Rap scholarship, rap meter, and The Anthology of Mondegreens

« previous post | next post »

Paul Devlin has a fascinating series of articles at Slate on transcription errors in the recently-published Anthology of Rap. Well, the first one starts out as a review of the book, but after the first paragraph or so, it's all about the Mondegreens: "Fact-Check the Rhyme (The Anthology of Rap is rife with transcription errors. Why is it so hard to get rap lyrics right?)", 11/4/2010; "It Was Written (Why are there so many errors in The Anthology of Rap? The editors respond)", 11/10/2010; "Stakes Is High (Members of the Anthology of Rap's advisory board speak out about the book's errors. Plus: Grandmaster Caz lists the mistakes in his lyrics.)", 10/19/2010.

Some of the cited errors are more consequential than others:

1. At the 1:58 mark, the anthology transcription reads "against the very best." Caz told me it should be "we rock the very best."

2. At 2:03, the anthology has "And you'll be so impressed." Caz said it should be "And baby I want your address."

As Devlin admits,

Transcription of rap lyrics is excruciatingly difficult, due to speed of delivery, slang, purposeful mispronunciation, and the problem of the beat sometimes momentarily drowning out or obscuring the lyrics.

We can add the problem of background noise in live recordings, and the difficulty of decoding local or personal allusions. But there seem to be a lot of errors that are just careless, and Devlin points out several places where unlikely mis-hearings seem to have been copied from on-line collections of lyrics, contradicting the anthology editors' claims of a painstaking seven-step transcription methodology. One particularly egregious case:

Here is an example in which it seems like nobody bothered to even listen to the song, but instead must have relied on some incorrect transcript. On the 1979 song "Superrappin'," Melle Mel of the Furious Five does not say "1-2-3-4-5-6-7/ rap like hell make it sound like heaven/ 7-6-5-4-3-2-1 …" He says "one, 23, 45, 67/ rap it like hell make it sound like heaven/ seven, 65, 43, 21 …"

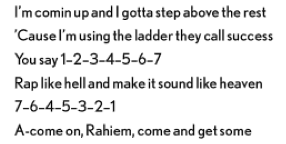

But ironically, Devlin himself is rather careless here, at least by the standards of scholarship that he (appropriately) would like to see The Anthology of Rap uphold. In the first place, he slightly misquotes TAR's transcription. Here's an image of the relevant part of p. 72, courtesy of amazon.com:

In his account of TAR's transcription, Devlin omits "You say" from the 1-2-3-4-5-6-7 line, and the "and" from the "Rap like hell (and) make it sound like heaven" line. He also leaves out an initial "fifty" in the second next-to-last line, which I transcribe (see and hear below) as "fifty-seven sixty-five forty-three twenty-one".

As for what Melle Mel really sang in the "hell and heaven line, it was this:

which (after listening carefully several times with headphones) I transcribe as

rappin' like hell to make it sound like heaven

There are a couple of plausible differences of opinion here. There's definitely a sung syllable between "rap" and "like", and another between "hell" and "heaven". TAR omits the first; Devlin omits the second. I hear the first one as the participial ending "-in" , while Devlin hears it as "it"; I hear the second one as "to", while TAR hears it as "and".

Devlin is absolutely right to excoriate TAR for its transcription of the number-sequence lines. Here's the first one:

I transcribe this as

((I)) say one twenty three forty five sixty seven

TAR's version is so completely wrong that Devlin wonders if they even bothered to listen, rather than just copying some website's version of the lyrics:

You say 1-2-3-4-5-6-7

I wonder whether this might have been botched by a copy editor, who saw something like "1 23 45 67" and figured it had been badly typed by the transcriber. Whatever the reason, it's a bad mistake. (On the other hand, Devlin didn't listen very carefully either, since he leaves out the initial "fifty" two lines later.)

Devlin notes that the editors promise to correct some of their errors in future editions.

While we're on the subject of possible improvements in future editions of The Anthology of Rap, I'd like to note that a critical aspect of these lyrics is systematically missing from the kind of transcripts that this anthology provides, no matter how textually accurate they might become. I'm talking about the relationship of the lyrics to the metrical background. This is implicit in the original recordings, of course — but so are the words themselves.

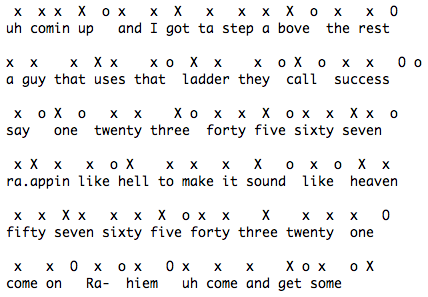

As an example, here's the whole passage whose TAR transcription is shown above:

Here's my transcription:

uh comin' up and I got ta step above the rest

((a guy that uses)) that ladder they call success

((I)) say one twenty-three forty-five sixty-seven

rappin' like hell to make it sound like heaven

((fifty-))seven sixty-five forty-three twenty-one

come on Rahiem uh come and get some

(There are lots of things I'm not sure about. For example, is the syllable before "comin' up" a version of "I" or "I'm", or (as I've transcribed it) just "uh"? This is a good reason, as Devlin suggests, to ask the authors for corrections while it's possible to do so.)

The basic rhythmic analysis of this piece is fairly easy, since its minimal time unit (of a bit more than 1/8 of a second) is pretty clear throughout, either in the rapping or in the musical background. (That doesn't guarantee that I made no mistakes in the analysis below — but it should make it relatively easy to correct errors — Breffni O'Rourke pointed out several in my original transcription — and settle most disagreements.)

These minimal units are grouped four to the beat — i.e. every fourth unit is nominally stronger — and there are typically four beats per line, both in the metrical background and in the lyrics. Generally, the stressed syllables in the lyrics align with the strong beats in the background meter, except in the last position in lines with masculine rhymes, where the last stressed syllable generally anticipates the musical beat by one minimal unit. However, sometimes (as in the last line of these three couplets) there is more extensive "syncopation". This line has only three strong syllables in the lyric, and the last of them is only one that aligns with a strong beat in the metrical background!

(As always in such cases, there's an interesting question whether this should be thought of as a superficial deviation from an underlyingly square rhythm, or rather as a different draw from a set of available polyrhythmic patterns. For some more discussion, see e.g. "Rock syncopation: Stress shifts or polyrhythms?", 11/26/2007. Note in any case that the mixture of four-beat and three-beat (lyric) lines evokes the traditional English ballad meter, whatever we're to make of the variations in alignment.)

In the metrical transcription below, I've used lower-case letters for off-beat minimal time elements, and upper-case letters for the time-points corresponding to the "beat", with X and x for time-points aligned with syllables in the lyric, and O and o for time-points without a corresponding syllable. The audio clip is repeated here for convenience:

This notation is somewhat clunky, and it would be easy to do better, say with some system of diacritics (for indicating the beat alignment of syllables) and interpolated symbols (for indicating beats without aligned syllables). But however we notate it, it seems to me that anyone who cares about rap or hiphop as poetry ought to be interested in its meter. The fact that European and American art poetry has largely been largely unmetered for the past century shouldn't prejudice the analysis of the genuinely sung lyrics of the same period, where the musical background and its relationship to the words is isomorphic to traditional notions of metrical structure in accentual-syllabic verse during the previous five centuries or so.

The metrics of hiphop and rap are particularly rich and interesting, in my opinion, and many scholarly books and papers will no doubt be written on this subject eventually. In retrospect, TAR's lack of any substantive discussion of rap meter will (I predict) seem even stranger than the scholarly carelessness of its transcriptions.

The first 30 or so comments on this post were mostly about nit-picky points of who-heard-what-where in the particular passage that I reproduced above. For a while, I tried to respond to questions, and to delete repetitive "me too" posts on various aspects of this debate — but the problem is, all of these comments are essentially beside the point, except for underlining the fact that transcription of rap lyrics has a subjective aspect.

