The genitive of lifeless things

« previous post | next post »

I've heard many interesting papers here at AACL 2009. Here's one of them: Bridget Jankowski, from the University of Toronto, "Grammatical and register variation and change: A multi-corpora perspective on the English genitive". She was kind enough to send me a copy of her slides, from which I've taken (most of) the graphs below.

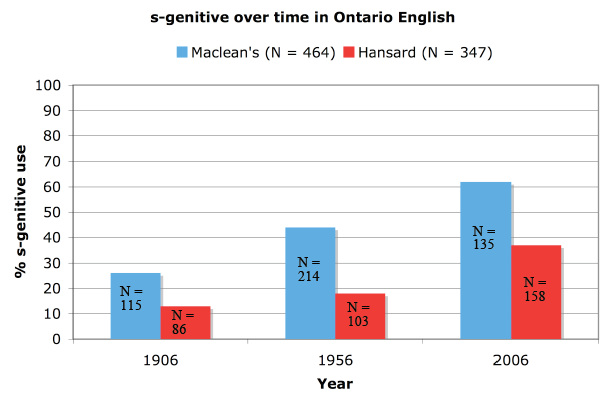

In order to study the history of choices like "Ontario's government" (s-genitive) vs. "the government of Ontario" (of-genitive), she created two small historical corpora, sampling Maclean's magazine and the Hansard transcripts of debates of the Ontario Provincial Legislature at three time points: 1906, 1956, and 2006. She picked three authors or three speakers from each source at each time point. All of the speakers and authors were men aged 30-60 at the time of the sample.

Her first result is a replication of the observation that the s-genitive has been gaining ground:

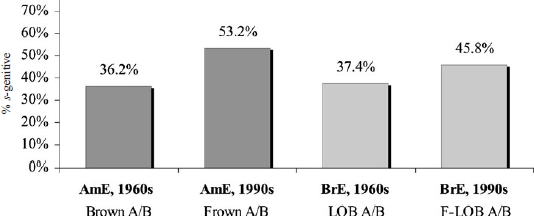

Compare, for example, this figure from Hinrichs and Szmrecsanyi, "Recent changes in the function and frequency of standard English genitive constructions: a multivariate analysis of tagged corpora", English Language and Linguistics 11(3): 437–474, 2007:

Jankowski then broke the trends down further by coding the possessors as

- Human: a student’s schoolwork, Mrs. Hale’s reaction

- Organizations (animate “collectivities of humans which display some degree of groupidentity”): the local school board’s ruling; the federal government’s plan

- Places: Canada’s foreign language press, Ontario’s roads, the streets of Rome, the raw edge of the world, the people of this American continent

- Inanimate objects, activities, units of time, states

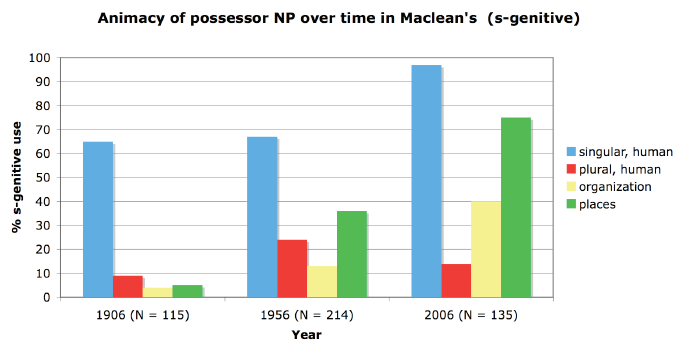

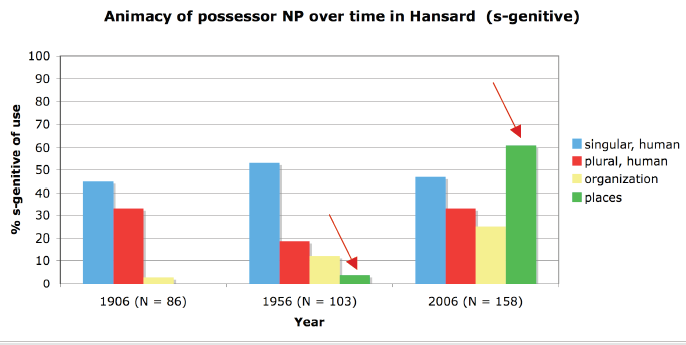

This made it clear that the increase in use of s-genitives has been especially strong in the case of organizations, and even stronger in the case of places:

Her category 4 ("Inanimate objects, activities, units of time, states") was realized overall with of-genitive 96% in Maclean’s and 99% in Hansard. So her results are generally consistent with Otto Jespersen's observation in A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles: Part VII (1949) that

In poetry and in higher literary style, the genitive of lifeless things is used in many cases where of would be used in ordinary speech. […] During the last few years the genitive of lifeless things has been gaining ground, (especially among journalists)…

but only if "lifeless things" is taken to include organizations and places, and not "inanimate objects, activities, units of time, states".

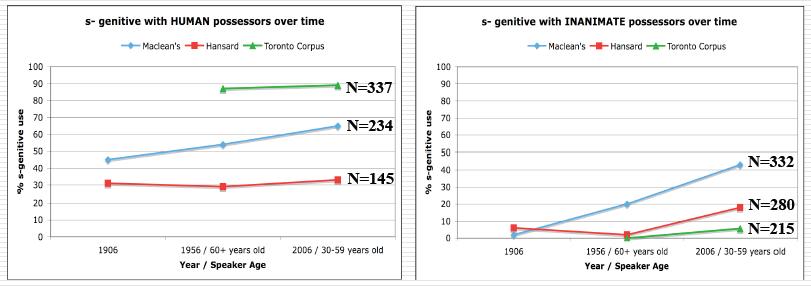

She also compared her results to data from a corpus of conversational speech collected recently in Toronto, using speaker age to create two "apparent time" collections comparable to the 1956 and 2006 samples. This suggests that in the spoken language, human possessors have almost always gotten the s-genitive, consistently across time, while inanimate possessors (in this graph including her categories 3 and 4) have consistently gotten the of-genitive:

On this analysis, the increase in s-genitives for human possessors in Maclean's magazine makes the journalistic prose more and more like the spoken language; but the parallel increase in s-genitives for inaminate possessors makes the journalistic prose less and less speech-like.

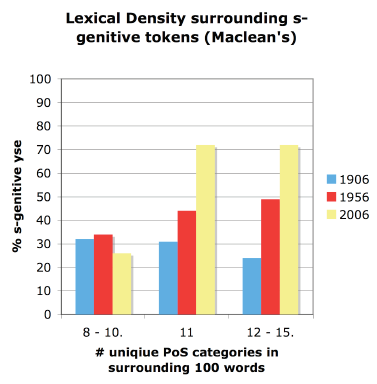

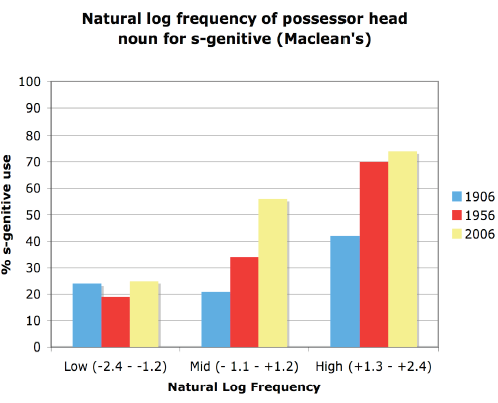

Her presentation also considered the effect of the length of the possessor (a shorter possessor is more likely to take an s-genitive) and the possessum ("shorter possessum will be more likely to take an of-genitive and so appear first in the construction, while a longer possessum is more likely to take the s-genitive"), as well as other relevant features such as "lexical density":

and "thematicity":

and did a multivariate analysis of all the various factors taken together.

You'll have to read her (I trust forthcoming) paper to learn how it all comes out — I have a 6:40 a.m. plane to catch — but I hope that this much is enough to convince you that there's a rich and interesting pattern of variation to be untangled here. It certainly convinced me.

And it also increased my general feeling that the time is right for the application of automatic or semi-automatic methods of analysis (here in assigning her four categories of possessors, in determining the lengths of the possessor and possessum constituents, in counting local phrases co-referential with the possessor, etc.) to the study of syntactic variation across time, genre, register and so on. Because she had to annotate everything by hand, Jankowski's sample was fairly small — 50K words of Maclean's, and 100K words of Hansards. With automatic or semi-automatic annotation, she could look at larger collections with denser time samples of more sources, and easily add other features, like various word and phrase frequencies, grammatical role and phrasal position of the whole genitive construction, etc.

