Your brain on ___?

« previous post | next post »

A couple of days ago, the New York Times published another in its Your Brain on Computers series, which "examine(s) how a deluge of data can affect the way people think and behave". The latest installment is Matt Richtel's "Growing Up Digital, Wired for Distraction", 11/21/2010:

Students have always faced distractions and time-wasters. But computers and cellphones, and the constant stream of stimuli they offer, pose a profound new challenge to focusing and learning.

Researchers say the lure of these technologies, while it affects adults too, is particularly powerful for young people. The risk, they say, is that developing brains can become more easily habituated than adult brains to constantly switching tasks — and less able to sustain attention.

A couple of months ago, I found reasons to be skeptical about some aspects of Mr. Richtel's earlier contributions to this topic ("Tracking a factoid to its lair", 8/31/2010; "More factoid tracking", 9/1/2010; ; "Are 'heavy media multitaskers' really heavy media multitaskers?", 9/4/2010). His latest installment — a hefty one, at 4200 words — is a similar combination of scary anecdotes and scarier science. I'm not going to spend much time on the anecdotes, except to point out the connection to other stories that people have told over the years about the ways that teenagers find to avoid doing their homework. But the science deserves a closer look.

In particular, Richtel cites a study suggesting that video games disrupt brain-wave patterns in sleep and cause subjects to forget vocabulary words:

In an experiment at the German Sport University in Cologne in 2007, boys from 12 to 14 spent an hour each night playing video games after they finished homework.

On alternate nights, the boys spent an hour watching an exciting movie, like “Harry Potter” or “Star Trek,” rather than playing video games. That allowed the researchers to compare the effect of video games and TV.

The researchers looked at how the use of these media affected the boys’ brainwave patterns while sleeping and their ability to remember their homework in the subsequent days. They found that playing video games led to markedly lower sleep quality than watching TV, and also led to a “significant decline” in the boys’ ability to remember vocabulary words. The findings were published in the journal Pediatrics.

Markus Dworak, a researcher who led the study and is now a neuroscientist at Harvard, said it was not clear whether the boys’ learning suffered because sleep was disrupted or, as he speculates, also because the intensity of the game experience overrode the brain’s recording of the vocabulary.

“When you look at vocabulary and look at huge stimulus after that, your brain has to decide which information to store,” he said. “Your brain might favor the emotionally stimulating information over the vocabulary.”

The research in question was reported in Markus Dworak et al., "Impact of Singular Excessive Computer Game and Television Exposure on Sleep Patterns and Memory Performance of School-aged Children", Pediatrics 120(5): 978-985. Here's their summary:

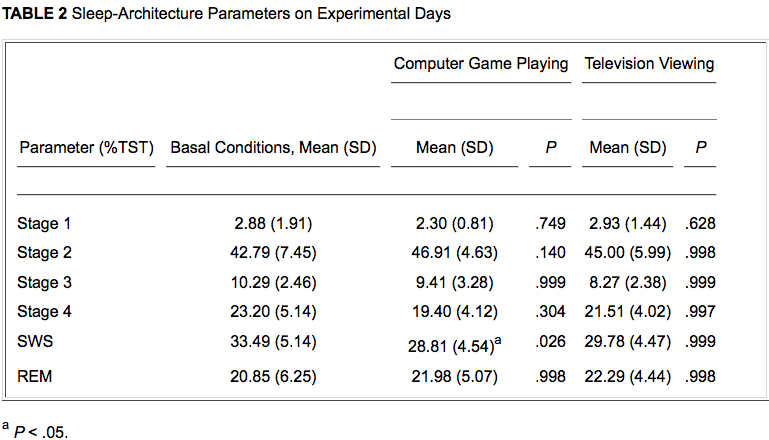

METHODS. Eleven school-aged children were recruited for this polysomnographic study. Children were exposed to voluntary excessive television and computer game consumption. In the subsequent night, polysomnographic measurements were conducted to measure sleep-architecture and sleep-continuity parameters. In addition, a visual and verbal memory test was conducted before media stimulation and after the subsequent sleeping period to determine visuospatial and verbal memory performance.

