Sinographically transcribed English

« previous post | next post »

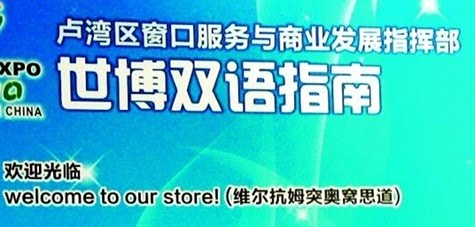

We have seen, over and over again, that the rapid spread of English in China causes consternation among language authorities there, most recently leading to the ban of English in the media. Here's one way to deal with this problem, at least in terms of superficial appearance:

[Click to see the rest of the sign.]

What we see is a sign that was posted at the Shanghai Expo. The title at the top is "World Expo Bilingual Guide" (Shìbó shuāngyǔ zhǐnán 世博雙語 指南). I'll transcribe a few of the listed expressions to show how the guide works:

Huānyíng guānglín 歡迎光臨

welcome to our store!

Wéi ěr kàng mǔ tū ào wō sī dào 維爾抗姆突奧窩思道

Zǎoshang hǎo 早上好

Good morning!

Gǔ de māo níng 古的貓寕

Duìbùqǐ, wǒ zhǐ néng jiǎng jiǎndān de yīngyǔ 對不起,我只能講簡單的英語

I'm sorry, I can only speak a little English.

Ǎn sāo ruì, āi kǎn wēng lèi sī bí kē é lèi tōu yīng gé lìshǐ 俺搔瑞,挨 坎翁累絲鼻科額累偷英格歷史

Zàijiàn 再見

Bye Bye!

Báibái 白白

If one attempts to make "sense" of the Chinese character transcriptions of the English expressions, one will find that most of them are complete gibberish, although occasionally they convey a bit of irrelevant meaning. For example, in the third example cited above, the transcription of "English" — yīng gé lìshǐ 英格歷史 — might be thought of as meaning "English style history," and the Báibái 白白 of the last example looks as though it means "white white."

The second example is more interesting. Gǔ de māo níng 古的貓寕 superficially appears to imply "old cat serenity," but that is merely unwanted interference from the semantically heavy characters, which are being used here (or, rather, should be used here) purely for phonetic purposes.

My father-in-law, a Shandongese from near Qingdao, learned how to say "Good morning" by writing it neatly in his notebook as Gǒutóu māo níng 狗頭貓嚀, which he explained to me as meaning "dog's head cat's meow" (though the níng 嚀 doesn't really mean "meow").

Anyway, you get the picture of how this method works. There seems to be a presumption on the part of those who advocate this method of annotating English that the use of Chinese characters somehow "tames" the foreign tongue. Never mind that Hanyu Pinyin is the official romanization of the People's Republic of China, the means through which all Chinese children begin to learn to read and write. And never mind that all Chinese children learn English, starting from kindergarten or at least first grade. So it's not as though the Chinese population is unfamiliar with the Roman alphabet. Still, writing out the sounds of English in Chinese characters apparently gives an assurance of domestication to the Sinographic realm. Consequently, despite the erasure of word boundaries and the poor phonological representation, some folks would prefer to write English this way than let English speak for itself.

Of course, this is one way to guarantee the adaptation of English words to Mandarin phonological norms, as normally happens with borrowed words and phrases, with foreign proper names, and so on. However, the context here is a pronunciation guide for a short English phrase book — and the overlay of logographic pseudo-meaning risks other sorts of misunderstanding.

[A tip of the hat to Kira Simon-Kennedy and Oliver Radtke]

~flow said,

December 26, 2010 @ 2:55 pm

it would appear that the authors in some cases even tried to *avoid* meaningful characters where they would have been appropriate: 'baibai' is very common (at least in taiwan), is always written as 拜拜, and as close to 'bye-bye' as possible. still, the writers eschew these characters, preferring to render the sound with 白白. maybe they did that so as to avoid the impression that the characters were chosen for their meaning.

another note: i immediately understood 英格歷史 as 'english history', since 英格蘭 is the 'long' version of 'england' (which is more often referred to as simply 英國).

