Generalization and truth

« previous post | next post »

Generalization is the essence of rationality. But the ways that human languages encourage us to generalize can cause enormous damage to rational thinking, especially in combination with the natural human preference for clear and simple stories over complicated ones.

I've cited many examples involving journalists or popular authors, most recently with respect to the effects of poverty on working memory ("Betting on the poor boy: Whorf strikes back", 4/5/2009). But in fact, this is a problem that afflicts everyone, even prize-winning behavioral economists.

According Daniel Kahneman, "Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics", The American Economic Review, 93(5): 1449-1475, 2003 [revised vesion of 2002 Nobel acceptance speech]:

Ellen J. Langer et al. (1978) provided a well-known example of what she called “mindless behavior.” In her experiment, a confederate tried to cut in line at a copying machine, using various preset “excuses.” The conclusion was that statements that had the form of an unqualified request were rejected (e.g., “Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine?”), but almost any statement that had the general form of an explanation was accepted, including “Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine because I want to make copies?” The superficiality is striking.

The cited paper is Ellen Langer, Arthur Blank and Benzion Chanowitz., "The Mindlessness of Ostensibly Thoughtful Action: The Role of "Placebic" Information in Interpersonal Interaction", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(6): 635-42, 1978. I happen to have read the Langer et al. paper recently, due to interest in the history of the notion of "placebic information" (see here for what started me off). And for the same reason, I looked through a listing of the papers that cited it, to find other areas where this concept had been applied.

What I discovered was frequent misunderstanding of the 1978 paper's results, involving both a different conclusion and a strikingly overgeneralized picture of the observed effects. Kahneman 2003 was merely the most prominent of these. So as part of my on-going exploration of scientific rhetoric, today's post describes what Langer et al. 1978 actually found.

Langer et al. tell us that

The [line-cutting] study utilized a 3 X 2 factorial design in which the variables of interest were the type of information presented (request; request plus "placebic" information; request plus real information) and the amount of effort compliance entailed (small or large).

The amount-of-effort variable was a bit complicated:

When a subject approached the copier and placed the material to be copied on the machine, the subject was approached by the experimenter just before he or she deposited the money necessary to begin copying. The subject was then asked to let the experimenter use the machine first to copy either 5 or 20 pages. (The number of pages the experimenter had, in combination with the number of pages the subject had, determined whether the request was small or large. If the subject had more pages to copy than the experimenter, the favor was considered small, and if the subject had fewer pages to copy, the favor was taken to be large).

The three types of request were a little simpler:

1. Request only. "Excuse me, I have S (20) pages. May I use the xerox machine?"

2. Placebic information. "Excuse me, I have 5 (20) pages. May I use the xerox machine, because I have to make copies?"

3. Real information. "Excuse me, I have S (20) pages. May I use the xerox machine, because I'm in a rush?

And there was another independent variable, whose effects are not reported in detail:

Half of the experimental sessions were conducted by a female who was blind to the experimental hypotheses, and the remaining sessions were run by a male experimenter who knew the hypotheses.

We're told that "Not surprisingly, the female experimenter had a higher rate of compliance than the male experimenter, but since there were no interactions between this variable and the others', the data are combined in the table for ease of reading."

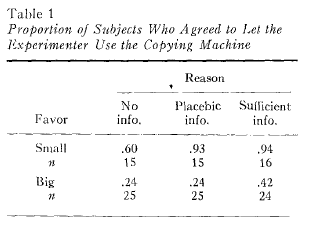

Sex aside, the table of results was:

The biggest effect by far was the size of the favor: when the experimenter had more pages to copy than the subject ("big favor"), the subject said "no" about 70% of the time; but when the experimenter had fewer pages to copy ("small favor"), the subject said "no" only about 17% of the time.

This effect obviously interacts with the type of request, affirming a central theme discussed in the paper:

[I]t was assumed that people would not behave in this pseudothinking way when responding was potentially effortful. Then, there is sufficient motivation for attention to shift from simple physical characteristics of the message to -the semantic factors, resulting in processing of current information. Thus, it was predicted that as the favor became more demanding, the placebic information group would behave more like the request-only group and differently (yielding a lower rate of compliance) from the real-information group.

In fact, this worked out almost categorically — in the "small favor" condition, the placebic-information group behaved almost exactly like the real-information group, while in the "big favor" condition, the placebic-information group behaved almost exactly like the request-only group.