RESULTS. Only computer game playing resulted in significant reduced amounts of slow-wave sleep as well as significant declines in verbal memory performance. Prolonged sleep-onset latency and more stage 2 sleep were also detected after previous computer game consumption. No effects on rapid eye movement sleep were observed. Television viewing reduced sleep efficiency significantly but did not affect sleep patterns.

CONCLUSIONS. The results suggest that television and computer game exposure affect children's sleep and deteriorate verbal cognitive performance, which supports the hypothesis of the negative influence of media consumption on children's sleep, learning, and memory.

The computer game was Need for Speed—Most Wanted. The boys (all 11 subjects were male) could choose among the movies Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Star Trek: Nemesis, and Mary Higgins Clark's Loves Music, Loves to Dance. (Since all of these are longer than the 60 minutes alloted to the experimental exposure, it's not clear whether the kids were just cut off arbitrarily an hour into the film, or what.)

The effects on "Sleep architecture", though statistically significant, were somewhat underwhelming, and apparently inconsistent with some previous studies:

To our knowledge, only 1 study previously examined the effects of media consumption (computer game playing) on sleep patterns in children. In accordance with Higuchi et al, we used polysomnographic measurements to define sleep stages and sleep latencies. In both studies, a significant increased SOL after singular excessive computer game playing was observed compared with control conditions. Contrary results were detected in sleep stages. Whereas Higuchi et al noticed less REM sleep and no changes in SWS after computer games, we detected more sleep in stage 2 and reduced amounts of SWS but no effects on REM sleep. The decrease in SWS after computer game playing in this study may reflect children's high arousal state. Differences in the age of the participants, type of computer game, place and type of polysomnographic measurements, and sleep time may be reasons for the different observation.

In other words, apparently, it all depends. And what about the effects on "sleep architecture" of playing monopoly or ping-pong? Or having an argument with your parents about playing computer games? Presumably that all depends, too.

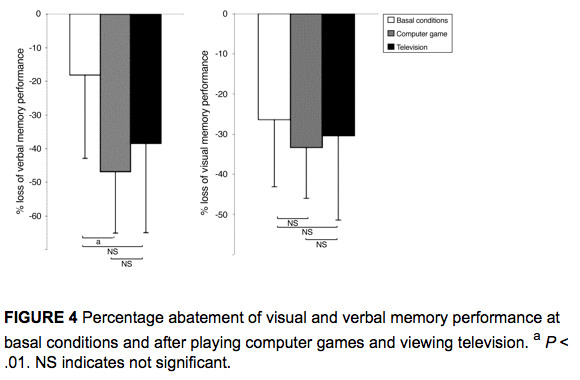

Another interesting finding was a significant decline of verbal memory performance after computer game playing compared with basal conditions. Modern neuroscientific theories support the notion that strong emotional experiences, such as computer games and thrilling films, could decisively influence learning processes. Because recently acquired knowledge is very sensitive in the subsequent consolidation period, emotional experiences within the hours after learning could influence memory consolidation considerably. Interactive video games are challenging, sometimes frustrating, exciting, and often surprising, and during playing, individuals may experience a range of emotions accompanied by physiologic changes. In addition, studies with positron emission tomography scans showed a significant release of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain during video game playing. Dopamine as well as norepinephrine are thought to be involved in learning, reinforcement of behavior, emotion, and sensorimotor coordination and thus able to influence memory processing decisively.

Indeed, playing Need for Speed did decrease these 11 boys' average retention of vocabulary learned shortly before playing:

The effect size was not enormous — and the difference between an hour of Need for Speed and an hour of television was small. I wonder, again, what the effect of other ways of spending time might have been. If a study were to show that doing crossword puzzles and playing scrabble also affects sleep cycles and interferes with the consolidation of verbal memory, would the New York Times cite it in an on-going series ("Your Brain on Word Games") about aging boomers' retreat into a fog of affectless verbiage and decontextualized competition?