Twitter Trackbacks for Sinographically transcribed English: We have seen, over and over again, that the rapid spread of English i... [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

December 26, 2010 @ 3:01 pm

[…] Sinographically transcribed English: We have seen, over and over again, that the rapid spread of Eng… languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2864 – view page – cached […]

John Cowan said,

December 26, 2010 @ 3:10 pm

Well, we've talked about Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (aka Cordwainer Smith) and his ài zé rén dé 'love/duty/humanity/virtue' or 'I surrender' a time or two here on the Log. The intertubes' current best guess is that the pamphlet (dropped on Chinese troops during the Korean War) actually said 爱责仁德 or perhaps 爱孝仁德; how would you reconstruct it? It doesn't have to be a real tetragram, but it does have to be fairly readable by ordinary Chinese soldiers in the 1950s.

Glossy said,

December 26, 2010 @ 3:55 pm

Like everyone who loves languages and linguistics, I would much prefer a future in which there is a diversity of strong, self-confident languages to a future in which English gradually devours everything else. In that sense I applaud any Chinese resistance to mindless borrowing.

On a lighter note this post reminded me of the Russian phrase "Cанька бери мяч", which sounds as close to "thank you very much" as anything in Russian can, while actually meaning "Alex, take the ball."

Henning Makholm said,

December 26, 2010 @ 5:33 pm

Even if the glyphs of the Roman alphabet themselves are the same, are their values in Pinyin close enough to English orthography that familiarity with the former will actually help one pronounce English?

(Not that I'm sure I get the point of such phrasebooks in the first place. If someone needs a phonetic transcription to say "I can only speak a little English", chances are that even that is an exaggeration, and such a person has no chance of parsing and understanding an unprepared-for English sentence uttered by a tourist, with or without the help of a phrasebook. It would be more honest useful to learn to say "I can't speak English at all", paradoxical though that might sound at first).

the other Mark P said,

December 26, 2010 @ 9:06 pm

Like everyone who loves languages and linguistics, I would much prefer a future in which there is a diversity of strong, self-confident languages to a future in which English gradually devours everything else. In that sense I applaud any Chinese resistance to mindless borrowing.

No need to worry then, as the borrowing is not "mindless".

If life is easier for Chinese people to add English words directly, why do you want to stop them? Aesthetic reasons about "diversity of language" don't feed people or get them jobs. Nice for you, a rich English speaker, to get all sniffy about others wanting the same breaks.

Or do you want all the Chinese to stop wearing jeans and t-shirts and get back to "proper" traditional clothes too?

Albatross said,

December 26, 2010 @ 9:55 pm

If life is easier for Chinese people to add English words directly, why do you want to stop them?

I agree. English speakers have been adding foreign words to their language for some time now, and that practice has never been denounced that I've heard. In fact, it's generally a good thing. That's why we have "salsa" instead of "spicy red stuff that's not ketchup".

Why not let the Chinese speakers do the same and add to their language as benefits them, and then let us not worry about it?

Mr. Fnortner said,

December 26, 2010 @ 10:14 pm

The Japanese go to some pains to transliterate English loan words into katakana for ease of recognition as foreign words in writing. They could just as easily use hiragana characters, but reserve that syllabary for native words. It's a technique that might prove useful to the Chinese if they but had such a script.

DN said,

December 26, 2010 @ 10:26 pm

That's why we have "salsa" instead of "spicy red stuff that's not ketchup".

Don't you mean "spicy red stuff that's not that other spicy red stuff"?

Glossy said,

December 26, 2010 @ 10:39 pm

"English speakers have been adding foreign words to their language for some time now, and that practice has never been denounced that I've heard."

Besides the diversity argument that I've already made above, there is another one. Since a lot of abstract English vocabulary was borrowed from Greek, Latin and French, much of it is etymologically obscure to most English speakers.