No one commented on what seem to me to be the essential (and interesting) aspects of this topic:

- How should an attempt at a scholarly treatment of rap lyrics deal with transcriptional uncertainties? Similar problems exist in editing texts from old manuscripts, which may contain unclear regions, scribal errors, mutiple copies with different material, and so on. There are several traditional solutions: which would be most appropriate here? Or is there a need (or an opportunity) for something new?

- How should we think about the meter of rap? In the particular case I discussed, an application of Temperley's theory of rock syncopation turns it into a rather traditional structure of rhymed couplets with 4+4 or 4+3 beats. Is this a good way to look at it, even though it ignores the patterns of performed beat alignments? What's the historical and stylistic distribution of this particular pattern? (My not-very-well-supported impression is that it was common 30 years ago, around the time of Superrappin', but was largely replaced later by other forms.

So I've put the original post and its comments (well, those I didn't delete earlier) here, deleted (most of) the repetitive bickering, retitled this one, and opened the floor to further discussion. Comments that contain no contribution beyond something like "I think line three started with 'you say'" or "I did/didn't hear 'fifty'" will be deleted — if you want to have a spirited debate about the proper textual transcription of these particular six lines (among the many thousands of lines in the anthology), feel free to set it up on your own blog, and I'll link to it here for those who want to participate.

Amy Stoller said,

December 4, 2010 @ 8:02 pm

The "fifty" is definitely there.

Really good transcription is an art as much as a science, but there is no excuse for not factoring prosody in when transcribing lyrics.

One pet peeve of mine is transcribing (or even just writing) numbers as numerals instead of spelling them out, if the work in question is intended to be sung or said aloud, rather than merely read to oneself. How, pray tell, is one meant to pronounce 101, absent more information?

I'm also puzzled by an anthology for which the editors don't bother to get the authorized version of the lyrics from those who crafted them in the first place.

Chris said,

December 4, 2010 @ 8:13 pm

I'm also unable to hear any "fifty" (or any other vocal) between the "heaven" and "seven".

[(myl) OK, enough with the "fifty". Either you're not listening carefully to the critical stretch, or I'm imagining things. But we know that the lyrics in music like this are hard to transcribe, so let's accept that this is an uncertain case, and move on.]

Peter said,

December 4, 2010 @ 8:41 pm

Listening carefully, with headphones, including to a slowed-down version, I can make myself hear a fifty it I try to, but it comes across more plausibly to me as a sharp intake of breath, with a click of some sort (which I’d place as a percussion instrument of some kind) about halfway through — so the click becomes the t, while the sibilance of the breath on either side becomes the f’s. I don’t claim 57-ers are imagining it entirely, but it’s not that us 7-ers aren’t listening carefully: as you say, it’s one of those spots where transcription is genuinely difficult.

Are there not accepted ways (looking at the spectrograms, or something) to investigate questions like this less subjectively? One could imagine contexts (transcription of evidence in court, for example) where this sort of thing could become very important! And it would certainly nice to have an option somewhere between “I hear this”/“I hear that”/“I hear this, with knobs on!” and just giving up on it as ineffable.

[(myl) Even relatively clear recordings, without background music and so on, are full of cases where different people hear different things — depending on material, transcription practices, training, time spent in transcription, etc., we can expect maybe 3-5% of the words to differ between two independent transcriptions. (If the transcribers are journalists, we can expect 40-60% of the words to differ ;-)) Recordings of poorer quality may have much higher inter-transcriber disagreement rates, and often pose issues that are eternally unresolved, like Neil Armstrong's "One small step for ((a)) man" (see here and here, etc.) — but even a better recording might leave similar issues in controversy.

I think that commenters in this case are focusing on the wrong thing. There are some transcriptions in The Rap Anthology that are clearly, intersubjectively, flat wrong. These should have been fixed. There are others that are uncertain. These should either have been checked with the authors, or indicated as uncertain with the conventional transcription signal of (( … )), or footnoted, or all of the above. We can all hope that future editions will do better.