Dave Bath said,

October 11, 2009 @ 6:40 am

I wonder if there is something that could detect sensitivity to "ugly" s-genitives, where things that are already plural or end in "S" are more likely to to be given "of" because the s-genitive is awkward in speech or print. I try to avoid plurals' s-genitives.

So… what about "horn of the rhinoceros", "sounds of geese", "properties of gneiss", "reliability of sources" and the like? Do others use "of" more often in these cases than in non-s-ending words?

Lazar said,

October 11, 2009 @ 7:02 am

Some applications of the s-genitive to lifeless things (or perhaps I should say abstract things) really rub me the wrong way. For example, a while ago there were these advocacy ads (in support of nurses) by a group called "The Campaign for Nursing's Future", and the application of the s-genitive to the abstract noun "nursing" struck me the same way that "moist" strikes some folks.

Another example that I came across on Wikipedia recently, discussing the phenomenon of blackface:

"Blackface's groundbreaking appropriation, exploitation, and assimilation of African-American culture… were but a prologue to the lucrative packaging, marketing, and dissemination of African-American cultural expression and its myriad derivative forms in today's world popular culture."

The s-genitive there provoked a gag-like word aversion response in me.

Spell Me Jeff said,

October 11, 2009 @ 9:41 am

I once had a science professor (ca. 1981) whose pet peeve was the use of "whose" for lifeless referents. Examples of this usage's utility are legion.

"Usage's utility" — now there's an ugly genitive

mgh said,

October 11, 2009 @ 10:37 am

it seems that a phrase like "the laws of Boston" would be more likely to change to "Boston laws" than "Boston's laws" (at least, by me).

so, do you know whether the increase in "s-genitives" accounted for all the decrease in "of-genitives," or was there also replacement by other forms?

this is not to criticize her point, in fact it would suggest the data shown above actually underestimate the strength of the phenomenon.

[(myl) Law seems to be one the nouns that sometimes takes a complement in "of". Thus it's just a mistake to replace "the law of privacy" with "privacy's law", because the "of" in question isn't really the same "of", or at least is not used in the same way.

But "the law of PLACE" → "PLACE's law" seems to me to work, even though it may be avoided for the other reasons under discussion. And in fact, it's not hard to find real examples, as in this passage from the recent NYT:

]

Dan Lufkin said,

October 11, 2009 @ 11:03 am

I often review and edit translations into English from the other Germanic languages and have noticed that overuse of the 's genitive is a reliable way to spot that the translation was done by someone for whom English is a second language, however fluent.

Another indicator is getting the order of adjectives wrong: *an Asian pretty girl. I know about the Royal Order of Adjectives, but this is a function that native speakers do on the fly without giving it a thought and it has nothing to do with syntax. (I think.)

army1987 said,

October 11, 2009 @ 11:44 am

I am Italian, and once upon a time I wrote "Church's power" in an English classwork. My teacher corrected that to "the power of the Church", and when I pointed her out that my book used "Church's power" too, she answered something like "but "the power of the Church" sounds better". (Or was that the other way round?)

Peter Taylor said,

October 11, 2009 @ 12:06 pm

I had a similar thought to mgh but about "the streets of Rome": I wouldn't be surprised to see that replaced by "Roman streets".

Ray Girvan said,

October 11, 2009 @ 12:32 pm

army1987: My teacher corrected that to "the power of the Church"

As is usual with this kind of thing, a skim of Google Books – "Church's power" – shows it to be absolutely fine, and it crops up in many theological works.

Michael Farris said,

October 11, 2009 @ 12:44 pm

When I do editing work on materials written by non-natives, I sometime's change constructions like "the church's power" to "the power of the church" (or vice versa).

Usually my motivation is euphonic, one or the other sounds or reads better (according to my aesthetic intuitions) than the other in that particular sentence. If pressed to be more specific, I say there are usually rhythmic reasons (though I can't define or describe them any better). If the sentence is changed further it might go back again.

I realise that many writers don't care about that kind of euphony (and many that do will disagree with my judgments) but that is what very often conditions my choice between an 'of' construction and something else (whether compound, genitive or adjective construction).

John Cowan said,

October 11, 2009 @ 1:21 pm

I think that New York's law is perspicuous when referring to a specific law (city ordinance), as in this case; but when speaking of the law en masse, it doesn't work.

In fact, I don't quite know how to speak of the law that is in force in Chicago en masse: Illinois law is fine, since Illinois is a sovereign jurisdiction, but Chicago law sounds bizarre, and New York law would definitely be that of the state rather than the city of New York. I'd have to fall back to the law in Chicago or the law in New York City.

Janice Huth Byer said,

October 11, 2009 @ 1:59 pm

Context allowing, my sense of place names with s-genitives is as metonyms for denizens. Ontario's government, for example, evokes a sense of government of the people of Ontario. In contrast, the government of Ontario makes me think of the government of the province of Ontario.

I suspect my pea-brain is influenced by place names like the People's Republic of China.

Jeff DeMarco said,

October 11, 2009 @ 3:53 pm

Thinking about "Roman streets" as opposed to "the streets of Rome," it strikes me as there is a higher level of formality associated with the latter that ties in with the euphony aspect of the expression. Respighi's "The Pines of Rome" and "The Fountains of Rome" would not carry the same emotional impact as "Roman Pines" or "Roman Fountains."

marie-lucie said,

October 11, 2009 @ 4:52 pm

The genitive suffix, which can correspond to "of" in some contexts, is being equated with it in more and more contexts. As a result, more and more entities are being treated as "possessors", or at least having a definite relationship with, something else, in ways which often jar with the semantics, and even the syntactic derivation, of the traditional use. The examples above show that "place" has two meanings, one purely geographical, the other one referring to the population of the place. So "New York law" means the same as "the law of/in New York", the law (in general) which applies to the city or state of New York, while "New York's law" means a specific law enacted by the people of New York and therefore in a sense "belonging" to them. Similarly, Janice's example "Ontario's government" implies that "Ontario" refers to to "the people of Ontario". But "the law of piracy" can only mean "the law concerning piracy", not "piracy's law" which would mean "the law residing in, belonging to, or enacted by, piracy".

The difference between the genitive and the of-phrase is seen in cases like "Shakespeare's use of metaphor", where a noun phrase includes both a genitive specifier and a complement consisting of an of-phrase: this phrase could be rewritten as "the use of metaphor by S". Both phrases carry the same meaning as the basic sentence "Shakespears (as an active subject) used metaphor" (which some linguists would consider as the basic "underlying form" of the phrase), and there is still an understood element of active relevance in "S's use" (which cannot be interpreted here as indicating that "someone used S"). But it not really acceptable to rewrite the phrase as *"metaphor's use by S", which would imply that "metaphor" is the active element in the phrase, whereas in the corresponding sentence it is the (inactive) object. This is what makes phrases like "blackface's appropriation (etc) of black culture" (above) awkward at best, if not ill-formed, because "blackface" by itself (which could be defined in more than one way) is being considered as an active element.

In "the Church's power" as opposed to "the power of the Church", both formally and semantically appropriate in contemporary English, the phrase is not equivalent to a sentence, but it seems that the choice of one over the other is one of "pragmatic salience" residing in the element first mentioned: just as in "Shakespeare's use" we are discussing Shakespeare in general, and his active "use" in particular, in "the Church's power" the salient element is "the Church", while in "the power of the Church" the salient element is "power", as wielded by the Church. (In this instance, "the Church" refers to an entity known to be powerful, so some people might argue about salience on semantic grounds, but the same salience of the first noun would be present with any semantic elements).

mgh said,

October 11, 2009 @ 5:29 pm

Mark and John Cowan,

I used "Boston law" simply as one example where the possessor is neither an of-genitive nor an s-genitive. It seems to me there are many such possibilities, like "Persian carpet," "talk show host", etc. I'm not a linguist so please set me straight if these are not real genitives. It just seemed that there may be other ways to decrease of-genitives.

(In scientific writing there is a prescription against s-genitives and word limits discourage of-genitives, so I'm used to tuning nouns into adejectives, as in "cell communication, "virus fusion", etc.)

John, phrases like "New York City law prohibits jaywalking" or "New York law forbids genitives" sound fine to me — do they sound weird to you?

Joe Fineman said,

October 11, 2009 @ 8:08 pm

I have often marveled at the variety of ways English offers for attaching one noun to another. There is the possessive 's, the preposition "of" (and other prepositions), unchanged attributive use of the noun (as in the examples given by Messrs. Cowan), and, more often than not, one *or more* special adjectives dedicated to the noun. A king's ransom, the name of a king, a king pin, royal prerogative, regal bearing, a kingly crown. A mother's love, mother love, maternal love, motherly love. The (a) church's power, the power of the (a) church, church power, ecclesiastical power. There are usually differences in denotation or emphasis, but they seem to me often to be peculiar to the noun concerned.

Note in particular, for nouns that express the action of verbs, the contrast between what used to be called the subjective & the objective genitive: Shakespeare's use of that word, that word's use by Shakespeare. There, the distinction is made clear by the idiomatic preposition as well as by context; but sometimes context alone is decisive: "love of a mother" could be taken either way.

Eric Christopherson said,

October 11, 2009 @ 8:56 pm

The journal title Nursing Law's Regan Report has always bewildered me. It sounds to me, because of the s-genitive, like "Nursing Law" is a proper name while "Regan Report" is a type of report, rather than a proper name — this despite Regan being a name. A little googling doesn't turn up much about why it's called that, but shows that it used to be called Regan Report on Nursing Law, which sounds much more natural!

There are other journals from that publisher by the names Hospital Law's Regan Report and Medical Law's Regan Report.

Coby Lubliner said,

October 11, 2009 @ 9:14 pm

Respighi's "The Pines of Rome" and "The Fountains of Rome" would not carry the same emotional impact as "Roman Pines" or "Roman Fountains."

Well, Respighi called them I pini di Roma and Le fontane di Roma, but he also wrote Feste romane ("Roman Festivals"), so he must have had a reason for using the possessive in the former and the adjective in the latter.

There is a tendency to translate titles of musical works as literally as possible. Le nozze di Figaro is known in English as "The Marriage of Figaro," but "Figaro's Wedding" (like the German Figaros Hochzeit) would be a lot more idiomatic.

J. Goard said,

October 11, 2009 @ 10:25 pm

Looks to be a fascinating paper!

As above comments suggest, there may be a basic flaw in treating the [Y's X] and [X of Y] constructions as alternatives exhausting some particular phenomenon called "attributive possession", or "genitive construction", or what have you.

[Y's X] seems to compete with other prepositional constructions in a number of cases, such as with superlatives (1), deverbal possessees that bring a prepositional meaning along (2), and others (3).

(1) a. California's oldest church

b. the oldest church in California

c. ?? the oldest church of California

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. the detractors from Proposition 8

c. ?? the detractors of Proposition 8

(3) a. Sorry, but we can't fix your car's scratches.

b. the scratches on your car

c. ?? the scratches of your car

What I'm wondering is whether we can reasonably conclude, on the basis of changes in [Y's X]/[Y's X]+[X of Y], that there is a shift in preference toward having the reference point come first. The above charts also seem compatible with the semantically bleached of becoming dispreferred in favor of richer prepositions or other reference point constructions.

In any case, Jankowski's results are fascinating. I'll be sure to check it out.

marie-lucie said,

October 11, 2009 @ 10:54 pm

Respighi's "The Pines of Rome" and "The Fountains of Rome" would not carry the same emotional impact as "Roman Pines" or "Roman Fountains."

– Well, Respighi called them I pini di Roma and Le fontane di Roma, but he also wrote Feste romane ("Roman Festivals"), so he must have had a reason for using the possessive in the former and the adjective in the latter.

I pini/Le fontane di Roma, like "The Pines/The Fountains of Rome", are features of Rome that exist independently of its inhabitants, but Feste romane would not exist without Roman people to participate in them and to lend the festivities their particular "Roman" character. To me Roman pines would suggest a species of pine, not pine trees growing in Rome, just like a Roman galley or Roman candle are not features of Rome itself.

Le nozze di Figaro is known in English as "The Marriage of Figaro," but "Figaro's Wedding" (like the German Figaros Hochzeit) would be a lot more idiomatic.

I quite agree. In the Romance languages there is no formal equivalent to the English genitive and normally the way to translate it is with a preposition equivalent to "of". The French play on which the opera is based is called Le mariage de Figaro which can be understood as "Figaro's marriage" (the plot hinges on whether or not he can get married) and "Figaro's wedding", with "Figaro" as the first word in English since he is the central character, most concerned with the event. But the title of the opera Le nozze di Figaro "Figaro's wedding" is translated literally in French as Les noces de Figaro which can only apply to a wedding (les noces is a rather literary way of referring to a wedding, usually a grand wedding involving historical or legendary characters – "nuptials" might come close if it did not sound so pretentious for modern life – le mariage is the usual contemporary word for both "marriage" and "wedding").

marie-lucie said,

October 11, 2009 @ 10:57 pm

p.s. In the Gospels, "the wedding at Cana" = les noces de Cana – here the de links to a place, not a "possessor", but without knowing the context one could wonder whether Cana is a place or a person.