Example: if you didn't pay attention in biology class and then see the word erythrocyte in print as an adult, you won't be able to guess what it means. Not so in Chinese, where erythrocyte is 紅血球 (literally "red blood ball"). Diabetes is 糖尿病 (sweet urine disease), etc. Everything is transparent, even highly technical terminology. A person without too much education doesn't feel like a fool as often as he otherwise would.

A couple of days ago I learned a new for me word – hormesis. I had to treat it like a black box because its contents are not guessable from its outer appearance even if one knows a bit of Greek. Well, that problem isn't universal. In some languages, like Chinese, obscure terminology is normally etymologically transparent. Makes life easier, doesn't it?

I'm surprised that you've never heard of this argument before. Believe me, I did not invent it.

Bob Violence said,

December 26, 2010 @ 11:05 pm

Like everyone who loves languages and linguistics, I would much prefer a future in which there is a diversity of strong, self-confident languages to a future in which English gradually devours everything else.

Chinese language regulators are the last people on earth concerned about "a diversity of strong, self-confident languages".

J. Goard said,

December 26, 2010 @ 11:42 pm

@Glossy:

I'm surprised that you've never heard of this argument before. Believe me, I did not invent it.

What exactly is your argument?

As a student of Korean, I certainly agree with your claims in the last post. But, really, are those the terms in danger of being replaced by English loanwords? "Diabetes"? Even in English, one could reasonably view our Greco-latinate technical vocabulary as a historical accident. I don't see it holding true today as a principle of lexical replacement. (Does anybody think "earache" is going to give way to "otalgia" any time soon?)

Now, I guess I could make a pretty good argument that foreign medical students (who are generally well ahead of the curve in English) are wasting a lot of their extremely precious time learning Greek and Latin, which could be avoided if the English-speaking medical profession adopted plain English names. Is that what you're getting at?

Yao Ziyuan said,

December 26, 2010 @ 11:42 pm

嚀 (simp. 咛) in Modern Chinese serves and only serves as part of the word 叮咛 which means "to remind". So if a cat is "reminding" you something, it is "speaking", which is, meowing.

Glossy said,

December 27, 2010 @ 12:10 am

Albatross said:

"English speakers have been adding foreign words to their language for some time now, and that practice has never been denounced that I've heard."

Well, I HAVE heard the practice of mindless borrowing denounced, and on perfectly sensible grounds. I gave an example. The confusion which many modern English speakers experience in regards to specialized vocabulary to a large extent goes back to mindless borrowing in centuries past. If English came up with native calques or coinages then, there would have been less confusion now. German is a bit better at this. I don't expect English to change now, but I'll certainly root for Chinese not falling into the same trap.

Carl said,

December 27, 2010 @ 12:25 am

In Japanese, it's trendy to use opaque English medical terms instead of transparent Sino-Japanese terms.

Matt said,

December 27, 2010 @ 12:34 am

There seems to be a presumption on the part of those who advocate this method of annotating English that the use of Chinese characters somehow "tames" the foreign tongue. Never mind that Hanyu Pinyin is the official romanization of the People's Republic of China, the means through which all Chinese children begin to learn to read and write. And never mind that all Chinese children learn English, starting from kindergarten or at least first grade. So it's not as though the Chinese population is unfamiliar with the Roman alphabet. Still, writing out the sounds of English in Chinese characters apparently gives an assurance of domestication to the Sinographic realm. Consequently, despite the erasure of word boundaries and the poor phonological representation, some folks would prefer to write English this way than let English speak for itself.

I can think of one good, logical reason why Chinese folks might prefer English words written this way: because it gives them a fighting chance at pronouncing the damn things. (Pace all those Chinese kids learning English from the first grade; given that someone thinks that these pronunciation guides are necessary, I assume that there are still a lot of kids to whom it doesn't stick and a lot of adults who either never had that opportunity or forgot whatever they learned through long periods of disuse.)

In Japan, too, most people over 60 are familiar with the Roman alphabet, but that doesn't help them pronounce new English words presented in it, much less sentences. Italian and Hawaiian, maybe; English, no. Katakana, on the other hand, can be pronounced by everyone.