Meanwhile, I at least also hope that future editions will consider the problem of meter. If nothing else, a careful attempt to transcribe the meter-to-text alignment will fix the obvious transcriptional mistakes. But more important, it makes no sense to try to document rap as poetry without trying to understand its meter.]

J. Goard said,

December 4, 2010 @ 9:08 pm

Wow, a truly flagship LL post disguised as another mondegreen list!

Here in Korea, where everybody sings in noraebang 'singing-rooms', I've become intimately familiar with rap mondegreens. May have picked up a few of them myself :-(, but at least I know that Eminem said

and these times are so hard

and it's getting even harder

trying to feed and water my seed

plus teeter-totter

caught up between being a father and a primadonna

rather than the incongruously self-deprecating

plus see dishonor

What's interesting is that whoever provided the noraebang lyrics got many difficult sections right, but garbled some fairly easy ones.

Brian said,

December 4, 2010 @ 9:23 pm

Wow. I've listened to the thing a dozen times now, and it boggles my mind that anyone can hear a "fifty-". I do hear the intake of breath, but I can't make myself hear it as a two syllables. It goes by so fast that there's barely enough room for an inhale. Were it not for the other posters who claimed to hear it clearly, I would have thought it was an elaborate joke.

[(myl) Did you listen to the whole thing, or to the crucial passage here (which I transcribe as "…sound like heaven / fifty seven sixty five …)? As for length, the period of time between the end of "heaven" and the start of "seven" is about 270 msec. long, which is just about exactly the same as the duration of "heaven" and the duration of "fifty", and just a bit more than we expect for two minimal time-units in this section of the rap, where I count 28 minimal time-units in 3.644 seconds between the start of "one" and the start of "heaven", for an average of 130 milliseconds. But anyhow, as too often happens, commenters have zeroed in with laser-like intensity on a footnote to a footnote. Let's drop the whole "fifty-or-not" business, OK?]

Mfahie said,

December 5, 2010 @ 12:06 am

I wonder if it didn't occur to you that music notation would be the best tool, or if you discarded it as your notation for some reason. I could re-notate this tomorrow using standard music notation if you're interested, although I'm not 100% sure that I could post it.

[(myl) You could represent each line as four bars of 4/4 time, but I don't think it would add anything. On the contrary, it would obscure the relationship to the meter of traditional English accentual-syllabic verse, and it would be harder to grasp for people who haven't learned to read musical notation. It would be easy enough to do from a technical point of view, using LilyPond or Finale or whatever, and the result could straightforwardly be posted as an image. But as I said, I think that in this case it would be a step backwards.

For more complex meters, such as those discussed here, here, and here, the use of traditional musical notation can actually be a hindrance to understanding even for those who can read music well.]

matt said,

December 5, 2010 @ 12:09 am

Maybe I missed it in one of the comments, but did anyone else notice that the book transcribes the second sequence of numbers not as 7-6-5-4-3-2-1 but as the even more wrong 7-6-4-5-3-2-1?

[(myl) Good point. This reinforces Devlin's claim that the textual scholarship in TRA is (at least sometimes) remarkably slipshod. It's not clear to me whether the whole book is like this, or these are scattered lapses. (Update — or maybe it just underlines the problem of variant versions….]

Ran Ari-Gur said,

December 5, 2010 @ 10:20 am

@matt: In the sidebar to the second Slate article, you'll find that the editors state, "To the casual eye it looks like we inadvertently transposed '4' and '5' here. But on the original Enjoy recording of 'Superrappin′′ from which we drew our transcription, Melle Mel does indeed reverse the numbers."

[(myl) Another good point, which reinforces the relationship to traditional textual scholarship and the problem of dealing with variant versions.]

mfahie said,

December 5, 2010 @ 12:07 pm

OK. I figured there was some reason. I personally tried really hard to read & recite from your X-o diagram, and wasn't quite correct, whereas I would have read the music easily, but I understand your system's first goal is not to have the reader be able to easily reproduce the notated rhythm, but to be able to analyze it with respect to other poetry. I see how music notation would further obscure such a relationship.

Another related rhythmic point I'm interested in is the shift from "simple" rhythms in early rap, ie. the type of rhythms that could be easily notated in 4/4 time, to the much more sophisticated rhythmic delivery that characterizes more contemporary rap. And how to notate that!

[(myl) An excellent question, to which I don't have a satisfactory answer.]

Craig Russell said,

December 5, 2010 @ 12:12 pm

For what it's worth, I think the fourth line in the passage in question is pretty clearly:

"rappin' like hell and think it sounds like heaven."

I study ancient Greek oral poetry (specifically the Iliad and Odyssey) and I think an issue that has been raised for Homer is actually pretty relevant here as well: for a poetic form that is primarily oral, and is recreated time and again in performance, can there be a single authoritative version of the text?

People have argued that the Iliad and Odyssey existed either exclusively or primarily as oral performances for centuries, and that they were performed by bards who had the ability to rapidly and extemporaneously create lines of dactylic hexameter using a complex system of formulas. Because texts of the poems did not come into existence until the poems had existed for many centuries, and because performers of the poems would likely produce different versions of "the same" line or passage in different performances, is it even possible to say that there is one authoritative version of a line that should be printed in a modern edition of the text?

I should note that the view exactly as I've just expressed it is not held by every Homeric scholar (far from it!), and that the situation is not exactly analogous to modern rap, because we have audio recordings of the songs in question — if we're willing to agree that "the lyrics to the song Superrappin'" means the same thing as "the words sung in the recording of Superrappin' that was released in 1979". But as this post and the comments following it have shown, different people can listen to the same recording and hear very different things.

Some have suggested turning to the songs' creators and asking for written copies of the lyrics. But is it necessarily the case that even the original author's copy of the lyrics would give a definitive answer to what the lines recited in the recording are? It seems to me unlikely that rappers in the studio are reading carefully from a written version; the process of recording take after take after take will inevitably involve improvisation and variation, whether intentional or unintentional (random example off the top of my head: I've heard that John Lennon annoyed the other Beatles during the recording session for "Baby You're A Rich Man" by repeatedly singing the lyric "baby you're a rich man too" as "baby you're a rich fag Jew").

Anyway, my point is that turning to Melle Mel's original written copy of the lyrics for this song (if it still exists, and if it ever existed) would not necessarily resolve the question. If we asked Melle Mel to write out what he considers the correct lyrics to the song from memory, there would likely be variation from the recorded version. If we asked him to transcribe what he said by listening to the recording, he would just be another listener offering his opinion about what the recording says; perhaps an extremely reliable one, but it is unlikely that he has a perfect memory of what he meant to say in one take of a recording 31 years ago.

But to return to my original point: it is not a simple thing to say that there is such a thing as the definitive lyrics of a song. In modern rap music, what we call "a song" is a complex negotiation between an original act of creation, one or many studio recordings and releases, and an ongoing set of performances. Singers continuously reperform their songs, and — particularly in the genre of rap where there is a whole subgenre called "freestyle" involving simultaneous composition and performance — each performance will be a little different from the last. It is not necessarily valid to say that you can publish a written version and call it "the lyrics" to a song.

[(myl) Excellent points. Something else that's relevant to the particular lines under discussion is the wider background of "counting" lines, both before and after this performance, such as these from J-Kwon's Tipsy (as transcribed online — I haven't checked a recording):

1, here comes the 2 to the 3 to the 4,

everybody drunk out on the dance floor, […]

here comes the 3 to the 2 to the 1,

homeboy trippin' he don't know I got a gun, […]

2, here comes the 3 to the 4 to the 5,

now i'm lookin at shorty right in the eyes, […]

here comes the 4 to the 3 to the 2,

she started feelin on my johnson right out the blue, […]

3, here comes the 4 to the 5 to the 6,

i could spend ? i aint gotta say i'm rich, […]

here comes the 5 to the 4 to the 3,

hands in the air if you cats drunk as me,

In other words, there's not just variation by the same performer, but also trading back and forth of shared fragments and line-types. This is better documented for some kinds of oral traditions than for Homer, obviously, since in Homer's case we don't have a sample of the work "he" represented.]