The idea that new technology causes mental, moral, and social decay is an old one. Passing over in silence those who warned our ancestors about the disastrous effects of writing and printing, let's pause briefly to note the role that the Times assigned in 1924 to the telephone, that "most persistent and the most penetrating" aspect of "the jagged city and its machines", which "go by fits, forever speeding and slackening and speeding again, so that there is no certainty" ("And the town takes to dreaming", 9/1/2010).

More than six years ago, I took a look at Camille Paglia's contribution to the modern genre of Viewing Technology with Alarm ("Balm in Gilead", 4/16/2004). And then there was the Great "Email Lowers IQ More than Pot" episode of 2005 ("Quit email, get smarter", 4/23/2005; ;"Never mind", 5/3/2005; "News Flash: The Effect of Politics, Athletics and Sex on IQ", 5/3/2005; "An apology", 9/25/2005).

What all these have in common is a high ratio of stereotype and anecdote to fact. And the Dworak et al. study strikes me as so small and so under-controlled that its inclusion in Richtel's article doesn't really change that ratio very much.

I'm open to the hypothesis that cell phones, video games, and laptops are destroying the brains of our youth. But surely this idea is important enough to deserve more serious investigation than anyone seems to have given it so far. The constant ostinato of Viewing With Alarm somehow never translates into serious large-scale studies of causes and effects — which leads me to conclude that the whole thing is just ritual inter-generational hand-wringing.

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Your brain on ___? [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

November 23, 2010 @ 7:56 pm

[…] Language Log » Your brain on ___? languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2799 – view page – cached November 23, 2010 @ 6:16 pm · Filed by Mark Liberman under Psychology of language, The language of science Tweets about this link […]

maidhc said,

November 23, 2010 @ 9:30 pm

"The risk, they say, is that developing brains can become more easily habituated than adult brains to constantly switching tasks — and less able to sustain attention."

Surely playing a video game for hours straight is sticking with the same task. As contrasted with, say, reading a newspaper, where one hops from article to article on different subjects. Or watching a film with constantly changing scenes (unless it is an Andy Warhol film).

The research results seem to show, if anything, that doing the same thing over and over repetitively disrupts your sleep pattern.

If you observe kids learning skateboard tricks, you will see that kids have no trouble at all sustaining attention on a single task if it is something that interests them. Similarly with mastering a video game.

Chris said,

November 23, 2010 @ 10:15 pm

What!? Camille Paglia has contributed to cultural alarm!? I'm shocked! Shocked!

Keith said,

November 23, 2010 @ 10:26 pm

The key point in Fig. 4 left, on verbal memory performance, is that BOTH TV and computer games had a loss, compared to 'basal conditions' but the difference between TV and games was trivial. There is no justification, in those data, for singling out computer games; except, of course, cultural prejudice.

[(myl) Well, there's one of those little paradoxes of statistical "significance": the difference between basal and video-game conditions is "significant", but the difference between basal and TV conditions is not, even though the difference between video-game and TV conditions is also not significant. In the curious land of (some) psychological discourse, this means that "Only computer game playing resulted in […] significant declines in verbal memory performance".

I've often noted with admiration R,A, Fisher's appropriation of the term "(statistically) significant" to mean "a deviation whose probability of being due to sampling error is less than 5 percent". Surely this is one of the greatest public-relations master-strokes in the history of science.]

Garrett Wollman said,

November 23, 2010 @ 11:38 pm

So why isn't NIH or the Department of Education funding the sort of large-scale studies required to validate these sorts of results? Surely a few million dollars would allow a large and diverse enough sample size to at least say with more certainty whether a "video game effect" exists at all.

Sarah C. said,

November 24, 2010 @ 2:44 am

Two comments.

First, Daphne Bavelier and colleagues have been showing for several years now that there are some positive effects of playing video games (just Google-Scholar Green and Bavelier). This includes some training studies in which non-video-game-players were assigned to a first-person-shooter game or a "control" game, and only the f-p-s-trained people improved on visual attention measures.

Second, that article strikes me as a fishing expedition. I'm going to wager a guess that in the data analyses in Table 2, they didn't control for familywise alpha. Getting ONE significant test out of six is really not surprising (about a 1 in 4 chance with an alpha level of .05). That's not even counting the further analyses they conducted.

kenny said,

November 24, 2010 @ 10:07 am

I have a few things to say. Firstly, I consider myself a scientist and I know that anecdotal evidence doesn't mean squat in science. But there comes a time when a phenomenon is prevalent that you don't need science to tell you of its existence, instead perhaps only of its severity, and even then, sometimes it takes a while for scientists to come up with a good way to empirically quantify these things.

I'm young, and I have experienced for myself how constant exposure to the internet and games have severely harmed my own ability to concentrate and focus on tasks for long periods at a time (meaning, any longer than half an hour). But moreover, all my friends are having the same problem. Now, whether this is a transient problem that would go away if we stopped using the internet so much (as opposed to a more inherent problem of altered wiring, developmentally speaking) is an important and interesting question, but it seems in a way immaterial, since our world is only becoming more technologically integrated, and the problem is only going to get worse. This is one of the main things I worry about, for myself, for my students, for my own future children, and for our society at large.

Carol Saller said,

November 24, 2010 @ 10:40 am

Please keep poking sticks at studies! The older I get, the more "inter-generational hand-wringers" I know. I'm collecting your columns for ammunition.

Spell Me Jeff said,

November 24, 2010 @ 11:06 am

Part of the trick here is actually specifying what the problem is. If we casually lump games and the Internet under the same umbrella, we are already headed down the wrong path.

Anecdotal evidence: I am on the Internet nearly every day of my life, often for several hours. I spend a lot of that time reading news feeds at Yahoo or the Chronicle or even LL. I do not game, I do not Facebook. In short, my engagement with the Internet is generally pretty calm, not characterized by huge jolts of adrenaline or other hormones.

Given that, I would hypothesize that any after-Internet effects will differ from those of someone who had been gaming online, viewing online porn, or tweating her 50 BFFs. But also that those effects would differ, as Mark suggests, from those of someone who has been playing in-the-flesh poker, washing dishes, or talking on the phone with Jed and all his kin.

So what exactly is this phenomenon that has our britches in a knit? Seems to me, considered from a psychological perspective, the Internet (not to mention other digital technology) is most likely a collection of phenomena, and that the most reasonable hypotheses to be tested will break these phenomena down as discretely as possible.

At least the study in question did limit itself to gaming behavior, as Dworak's title makes clear. But I hardly think that calls for Richtel's more general claim about "growing up digital."

OTOH, Dworak is clearly prepping Richtel and others with statements like this:

Why bring "thrilling films" into the picture? Why not barroom brawling or even driving to Wal-Mart for ice cream? Has anyone tested the effects of playing Monopoly after homework? Is such a test even in the works? It's not as if the potential for such a test hasn't been available for, what, 80 years?

Further, given the nature of the experiment, aligning games with "thrilling films" seems absurd on its face. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban and Star Trek: Nemesis gereally ARE considered thrilling films. Wasn't the method of this experiment designed to show whether the after-effects of these two phenomena would be different? Why then yoke them together?

Terry Collmann said,

November 24, 2010 @ 12:51 pm

Kenny – really, mate. I'm 58, I'm quite capable of playing a computer game for 14 straight hours, and also listening to Beethoven's 9th for 80+ minutes, or reading a novel for 14 straight hours. Your anecdotal narrative is no more proof of anything than mine.

Stephen Nicholson said,

November 24, 2010 @ 2:00 pm

I want to see a study that compares kids playing video games to racing hot rods like in Grease.

"In this study we compare the effects of racing hot rods to playing video games. We conclude that playing video games is more likely to cause the participants to brake into song because of Rock Band."

Peter said,

November 24, 2010 @ 3:07 pm

@kenny: I’m moderately young, -ish maybe (well, mid 20’s), and use the internet many hours most days, and have serious trouble with concentration, procrastination, discipline at work, and so on, and yes, many of my friends have similar problems.

But without a control group of friends who don’t use the internet so much, I don’t see how we can fairly put the blame on it! Read old novels, watch old films: in previous generations too, teenagers and twenty-somethings were shown as feckless, lazy, slow to adapt to the responsibilities of work and a career.

So I’m not sure there’s necessarily anything new going on. The internet may be the main outlet for our generation’s procrastination and distractibility, but that doesn’t mean it’s the cause.

Brett said,

November 24, 2010 @ 3:22 pm

@myl- In these cases, "statistically significant" isn't even being used to mean "a deviation whose probability of being due to sampling error is less than 5 percent." Instead it's "a deviation that would only occur due to sampling error 5 percent of the time in the absence of any effect." It's the old confusion of a frequentist result for a Bayesian one. Many times, I've seen this misused to claim that a "statistically significant" but extremely outlandish results is 95% likely to indicate a new phenomenon in operation.

Clayton Burns said,

November 24, 2010 @ 4:10 pm

Well done, Mark. Appended is info on the best article I have seen in The New York Times this year on IT in science, with brilliant animations. (So Sunday's NYT column on the need to turn off all the gadgets and concentrate on the texts was a silly one).

IT is just another method of presenting information. It is as if I track books ("The Emperor of All Maladies," the best I have seen in 2010), magazines (The New Yorker), and newspapers (The Sunday New York Times), in a deliberate effort to create information response plasticity. In this project, no one form of information is inherently evil.

What matters is what you do with the source. Facebook could be a turntable for the greatest science book (Bruce Alberts's "Molecular Biology of the Cell," which honors life sciences students could absorb in high school), and simulations such as those in Erik Olsen's article:

Where Cinema and Biology Meet

Robert A. Lue ANIMATION An image from the video “Powering the Cell: Mitochondria.”

By ERIK OLSEN NEW YORK TIMES Published: November 15, 2010

What never ceases to amaze is the lack of imagination of those who cannot understand that the way to "combat" IT is to turn it to better purposes.

D.O. said,

November 24, 2010 @ 5:16 pm

In this situation, it would be prudent to make a 3-way comparison (ANOVA). But I am too lazy to read the paper, never mind do the calculations…

John Ellis said,

November 24, 2010 @ 8:54 pm

There has been quite a lot of this crap in the UK too.

Earlier this year Vaugaun Bell of mindhacks.com gave a nice presentation to the House of Lords (!) you can find here http://mindhacks.com/2010/03/18/lords-ladies-and-video-games/

And here's Ben Goldacre dealing with the 'facebook gives you cancer' brigade http://www.badscience.net/2009/02/the-evidence-aric-sigman-ignored/

D said,

November 26, 2010 @ 7:58 am

On the other hand, I'm fairly sure that watching Star Trek: Nemesis made me a little dumber…

2010-11-26 Spike activity « Mind Hacks said,

November 26, 2010 @ 4:14 pm

[…] you LanguageLog for the keeping it real coverage of The New York Times' odd anecdote-led 'Your Brain on Computers' […]

Marcus said,

November 28, 2010 @ 10:40 am

Great work, Mark! Your point about the fact that they don't compare the video games to something like fighting with parents (or what about, say, kissing a girl for the first time? Or having a good ol' fashioned wrassling match?) I think says a lot about one of the basic problems with all the research and conclusions we see in this area — what is it exactly that these activities are supposed to be "worse" than? I'd like to think people aren't naive enough to just assume there was some kind of neutral, almost Edenic "before technology" state that everyone used to exist in, during which time learning was excellent and nobody ever got distracted so now any observed effect technology has on people is assumed to be bad, but it certainly does seem like that's one of the underlying assumptions.

Monday Morning Stepback: On Reviewing Conspiracies… | Read React Review: Rethinking romance and other fine fiction said,

November 29, 2010 @ 7:20 am

[…] one of a series of New York Times articles on the distractions of the digital age. Check out this terrific response from the Language Log. The intrepid folks there actually looked at the studies the Times cited, and found … a lot […]

Mike said,

December 2, 2010 @ 9:25 am

tl,dr

Aaron Davies said,

December 4, 2010 @ 11:43 am

@kenny: You're not a scientist and your observations are meaningless. Please come back when you learn something about how proof actually works.