Albatross said,

December 27, 2010 @ 12:36 am

Don't you mean "spicy red stuff that's not that other spicy red stuff"?

Exactly!

kktkkr said,

December 27, 2010 @ 3:59 am

Maybe that would explain why some Chinese speakers put stresses in weird places. For example, if they were following the sign I expect them to end up reading "Welcome to our store" as "WeiCommto arwa sTore!" (slightly exaggerated)

If the purpose is to make the pronunciation of English words clearer to Chinese speakers-and-readers, it's not very well executed: The example for "I can only speak a little English" contains many words that are excessively complicated (at least, to learners of Chinese), and some words with multiple pronunciations were used, e.g. "的" in "good morning".

Alex said,

December 27, 2010 @ 1:09 pm

This is just a simple question for Victor Mair: why did you choose to use traditional script in your post even though the sign is printed in simplified?

I'm currently learning Cantonese and I know the use of one script over another can be pretty political/ideological. Maybe you just happened to use traditional because you felt like it?

Randy Alexander said,

December 27, 2010 @ 1:30 pm

I wrote about the nature of this problem (and a potential solution), with audio examples (!) here (pt 1) and here (pt 2).

But the solution takes for granted that the Chinese reader of such a phrasebook will speak Standard Mandarin (otherwise you might get some surprising phonetic renderings), and of course not everybody does. Lots of people in China don't speak Mandarin at all.

It also only works for literate speakers. It's not so uncommon to find people over 50 who are illiterate. I live in Xiamen (which is very developed), and when I asked my landlady to write a receipt for my rent, she said she couldn't read or write; the best she could do was sign her name after I wrote the receipt.

Theodore said,

December 27, 2010 @ 4:58 pm

This transcription scheme is really no worse than transcriptions of Russian words to English spelling. Even though Russian Cyrillic orthography is nearly phonetic (except for the odd "-ого", etc.) and the Cyrillic alphabet should be as easy for an English speaker to learn as Hanyu Pinyin would be for a native Chinese speaker, we still have "spar-SEE-bo" in travelers' phrasebooks.

Extra points to the Russian who understands the American reading Russian transcriptions made by a Brit.

bryan said,

December 27, 2010 @ 6:28 pm

erythrocyte is 紅血球 (literally "red blood ball")

Even though 球 = ball in Chinese, meaning that it's round, that's correct because it's a Modern Chinese translation because "red blood cells" are round [but also sort of flat, too] if you look under the microscope.

Wrong in using the word erythrocyte! Latin supporters suck! Modern scientists who are Christians no doubt, created this word, yet they used an ancient Greek word, ερυθρό [erythró] for red? The modern Greek word for red = κόκκινο [kókkino]. The scientific community should change everything back to it's original Greek, and to update older terms to their Modern Greek equivalents, so it's "kokkinokyte" instead of "erythrocyte", which is incorrect and out of date. cell = κύτταρο [kýttaro] in Greek, so cyte should be corrected as "kyte". The English word cell is from Middle English via Old French via Middle Latin where the word means "room" in Latin. No where was I told in biology class that a cell is a room!

There's no letter c in ancient Greek or Modern Greek. It's from the Greek letter "final sigma" ς, so called because this form only occurs as the final consonant in a word. It is where the letter C / c in Latin was made from. Since sigma is the Greek letter for s, the Romans also used C/c for the s sound initially, that's why before e, or i, the letter c is an s sound in English.

Victor Mair said,

December 27, 2010 @ 7:29 pm

As Perry Link mentioned to me in a private communication, his favorite in this genre is the Chinese guy who wrote down the Japanese for "Good morning" (ohaiyo gozaimasu) as È hái yào gǒu zá yě mà sǐ 饿还要狗杂也骂死! The sounds are not too bad for conveying the Japanese pronunciation, but as soon as you read this string of characters, you feel that it means something, sort of like "[He / I was] hungry [so he / I] still wanted dog organs, moreover was thoroughly scolded" (lit. "scolded to death").