Adrian Bailey said,

December 5, 2010 @ 3:44 pm

For some songs there are six versions: (1) what the singer intended to sing, (2) what s/he actually sang, (3) what was published officially, (4) what was published inoffically, (5) what people think s/he sang, and (6) what s/he wishes s/he'd sung. Should a book of lyrics contain (1), (2) or (3)? or all three?

I mention version (6) because if you go back to an artist in an attempt to clarify the lyrics, you may not get an honest answer.

Pflaumbaum said,

December 5, 2010 @ 4:28 pm

@ Craig – I think it's pretty clear that at least large parts of the Iliad and Odyssey had become 'fossilised', because of things like hiatus between vowels retained where there would once have been a ϝ. You'd expect those verses to be prime candidates for recasting to avoid the hiatus, if there were no 'authorised version'.

Which isn't to say that they didn't originate from a long period of creative composition and re-editing, surely they did.

By the way, is there much good work on metre in hip-hop? Can anyone recommend anything?

[(myl) I'd be interested to learn about such work as well. I've searched without finding much of anything. As I suggested in the body of the post, I think it's a subject that would repay study.]

PSE said,

December 5, 2010 @ 5:47 pm

@Plaumbaum, myl

There's an interesting discussion of rap's meter and scansion in Book of Rhymes .

While I don't know any generative linguistics papers that look at hip hop meter per se, MIT's Jonah Katz has discussed it to some extent. Sources therein would also be, less directly, relevant.

Craig Russell said,

December 5, 2010 @ 5:48 pm

@Pflaumbaum (at the risk of incurring the μῆνιν Λιβερμάνοιο by going too far off topic)

As I said, this is not something that everyone agrees on. I outlined the version of Homeric transmission I presented (introduced by "people have argued", e.g. these people: http://www.homermultitext.org/) because I thought it was a good analogy for rap, not because it's necessarily the necessarily the version I think is correct in the particular case of the Iliad and Odyssey — as a matter of fact, I do tend to agree that they were probably fixed in writing very early, for a variety of reasons.

But to your specific point about fossilization, I think the digamma argument demonstrates fossilization more on the small level of short formulas (for heroes names with epithets etc) than on the large level of long passages of text, as was demonstrated by Milman Parry. Random example that happens to be in front of me: Odyssey 13.8 ends in the formula αἴθοπα οἶνον (aithopa oinon: sparkling wine), where the fact that the final alpha of the first word doesn't elide points to the former existence of a digamma at the beginning of οἶνον. But I think the reason for this is not because the text of book 13 of the Odyssey was fixed early, but because as part of the oral poetic tradition Homer inherited the fixed formula αἴθοπα οἶνον to use in the final two feet of a line.

Again, sorry for straying so far from the topic!

Pflaumbaum said,

December 5, 2010 @ 6:13 pm

@ Craig – thanks, you know a lot more about this than I do and my Homeric Greek is rusty. I shall have a look at the link and meanwhile I'mma shut the f*ck up yo.

Except to ask: do you know whether it's a similar case – formulaic phrases – with words like νέφος that are thought to make position because of an original laryngeal?

andrew said,

December 5, 2010 @ 7:31 pm

Pflaumbaum: νέφος and other words that begin with nasals may make position on the analogy of formulae involving words beginning with nasals that make position because they once started with *sn- or *sm- (e.g., νυός for *snusós).

Aaron Binns said,

December 6, 2010 @ 11:59 am

I wonder if they even consulted the keepers of http://www.ohhla.com. I also remember huge flame wars on the hip-hop and rap-related alt and rec newsgroups back in the mid-1990s. The heated and ongoing debate over the chorus to A Tribe Called Quest's "Electric Relaxation" would make for an interesting study in itself.

Paul Devlin said,

December 6, 2010 @ 12:59 pm

Dear Mr. Liberman,

Thanks for your kind words. I'd just like to point out that there are two different versions of "Superrapin'," as Adam Bradley notes in his comment to my first article on Slate. (His comment is one of the earliest comments on my first article, on November 4.)

