Wrecking a nice beach

« previous post | next post »

Under the subject line "Things you never thought you'd get to say", Bob Ladd sent me this note yesterday:

You are among the few people I know who will appreciate this anecdote:

It's been unusually cool, wet, and windy in many parts of the Mediterranean this summer, including our part of Sardinia. On our last full day there last week, our local beach was still unpleasantly rough and windy, so we decided to go to a place called La Licciola about 10 miles away, on the other side of the headland and therefore protected from the wind. The last time we went there a couple of years ago, the final access was a long downhill stretch of dirt road with what amounted to a field to park in at the bottom. It was fairly chaotic in a typically Italian way, with people managing to park along the edges of the dirt road when the field got full, but with everyone always leaving just enough room to get through. Anyway, the other day we got to the top of the downhill road to discover that it has been properly paved, with an actual sidewalk along one side and no-parking signs on the other (though everyone was parking there anyway). The parking field has been improved with clearly delineated spaces and there was a chain across the entrance because it was already full. People were having a hard time turning around because the sidewalk has narrowed the driveable part of the downhill road, and new people kept coming in at the top of the hill looking for a space to park, creating more chaos. We decided to give up and go somewhere else, but it took us the better part of 15 minutes to extract ourselves from the mess. It was only on the way back out to the main road that it occurred to me that, in trying to improve things, they had managed to, well, wreck a nice beach.

It was my misfortune to be sharing the car with someone who wouldn't have understood why I was giggling.

In the interests of increasing technological literacy, I'll fill our readers in on the background of Bob's chortles. Much of this history is unknown even to (most of) those in the speech technology field who are quite familiar with the clichéed homophony "recognize speech"≅ "wreck a nice beach".

The story starts with a passage from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's autobiographical novel In The First Circle, which was first published in an abridged English translation in 1968 (though the quote below is from a more recent translation of the original version by Fred Willets, 2009). Tiny but relevant glimpses of this book can be found in "The world in a grain of sand", 9/29/2008, and "Speech-based lie detection in Russia", 6/8/2011 — but if you haven't read (In) The First Circle, you should definitely put it on your reading list!

The context is the Marfino sharashka in the early 1950s. Sharashkas were a uniquely Soviet combination of research laboratory and prison, where political prisoners were made to work on projects of interest to the authorities.

JUST AS ORDINARY SOLDIERS KNOW, without being shown the battle orders from headquarters, whether they are part of the main offensive or a supporting action, so the three hundred zeks in the Marfino sharashka had correctly deduced that Number Seven was the decisive sector.

No one was supposed to know Number Seven’s real name, but everybody in the institute did. It was the “Clipped Speech Laboratory.” “Clipped” was an English word. Not only the engineers and translators in the institute but the fitters, the turners, the grinders, perhaps even the deaf and slow-witted carpenter, knew that the original models for the installation were American, though officially they were “ours.” This was why American journals with diagrams and theoretical articles about clipping, which were on sale on newsstands in New York, were here given serial numbers, stapled, classified, and, to frustrate American spies, sealed up in fireproof safes.

Clipping, damping, amplitude compression, electronic differentiation, and integration of random speech—it produced an engineer’s parody of human speech. It was as if someone had taken it into his head to dismantle New Athos or Gurzuf, put the material in little cubes in matchboxes, mix them all up, fly the lot to Nerchinsk, sort them out, and reassemble them precisely as they were before, reproducing the subtropics, the sound of the surf, the southern air, and moonlight.

This was just what had to be done with the speech reduced to little packages of electrical impulses, and what is more, it had to be reproduced not only so that it could be understood but so that the Boss could recognize the voice at the other end.

(New Athos and Gurzuf are Black Sea resort towns.)

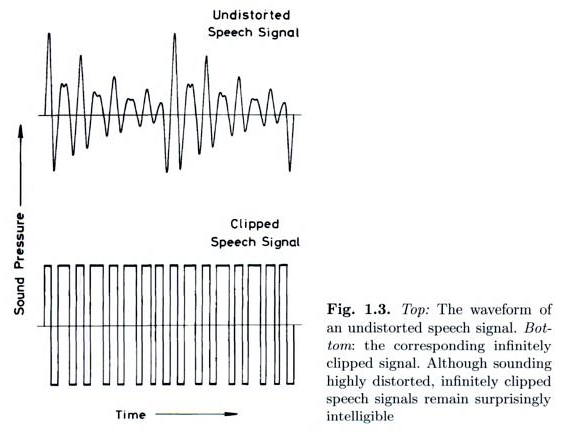

In this context, I believe that "Clipped Speech Laboratory" might better be translated for modern readers as "Digital Speech Laboratory", for reasons that are suggested by this figure from Manfred Schroeder's 2004 book Computer Speech: Recognition, Compression, Synthesis:

Some vocoders of the First Circle era used a filter bank to decompose the input into a set of bandpass signals, each of which could be turned by "infinite peak clipping" into a digital signal, preserving only two (positive vs. negative) of the original signal values. The resulting digital filter bank outputs — each a binary stream — can then in principle be reconstituted and recombined with relatively good fidelity, thanks to underlying mathematics proved as a theorem in 1977 by Ben "Tex" Logan. "Electronic differentiation and integration" comes into play because differentiation (= high frequency emphasis), infinite peak clipping, and integration (= low frequency emphasis) can produce a better result than infinite peak clipping alone. And I suspect that the stuff about "little cubes in matchboxes" probably refers to encryption techniques permuting the order of the frequency bands in different time frames.

The next step in the beach-wrecking saga involves my former colleague Manfred Schroeder. I'll let Dave Tompkins tell the story, in a passage from his 2010 book How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Vocoder from World War II to Hip-Hop, The Machine Speaks:

During the Big Bug Fifties, when movies depicted Communists as giant ants, the Kremlin denounced any Soviet praise of American teknik. By then the United States had fallen suspect to another paranoid Joe, this one a senator from Wisconsin. One of Senator McCarthy’s more ardent subscribers was Homer Dudley, inventor of the vocoder. Dudley’s protégé, Manfred Schroeder, learned this when he was hired by Bell Labs after immigrating to New York from Germany in 1954. “There were two things Homer Dudley liked to talk about,” says Schroeder. “The Communists and the vocoder. I didn’t have the words at my fingertips in those days, but today I would call him a right-wing nut. He thought the State Department was infested by Communists.”

Manfred Schroeder served on a German artillery target acquisition unit during the war, identifying blips in the fog. At times, Russian POWs manned the guns in exchange for food. “They were Communists; they were nice people,” he says. “When Sputnik went up in 1958, Dudley came to my desk with the following idea. He said the Russians could not put up a satellite like that and the beep-beep-beep that people heard around the world, coming from Sputnik, was just an electronic fakery.”

Working with Dudley in the acoustics department, Schroeder would consult The First Circle while developing his own voice-excited vocoder— the first of these machines to actually sound human. Demonstrating for his associates, Schroeder assumed that his vocoder could be understood, only because he’d been listening to it all day, the same pratfall that occurs in The First Circle. Struggling between intelligibility and just hearing things, he noted its annoying habit of turning a phrase. “How to recognize speech” sounded like “How to wreck a nice beach.”

“People will go to any length (and width) to be unintelligible,” wrote Schroeder in his book Computer Speech: Recognition, Compression, and Synthesis. So much for the Language of Maximum Clarity.

In The First Circle, Solzhenitsyn compared speech encoding to disassembling a beach and then re-synthesizing it at another location— essentially transposing a summer getaway as if it were a Soviet munitions factory on the run. He called it “an engineering desecration,” the equivalent of pulverizing a southern resort into grits, sticking them into a billion matchboxes, shaking them up and then flying them to a different sector for reconstruction. “A re-creation of the subtropics, the sound of the waves on the shore, the southern air and moonlight.”

The sand in your shorts, the bad radio reception, the copper tonality, the jellyfish parachute squishing between your toes, the effervescent fizz of unvoiced surf. The burning red sun. For the zeks at Marfino the vocoder could make getaways out of sentences, if only inside their heads. A gulag prison term, an imagined escape. The last re-sort, a desperate scramble. As if Solzhenitsyn had burst from his lab table in a flock of schemata, his beard tangled with headphones, denouncing the artificial beach. Somebody had to say something.

In passing, I should note that the "pratfall" — synthetic speech that sounds fine to its creator but is unintelligible to others — is generally not caused by "listening to it all day", but rather by knowing in advance what it's supposed to be saying, which brings to bear the top-down perceptual effects that in extremis produce the Phoneme Restoration Effect. My personal favorite example of this phenomenon is described in "The dogs of speech technology", 3/1/2005.

I can vouch for Dave Tompkins' suggestion that Manfred saw The First Circle as a text with strong personal as well as technical resonances, and his "recognize speech" → "wreck a nice beach" example is without doubt one of the echoes.

By 1980 if not earlier, Manfred's phrase had become part of the culture of speech technology, used in dozens if not hundreds of presentations and papers. Thus J.S. Bridle et al., "Continuous connected word recognition using whole word templates", Radio and Electronic Engineer, 1983:

Furthermore, there can be very small acoustic differences between some word sequences, so that even humans have to rely on the context to deduce the identity of the words (eg 'recognize speech' and 'wreck a nice beach').

Or J. Picone et al., "Automatic text alignment for speech system evaluation", IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 1986:

The basic problem associated with text alignment is the definition of a meaningful distance metric between two text units, such as words or phonemes, such that the degree of similarity between the two strings can be maximized. Any similarity measure used in an automated scoring algorithm must be a perceptually based measure. It is important that the output of the algorithm accurately interpret the listeners’ impressions of the stimulus data. For instance, two homophones differ in spelling, yet are identical phonemically (for example, “scent” and “cent”). Puns play on the similarity of sounds in words while having radically different spellings and meanings (“to wreck a nice beach” and “to recognize speech”). It is not clear how text strings can be aligned using only the raw text. Our approach is to accommodate these problems by performing matching at the phoneme level. Phoneme-to-phoneme distances can then be computed in a perceptually meaningful way based on experimentally derived phoneme-to-phoneme distances which have been collected through various listening experiments.

Of course, the idea of "homophonic translation" is much older — an important reference is Howard L. Chace, Anguish Languish, 1956. But the "wreck a nice beach" example came into the field because Solzhenitsyn's metaphor inspired Schroeder's fragment of poetic homophony.

Ben Zimmer said,

August 5, 2014 @ 12:35 pm

The earliest hit for "wreck a nice beach" on Google Books appears to be:

(Pieced together from snippet view.)

[(myl) That makes sense. I dimly recall having heard the "wreck a nice beach" example during the DARPA SUR project 1972-1975, though I wasn't directly involved in it. And "Anguish Languish" was a popular reference during that time. But I couldn't find a specific reference for the "wreck" trope from that period.

I'm fairly certain that that Manfred Schroeder was the original "wreck a nice beach" source, though, unless there was some other Solzhenitsyn junkie in the speech technology field between 1968 and 1973. Manfred certainly connected it with The First Circle when I first heard it some him in 1975 or 1976.]

Q. Pheevr said,

August 5, 2014 @ 2:54 pm

To wreck a nice beach, you need only burn shit faster.

MaryKaye said,

August 5, 2014 @ 7:18 pm

I think there is probably some input from familiarity with the device as well as foreknowledge of what it is saying: at least, this is true with difficult-to-understand humans, as I learned from my speech-impaired younger sibling and my Korean-speaking labmate. Both of them went through a phase where the family/lab could understand them but no one else could. At least with the grad student it wasn't all foreknowledge, as he worked in a field of math I wasn't particularly good with, and we also chatted about Korean culture once or twice.

The earliest talking video game I encountered, _Wizard of Wor_, was also notorious for people only realizing what it was saying after substantial exposure. (IIRC, it was saying "My babies are radioactive" and "I'll pop you in the oven.")

Pflaumbaum said,

August 5, 2014 @ 8:12 pm

Something I've been wondering about… in words like speech, I gather that the voicing of the second segment is generally regarded as neutralised. But is there any consensus on whether this is an underlying /p/ or /b/, or an 'archiphoneme', or something else?

Phonetically, the unaspirated sound in speech is presumably closer to [b] than to (initial) [p] irrespective of voicing (since, as I understand it, aspiration is if anything more contrastive than voicing for English plosives). At any rate, to me wreck a nice peach, at least articulated in isolation, works less well as a pun – the aspiration militates against hearing it as speech.

Does language acquisition provide any evidence? The reason I've been wondering about this is because listening to my 2-year-old daughter, who until recently couldn't form clusters with natal /s/, I heard /puːn/ and /paidə/ for 'spoon' and 'spider', with aspirated /p/ – which made me think she was categorising these phonemes as /p/.

Similarly she had /top/ for 'stop' and /kin/ for 'skin'. On the other hand, I did note down /gɔːd/ for 'scored' and /grɛip/ (realised as something like [gwʌjp]) for 'scrape'.

But I appreciate that how I analysed the sounds may not correspond to what she actually produced.

Pflaumbaum said,

August 5, 2014 @ 8:14 pm

*with initial /s/*, that should be.

Ray Dillinger said,

August 5, 2014 @ 8:57 pm

Bearing in mind that my end of computational linguistics was more about gathering threads of semantic meaning among written words, there are other phrases equally infamous.

I had a similar experience on meeting an employee of one of our clients – a Frenchwoman who was at that moment accompanied by a beagle – to whom I had to apologize profusely for unexplained chuckling.

Jon said,

August 6, 2014 @ 3:28 am

The problem of recognising word boundaries in continuous speech is shared by scientists from many countries who have to attend conferences where all presentations are in English. When I used to attend such meetings, I used to try to make my talks intelligible to all. The trick is to make each word distinct and separate without sounding robotic. The trick is obviously well understood in the teaching community. A Hungarian who had asked me "Why is it I can't understand the BBC World Service, but I can understand you?", played me an English language learning tape that he had, someone reading a narrative. I could hear the speaker using the same method I used.

AntC said,

August 6, 2014 @ 5:42 am

Thank you Mark, fascinating article.

The homophone doesn't work for me (BrE), so I took a little while to cotton on to why Bob was chortling.

recognise's middle syllable is as in cognate with a back vowel and hard 'g'.

Pflaumbaum said,

August 6, 2014 @ 7:11 am

@AntC

Really? I'm BrE too, and I would say ['rɛkənaiz] in fast connected speech and ['rɛkəgnaiz] in slower/more formal speech. Those are also the possibilities given in the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary.

You seem to be saying ['rɛkɔgnaiz], with /ɔ/ in an unstressed syllable, which to me sounds bizarre. I'd be surprised if I'd ever heard it unless someone was trying to explain how the word was spelt.

Terry Hunt said,

August 6, 2014 @ 7:37 am

@AntC – Also BrE, and FWIW I worked out the homophone above the cut (despite no familiarity with Linguistics Academia besides being a regular reader here), before clicking 'read more' to find the confirmation. I wonder if it's a regional thing, or a cultural one? (Being an SF/F fan, I'm well-used to horrible puns.)

However . . .

@Ray Dillinger – I confess inability to parse your example (something involving 'beagle'?) Please unpack.

Terry Hunt

D.O. said,

August 6, 2014 @ 12:20 pm

There is an interesting problem for translator in Solzhenitzyns quote. “Clipped” was an English word actually was a longer sentence in Russian

The second half explains what clipped means in Russian. Something like "The word clipped was from English and meant "cut down" speech." Clearly the translator didn't see a need to explain to English speakers what clipped means, which is kind of reasonable, but also kind of not. After all it is a Russian novel and he already decided to include an obvious statement that clipped was an English word.

AntC said,

August 6, 2014 @ 3:57 pm

@Pflaumbaum, I guess it's always dodgy self-monitoring. In fast speech, my vowel might become neutral, but there's definitely still a /g/.

@TerryH my regional thing is mostly RP-ish (brought up in an outer West London suburb), but with traces of East Anglian, Yorkshire, and NZ rising intonation.

Ray Dillinger said,

August 6, 2014 @ 4:49 pm

One of the semi-classical examples to show beginning students the difficulty of parsing the crazily ambiguous grammar of natural languages is to list all the possible meanings of a relatively simple English sentence. And the example used in at least one major text was:

"I knew a lady with a dog from France."

First, is it the lady, the dog, the condition of knowing, or some combination of these, that originated in France? (It could be an Italian woman with a German dog whom the speaker met in Paris.)

Second, when the word "lady" is used, is it in the aristocratic sense (possibly implying that the lady in question was British, or that the sentence was written in pre-revolutionary times), or the general female-adult sense?

Third, when the word "knew" is used, what does the past tense imply has ended? Knowledge, the lady, the dog, some combination of these things, or just the association of any of the above with France?

Fourth (and usually only brought up if judgement allows that no one will be offended by it) is the verb "knew" intended in the sense of mere knowledge, or in the so-called 'biblical' sense as a euphemism for a much more complete kind of knowledge?

Anyway, if you enumerate the possible combinations, it quickly becomes apparent that even the simplest of sentences does not contain within itself nearly enough information to disambiguate it. Which quickly leads to the need for statistical methods of word sense disambiguation, sentence structure disambiguation, statistics-guided parsing, etc.

Mark W. said,

August 11, 2014 @ 4:11 pm

Pflaumbaum: Does language acquisition provide any evidence [about the realization of voiceless stops after /s/]?

Well, here's my own experience: I have a high-frequency hearing loss, so it's harder for me to hear higher-frequency phonemes like /s/. Until I had speech therapy in my teenage years, I couldn't produce those clusters (and many others), and I didn't start consistently producing them until I was 18.

Before my speech therapy, I consistently pronounced them as voiceless unaspirated stops; hence "spy", "pie", and "buy" for me were /pai/, /pʰai/, and /bai/.

marie-lucie said,

August 11, 2014 @ 8:18 pm

The lady from France's beagle: perhaps the way she said "beagle" sounded to the listener like "pickle".

fiona hanington said,

August 12, 2014 @ 2:08 pm

I've not heard of this homophony before, nor am I a linguist…. So when I saw the title of this piece I thought there was *just* a chance it would be about Vancouver's clothing-optional Wreck Beach. A place that I have yet to visit despite having lived in Vancouver for a number of years now.

Killer said,

August 15, 2014 @ 9:29 pm

I was reminded of this post today when I heard one of those "Support for this podcast comes from" announcements before a Fresh Air interview. I thought the (human) woman said "Zipper Cruder dot com"; eventually I figured out that it was "Zip Recruiter."