@Alex I usually use the traditional forms because I'm far more familiar with them than I am with the simplified forms, having studied the traditional forms for nearly half a century, and they're also much easier for me to type (my system is set up that way and I type traditional characters every day for my papers, teaching materials, etc.). Absolutely nothing political about it, so far as I am concerned. It's simply a matter of ease and convenience. If somebody replies to me in simplified characters because they feel more comfortable doing so, I don't mind in the slightest. I've answered this question before on Language Log. This may be the last time I do so.

William Page said,

December 28, 2010 @ 12:05 am

Comment on the two sets of characters offered for the English expression "bye-bye": I'd favor the character that means "white" over the one that means "worship." Why? Because the two rising tones come closer to the usual English intonation pattern for this expression than two falling tones. (Sorry, my computer doesn't do Chinese characters.)

Alex said,

December 28, 2010 @ 10:37 am

@ Victor:

Ah, I see. Also, I'm a fairly new reader. Excuse me

minus273 said,

December 29, 2010 @ 11:43 am

I can for my part assure that the practice is by no means limited to those with a certain authority. In the 90's (I don't know if it's the case now), on an English class in my hometown in Sichuan, everyone, despite the disencouragement of the teacher, noted the words in Chinese characters. A possible reason is that people educated in the 60-80s never get good in pinyin, anyway. Unlike in the present period, where the knowledge of pinyin and Standard Mandarin is reinforced by input methods, the Sichuan people, who, by the way, never speak Standard Mandarin well because of the interference of the local language (another Mandarin dialect, too close to be confortable), forget pinyin quickly in their adulthood as something that rarely prove useful.

Bruce Humes said,

December 30, 2010 @ 4:09 am

Interesting discussion, and glad to be able to take part in it without fear of censorship.

I also left a comment today at China Daily online, re: the article entitled "English Adopts more Chinese Phrases." (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/life/2010-12/29/content_11770459.htm)

I noted that English has indeed adopted many such words/phrases, and a good number of them are to be found in US, Australian or British dictionaries, implying that those phrases are acceptable currenency in thos societies. Whereas foreign words often used in speech and media in China are more unlikely to find themselves listed in dictionaries. And with the latest regulation discussed here, even less likely.

I ended my item with a reference to "Thought Police?"

And sure enough, my comment has been deleted…

Kevin Iga said,

December 30, 2010 @ 12:41 pm

This seems a lot like phrase books that do things like:

Hello: Guten Tag (GOOT-uhn TOGG)

The danger in omitting the third version is that an English speaker will try saying [gʌtn tæg] or something like that. The third version will not get you speaking it like a German but at least it's a lot closer than [gʌtn tæg].

Likewise, "Welcome to our store", if viewed as pinyin, might be pronounced as [wə t͡sʰo mə tʰo ou aɻ to ɻə], which I think is pretty hard to understand (wuh tsowma tow owe are tora?). Now it might be claimed that it's not much better to say Wéi ěr kàng mǔ tū ào wō sī dào (wearcongmu to owoh stao?), but it's probably the best one can do without teaching the person English with an audio track at least.

Besides, in English, we write "Kung fu", "Gung ho", "Taiwan", etc. and we don't use the Chinese characters. For that matter we borrowed words from Greek and no one insists that we write "polyglot" using Greek letters. Why worry about Chinese using or not using our writing system when explaining how to pronounce English phrases?

Haidong said,

December 31, 2010 @ 1:45 am

Don't take it too seriously. We Chinese don't learn English this way. I can hardly image that anyone could memorize these long sentences ( if they could be called as sentences) which absolutely make no sense in Chinese, for example: "俺搔瑞,挨坎翁累絲鼻科額累偷英格歷史"。

Actually I live in Luwan disctrict where the picture was taken. I am pretty much sure that this kind of nonsense was made by some idle bureaucrats who were eager to show to their boss that they made some contribution to EXPO. We ordinary people care nothing about it.