1laap6 / chāshāolà 叉燒臘, which are essentially barbecued meats.

caa1 / chā 叉 refers to the spit on which the duck is roasted

siu1 / shāo 燒 means "roast; bake; grill; barbecue"

laap6 / là 臘 signifies a special type of preserved meat traditionally prepared at the end of the year

So we ordered a ping3pun2 / pīnpán 拼盤 ("platter") of various cuts of roast duck, chicken, and the special prepared meat.

After we finished the meal, I used proper Cantonese to ask for the bill: maai4daan1 埋單 (that does not mean "bury the bill"!). See "Sound rules " (9/8/15), in the middle of the post.

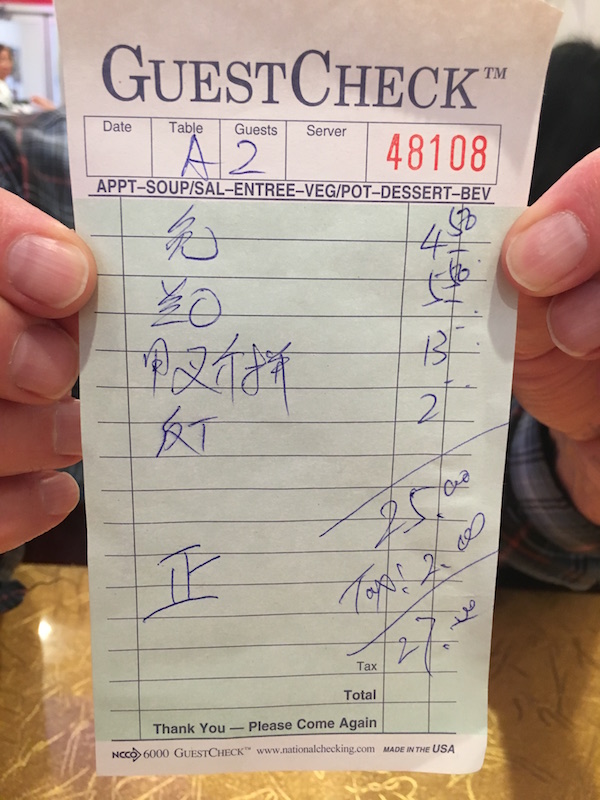

We may compare this check with another bill from the same restaurant when Yixue went there a couple of months ago: "Chinese restaurant shorthand" (9/22/16).

All right, let's go through the items on the bill for the meal on 11/26/16:

min5 / miǎn 免 — that's for the congee with minced beef

laan2 / lán 兰O — stands for gaai3laan2 / jièlán 芥兰O ("Chinese kale / broccoli / gai lan / kai lan order")

gaap3 caa1 gaai3 ping3 / jiǎ chā jiè pīn 甲叉介拼 — this one is rather complicated, but surprisingly we more or less figured it out on our own:

甲 ("armor; 'A' [as in 'A, B, C' — it's the first of the ten celestial stems]"), but here it's being used to indicate the phonophore of aap3 / yā 鴨 ("duck")

叉 as defined above, this is caa1 / chā 叉 and refers to the spit on which the duck is roasted

介 normally this is pronounced gaai3 / jiè and means "(lie / situate) between; introduce"), but here it is being used as a near homophone of gai1 / jī 雞 ("chicken")

拼 ("join / piece / place together", as in pīnyīn 拼音 ["putting / placing sounds together", i.e., "spell"], but here it's the different types of meat that are being "placed / put together" on a platter)

faan2 / fǎn 反T ("anti-; counter-; rebel; turn over" T) here stands for faan6 / fàn 饭T ("rice" T)

Now we have to tackle the hardest parts of the receipt, the "O" and the "T". This will take a considerable amount of unpacking. Yixue and I asked the waiter what "T" meant, and he used one of the two English words he spoke the whole time: "two". All right, we thought, "T" stands for "two", since we had two bowls of rice. We then again asked what "O" meant, since we had earlier been told that it means "order", but we didn't think that made any sense, since all of the items on the receipt were "orders". In contrast with "T" for "two" bowls of rice, we theorized that "O" must mean "one" order of gai lan, which is indeed what we got. But all of the waiters insisted the "O" stands for "order", so we just had to accept that. After all, it's their language, not ours!