Simon Cauchi said,

October 12, 2009 @ 2:27 am

I have no access to corpora, but it surprises me that the 's genitive for inanimate things ("inanimate" is a better word here than "lifeless", surely?) should be so rare. As the report says:

Her category 4 ("Inanimate objects, activities, units of time, states") was realized overall with of-genitive 96% in Maclean’s and 99% in Hansard.

I remember working as an editor and hearing my colleagues agree among themselves that you don't have the 's genitive with inanimates, and I'd protest: hang on now, consider "the water's edge", "a hair's breadth", "the moon's phases", etc. Granted that in all likelihood it can be shown that "the edge of the water", "the breadth of a hair", "the phases of the moon", etc., are more usual, but I don't think any of the 's phrases require ungrammatical asterisks, now, do they?

[(myl) But you do have "access to corpora"! For estimating the frequency of of and 's with "inanimate objects, activities, units of time, states", you could pick a source (say this morning's newspaper) and do a count — with colored pencils on paper, if you like. Any outcome (including that there aren't very many of either kind, or that it's hard to decide how to classify examples like "the state of the British poultry and pork industry") would be a contribution. Alternatively, you could use Mark Davies' excellent web interface to several large corpora., ,where you could check the relative frequency in the BNC of (say) "of the moon" (281) and "the moon 's" (63), or "of 1990" (584) and "1990 's" (29), thus helping to support your point.

As for "the genitive of lifeless things", you'll have to find a spritualist so as to take the matter up with Otto Jespersen in the afterlife. ]

marie-lucie said,

October 12, 2009 @ 2:55 am

That's one more reason why just mentioning "inanimates" is simplistic, as if all inanimates were of the same nature. In your examples, the "possessed" noun is a part of the other noun, or something which is so closely associated with it that it is part of its definition, like "moon's phases", unlike "metaphor's use" or the like.

Graeme said,

October 12, 2009 @ 6:13 am

The (but not 'a') story of Australia, versus Australia's story? It's six of one and half a dozen of another.

But the more abstract the entity the more problems we face. The vale of tears is anything but tears' vale. Indeed such a reversal inverts the sense of possession, the sense of what is qualifying what.

Faldone said,

October 12, 2009 @ 7:10 am

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. the detractors from Proposition 8

c. ?? the detractors of Proposition 8

This strikes me as totally wrong. I would go with:

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. ?? the detractors from Proposition 8

c. the detractors of Proposition 8

or even

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. * the detractors from Proposition 8

c. the detractors of Proposition 8

2b seems, if not ungrammatical, to mean something totally different from 2a. I'm not even sure what it is supposed to mean.

Google isn't much help. 2a gets two hits not counting this LL thread and 2c gets four (but two are quotes from the same source). 2b gets only one and it is this thread.

Chris said,

October 12, 2009 @ 9:15 am

In the specific case of "Roman", I think it could apply to anything associated with the Roman Republic and/or Empire, so any place that had been a Roman colony could have Roman streets the same way it could have Roman baths or a Roman colosseum, etc. The streets of Rome are more specifically *in Rome*, not just built in a Roman style by Roman methods.

The same goes for Roman fountains — I wouldn't be surprised to see a Roman fountain in Naples, but the fountains of Rome can only be in Rome.

Bill Walderman said,

October 12, 2009 @ 11:20 am

Personally, I have no problem with the genitive of many non-animate nouns, but even after 35 years as a lawyer, I've never been able to get used to using the genitive of the name of a law, as many lawyers do.

"ERISA's fiduciary standards" (the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974)

"the '40 Act's registration requirements" (the Investment Company Act of 1940)

"section 7702(d)'s cash value corridor" (section 7702(d) of the Internal Revenue Code)

J. W. Brewer said,

October 12, 2009 @ 11:58 am

Bill, I won't claim that litigators have as good an ear for euphony as the ERISA specialists, but, e.g., "the PSLRA's heightened pleading standards" is preferable at the margin to "the heightened pleading standards of the PSLRA" if your prose is subject by court rule to total word-count limitations. I have often wondered how the drafting style of transactional/regulatory lawyers would change if they were subjected to word-count or page-count limits.