But this isn't the lesson that Prof. Kahneman asks us to draw. He interprets the experiment — or perhaps remembers the experiment — as showing that

statements that had the form of an unqualified request were rejected (e.g., “Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine?”), but almost any statement that had the general form of an explanation was accepted, including “Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine because I want to make copies?”

But if we re-arrange the results according to Kahneman's description, combining the small-favor and big-favor rows, we get:

| Request only | Placebic explanation | Sufficient explanation |

| 0.375 | 0.50 | 0.628 |

Thus it's not true that "statements that had the form of an unqualified request were rejected" — in fact, they were accepted almost 40% of the time overall, and when the requested favor was small, they were accepted 60% of the time. Nor was it true that "almost any statement that had the general form of an explanation was accepted, including 'Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine because I want to make copies'" — in fact, the placebic requests were rejected 50% of the time overall, and 76% of the time when the requested favor was large.

In a seminar on experimental design and interpretation, I'd expect the students to pick up a few problems with the Langer-Blank-Chanowitz experiment taken as a whole. One issue is that the different forms of request are of different lengths, with the "request only" case being shorter. (And the "placebic" request, in this case, was so moronically self-involved that subjects may have been motivated to grant a small favor out of pity, bemusement, or reluctance to argue with an idiot.) Another issue is the status and situation of the subjects — presumably they were a mixture of students, faculty, and secretaries or other administrative workers; and the lower-status subjects might have had a different mix of job sizes, a different set of time constraints, and a different copying culture. (And of course, we ought in any case to be cautious in drawing conclusions about human nature from the behavior of New York City intellectuals in copier lines…)

But the problem with Prof. Kahneman's interpretation is not that he took the experiment at face value, ignoring possible flaws of design or interpretation. The problem is that he took a difference in the distribution of behaviors between one group of people and another, and turned it into generic statements about the behavior of people in specified circumstances, as if the behavior were uniform and invariant. The resulting generic statements make strikingly incorrect predictions even about the results of the experiment in question, much less about life in general.

This is especially ironic given the focus of Prof. Kahneman's own research on psychological mechanisms that undermine rational choice.

I should stress that I'm not opposed to summarizing and generalizing, and that I'm not trying to call Prof. Kahneman's accomplishments into question. My point is that the habit of thinking accurately about the properties of distributions is a very difficult one to establish and maintain, even in simple cases; slips are common, even among very smart and well-informed people; and the result is often something that "Everyone knows" despite the fact that it isn't true.

Unfortunately, many science journalists don't even try, and perhaps in some cases don't have the (simple) conceptual training needed to get things straight in the first place. As I've suggested before, this aspect of our culture, from a certain point of view, is as puzzling as the Pirahã's lack of interest in counting.

[N.B. The line-cutting study was one of three experiments discussed in the 1978 paper, and the subjects are described as "120 adults (68 males and 52 females) who used the copying machine at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York". Since Langer was at Harvard, while Blank and Chanowitz were at CUNY, it would probably be more accurate to attribute this experiment to them rather than to her alone; but such are the perils of authorship order.]

Spell Me Jeff said,

May 3, 2009 @ 10:47 am

To make a sweeping generalization, Mark, all this results from the death of the sliderule.

I've taught critical thinking and "research paper" writing to undergrads for, errp, 23 years. By and large, their impression of science is that it teaches absolutes, NOT probabilities. Part of the reason, I suspect, is that they are engaged with the lowest denominator of the products of science, ie that bastion of stable truth, the textbook (not realizing that even textbooks are not stable over time). Then there is the media contribution. TV and film scientists are always out to "prove" things, and when they do, naturally they find the "right answer."

So I've seen this kind of thinking up-close and ugly in what must be thousands of student papers by now. A few students get it (don't ask how many) but many more don't.

I bought my first scientific calculator in the late 1970s. I was a kid, and they were just getting affordable. My chem teacher would not let us use them. He insisted we use sliderules, which were already getting scarce. One reason was to keep us engaged in the math. Another, I think, was to keep us conscious that the solution to our problems always lay in that blank space between the marks on the ruler — that there would always be a margin of error. It's a mindset that needs to be cultivated, even among scientists, apparently.

mgh said,

May 3, 2009 @ 12:18 pm

I understand your point but, in the context of a review, making passing reference to a 25-year-old experiment, I wonder if you really think that level of detail is appropriate? Aren't there cases where both writer and audience consent to a trade-off between completeness and comprehensibility (something like "as simple as possible but no simpler")?

The author omitted experimental details (as one does in a review) to emphasize the more striking conclusions, referring only to the "small favor" data and not mentioning that the placebic effect diminishes for big favors. But, reading his review, I wouldn't have concluded that subjects were, for example, more likely to conspire in murder when offered a placebic excuse ("Pardon me, would you take this gun and shoot that man because I need him to be killed.") Although, surely, if the experimenters had run this experiment, and lumped it with the other conditions as you did, the placebic effect would have been even smaller.

My basic point is that this writer and his audience have a different tacit understanding about "generalization and truth" than do, for example, an educational consultant and a roomful of grade-school teachers.

Dan Lufkin said,

May 3, 2009 @ 12:40 pm

I think that the demise of the slide rule was even more dire than SMJeff posits. Never mind the space between the marks; when you used a slide rule you had to do the orders of magnitude in your head. You had to know whether the answer was 3.14 or 31,400. Do this enough and you develop a sense of how magnitudes fit together and an intuitive appreciation for what "significant figures" mean — an answer can never be more accurate than the least accurate factor.

Physicists used to amuse themselves by asking "Fermi questions" (q.G.) like How many piano tuners are there in Chicago?. If you had teethed on a slide rule, you knew how to approach the problem. A calculator is of little help.

mgh said,

May 3, 2009 @ 1:02 pm

that reminds me of what the quipu user said about the abacus…

Mark F. said,

May 3, 2009 @ 1:09 pm

I don't think slide rules have much to do with it. Kahneman is old enough to have learned to use one, and yet he was the one doing the oversimplifying in this case.

Categorical thinking can be seen as a form of rounding; roughly speaking you're rounding p values the nearest integer. And rounding is an inherent simplification — there are just fewer bits to remember. So it's no wonder that people do it.

What I did May 3rd - Eddie Current said,

May 3, 2009 @ 3:33 pm

[…] Generalization and truth — 5:40am via Google Reader Good […]

A Reader said,

May 3, 2009 @ 7:35 pm

@mgh- it's not a matter of simplification, though. If it were, I doubt Mark would have written this. The problem is that the reviewer didn't present 'the more striking conclusions', which have to do with how difficult a request has to be before 'critical thinking' is applied. The reviewer instead talked about something else that really didn't follow out of the study.

mgh said,

May 3, 2009 @ 7:56 pm

A Reader, isn't an effect more interesting than lack of an effect? In any case, if you read the passage in context, the discussion is about circumstances where self-monitoring of cognition is lax, so only the "small favor" data seems relevant.

A Reader said,

May 3, 2009 @ 9:22 pm

@mgh, I did read the immediate context, and I don't see how it justifies anything- given the topic being discussed, the reviewer really ought to have discussed the differing results under different circumstances. Instead, the article is simply used to talk about 'a well-known example of what she called “mindless behavior', rather than presenting the article more accurate _and_ tying it more to the topic of that section.

At least that's what I get out of the part of Kahneman's article that I read and Mark's summary of Langer et al's piece.

Michael Alan Miller » Why I always yammer about complexity said,

May 4, 2009 @ 11:08 am

[…] article deals with the same […]

Mihai Pomarlan said,

May 5, 2009 @ 2:21 pm

So … does this mean we should all learn Lojban now? Or maybe even that is inadequate (it's merely supposed to be a Logical Language, after all), so we need to construct a Proban or something similar.

Yes it would be inconvenient and not transparent, but imagine if all science papers were written in Proban, and you'd have authorized translators writing up the press releases, they'd be incentivized to think about some way to properly express the information.

****

Ok, I am not entirely serious. But, if our poor intuition of probability were language-related*, what could we do to amend it?

*: then again, according to

this test on philosophers.net (based on work by Peter Wason, Leda Cosmides & John Tooby)

us human beings have a poor grasp of logic when dealing even with simple abstract settings, which nonetheless vanishes when deciding whether some (for some value of) simple social rule was broken or not.

So maybe we are just not wired to be rational gamblers either.

Transor Z said,

July 8, 2009 @ 11:45 pm

Thanks for this and the helpful leads it provides. I just encountered the term "placebic information" in the context of financial media coverage of current economic events. Very interesting concept.

Queen of Diamonds: the Manchurian Candidate in all of us « Pick your poison said,

August 10, 2009 @ 10:21 pm

[…] Sources: Mark Liberman's blog on Language Log out of UPenn: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1396 […]