But then we thought that we were probably wrong about "T" standing for "two", even though that's what the waiters told us several times: "T" means "two" (the only other English word beside "order" they spoke to us). So we again confirmed that "O" means "order", not "one", as we had hypothesized. We then again asked for confirmation that "T" really means the English word "two", and were told that it does not stand for the English word "two". Rather, it is the second stroke of the character / zhèng 正 ("orthodox; correct; right; main", etc.), as one of the waiters demonstrated at the bottom left of the bill. This use of 正 to mark off groups of five fills the same function as our use of four vertical strokes crossed by a slanting line to complete a group of five. See the section on "Clustering" in the Wikpedia article on "Tally marks". Yixue tells me that she and her co-workers in the Chinese section of Penn's library use the technique of counting by marking off 正s to keep track of how many books they bar code each day in the library.

That completes today's exposition of Chinese restaurant shorthand.

And here, just to make you drool, is a photograph of the glass case at the front of the Ting Wong Restaurant:

Ryan said,

December 1, 2016 @ 1:30 am

The word "congee" will always be weird to me since, having grown up in a Cantonese household, I had always referred to it as zuk1 (or "jook", if I had to write it). It wasn't until I was a teenager that I first encountered the word "congee" and I thought it was Engrish for "congealed".

Simon P said,

December 1, 2016 @ 2:34 am

My poor Swedish palate could never take the culinary marvel that is Cantonese congee. I find it impossible to stomach. Cha siu, on the other hand, is absolutely divine.

Very interesting post on restaurant shorthand! I'm impressed you managed to decrypt all those signs with so little help. And the 正 tally system was, I believe something I'd read about somewhere and since forgotten. It's very clever!

flow said,

December 1, 2016 @ 4:12 am

But why? Why would the second stroke of 正 become 〇, and what is that supposed to mean? As I know the tally system, you write 一 … 丅 … 下 … until 正 is complete. 反丅 is understandable; bowls of rice are often ordered extra, so the 丅 is just a 'open counting' mark that can be added to as the case may be. But 〇?

Jens Ørding Hansen said,

December 1, 2016 @ 4:19 am

The first few times I bought fresh meat at a street market in Hong Kong (Wan Chai) in 1997, I was too dumb to understand what the butcher meant when he asked me if I wanted the beef "min5zi6". It was not a word I could relate to any of the Cantonese I had learned. Around the third time or so I suddenly realized it was simply a loan word from English.

Cervantes said,

December 1, 2016 @ 9:38 am

"Congee" (or sometimes "conjee") is an ancient word the English borrowed from Tamil (கஞ்சி), perhaps via the Portuguese who preceded them in India.

Doc Rock said,

December 1, 2016 @ 11:27 am

My first wife, a Taiwanese from Tainan, loved congee [ jūk/粥 ] with 'beef wool" [rousong/肉鬆]. Back in the 1960's it [肉鬆] was nearly impossible to find except in Chinatown in NY so her father who had a canning factory in Tainan sent her a couple of cans of "pineapple" that were actually full of the 肉鬆.

Doc Rock said,

December 1, 2016 @ 12:16 pm

In response to Jens Ørding Hansen's comment, I'd add that in Korean, Japanese, and Mandarin, I often found that the greatest difficulties were in processing English loan words and children's speech.

Doc Rock said,

December 1, 2016 @ 12:20 pm

Tamil கஞ்சி is read 'kañci', I found.

SO said,

December 1, 2016 @ 12:38 pm

<< "min5zi6" is the transcription of English "minced"

Reminds me of Japanese menchi ~ minchi < mince(meat). Any chances that min5zi6 was inspired by this rather than the original English?

JR said,

December 1, 2016 @ 2:29 pm

Which leaves the question of where the English term "congee" comes from. This is a weird tree that Etymonline is sending me barking up: http://etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=congee

JR said,

December 1, 2016 @ 2:31 pm

M-W says it's from Tamil. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/congee

David Scott Marley said,

December 1, 2016 @ 3:20 pm

Congee from the French congé is part of the vocabulary of nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century upper-class etiquette. It's a different word from congee the food, and you're not likely to encounter it unless you're a reader of Victorian novels and/or old etiquette books. Etymonline and the Collegiate are each giving only one of the two words, and not the same one. The Chambers Dictionary and the Shorter Oxford both give both words.

Tim said,

December 1, 2016 @ 6:01 pm

I'm not surprised to see the Cantonese name for congee is similar to Thai โจ๊ก (pronounced somewhere between joek or chok to my ears) because my Thai in-laws refer to it in English as "Chinese breakfast". According to Wikipedia it's a Southern Min loanword.

I am surprised to see the similarity between the Cantonese and Thai for chicken, ไก่ (gai). ไก่ is a pretty basic word in Thai; I wouldn't guess it's recent loanword and I didn't think they were from the same language family. Is there an early relationship between the two languages that would explain the overlap?

Eidolon said,

December 1, 2016 @ 8:20 pm

"I am surprised to see the similarity between the Cantonese and Thai for chicken, ไก่ (gai). ไก่ is a pretty basic word in Thai; I wouldn't guess it's recent loanword and I didn't think they were from the same language family. Is there an early relationship between the two languages that would explain the overlap?"

Schuessler believes it is an onomatopoetic area word shared by Sinitic, Tai-Kradai, and most other language families in the region. Norman by contrast thinks it is a loan from one of the Southeast Asian languages into Sinitic. Your guess is as valid as anyone's. The proto-Sino-Tibetan form, k-rak or k-ak, however, is obviously onomatopoetic.

Chris Kern said,

December 1, 2016 @ 10:11 pm

I also find "congee" a strange term, because I only associate 粥 with Japanese "okayu". I usually refer to it as rice porridge in English.

Doc Rock said,

December 1, 2016 @ 10:31 pm

Of course [o] -kayu お +かゆ 「粥」 aka おもゆ [重湯]

Chas Belov said,

December 2, 2016 @ 1:18 am

I was surprised to see 介 used to mean "chicken." As I've noted before, my regular Chinese restaurant uses 介 to mean "broccoli" (for "gailan"). I haven't ordered chicken there in some time but if memory serves, they use 鸡.

Some of our staff at my office play ping pong at lunch and use 正 to keep score.

And for the record, I love jook.

Jens Ørding Hansen said,

December 2, 2016 @ 6:13 am

@Chas Belov: Agree. "Gaai3" sounds almost nothing like "gai1". I'm not an expert at restaurant shorthand, but it seems very odd to use 介 to represent 雞. Using 介 to represent 芥蘭 (gaai3laan2) would of course be quite natural.

Fluxor said,

December 2, 2016 @ 3:23 pm

lán 兰O — stands for gaai3laan2 / jièlán 芥兰O ("Chinese kale / broccoli / gai lan / kai lan order")

Did the veggies come drizzled with a bit of dark, thick oyster sauce as it is typically served? If so, the "O" probably stands for "oyster sauce". Given the waiter's limited English, did he really say "order" or "oyster"? I wonder…

"Ting Wong specializes in what is known as caa1siu1laap6 / chāshāolà 叉燒臘, which are essentially barbecued meats."

Theses types of Cantonese/Hong-Kong style restaurants typically serve foods commonly called 燒臘 (without the 叉), as 燒臘 is a contraction of 燒味 (BBQ) and 臘味 (preserved meats).

燒味 (BBQ) consists of any number of meats, such as 叉燒 (BBQ pork shoulder), 燒鴨 (roast duck), 燒鵝 (roast goose), 燒肉 (roast pig, then cut into chunks that includes the crispy skin, fat layer in the middle, and a bit of meat at the bottom), etc. 臘味 (preserved meats) consists of sausages, duck, chicken, etc. that are preserved by marinating in salt/sauces then air dried.

These restaurants also typically advertise 粥粉麵飯 (congee, vermicelli, noodles, rice) on their banner or sometimes just 粉麵 (vermicelli, noodles) as rice is pretty much a given at Chinese restaurants.

Daniel Barkalow said,

December 2, 2016 @ 6:08 pm

Maybe "兰O" is when you just order kale, and "兰" would be their default meat with kale? If they write "min" for "(congee with) min(ced beef)", it seems plausible that something more popular and common is called "kale", and they use an "O" to mean that the "kale" you want isn't a shorthand.

Victor Mair said,

December 2, 2016 @ 8:30 pm

lán 兰O

We asked three waiters and the laoban ("boss"), and they all said that "O" means "order".

David Marjanović said,

December 3, 2016 @ 1:46 pm

Ooh, like the line under an Egyptian hieroglyph that indicates it's used for a word and not for a consonant…

No, the first and the second stroke became 丅 as far as I understand.

julie lee said,

December 3, 2016 @ 11:52 pm

I don't think kale is ever served in a Chinese restaurant Nor is collard greens or chard.

Growing up in China, Hongkong, and Taiwan, I don't remember ever eating kale, collard greens or chard, all dark leafy greens that are always seen in American supermarkets now (at least here in California).