Writ in water

« previous post | next post »

In a Beijing park last week:

According to this story,

Chinese water calligraphy is often seen as the quintessential old man's hobby. Every morning, elderly men gather in Beijing's parks to practice this ancient art on the ground with giant brushes dipped in water, writing fluid lines of ancient characters that disappear one by one as they dry.

And indeed, the calligrapher that I saw was an elderly man:

Another article suggests that this version of the "ancient art" was developed only about 25 years ago:

In China cosmogony, the square or ‹di› represents the earth and the circle represents the sky; ‹shu› signifies book, writing by association. The expression ‹dishu› literally means square calligraphy, i.e. earth calligraphy: practicing ephemeral calligraphy on the ground, using clear water as ink.

Very popular nowadays, this recent phenomenon appeared in the beginning of the 1990s in a park in the north of Beijing before spreading in most of major Chinese cities. Thousands of anonymous street calligraphers operate daily in parks and streets, the different pavements becoming a large paper surface. Displaying literature, poetry or aphorisms, these monumental letterings, ranging from static regular to highly cursive styles, convoke the whole body in a spontaneous dance and infinite formal renewals. The calligraphic practice corresponds to a research of self accomplishment or improvement, this improvement modifying our perception of the world.

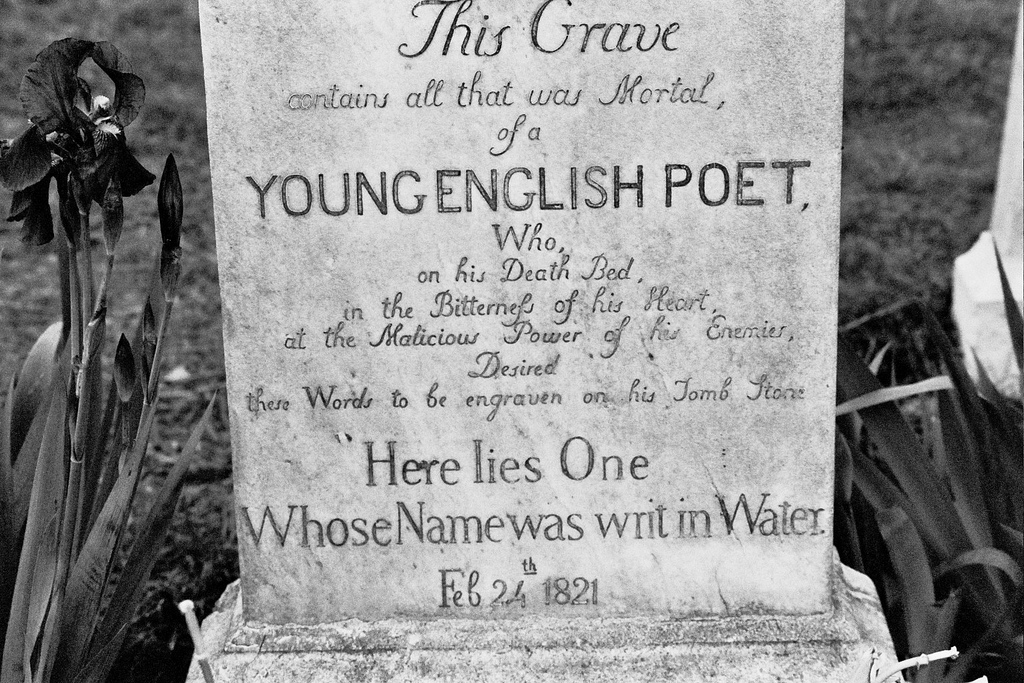

On this account, 地書 dìshū — writing on the ground with water — is rather like the other performances on display in Chinese parks, with different cultural resonances from the traditionally-imagined impermanence of the "writ in water" phrase on Keats' gravestone:

which presumably echoes the earlier history of the metaphor, as in Donne's Expostulation

Are vowes so cheape with women, or the matter

Whereof they are made, that they are writ in water

or John Taylor's 1625 Funerall Elegie vpon King James

His anger written on weake water was,

His Patience and his Loue were grau'd in Brasse.

and back to Catullus 70 and beyond

Nulli se dicit mulier mea nubere malle

quam mihi, non si se Iuppiter ipse petat.

dicit: sed mulier cupido quod dicit amanti,

in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua.