Separately, I agree that "Roman" is a bit of a red herring. "Streets of Philadelphia" may be a bit posher or middlebrow-literary-sounding than "Philadelphia's streets," but "Philadelphian streets" sounds downright odd, or fussy, or affected, and seems per Googling to be extremely rare.

Bill Walderman said,

October 12, 2009 @ 1:10 pm

J.W.: You're right–where concision is required, the genetive of statute names is a useful device where concision is required, but it also crops up in contexts where prolixity is at a premium, like law review articles.

Clarissa said,

October 12, 2009 @ 3:48 pm

Ah, fascinating! Thanks for confirming my instincts–many of my students/clients who studied EFL previously firmly believe that no inanimate/lifeless thing can take s-genitive. If I can tell them that this has been changing over the years, they'll be more likely to believe me, because they do have an inkling that their previous textbooks and teachers' knowledge are kind of outdated.

For that matter, a linguistics professor I had in the US, who received his PhD in China, had a bit of a row with the class when most of the grad students insisted that "the school's roof needs to be repaired" sounded fine–he was using this to demonstrate how you couldn't use either s-genitive or a verb like "need" with an inanimate object.

Mr Punch said,

October 12, 2009 @ 4:32 pm

On mgh's point: "Massachusetts law" (say) is a common usage, often suggesting a possible contrast with the law of other states — Massachusetts has its own legal code, and the emphasis is on the state more than the law. "Massachusetts beaches," where the state name is used as an adjective indicating location, is a somewhat looser usage, it seems to me. (Note that there is no adjectival form for Massachusetts, unlike Rome.)

What's happened lately is that Microsoft has decreed, via its spellcheck program, that (1) "Massachusetts" can't be used as an adjective , and (2) we should use instead "Massachusetts'" with an apostrophe – which I was taught was improper (though adding and pronouncing an s is problematic).

J. Goard said,

October 13, 2009 @ 2:03 am

This strikes me as totally wrong. I would go with:

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. ?? the detractors from Proposition 8

c. the detractors of Proposition 8

Interesting. There are many examples of both (b) and (c), with different reference point nominals, e.g. (all used with "some") detractors from the Holy Scriptures, detractors from the [Downing Street] memo, detractors from the Kindle; detractors of the show, detractors of the boom in the use of mobiles by young people, detractors of the IOM report. The "of" examples all seem extremely awkward to me.

So we differ. The most important point is that, although our point of divergence doesn't seem to be about the 's genitive at all, that would be the impression created if one were to examine only our respective values for [Y's detractors]/[Y's detractors]+[detractors of Y], where mine would be nearly 100% and yours presumably much lower.

Faldone said,

October 13, 2009 @ 6:38 am

This strikes me as totally wrong. I would go with:

(2) a. Proposition 8's detractors

b. ?? the detractors from Proposition 8

c. the detractors of Proposition 8

Interesting. There are many examples of both (b) and (c), with different reference point nominals, e.g. (all used with "some") detractors from the Holy Scriptures, detractors from the [Downing Street] memo, detractors from the Kindle; detractors of the show, detractors of the boom in the use of mobiles by young people, detractors of the IOM report. The "of" examples all seem extremely awkward to me.

Could this be a cross-pondian thing? I still can't even wrap my USn mind around the 'detractors from' versions. While I might not use X's detractors I don't have any problems with it. It sounds at least acceptable.

J. Goard said,

October 13, 2009 @ 7:59 pm

I come from Northern California. :-)

Irene said,

October 14, 2009 @ 4:46 pm

I am thinking of the "power of the purse" which belongs to the Legislative branch of the US government (meaning that since only Congress has the authority to appropriate funds, it can use this power to exert influence on the Executive branch). "Purse's power" doesn't make any sense in this case. So, one would use purse as an adjective, as in, Congress' purse power, which does not convey the same gravitas.

Pippa said,

March 21, 2013 @ 10:52 am

Hi,

Would you please explain to me the difference between these 3 apparantely different kinds of Genitives:

1. That spider's web in the garden is beautiful.

2. This tropical spider's web is very strong.

3. The spider's web is use to catch prey.

Thanks in advance,

Pippa (student)