Vocabulary display in the CNN debate

« previous post | next post »

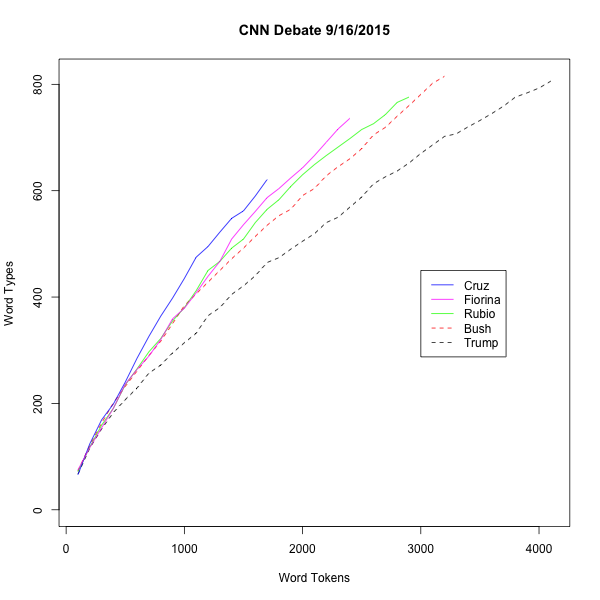

For fans of what we might call rhetoricometry — methods that let you analyze political discourse without having to listen to it or read it :-) — here's a type-token plot of the contributions to Wednesday's CNN debate of five of the eleven candidates who were featured in the prime-time round:

This plot suggests that Donald Trump's relatively low rate of lexical exhibition, noted previously in "Political vocabulary display" (9/10/2015), is a consistent feature of his rhetorical style. But higher rates of vocabulary display are generally associated with higher socio-economic status (See "Lexical bling: Vocabulary display and social status"). And The Donald is stereotypically fond of status displays. So what's up with that?

In this and other respects — more use of pronouns, less use of "the", more parentheticals and disfluencies — Trump's style is relatively informal and conversational. (See "The most Trumpish (and Bushish) words", 9/5/2015, and "Trump's eloquence", 8/5/2015.)

Maybe a clue can be found in Judith Irvine, " When Talk Isn't Cheap: Language And Political Economy." American Ethnologist 1989, which I quoted in "Status and fluency", 5/11/2004:

Among rural Wolof, skills in discourse management are essential to the role of the griot (bard), whose traditional profession involves special rhetorical and conversational duties such as persuasive speechmaking on a patron's behalf, making entertaining conversation, transmitting messages to the public, and performing the various genres of praise-singing. … High-ranking political leaders do not engage in these griot-linked forms of discourse themselves; to do so would be incompatible with their "nobility' and qualifications for office. But their ability to recruit and pay a skillful, reputable griot to speak on their behalf is essential, both to hold high position and to gain access to it in the first place.

As I noted in the cited post, "male members of the British aristocracy are also stereotypically disfluent, at least according to P.G. Wodehouse and Monty Python". (See also this further note on style and status in Wolof.)

So maybe the relationship between status and verbal facility is actually a u-shaped curve even in today's America. Maybe Donald Trump's low rates of lexical ostentation — and his sometimes divergent and apparently incoherent style of presentation — are actually his way of telling us that's he's above all that. If he needs lots of big words and complex sentences arranged in aesthetically impressive paragraphs, he can hire somebody. And it'll be great, trust him.

DWalker said,

September 18, 2015 @ 10:30 am

"analyz[ing] political discourse without having to listen to it or read it"!! What a great concept.

Thanks for the terrific thought!

_NL said,

September 18, 2015 @ 11:05 am

He reduces most concepts and propositions to simple terms: nice, good, smart, ugly, loser, dumb, etc. And even these verdicts are not always ironclad, like when he says he likes somebody then immediately contradicts himself

So I don't know that he needs a broad lexicon when he passes a simplistic judgment on all propositions and when the judgments are themselves fluid.

The other candidates want to impress you with their knowledge, their passion, their idealism, their competence, or whatever else, so they try to show off in elaborate displays. Donald just flat-out tells you he's smart and rich, and that people who don't like him are probably all ugly and dumb.

2 Things | Digital Praxis Seminar Fall 2015 – Spring 2016 said,

September 18, 2015 @ 11:12 am

[…] I love the Language Log blog and today they introduced me to a neologism that seemed relevant to our current readings: […]

Lance Nathan said,

September 18, 2015 @ 2:27 pm

My impression is that Trump is pitching himself to the working class; I wonder whether his vocabulary would be any different when speaking to other millionaires. The recent Rolling Stone profile, for instance (http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/trump-seriously-20150909) has lines line

and

I don't know about their syntax, but Solotaroff may have been onto something in terms of his word usage.

[(myl) You're right that there might be some inverse prestige involved.]

Simon Spero said,

September 18, 2015 @ 2:39 pm

It seems dangerous to embark on a quantitative study of rhetoric without concern for the history of the study of rhetoric- surely the path to epistrophe.

It seems dangerous to embark on such a study without proper consideration of rhetorical devices such as anaphora.

At a time when the triangle stands as a symbol of equality, can we let the polysemy and the tyranny of Metrics be shaped into a wedge to make it symbol of inequality?

And can we ignore the discourse context in which each utterance was made?

The event was Sui genre, and allowed candidates to respond if they were mentioned by name by another candidate. These response cascades would often drift away from the original topic, and into recitations of stump speeches.

A candidate given few opportunities to speaks, but a more diverse set of topics would likely have a higher TTR than one whose utterances were focused on fewer topics. The silence of the Donald during the more policy intensive portions of the event reduced his opportunities to shine.

Cruz spoke had relatively few opportunities to speak, and may have used more rote content, which would have boosted his TTR, but having a background in formal debates, might have a deflated TTR from the use of rhetorical devices.

Fiorina covered a lot of topics in depth, but also made effective use of rhetorical repetition.

In other words, TTR is probably not a good metric for this application. Controlling for extended overlaps with stump speeches, for rhetorical devices, and for words or lemmata used by an earlier speaker might be more informative.

Also, Carson may be hurt if "[inaudible]" is treated as a single type.

Bob Ladd said,

September 18, 2015 @ 4:14 pm

Is the secondary stress in rhetoricometry on rhe- or -tor-?

D.O. said,

September 18, 2015 @ 7:31 pm

Apparently, Prof. Liberman is not going to discuss most distinguishing words for each of the participants of the latest Republican debates, so I took it upon myself to make a dinner-time experiment. My tool of choice is z-score for every uttered token, which usually is almost exactly the same in ranking the high-end results as Prof. Liberman's preferred pseudo-Bayesian measure. Results are nothing short of spectacular. Here's are the most z-scoring words

Bush — strategy

Carson — recognize

Christie — playing

Cruz — court

Fiorina — nation

Huckabee — cancer

Kasich — incumbent

Paul — war

Rubio — cannot

Trump — I

Walker — education

Now, the smallest z-scores, that is the words a speaker dis-prefers compared to others

Bush — who

Carson — for

Christie — a

Cruz — people

Fiorina — 'm

Huckabee — so

Kasich — he

Paul — this

Rubio — n't

Trump — the

Walker — have

Meh. The most we can learn from the second list is that Sen. Rubio does not like n't contraction very much.

Now, let's look at unique words. Here's the list of words that the speaker used but nobody else. I selected only the most frequent such word for each speaker (counts in parentheses)

Bush — strategy (7)

Carson — logical (3)

Christie — playing (5)

Cruz — appointed (5)

Fiorina — track (7)

Huckabee — cancer (3)

Kasich — incumbent (5)

Paul — response (6)

Rubio — fly (5)

Trump — disaster (6)

Walker — restrictions (3)

A bit strange that it does not coincide with the first list, given that the first one is not populated by high-frequency words…

And now the choicest information, the words the speaker didn't say even once though others were using them a lot

Bush — Jake (50)

Carson — 'll (63)

Christie — great (45)

Cruz — going (91)

Fiorina — 'm (120)

Huckabee — many (34)

Kasich — like (54)

Paul — just (81)

Rubio — she (55)

Trump — America (63)

Walker — she (55)

I'm not making this up, at worst I made a coding mistake. Of course, my scripts count the variations like America, American, Americans as different (sucks), but Trump didn't utter two latter words as well.

[(myl) Neat! ]

D.O. said,

September 18, 2015 @ 8:24 pm

As for vocabulary display, judging by perplexity Ms. Fiorina edged out Sen. Cruz (318 vs. 311) . At the lower end, Gov. Walker (242) beat Gov. Huckabee (251) and Dr. Carson (254) . Mr. Trump (281) was dead average. Maybe, because word-frequency distribution is fat-tailed, one needs to adjust for the total words spoken, though…

Jeff B. said,

September 19, 2015 @ 12:51 am

Thank god we don't elect our politicians based on linguistics. Though Orwell might have loved this type of analysis, it is meaningless and irresponsible (much like Orwell'sopen writings).

Geoff Nunberg said,

September 19, 2015 @ 9:06 am

I think Trump is playing a different game here — it's not really public speaking at all. As I wrote in a piece in the LA Times a couple of weeks ago:

But if Trump is a bloviator, he's one who regards words with something between indifference and disdain. He'd never overreach for a fancy word and come up with something like George W. Bush's "Grecians" or Sarah Palin's "refudiate." He's utterly unself-conscious about his language, and if he has any self-awareness about it, he does a good job of hiding it. The broken sentences, repetitions, false starts and digressions, the banal superlatives and insults —Tremendous! Fabulous! Moron! Loser! — Trump may be sui generis as a candidate, but his language is the culmination of a fixation with the "natural" that has shaped public discourse over the last century. It's not really public speaking, just a simulation of street-corner schmoozing, which is one reason so many people find Trump "real," "authentic" and even "just like us."

And yet. The bloviator's first object is to dazzle himself with his own words, and Trump's are exactly the simple ones that he wants to hear, particularly when the conversation turns to his favorite subject: "I'm really rich." "I'm a really smart guy."

I think of what the psychologist B.F. Skinner said: The reason we boast is to hear someone saying nice things about us.

Of course, this was before Trump came up with "braggadocious."