But I don't know anything about Chinese literature or Chinese cultural history — maybe water calligraphy has some other and older associations?

Rebecca said,

July 4, 2014 @ 11:05 pm

I once was given a calligraphy set which included a board covered in some special paper and some water color brushes. The idea was to do Chinese calligraphy "in the moment" for meditative purposes, but the pamphlet that came with it implied that such set-ups were traditionally used to learn/practice calligraphy in an economical way that didn't waste paper and ink on poor execution. I took that to be marketing hype, but perhaps it had some basis in truth.

leoboiko said,

July 5, 2014 @ 4:59 am

My Taiwanese teacher did get some durable paper that darkens when wet, and I was told to reserve some brushes (i.e. to keep then away from ink) to practice with water, for purely economical reasons ("this lasts forever!"). Such water-paper is relatively common and may be found in specialist stores, often pre-printed with models from famous calligraphers of the past.

I don't think they're related to the water calligraphy hobby described in the post; at least, when I got mine, no one told anything about the poetics of impermanence or the like. Rather, I was told about how some ancient master or another couldn't afford materials, so he'd practice writing in mud on his walls. So if there was any sort of moral, it was "keep practising even if you're broke".

Jongseong Park said,

July 5, 2014 @ 6:24 am

Sixteenth-century Korean calligrapher Han Ho 한호(韓濩), known better as Han Seokbong from his pen name Seokbong 석봉(石峯), was said to have practiced calligraphy with water on stone or pottery surfaces because his family was too poor to afford ink and paper. He can't have been the only one to practice calligraphy with water as ink.

Victor Mair said,

July 5, 2014 @ 8:38 am

My impression, from watching such elderly gentlemen writing with water on the ground in the parks next to people doing taiji (Tai-Chi), qigong (Chi-kung), Falun Gong (before the crackdown in 1999), etc., and dancing is that for them it is also a sort of gentle exercise (big brush, dipping in the water, swooping movements) — a sort of kinetic-cum-esthetic practice with philosophical overtones (the evanescence of things).

I've been going to China regularly since 1981, but don't remember seeing this before about twenty years ago.

Jerry Friedman said,

July 5, 2014 @ 10:17 am

The story MYL linked to is about an art project that seems remarkable to me.

"Nicholas Hanna, a Canadian media artist living in the Chinese capital, has invented a tricycle that writes Chinese characters with water."

John Maline said,

July 5, 2014 @ 2:33 pm

Just visited China for first time and saw a man doing water calligraphy in the Temple of Heaven park. Quite beautiful. It was probably June 26. I don't see myself in the background but it sure looks like a similar setup. Small world.

Neil Dolinger said,

July 5, 2014 @ 3:29 pm

The few times I have seen water calligraphy, it has been performed by Buddhist monks in their temples, so I had assumed its origins were in Buddhism.

GP said,

July 5, 2014 @ 4:33 pm

Image from a park in Shanghai last year. This calligrapher began practicing when he retired over 20 years ago.

GP said,

July 5, 2014 @ 4:33 pm

The link to the image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gpparker/9201651345/

Matt said,

July 6, 2014 @ 8:00 pm

I don't know about writing with water, but writing in water has been a thing in Chinese at least since the Buddhist Canon started to be translated into that language, like this example from the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra:

(I don't know what, if anything, this corresponds to in Sanskrit.)

Nishizawa Kazumitsu believes that this Buddhist image is the ultimate source of the first half of one of Hitomaru's poems: