Language has a way of turning pundits into fools

« previous post | next post »

Robert Fisk, the well-known linguistic paleoconservative, has been reduced to playing little games with his copy editors in order to create material for his columns ("Our language has a way of turning women into men", The Independent, 8/14/2010):

A week ago, in my front-page story on the Hiroshima commemoration, I planted a little trap for our sub-editors.

I referred to Vita Sackville-West as a "poetess". And sure enough, the sub (or "subess") changed it – as I knew he or she would – to "poet". Aha! Soon as I saw it, I knew I could write this week about the mysterious – not to say mystical – grammar of feminism and political correctness. At least, I guess feminism was the start of it all, for was it not in the Eighties and early Nineties that newspapers started turning feminine nouns into male nouns? This was the age, was it not, when an "actress" became an "actor", when a "priestess" became a "priest" – which does sound more sensible – and when a "conductress" became a "conductor". A policeman and policewoman have turned into "police officers" (even if they are constables).

Mr. Fisk suggests that we "take all this across the channel where – heaven preserve us – the difference between male and female is written into the very grammar of the French language", and claims that

… there's no hesitation in France in calling an actress une actrice (or une comedienne) or to call a woman pilot une aviatrice. In fact, if anything the French are increasing the verbal differentiation between men and women. Recently a female minister wanted to call herself la ministre (it didn't catch on) and at one point it was suggested that if Ségolène Royal became president, she would be Madame la présidente.

I'm not sure what point this cross-channel move is supposed to establish: that epicene occupational terms are against human nature? That the culturally-superior French would have allowed his use of poetess to stand? (Or perhaps, that Robert Fisk still has two thirds of a column to fill up?)

In fact, I'm not sure what direction French culture is taking on the specific issue of what to call female poets. Though poétesse is used, a quick web search also turns up plenty of examples where female writers of verse are called "poètes":

Elisabeth du Baret, poète pour petits et grands (link)

Katie Melua, poète jusqu'aux yeux (link)

Un Romand dévoile une Marilyn secrète et poète (link)

Devant la caméra, le chanteur Florent Vollant et Joséphine Bacon, poète innue et réalisatrice de documentaires, auront des rôles secondaires. (link)

In a 2007 discussion on the WordReference Forum, the question of what to call a female poet was answered by Alexa99 as

Un poète

Une poétesse. ( si vraiment c'est nécéssaire, car c'est horrible )

with Batuni chiming in that "Je suis d'accord avec Alexa99, les feminins en 'esse' sont souvent assez atroces : doctoresse, poétesse…. ogresse", and a moderator pointing to a couple of broader discussions here and here, which suggest that the overall situation with respect to gendered occupational terms in French is complicated, and may be moving in different directions in France and in Quebec. (FWIW, a couple of years ago, Heidi Harley reported some evidence that the whole French system of linguistic gender may be beginning to dissolve around the edges a bit: "You say feminine, I say masculine, let's call the whole thing off", 2/25/2008).

As for the general issue of gender in Romance-language occupational terms, a post earlier this year reported claims that Italy and Spain are moving in opposite directions ("Ludicrous, even derogatory?", 1/18/2010).

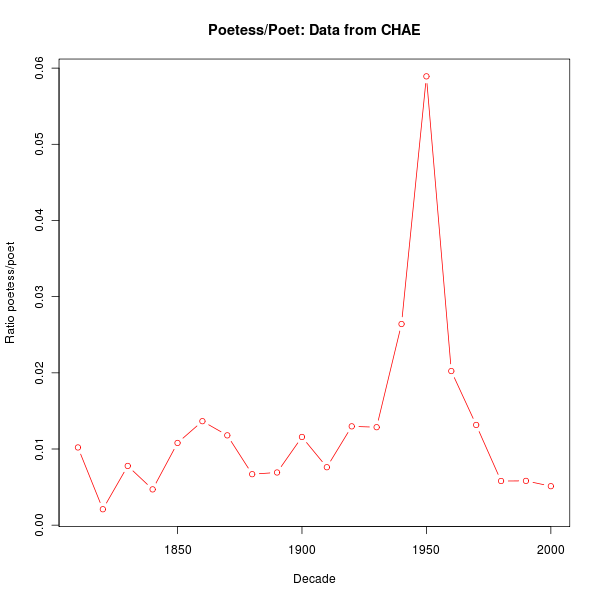

And it occurred to me to wonder what the historical pattern of poetess usage really is. So here's a graph of the ratio, decade by decade, of counts of poetess vs. poet in the Corpus of Historical American English:

Though this is from American rather than British English sources, it suggests that the Golden Age of Gender Clarity that Mr. Fisk is defending might actually have coincided rather closely with the first, formative decade of his own life.

The OED, in addition to offering a usage note about poetess ("The gender-neutral poet is now often preferred"), gives some evidence in its citations that some people have been uneasy about the word for more than two centuries:

1748 LADY LUXBOROUGH Let. 28 Apr. in Lett. to W. Shenstone (1775) 21, I am no Poetess; which reproachful name I would avoid, even if I were capable of acquiring it.

1903 Academy 17 Jan. 71/1 Jesse Berridge is a poet, not a poetess, to use a somewhat outmoded word.

Broadening the scope of discussion a bit, I can't resist linking to the most recent Subnormality, especially these panels:

[Hat tip to Stan Carey of Sentence First]

MattF said,

August 16, 2010 @ 10:20 am

Actually, I think 'ogresse' is fine.

Scott said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:22 am

Whenever I hear or see 'poetess' I want to shriek like a little boyess. Also, here in the most united Kingdom I occasionally hear "lady Doctor", most often said by an older citizen.

Nick Lamb said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:22 am

Maybe I missed an update, but isn't it possible that French linguistic gender was never any more solid and reliable than say, English pronunciation? Various LL comment threads suggest that lots of fluent English speakers are unaware of variants that would be considered ordinary by other speakers. They would confidently pick the "correct" pronunciation in a test, and never consider that all the other options presented may be right too.

Or do we have records that show ordinary French users from say the 1800s consistently used linguistic gender according to a single identifiable set of rules and so this is a recent phenomenon?

[(myl) This is a good point. The only evidence in Heidi's post is the difference between older and younger native speakers — which could be an apparent-time image of a historical change, or merely evidence for unexpected developmental delay in acquiring this aspect of language. (Or perhaps an uncontrolled difference in educational background?) There may very well be some more direct evidence out there, I don't know.]

Leonardo Herrera said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:30 am

In Spanish, it is perfectly good to say "poeta" and "poetisa", "actor" and "actriz". Down here in Chile our former president Michelle Bachelet was referred as "la presidenta Bachelet," as opposed to our current president which is usually referred as "el presidente Piñera."

Of course, sometimes the PC crowd gains enough traction and we get stupid things like "médico" instead of "médica", "ingeniero" instead of "ingeniera", "abogado" instead of "abogada" and so on. "Doctor" and "doctora" are still used, thankfully.

Robert Coren said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:44 am

Was it Audre Lourde who said "Being called a poetess brings out the terroristress in me"?

Lane Greene said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:47 am

He's also wrong on "madame la ministre" – for something that "didn't catch on", it's surprisingly common, appearing on almost 8 million French pages.

MikeM said,

August 16, 2010 @ 11:53 am

My wife the sociolinguist says that women are"marked," which I believe means that men are the norm and women are outside the norm — including adding the "wo" to "man" to show this outsidedness. "Policewoman" was used when they were outside the norm, but I hardly hear it any more, since the officer I see driving by is often female.

Jean-Sébastien Girard said,

August 16, 2010 @ 12:35 pm

There are differing opinions regarding whether "poète" is to be treated as epicene or not.

[(myl) Can you tell if there's any historical trend in one direction or the other?]

Funnily, the real problem style-wise in French is figuring ways to write gender neutral text without having to annoyingly duplicate every word that can take male or female endings.

Nathan said,

August 16, 2010 @ 12:53 pm

It makes little sense to draw on Romance languages to support the cause of English gendered nouns. English lost grammatical gender a long time ago, and we just have these few relict sex-marked nouns left. I don't have strong preferences on the word choices themselves, but the problem is the way people get all political about them. Most users of English are making mere choices of style, not trying to be oppressively patriarchal or revolutionarily feminist.

That said, poetess and most of those other terms sound somewhat old-fashioned nowadays. I predict actress will last the longest.

Shoe said,

August 16, 2010 @ 12:55 pm

Jean-Sébastien Girard: German has the same problem.

I always enjoyed listening to former Kanzler Schröder as he addressed delegates at the SPD conferences. Towards the end of his long speeches he starting losing the vigour or the will for the careful articulation of the oft repeated appellation Liebe Genossinen und Genossen (dear female comrades and male comrades) so that what emerged from his mouth was a slurry of esses and enns.

Karen said,

August 16, 2010 @ 1:24 pm

In studying Russian – a three-gendered language – I had an elderly professor (back in 1973) say, while explaining the concept of gender, that 'for instance, women are not poets but poetesses' (poehtessy) and there was something in his tone that said this was a value judgment, not just a linguistic one. So I asked "What about Akhmatova?"

And he said: "Ah! Akhmatova! Ona nastoyaschiy poeht!" (She's an authentic poet!)

So it's more than just grammatical gender…

J. W. Brewer said,

August 16, 2010 @ 1:29 pm

It's not clear to me that Vita S-W is better remembered for her poetry than for her novels (if one non-cynically assumes she is remembered at this late date for any of her actual writings rather than her various colorful personal entanglements). It's interesting to note that there's no English noun parallel for poetess for novel-writer (although I guess the phrase "lady novelist" is an imperfect parallel?). And the novel is the literary genre in English where it is easiest to find female writers inarguably considered in the first rank w/o the need for affirmative action, special pleading, or questioning of the criteria used for canonicity.

John said,

August 16, 2010 @ 1:50 pm

Modern Italian has the same issue. In this case it's been more or less resolved in favor of the masculine for titles. So a local mayor is "il sindaco" even though she's a woman. Some of this is due to words that had no working feminine form, due to women never occupying the roles (like the mayor), but this happens even when there's a perfectly good feminine in existence.

John Roth said,

August 16, 2010 @ 1:55 pm

J. W. Brewer said:

It's interesting to note that there's no English noun parallel for poetess for novel-writer (although I guess the phrase "lady novelist" is an imperfect parallel?).

Authoress. I've definitely seen it, but I'd hardly call it endangered. It's closer to dead and buried at the crossroads with a stake through its heart.

And to whoever said they expected actress to last the longest: I'll nominate waitress instead.

Christopher said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:14 pm

Oughtn't it to be "subbix"? Honestly, if one is going to be a peevish paleocon, one can use the proper feminine forms.

MJ said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:53 pm

@ Christopher–or "editrix," which is what I have on my license plate.

Jerry Friedman said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:53 pm

Cross-thread coincidence: the journalistic placement of this week in Fisk's "I could write this week about the mysterious – not to say mystical – grammar of feminism and political correctness."

@myl: On that graph, don't you have to control for how often female poets are talked about? Maybe a rise in the mention of them coincided with a decline in the use of poetess, giving that beautiful spike.

[(myl) That's exactly what I think probably happened: a major increase post-WWII in discussion of female poets, and a major decline post-1960 in use of "poetess" to describe a poet who happens to be female. I had a whole paragraph on this, with discussion of the hypothetical time functions of conditional probabilities involved — Pt("poetess" | FEMALE POET) etc. — but I deleted it on the grounds that it was too nerdy even for LL readers. Apparently I was wrong…]

No, I'm not planning to do the searching. Why do you ask?

Jo said,

August 16, 2010 @ 2:59 pm

John, I would disagree that anything has been resolved; this is quite a hot issue in modern Italian (judging by debates among Italian translators, anyway). Using terms like ministra, avvocata, revisora–or the feminine article with presidente, vigile, giudice, poeta, etc.–is a practice pooh-poohed by the anti-PC crowd, but I see it gradually catching on in the media, and in my humble, non-native opinion it serves a purpose: being able to refer to a female person with a feminine noun so as not to keep switching genders mid-discourse and generating confusion, while avoiding the strongly marked -essa.

Watching Battlestar Galactica dubbed into Italian, it was intriguing to note that Laura Roslin is always "la presidente". But whenever someone addresses a female superior, it's always "signore", never "signora". I suppose "sissignora" still doesn't sound military enough.

vanya said,

August 16, 2010 @ 3:03 pm

Waitress will last a long time, so will stewardess (Does anyone actually say "flight attendant" in daily speech?).

R. Ward said,

August 16, 2010 @ 3:15 pm

@Vanya

Actually, I don't know anybody who says "stewardess" in daily speech. It's almost always flight attendant, except for a few older people.

Boris said,

August 16, 2010 @ 3:18 pm

@Vanya, I never heard the word "stewardess" in daily speech in English from a native speaker. I've only ever heard "flight attendant".

Jonathan said,

August 16, 2010 @ 3:52 pm

"Poetisa" in Spanish is strongly marked as being old-fashioned and "cursi." It is still used, but I don't let my students use it.

dwmacg said,

August 16, 2010 @ 3:55 pm

It would be interesting to see the original headline in context–it's entirely possible that the three extra letters were cut to save space.

[(myl) It wasn't in a headline — the context as edited was "And we might do well to note how the poet and novelist Vita Sackville-West reacted to Hiroshima", towards the end of a 1500 word article.

(… as you could have found out for yourself by clicking on the link in the post…)]

Jean-Sébastien Girard said,

August 16, 2010 @ 4:15 pm

@myl I'm not sure what, if any trends can be described.

Grevisse & Goosse (Bon Usage, 14th ed., §487 R18) note: "Poétesse est péjoratif, comme avocate l'a été, pour ceux à qui déplaît la présence des femmes en dehors es sphères dans lesquelles une certaine tradition aurait voulu les enfermer" ["Poétesse and Avocate are pejorative as far as those who'd like for women to remain confined in traditional roles are concerned."]

"Poétesse" is old, and harkens right back to medieval Latin poetissa. There seems to be a feeling that the most well-known feminine, and all the newly coined ones (e.g. older négresse, gonzesse recent fliquesse, literary borgnesse, sauvagesse, diablesse, pauvresse…) are eminently pejorative, and wholly new coinages would be felt as at best ironic (e.g. clownesse). This probably goes to explain why "poétesse", where "poète" can act somewhat as an epicene (its ending is not obligatorily masculine or feminine, unlike many other words).

This problem does not seem to affect noble or religious titles (comtesse, abbesse, chanoinesse…). Nor does it affect "mairesse", at least in Quebec (despite a brief comment from Grev. & Goosse)

bfwebster said,

August 16, 2010 @ 4:35 pm

"actor vs. actress": The real question is, when will we stop having separate (Oscar, Emmy, Tony, etc.) award characters for male and female actors? ;-)

dwmacg said,

August 16, 2010 @ 4:36 pm

Thanks for the clarification, Mark. In my defense, I'm at work, links can be spotty here, the Independent site especially, and when I did look at his articles on the site I was looking for something referencing a poetess. Also, I became even more of an old doddering fool today.

Theophylact said,

August 16, 2010 @ 4:51 pm

Not until the Bechdel Test is no longer relevant.

J. W. Brewer said,

August 16, 2010 @ 5:15 pm

But if the edited text was "the poet and novelist Vita Sackville-West," what was Fisk's unedited draft: "poetess and novelist," with the obvious lack of parallelism, or perhaps "poetess and lady novelist," which would maybe be laying the gender-specific thing on a bit too thick? If he were going to avoid limiting her to just one genre, he perhaps ought to have just stuck to "authoress" or "lady writer." (To my ear, "lady writer" was not all that reactionary or archaic-sounding as of 1979 when the Dire Straits song of that title was much on the radio — I see that wikipedia hypothesizes that the writer in question was Marina Warner.)

Adrian Bailey said,

August 16, 2010 @ 6:26 pm

Nathan: the BBC doesn't use "actress" anymore; if people don't hear it, they'll probably stop using it. "Waitress" might last longer but there are efforts to get us to say "server" instead.

As far as "stewardess" is concerned, I still use it, but I'm 43, so that puts me in the old fogeys group…

Frederic said,

August 16, 2010 @ 6:36 pm

J. W. Brewer said:

It's interesting to note that there's no English noun parallel for poetess for novel-writer (although I guess the phrase "lady novelist" is an imperfect parallel?).

And why not using "novelist" for a female writer by default and "male novelist" for a man?

In French, words that are coming from the Latin and neutral in Latin, "ministre" for example, are always masculine, since the neutral doesn't exist. But it's also because for words such as "ministre" or "maire", mayor, it's the function that is specified and not the individual. Nevertheless I totally support the use of "le" or "la" when possible since those words don't even have to be "feminized" as they end with the letter "e"', which usually ends feminine words….like "poete" by the way…

Will said,

August 16, 2010 @ 6:42 pm

In English, these "male" forms (poet, priest, etc) are perceived as neuter; female forms thus are "marked". Especially since a lot of words (I.e. Novelist, writer) have no gendered forms at all.

In the romance languages every word has a gender, there's no neuter option. So a feminine form of a word is not more marked than the masculine form. And the masculine form is definiitely masculine and not gender-neutral. Even in English, you don't see the feminists clamoring to be called anchormen and chairmen–they would prefer a feminine form to an exclusively masculine one.

Paul Clapham said,

August 16, 2010 @ 6:49 pm

I'm surprised that Fisk took French as the object of his desire. But perhaps taking, say, the Slavic languages to symbolize the segregation of the sexes wouldn't have seemed as classy, or something.

I'm just reading up on Slovene, and from what I can see every occupation has male and female forms. Teachers, lawyers… although my dictionary doesn't tell me the word for "stripper". Even the word for "friend" comes in obligatory male and female forms.

Although no doubt I'm getting the simplified version from my beginner book and this distinction is starting to erode there too; wouldn't surprise me.

Xmun said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:00 pm

Here in NZ it's become customary to lose the "men" bit: we speak of "anchor" and "chair" (people, that is, both of them). Also of "poet", "priest", etc., referring to either a man or a woman.

Karen said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:06 pm

In Russian, at least, the so-called feminine forms (like doktorsha) originally meant "wife-of-the-doctor". They were coopted when women started doing the jobs and now are beginning to fade. Mehr, mayor, has no feminine form, for instance, and if the mayor's a woman, you know it by the verbs and adjectives (which are feminine). Just as you do with the so-called common gender nouns, which are feminine in form but take masculine adjectives and verbs when referring to males (sirota, orphan). So, yeah, the form of the noun is not the only way to mark the gender, which definitely gets marked.

Anna said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:19 pm

Forgive me if this is slightly off topic, but ever since I read Hedi's post, I've been wondering how people who speak languages with grammatical gender for nouns think of those nouns.

If the grammatical terminology "passive voice" leads [some] English speakers to assume that using the passive is a mark of "wimpy" or "weaselly" writing, how does referring to a system of correlated sound changes as "masculine" or "feminine" affect the perception of the underlying words?

When I learned German, my fellow students and I made many unkind jokes about the national character of a people who thought spoons were male, forks were female and knives were neuter. now I wonder "do they really"?

Chris Ozog said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:20 pm

"At least, I guess feminism was the start of it all, for was it not in the Eighties and early Nineties that newspapers started turning feminine nouns into male nouns?"

I think the above displays the problem quite clearly. What exactly is a "male noun"? In grammar terms, that should be a masculine noun; in biological terms, yes, the person would be male; in human gender terms, it would be, well, you make up your own mind on that one.

I actually went to the doctor's this very morning and was prescribed some penicillin by a doctor. A 'female doctor'. Yet, I have no need to qualify that with a pre-modifying "female" as the biological sex of the doctor is of no relevance to me or my story. I am also a teacher. And I am male. Are my female colleagues to become teacheresses? Or, wait, was teacher actually a female (or feminine, I don't actually know what he means) profession – think of the number of books/articles etc in which sentences such as "the teacher prepares the class and then she talks…". She? – and has become male, or masculine, or oh whatever.

Lastly, to compare with a Romance langauge is a sophism. These are grammatically gendered languages, while English (as has been said above) gave up with things like gender and cases years and years ago. If he's going to go on this line of argument, he might as well try explaining the changing gender (not sex) of the sea between Spain and France (in normal common speech, not any sort of poetic writing), for example. It's just not a valid comparison. And the point about war in the article is what exactly?

Right, that's enough for now.

Mr Punch said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:34 pm

Chairman/chairwoman/chair (@ Xmun) is the most interesting case, I think. "Chairwoman" is pretty much out, but "Madame chairman" always sounds odd.

Darryl Shpak said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:41 pm

The -ess endings definitely "feel" like they're disappearing…I know I've seen "actor" used for females many times. My internal word-acceptance-o-meter says that a female actor is fine, but a female waiter is a little odd…not unacceptable, but "waitress" is the right word in my usage. And "stewardess" is an interesting case, because while it's clearly marked as a female noun, I can't begin to imagine using the word "steward" for a male in that role. Maybe I've read too much fantasy fiction in my life, but "steward" and "stewardess" don't feel synonymous to me in the way that "actor" and "actress" do.

Rubrick said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:46 pm

Anna: Lera Boroditsky and Lauren Schmidt researched this very question (as, I imagine, have others; I just happened to know about this particular set of studies, being friends with one of the researchesses in question.)

Xmun said,

August 16, 2010 @ 7:58 pm

@Anna

Of course Germans don't think spoons are male, forks female, and knives neuter. Just as they don't think a "Mädchen" is neuter. Biological sex and grammatical gender are two utterly different things, despite the many cases where they happen to agree.

empty said,

August 16, 2010 @ 8:00 pm

I actually heard someone say "steward" the other day, taking about a male flight attendant. Never heard that before. Me, I always think "stewardess" but say "flight attendant. (I am 56.)

exackerly said,

August 16, 2010 @ 9:08 pm

"Waitress" is already on the way out, hasn't anybody been listening? "Hi, I'm Bethany and I'll be your server tonight."

But I think "servix" would be a variant worth suggesting…

Xmun said,

August 16, 2010 @ 9:58 pm

Despite or because of the pun with "cervix"?

The usual word for a female servant was "ancilla".

bloix said,

August 16, 2010 @ 10:24 pm

"including adding the "wo" to "man" to show this outsidedness. ""

The etymology of "woman" is well-studied, and the word does not result from adding wo- to man. In my unexpert understanding, the history is this: in early Old English, the word for woman was "wif," and the word for man was "wer." The word "man" or "mon" meant an adult of either sex. In Old English, a married couple was "wif and wer" or "wifman and werman."

"Wifman" evolved into woman, "wif" into wife, and "man" as a generic term became limited to males. "Wer" became obsolete, persisting only in "werewolf" and in historical terms like "wergeld."

Faith said,

August 17, 2010 @ 12:57 am

My personal peeve is "Jewess." It's enough that Jewish women aren't considered equal in religious terms, but we should at least be acknowledged to be Jews. And I note even Fisk did not attempt to defend "Jewess."

Reinhold {Rey} Aman said,

August 17, 2010 @ 2:38 am

@ Anna:

When I learned German, my fellow students and I made many unkind jokes about the national character of a people who thought spoons were male, forks were female and knives were neuter. now I wonder "do they really"?

Wonder no more, dear Anna: we sex-obsessed native speakers of German really see tiny penes-cum-scrota and vulvae attached to all masculine and feminine nouns.

And speaking of genitalia: Would you also make unkind jokes about the national character of the confused Spanish-speakers, who think the penis is "female" (la verga), or the even more confused French-speakers, who also think that the penis is "female" (la bite) and worse, that the vagina is "male" (le vagin)?

Jair said,

August 17, 2010 @ 3:07 am

I also thought of "Jewess". Is that term even used now? The only place I've encountered it is in Ivanhoe. It seems a bit offensive to me, but I'm not sure why. Perhaps it seems a bit beastly, reminding me of "tigress". Mostly it just seems archaic.

Peter Corbett said,

August 17, 2010 @ 4:47 am

To my ears, the word "priestess" would sound strange when applied to a modern Christian female minister, whereas "female priest" would sound strange in an ancient pagan context, especially in those cases where being female was part of the job description.

Similarly, some people in this thread mention "actress" as a likely holdout – given the current taste that in general prefers male actors for male characters and female actors for female characters, it seems that an actor/actress distinction has more to it than a poet/poetess distinction does. That said, I'm not sure which word I'd naturally use for a woman who acts were it to come up naturally in conversation (and not on a discussion of gendered nouns), so I wouldn't be entirely surprised to see that distinction die out.

Alon Lischinsky said,

August 17, 2010 @ 4:52 am

@Leonardo Herrera:

Well, that depends on your dialect, age and a number of other preferences. "Actriz" is still very much the norm, but "poetisa" has a long and complex history.

Briefly put, back in the 15th century, Nebrija regarded "poeta" as epicene. "Poetisa" is first attested in the 17th century, and never displaced the earlier term. At the same time Quevedo was using the marked feminine form, Lope de Vega stuck to "poeta", and it wasn't merely an idiosyncratic choice: Rosalía de Castro, two centuries later, used "poeta" to describe Madame de Staël. There is a very good piece on the topic by Soledad de Andrés Castellanos here.

Regarding "presidente"/"presidenta", I posted several links to academic discussions of the topic in this earlier thread (scroll down for a further comment with more data).

Adrian Bailey said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:08 am

Grammatical gender: when children learn to speak, there isn't any discussion of grammar, they just copy people saying "sur la table" and "sur le plancher" and get used to it. When English speakers learn French there is some confusion at first over nouns being either "masculine" or "feminine" but they get over it once they realise this is nomenclature. But it's more useful giving them these names than just gender A and gender B, and more natural because of their use with père, mère, etc.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:27 am

@Anna, Xmun, R. Aman: Have a look at that article linked by Rubrick. Most of the time, grammatical gender and biological sex may be two different things. But there are quite a few contexts where they aren't, really.

Think, for example, of how inanimate objects are anthropomorphised in literature etc. For example, these days, quite a proportion of children's cartoons on Polish TV are translated from English, and from time to time you see an object anthropomorphised against its grammatical gender in Polish. Always slightly jarring. I'd have to talk to my nephew (or his mother) to get specific examples, but if you — say — make an onion male, it/he will have to be referred to as "Mr Onion" in the Polish translation. Without overt specification, an anthropomorphised "Onion" is always female in Polish. Etc., etc. (Cf. the name/object associations in that article.)

So, Xmun, in a children's story, is a fork male or female? It will be evidently male in Polish ;)

Breffni said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:34 am

Fisk asks:

Slightly ironic choice of example, since seamster was originally (Old English) feminine, as was the suffix -ster in general. So it's not quite true that, as Fisk puts it, "'twas never the other way round", if he means we don't find shifts from feminine to masculine.

Breffni said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:49 am

Jarek, that reminds me of Shaun the Sheep, who in Spanish is La Oveja Shaun. As far as I can tell, the character remains male in the Spanish version (there's no dialogue so it's hard to be sure), but the theme song goes "La oveja Shaun / será tu amiga aunque no sepas balar". I'm told that's obligatory, i.e., the gender mismatch between "la oveja" and "un amigo" doesn't work; it's odd, if not outright wrong.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 17, 2010 @ 8:06 am

@Breffni: Well, Shaun is marketed in Poland as Baranek Shaun 'the little ram/lamb Shaun', and baranek is masculine, as you would imagine. This circumvents this specific problem. And with animals (at least higher order animals) there is usually some choice of sex/gender-specific terms. That's why I think it's more interesting to look at onions and forks ;)

But, yes, the principle is the same.

BTW, ram/lamb, what a cute minimal pair. Hard to believe I never noticed it before.

army1987 said,

August 17, 2010 @ 8:59 am

The tortoise in Gödel, Escher, Bach by Hofstadter became female in the Italian and French translation to avoid a mismatch with the grammatical gender of tartaruga. (BTW, for some reason tortoise suggests maleness and turtle suggests femaleness to me; can anyone make any reasonable hypothesis of why? The Pokémon names Squirtle, Wartortle and Blastoise might have something to do with that.)

Ben Hemmens said,

August 17, 2010 @ 12:22 pm

It's kind of amusing that emancipation in English has taken the route of removing "female" endings, whereas in German, political correctness requires the new, neutral ending -In., as in SchauspielerIn for Schauspieler und/oder Schauspielerin (actor).

Who else uses an uppercase letter within words?

Steve Harris said,

August 17, 2010 @ 12:52 pm

Regarding gendered terms of address:

As I recall, in one of the "Star Trek" series ("Next Generation", I think), a female officer is always addressed as "Sir" while in another ("Voyager", I believe), the required form of address to a female officer is "Ma'am". Perhaps, though it was up to the preferences of the officer in question. Just fiction—but it made a political point to me, that these things matter to people (if to no one else, to the authors of the series).

Fiction aside: What is the state of gendered address in the military forces of today?

Ken Brown said,

August 17, 2010 @ 1:45 pm

Do any of those translations of "Shaun the Sheep" preserve the English pun? Or do they (like the translations of Asterix into English) introduce equivalent ones in other languages?

Vita Sackville-West is almost certainly best known as neither a novelist nor a poet but as a gardener. At least in Britain among the Radio-4-listening, late-night-digital-TV-watching, Guardian-reading classes.

In the Church of England to call a woman priest a "priestess" is fighting talk. It can be seriously offensive, and would almost certainly be intended to offend.

Though the kind of Anglican who might address a male priest "father" has the interesting choice of whether to call women priests "mother" (which I have heard) or even "father" (which I have also heard, but much less often) Probably aonly a minority of the CofE would call priests "Father", its a strong marker for Anglo-Catholic tendencies – I understand that its more common and less marked among US Episcopalians.

Bloix said,

August 17, 2010 @ 2:37 pm

Steve Harris – you may recall the incident a year ago when a general (Brig General Michael Walsh of the Army Corps of Engineers), while testifying before a Senate Commitee, called Senatorr Boxer "ma'am." She called him out on it, saying, "would you please address me as 'Senator,' I've worked hard for this title." But the general was using the standard form of address in the military for a female officer senior to the speaker.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 17, 2010 @ 2:45 pm

@Ken Brown: Do any of those translations of "Shaun the Sheep" preserve the English pun?

Well, the Polish translation doesn't. But I suspect that, out of context, the pun may be opaque to people who are not speakers of non-rhotic English, even to Americans, not to mentioned the pesky foreigners; those would need some knowledge of the story to (possibly) get it. And judging by the fate of other film titles in Poland, I wouldn't be suprised if the person who chose the title had no idea whatsoever of what the pun is and why it is there.

Xmun said,

August 17, 2010 @ 3:36 pm

@Ben Hemmens: Who else uses an uppercase letter within words?

You see it in Irish, but as I don't know the language I can't explain how it comes about. I imagine that what precedes the capital letter is a proclitic preposition or something of the sort.

Of course it's commonplace in commercial names, e.g. TypeHouse (a typesetting firm I used to have dealings with).

[(myl) See CamelCase.]

Debbie said,

August 17, 2010 @ 3:54 pm

Steve Harris: regarding your reference to STV, I wondered about pop culture and its influence on words that denote gender in Geoff Nunberg's's post, The Twilight of 'S' (Language Log Aug. 17). As for priest/ess, isn't priestess used in Wiccan?

I also read several blogs by authors and writer/novelists/author are all used without gender specifications unless it's relevant in which case the word female/male is specified before the pronoun.

blahedo said,

August 17, 2010 @ 4:20 pm

Regarding "priest" and "priestess", there's a lot more going on than just the -ess ending. As @Ken points out above, Christian denominations with female priests never use the term "priestess". Conversely, several neopagan groups will often use "priestess" as an epicene form for their own clergy—who are often female, but because of the long antagonism by Christians, even the males prefer the pagan connotations of "priestess".

maidhc said,

August 17, 2010 @ 5:09 pm

Xmun: In Irish the initial consonant of a word may change according to grammatical context. "cloch"=stone, "ar an gcloch"=on the stone. The first letter is the pronunciation, the second is the original. If the first letter is capitalized, the spelling convention is to retain the original capital, e.g. "Gaillimh"=Galway, "i nGaillimh"=in Galway.

Irish has a "feminine of reference", so that certain nouns of masculine gender are referred to by a feminine pronoun. Ó Siadhail lists modes of conveyance, machines, containers, certain animals, certain garments and books. This can also be found in some dialects of English, possibly influenced by Irish. For example, engines are feminine: "Start her up", "She's running better now".

Breffni said,

August 17, 2010 @ 5:10 pm

Xmun: non-initial capitals in Irish are due to initial consonant mutations rather than proclitics. The internal capital only occur if the affected word happens to be a proper noun.

Ben said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:48 pm

In some of these pairs, the words really do have different meanings beyond the sex of the referent (that is, different denotations, not just potential condescending connotations). Two such pairs were already discussed above — "Steward / Stewardess" and "Priest / Priestess". Another one that immediately comes to mind is "Master / Mistress". I'm sure there are others as well.

I've never heard the term stewardess used in real life (I've only ever heard and only ever use "flight attendant" for either sex), but in movies and the such it only means "female flight attendant" and almost never (entirely never?) means "female in charge of something". On the other hand steward usually means "someone in charge of something" (not necessarily a male in charge of something), and almost never means "male flight attendant".

And "priestess" almost always refers to a particular religious role that cannot be occupied by men, whereas "priest" refers to a completely different particular religious role that until recently could not be occupied by women.

Then there are the cases where the difference (beside sex) is primarily in connotation, but the derogatory connotation is very strong — especially with words like doctress and authoress, but also with words like poetess. And the "-ess" suffix, while it can apply archaically to a lot of professions, really isn't productive. Try applying it to new professions and it's not so much condescending as just comical — consider "astronautess" or "computer programress".

And I'm not even sure how to categorize words like "temptress" and "dominatrix" that don't even seem to even have male forms (tempter and dominator are only tangentially related semantically). Obviously you could come up with male terms to fit these roles — like dominatrix vs. master, but such words are formally unrelated.

Finally, there are few pairs where the female form has absolutely no derogatory connotations — in my mind at least, but I suspect generally — and only denotes the sex of the referent. "Actor / actress", "waiter / waitress", and "host / hostess" are the only three such pairs I can think of offhand, but there might be others. And the moves from "actor/actress" to "actor" and "waiter/waitress" to "server" are both gaining momentum (and some press), and I suspect that there is a movement from "hostess" to "host" as well. Of these pairs, I think "waiter/waitress" will survive the longest. I think this is because "waiter" is more strongly marked for maleness than "actor" or "host", as evidenced by the fact that only "waiter/waitress" is moving to a completely new term (server) rather than moving to the non-suffixed form.

Ben said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:51 pm

Regarding inter-word capitals, the first thing that came to my mind was Irish names starting with "Mc" or "Mac".

Ben said,

August 17, 2010 @ 7:53 pm

Note to self: When coming back to a browser window that was left open all day, click refresh and read the new comments before posting one yourself…

Xmun said,

August 17, 2010 @ 10:04 pm

@maidhc and Breffni

Thank you for the information. Alas, it's a long time since I was last "i nGaillimh", but I remember it well, and stopping on the way to enjoy some Tullamore Dew in Tullamore.

Qov said,

August 18, 2010 @ 3:07 am

Peter Corbett, you just nailed it with "Especially in those cases where being female was part of the job description." That is exactly the only time when a feminine form is needed.

Ben Hemmens, Klingon uses uppercase within words, but that's a matter of alphabet not word-forming. In a word like QoQqoq, the Q is a completely different sound than the q, just arbitrarily chosen symbols to make the language possible to type on widely available keyboards.

Ken Brown said,

August 18, 2010 @ 7:46 am

Not sure "host" and "hostess" are exactly equivalent in current usage. A "host" is the person who presides over some social event, or whose house is being used by others, and can be either sex. A "hostess" can be a female one of those, but it can also be a prostitute, or near-prostitute, someone whose company is available for drinks or money – the male equivalent to that would not be a "host" but an "escort". And (perhaps historically) it is a rich or famous woman in the habit of holding parties with interesting guests.

Apropos of nothing, as far as I know all three senses of the word "host" – someone who makes people welcome, consecrated bread eaten at Holy Communion, an army or large crowd – and also "hostile", share an etymological origin with each other *and* with the word "guest". Which just goes to show. Something or other.

vanya said,

August 18, 2010 @ 10:39 am

I've never heard the term stewardess used in real life

Are you serious? How old are you? I'm in my early 40s – in casual conversation "stewardess" is still the world people use, although in a business setting or where people are afraid of being offensive I hear "flight attendant." To my ears "flight attendant" still sounds like a condescending euphemism, on a par with "sanitation expert" or "maintenance engineer". I can't imagine calling a steward a flight attendant either, to me "flight attendant" clearly refers to females.

army1987 said,

August 18, 2010 @ 11:01 am

In Italian, there are at least four different ways this can be handled, depending on the noun:

1) The same grammatical gender is used, regardless of the sex of the person. (It's often but not always the one corresponding to the more common sex: soprano is masculine but guardia 'guard' is feminine.)

2) The noun is inflected for gender the normal way (i.e., the same way as you'd inflect an adjective rhyming with it): e.g. il maestro, la maestra;

3) The feminine is obtained by adding a suffix to the masculine (e.g. il dottore, la dottoressa) or vice versa (e.g. lo stregone 'the sorcerer', la strega 'the sorceress')

4) Entirely different roots are used.

In many cases (including all the example I gave) one of the options is well established, to the point that any other one would be taken to be sarcastic; but for many nouns several are possible, and the trend appears to be away from 3 and towards 1. The one I prefer is 2, because 3 and 4 are too sexist for me, and the 1 makes for awkward agreements and dubious situations (e.g., if a person is referred both by proper name and by job title and the grammatical genders don't match, I'm not always sure whether to use feminine or masculine adjectives, and often both possibilities sound wrong to me.)

Ben said,

August 18, 2010 @ 11:54 am

@vanya

I'm in my mid-twenties. "Flight attendant" is simply the term that I hear used for that position, and it has nothing to do with "business settings" or "afraid of being offensive"; it's the term I learned and the term me and my friends use (not to mention the airlines). Maybe it's age-related (most of my friends are also my age), or maybe it's a regional variation (though considering the nature of the job, "regional" loses some meaning). I'd like to know what people who actually have the occupation call themselves, and see if there is also variation there.

Sorry, but that just doesn't make sense to me — I've always felt the term to be entirely epicene.

groki said,

August 18, 2010 @ 5:51 pm

another two examples of genderization:

1) in an imperfect chime with master/mistress, the feminine of bastard: bistress.

2) in the early nineties (hey, Robert), a group of us began meeting monthly for readers' theater. an evening's leader–of whichever gender–gets the honorary title dictatrix (blending dictator and dominatrix). this is partly an homage to the forceful personality of the woman who founded the group, but mostly it's a chance to play with roles, meanings, and language–which is rather the point of the group.

Richard Gadsden said,

August 19, 2010 @ 3:14 am

I never use either "flight attendant" or "steward/stewardess" but "cabin crew". That's what the captains say, and my usage follows.

Andrew (not the same one) said,

August 19, 2010 @ 2:45 pm

I have sometimes seen the boys who played female roles in Shakespeare's theatre referred to as 'boy actresses', implying that 'actress' relates to the gender of the character rather than the actor.

Stephen Jones said,

August 22, 2010 @ 2:51 pm

Poetisa in Catalan is even more demeaning than poetess in English, so Fisk's comment about 'actrice' is particularly stupid.

Plenty of people, including myself, insist on using 'actress' because it is one of he few jobs which are clearly distinguished by sex.

The Guardian excoriates 'actress', but allows waitress, which tells you more about the snobbism of the Guardianista than it does about actual English usage.

Stephen Jones said,

August 22, 2010 @ 2:55 pm

Because until recently there were very few male flight attendants.