I was listening to one version, while the editors included a different one in the book. As they say in their replies to my questions in article #2 ("It was Written"), they were transcribing the Enjoy Records version. (Many rap songs have several variants [clean versions, explicit versions, remixes, and so on] and the Anthology doesn't note which version is being included and why.) I give some examples of this (and ask why) in my reply to Bradley's comment on November 4.

Kaviani said,

December 6, 2010 @ 4:30 pm

"How should an attempt at a scholarly treatment of rap lyrics deal with transcriptional uncertainties?"

With minimal ado. The "flow" of hiphop cannot be bothered with strict parameters and universal codification. I know this flies in the face of scholarly treatment, but the average lyricist will probably have the same attitude.

"In the particular case I discussed, an application of Temperley's theory of rock syncopation turns it into a rather traditional structure of rhymed couplets with 4+4 or 4+3 beats. Is this a good way to look at it, even though it ignores the patterns of performed beat alignments?"

Good enough, but I would consider it a fundamental that's still common for studio styles including stupid offshoots like nerdcore (mostly). Freestyle remains the "real" hiphop and offers plenty of exceptions. Also, the study should be expanded beyond the US and English itself. Genod Droog and Y Diwygiad, for example, rap in Welsh and that's a very confounding and interesting mashup. Spanish has other merits and challenges; etc.

hip hop lyrics said,

December 8, 2010 @ 3:25 pm

3 years ago I plugged 10,000 hip hop lyrics files into AntConc. Was trying to make an 'OED' of hip-hop, you know, something descriptive. I come from a classics background and was lookin' at it also as a transcription challenge…

It was fun and a total mess.

In addition to the great points by @Craig Russell above, there are further problems with accurate transcription:

– Vocal samples and background singing interspersed among the main vocal line. Especially when the samples are chopped up words or phrases not even necessarily delivered by the artist but a fundamental part of the track nonetheless.

– Group tracks or guest artists or collaborators rapping in the background, often at the same time as the main vocal track. Untangling Wu-tan? Ugh!

– Mixtapes vs. official releases vs. leaked releases vs. live performance etc. etc. (already mentioned)

– Puns and wordplay, sometimes involving place and people names that are unlikely to be familiar to the listener. Sometimes involving intentional mis-pronunciation. Some Jay-Z songs are nonstop double meanings and puns. When you transcribe, which way to spell it?

– The meaning embedded in tonality and pronunciation. Ludacris is a great example of this. The way he draws out certain words.

– Orthography in general, but especially with song titles and albums. If the name of the album or track includes a noun that is pluralized with 'z' instead of 's', but otherwise no lyrics are published in the liner notes, is that to mean that the artist meant for any instance of such a word in the song to be transcribed the same way? Not to get too vulgar, but how to spell bee-yotch? It's a different word(s) than 'bitch' and artist to artist may have different meanings or appropriate spellings.

– Regional stuff. Southern rap vs. west coast etc etc

– What about midstream totally different language stuff, like Snoop's 'izzle' this and that?

More rap talk like this on language log please. Shit is thorny.

Palindromes and Other Word Play | Wordnik ~ all the words said,

November 11, 2011 @ 10:04 am

[…] lists several mondegreens in the form of misheard lyrics, while Mark Liberman at Language Log takes a look at the Anthology of Rap, which may be better named the Anthology of […]

Chirayu said,

August 4, 2012 @ 11:09 am

Doesn't help that unlike most other releases, hip hop albums don't contain lyrics inside the album sleeve. Personally, as someone who is by no means a linguist, and rather, is just a man who's been enjoying hip hop for close to two decades now, I see no problem. With that said though, I've witnessed the growth in rap, and one thing that's definitely improved is recording equipment. With that, it's become easier and clearer to hear what the artist is saying. Nowadays, too, it seems like less and less rappers are staying in tune with the hip hop culture, so we're hearing less vernacular than to what was being heard in the late 80s and early 90s.