Another thing coming about another think coming

« previous post | next post »

Last week, I discussed some of the things that Rev. Jeremiah Wright had to say at the National Press Club about race, language, and the brain ("Wright on language and linguistics", 4/29/2008). But I didn't discuss the passage that many journalists identified as the rhetorical and emotional core of his outburst. (Click the link to hear the audio.)

This is the transcript:

In our community, we have something called playing the dozens.

If you think I'm going to let you talk about my momma,

and her religious tradition, and my daddy, and his religious tradition, and my grandpa,

you got another think coming.

Or is it?

Some newspapers transcribed those last few words the way I did, for example the Boston Globe:

"If you think I'm going to let you talk about my mama," Wright said, "then you've got another think coming."

But many others rendered it a little differently:

“If you think I’m going to let you talk about my mama, and her religious tradition,” he said, pausing a beat, “you got another thing coming.” (New York Times, 4/28/2008)

He added: "If you think I'm going to let you talk about my mama and her religious tradition . . . you got another thing coming." (Washington Post, 4/29/2008)

If you thought that once the Rev. Jeremiah Wright traded his pulpit for a podium he'd be less of a threat to Barack Obama's presidential aspirations, in the words of Wright, "you got another thing coming." (Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 4/30/2008)

Let's leave aside "you've got" vs. "you got", and focus on "another think coming" vs. "another thing coming". The testimony of transcribers is clearly equivocal. As for my own impressions, I first heard "think", but I can hear it as "thing" if I try.

The difference doesn't have any political implications, but several readers asked about it, and it brings up some interesting linguistic issues. So I spent some time this morning writing an explanation of why this word sequence is likely to be ambiguous.

I don't need to say anything here about the history of the eggcorn "another thing coming" for "another think coming", since we've already covered that question at length. (For details, see "Another thing coming", 9/28/2007; "Have another think", 9/28/2008; and also "The thin line between error and mere variation (Part 1 of 2)", 6/29/2004.) The original expression is "another think coming", but "another thing coming" has been competing with it since 1919 at least, and is winning the battle of Google hits these days. So if Rev. Wright made that choice, he's in good company.

The fact that this came up in a recorded question-and-answer session draws our attention to an central feature of this kind of variation: the spelling is different but the sound is similar or identical. As a result, it's often impossible to decide which alternative a speaker chose on some particular occasion. And of course, that's why the variation arises in the first place.

When you write (either version of) this phrase in conventional English orthography, you have to choose between writing "think" and writing "thing". These are very different words. They mean different things, they mostly occur in different contexts, and in many contexts they sound quite different. In isolation, the standard pronunciations, rendered in the International Phonetic Alphabet, look like this:

"think" [θɪŋk]

"thing" [θɪŋ]

[θ] represents the voiceless dental fricative at the start of "thistle" or "thought", or the end of "moth" or "wrath".

[ɪ] represents the vowel in "hit" or "miss".

[ŋ] represents the velar nasal at the end of "ding" or "dong".

And [k], of courses, is the voiceless velar stop at the start of "kiss" or the end of "sick".

Except that /k/ is not so simple.

Well, when you look at the details, nothing about pronunciation is simple, alas. But in this case, the tricky part is the way that English speakers usually pronounce /k/ when it's at the end of a syllable, followed by another stop consonant at the beginning of the next syllable.

Let's take a canonical /k/ case first. Between vowels, at the start of a stressed syllable, English /k/ is a voiceless aspirated velar stop.

The "stop" part means that there's a complete closure of the airway. The "velar" part means that the airway is closed by the pressing the body of the tongue against the soft palate, otherwise known as the velum. The "voiceless" part means that the vocal cords don't vibrate during the closure, and the "aspirated" part means that they don't start vibrating again for 60 milliseconds or so after the release of the closure. (The span of time just after the release is filled with noise, created partly by turbulent flow of air through the narrow passage as the tongue body moves away from the palate, and partly by turbulent flow through the glottis as the vocal cords come together to (re-)establish voicing.)

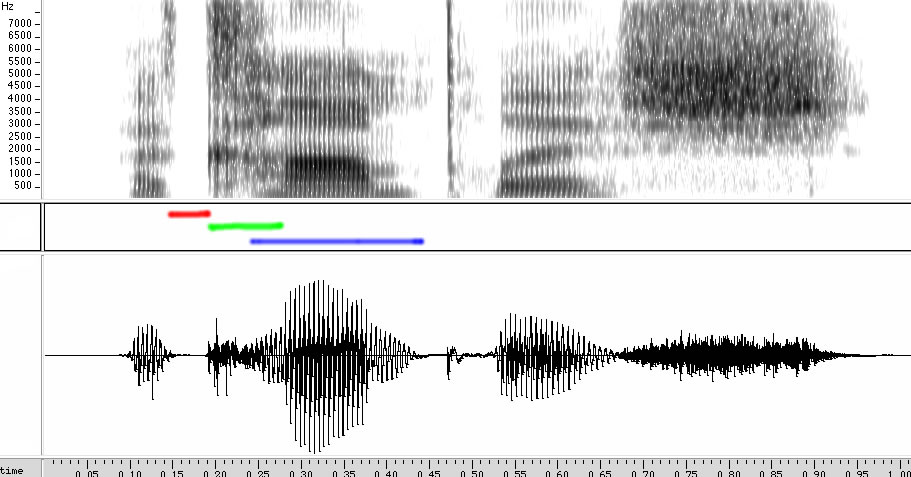

As an illustration, here's an acoustic picture of Amanda Seidl saying the word accomplish, taken from the American English Spoken Lexicon, LDC99L23. (Time goes from left to right; the bottom panel is a waveform display, in which the vertical axis indicates sound pressure level; the top panel is a spectrogram, in which the vertical axis indicates frequency, and the blackness of the plot at a given location indicates the energy of the signal at the corresponding frequency and time.

The colored lines in the middle panel show the voiceless closure of the [k] (in red), the noisy release and aspiration of the [k] (in green), and the voiced region of the stressed second syllable of accomplish, which overlaps with the aspiration in this case.

(You can click on the display for a larger version.)

Now let's look at /k/ in a different kind of context. I've taken this from the start of yesterday's Radio Times on WHYY, in which Marty Moss-Coane interviewed Gary Marcus about his new book, Kluge. She introduces him like this (again, click the link to play the sound):

My guest, psychologist Gary Marcus, uses the word "kluge" to describe memory, language, and the human mind. And this is the way he uses the word: "a clumsy or inelegant yet surprisingly effective solution to a problem".

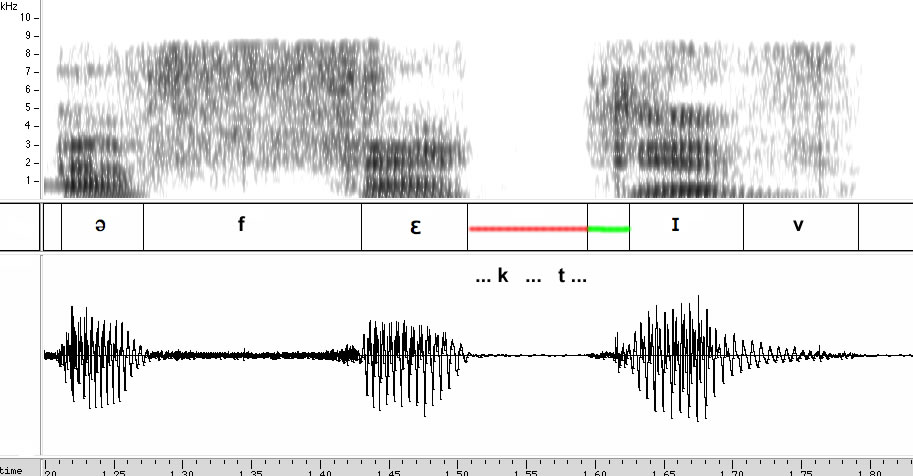

Marty Moss-Coane is a skillful and practiced professional speaker, and as you can hear if you click the link, she's enunciating especially carefully in this introductory passage, because she wants to be sure that her audience won't miss any details. Nevertheless, if we look at an acoustic picture of her pronunciation of the word effective, this is what we see:

In the middle of effective, there's a /kt/ cluster. And between vowels, at the start of a stressed syllable, /t/ would be a voiceless aspirated stop just like /k/ is. But here, we don't see two closures and two release-and-aspiration segments, one for /k/ and one for /t/ — instead, there's just one closure (marked by the red line) and just one release and aspiration (marked by the green line).

Ok, this means that the /k/ is unreleased. So how do we know that it's there?

Well, this is a curious thing. If we listen to the whole word, we hear a nice clear [kt] cluster. (Well, I do, at least.) But if we listen only to the middle syllable — even including the entire following silence — we don't hear the [k] at all. Instead, we just hear something that you might transcribe in pseudo-phonetic English as "feh", or in IPA as [fɛ].

That's because Marty has used her glottis to stop the voicing — and therefore all the sound — before she makes the [k] closure. What she says for this syllable really *is* "feh".

And when we listen just to the last syllable — again including the whole preceding silence — we don't hear [ktɪv]. In fact, we don't really even hear [tɪv]! Most English native speakers will hear this syllable, played in isolation as [dɪv]. That's because the last syllable of effective is unstressed, and so the aspiration is too short for a proper [t] in an isolated (and therefore stressed) syllable.

So how does "uh" + "feh" + "div" add up to effective?

For the whole story, you need to take a phonetics course. But a crucial piece of the story, here, is that the 85 milliseconds of silent closure between the second and the third syllable is too long to explain any other way.

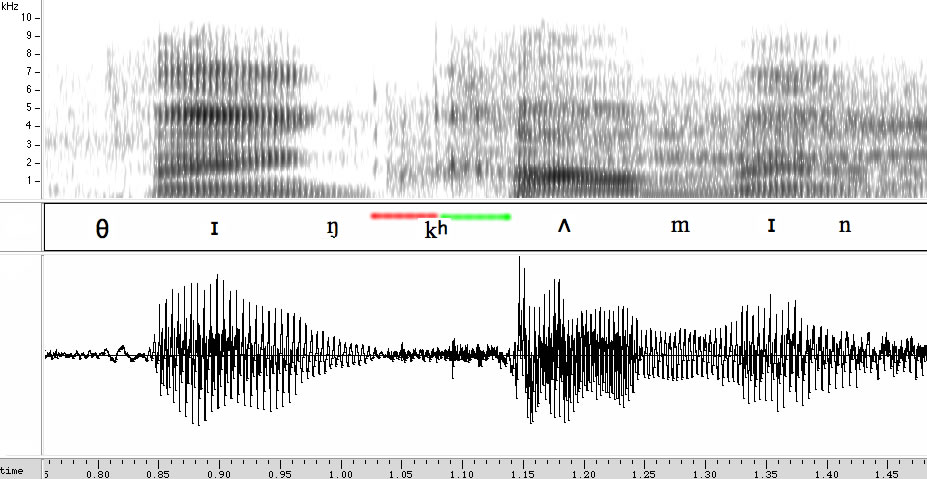

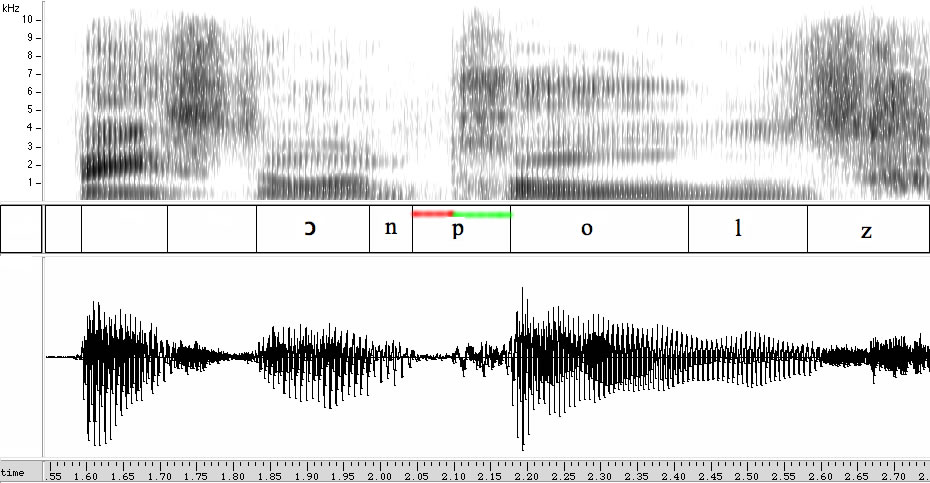

OK, now back to Rev. Wright. Listen to the audio of the critical phrase, "… you've got another ??? coming", and look at an acoustic picture of the "think/thing coming" sequence:

In between the nasal murmur [ŋ] at the end of thing-or-think, and the vowel [ʌ] of the first syllable of coming, there's a stop closure of about 55 milliseconds (marked in red) and about 60 milliseconds of aspiration (marked in green). (There's some noise during what I've marked as the "closure", but that is probably the start of the audience reaction, though it's possible that the /k/ closure has weakened to the point that it becomes fricative-like.)

That's just one closure and just one aspiration, not two — so does that mean that there's only one /k/, and therefore that Rev. Wright said "thing coming", not "think coming"?

Well, no. No native speaker of English would release the final /k/ of think in a fluent pronunciation of "think coming", any more than they would in the second syllable of "effective".

So does the duration of this stop closure tell us whether Rev. Wright meant to say one /k/ or two?

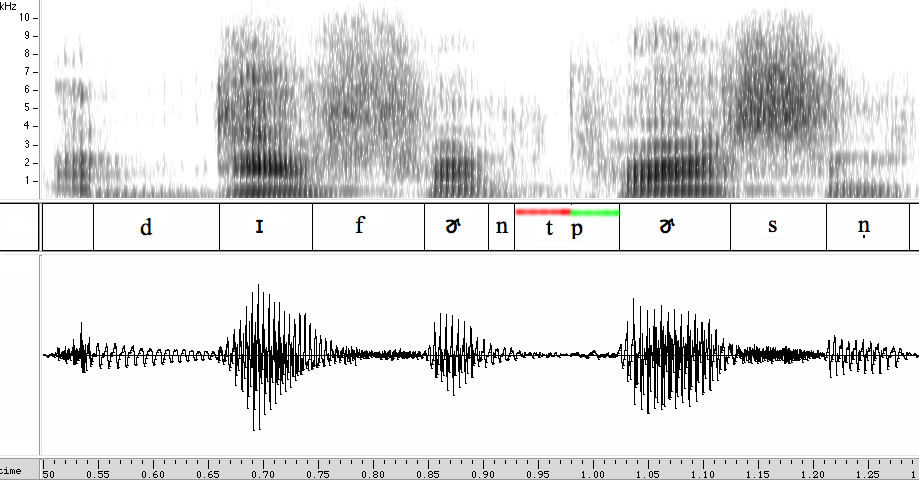

No, I don't think so. As an example of why, consider a case elsewhere in his performance where Rev. Wright used a word sequence that clearly does involve two voiceless stops across a word boundary: "They have a different person to whom they are accountable".

Here's the acoustic picture:

Again, the /t p/ sequence yields just one closure and just one aspiration. And in this case, the closure is again about 50 to 55 milliseconds long.

In comparison, there's a nearby phrase "… based on sound bites, based on polls …", in which he says a word sequence ("on polls") where we know that a word-final nasal is followed by a word-initial voiceless stop.

Here's the acoustic picture:

In this case as well, the closure is between 50 and 55 milliseconds long.

We can't conclude anything for sure from one example of each category, and I don't have the time this morning to do a larger instrumental analysis of the Rev. Wright's speech. But these examples are enough to suggest what I expect, on other grounds, that we'd find: the acoustic distributions in fluent speech of the patterns

V N C # C V vs. V N # C V [where V="vowel", N="nasal", C="voiceless stop"]

are going to overlap enough that the case we started with — "think coming" vs. "thing coming" — will often not be clearly assigned to one category or the other.

[If you'd like to see the broader context of this passage, it's at about 3:28 of this video.]

etaoing said,

May 3, 2008 @ 1:23 pm

wow. I had always thought that "another think" was the mistake.

David said,

May 3, 2008 @ 2:36 pm

I would think that the "thing coming" version would be voiced all the way from the end of the [θ] to the [k] in "coming" while the "think coming" version would have a voiceless space between the [k] of "think" and the [k] of "coming".

[myl: (1) What do you mean by the "between the [k] of "think" and the [k] of "coming"? The sound stream of speech isn't a sequence of phonetic "beads on a string", with spaces between them. (2) Please examine the two cases "different person" and "on polls", discussed above, and explain how your idea applies to that contrast. Or supply some other examples.]

Garrett Wollman said,

May 3, 2008 @ 4:41 pm

I would mildly dispute your claim that 'No fluent native speaker of English would release the final /k/ of think in “think coming”'. I certainly think I am a fluent native speaker of English, and I definitely do so — probably more so in this situation, since the "think" version of the idiom is not part of my idiolect, so I pronounce it much more carefully. (Whereas I do prononounce the analogous "pink Cadillac" in precisely the way you expect.)

Unless the speaker were being similarly careful, I doubt I would ever *hear* the "think coming" version.

Arnold Zwicky said,

May 3, 2008 @ 6:20 pm

To Garrett Wollman: you're reporting on what's often called "hyperarticulate speech". Mark was describing ordinary connected speech.

Garrett Wollman said,

May 3, 2008 @ 10:04 pm

@Arnold Zwicky: I suppose my point was that I would not utter "another think coming" in "ordinary connected speech" (despite being a fluent native English speaker); it is too jarring. (It's only very recently that I even noticed this form; a year ago I would have assumed it to be a mere error and mentally corrected it.)

[myl: If you use "another thing coming" instead of "another think coming", then your pronunciation of the latter phrase isn't really relevant to the discussion. As a more relevant contribution, please record and send to me, say, Isaiah 50:3 "I clothe the heavens with blackness, and I make sackcloth their covering."

If you release the final /k/ of "sack" in a fluent rendition of this sentence, I'll be very happy to agree that you're right. But I'll also be very surprised.]

Garrett Wollman said,

May 4, 2008 @ 12:54 am

@myl: My pronunciation of the phrase was relevant to your overbroad claim that 'No fluent native speaker of English would release the final /k/ of think in “think coming”', with which I disagree. (And that was my sole, and very specific, point.) If you wish to reword that as "No fluent native speaker of English who uses the 'think' variant of this idiom would release the final /k/ of think in 'think coming' in ordinary connected speech", by all means, go ahead. I pronounce "sackcloth" in exactly the way you expect (as I noted was also true of "pink Cadillac" above).

[myl: Call it "no native speaker of English would release the final /k/ of think in a fluent pronunciation of 'think coming'" — since that was the point to start with — and I'll accept the quibble.]

Steve Cotler said,

May 4, 2008 @ 2:39 am

I suggest that meaning should trump pronunciation. Because Rev. Wright starts his warning, "If you think I’m going to…", he implies that will be a consequence to your action. The consequence is clearly (to me) that your "think" will be changed. So you'll have "another think coming."

Mark Liberman said,

May 4, 2008 @ 6:54 am

@Steve Cotler: I'm afraid that the facts trump your idea. As discussed in the earlier post linked to above, the 1919 citation in the OED for the use of "another thing coming" uses exactly the same frame:

1919 Syracuse (N.Y.) Herald 12 Aug. 8/3 If you think the life of a movie star is all sunshine and flowers you've got another thing coming.

That's because the frame is part of the expression. And if you search the web, you'll find that the many people who see the expression differently think that you've got another thing coming, namely the discovery that you're wrong.

Your version of the expression (which is also mine) makes sense. But so does theirs.

Josh Millard said,

May 4, 2008 @ 10:51 am

(Forgive the sidebar, but:

“think” [θɪŋk]

“thing” [θɪŋ]

Huh. Not θiŋk? θɪŋk as in θɪŋ, "thin", then? Do I have a nutty regional pronunciation, or do I need to take a phonetics course (yes, actually), or am I just bad at IPA (also likely)? This google search doesn't turn up much, and there are cites for both forms but from different sources on this dictionary.com page.)

[myl: Hi Josh — I don't θɪŋk I understand the question, but it seem likely that there's some lack of clarity about the International Phonetic Alphabet. You could start with the Wikipedia entry, and maybe the page giving an IPA chart for English.]

Josh Millard said,

May 4, 2008 @ 10:52 am

(That'd be this dictionary.com page.)

Arnold Zwicky said,

May 4, 2008 @ 11:36 am

To Josh Millard: the "pronunciations" given in dictionaries are almost never in IPA, but in transcription systems devised for each dictionary — usually based on the letters of the Latin alphabet, plus diacritics. You have to consult the pronunciation key for each dictionary to see what the symbols stand for (and since the keys use keywords rather than phonetic descriptions, they are often useless for many readers, since the keywords themselves vary in pronunciation from speaker to speaker).

A further complication: the vowel in what is spelled INK does vary from dialect to dalect, from what is clearly IPA [ɪ], through higher variants, and up to IPA [i] for some speakers. (In addition, there is word-to-word variation for some speakers.)

Sissy said,

May 5, 2008 @ 11:59 am

It's an expression I don't recall hearing used by anyone I know, and in fact the only reason I know it all is because in 1982 Judas Priest released a (in the metal crowd at least) famous song called "You've got another thing coming". So among the metalheads it is, and will always be, 'thing,' etymology be damned.

Josh Millard said,

May 5, 2008 @ 12:50 pm

Ah, thanks, you two. So it looks like the answers to my questions above are indeed "yes, actually", "also likely", and "don't foolishly presume consistent phonetic markup from dictionary to dictionary" to boot.

Curious about the variation in INK; it doesn't surprise me at this point, but I've just never noticed (I won't dare say 'encountered') that one in action.

Arnold Zwicky said,

May 5, 2008 @ 2:00 pm

To Josh Millard re the variation in INK: I discovered this when I started teaching intro linguistics, and in transcription exercises some students transcribed words like "think" with an i instead of an ɪ. At first I thought this was just an error in the use of the symbols, but then the students pronounced the words for me, and by golly they really did have raised variants. The word "think" was particularly likely to have a raised variant.

Now the complexity: the exercise was to do a *phonemic* transcription, and it's likely that for these speakers the raised vowels were allophones of the phoneme /ɪ/ (even though they were phonetically in [i] territory). That is, mentally their vowel in "think" was "the same as" their vowel in "thin", and if I'd asked them whether these vowels were the same *before we got into phonetics* they probably would have said they were. But once they started listening to their actual productions, they began hearing all sorts of subtleties (like the difference between the vowels of "seat" and "seed"), and they correctly perceived the closeness of their vowel in "think" to their vowel in "teen".

Mark Liberman said,

May 5, 2008 @ 3:07 pm

One more point on INK: note that there's a contrast between e.g. "kin" and "keen", but no corresponding contrast between "king" and "keeng". Since this contrast in vowels is generally absent before velar nasals in American English, raising the vowel of "king" doesn't risk any misunderstanding. That wouldn't stop anyone anyhow, but still…

Tim McKenzie said,

May 6, 2008 @ 2:07 am

My dialect is wildly different from Wright's, but when I say "thing coming", my [ŋ] is much longer (and possibly my [k] shorter) than when I say "think coming". Unfortunately, the audio output on my laptop is bust at the moment, so I can't easily record these and try to see the difference in the waveforms. (And also, I can't listen to Wright's speech.)

I'm not sure that your "on polls" example is parallel enough, unless his /n/ has been produced as [m] in that context. His [ŋ] and [k] are presumably produced in the same place as each other, as well as [n] and [t] in "different person".

James Wimberley said,

May 6, 2008 @ 6:49 pm

A digression. I'm puzzled by "kluge", pronounced Ms Moss-Coane to rhyme with "stooge".

1. I thought the geek usage was "kludge" as in "smudge".

2. Since "klug/e/er" is a regular and common German word (=clever), and the name of a well-known Nazi general to (jack)boot, the educated reader will surely try to pronounce the neologism as in German, with a hard g, like "Lüger".

What's going on?

John Cowan said,

May 6, 2008 @ 7:36 pm

I discovered the [i] variant of -ing when I transcribed the well-known sentence "We don't need no steekeeng badges", and someone (from the American West, I think) questioned the purpose of the second "ee". I was quite surprised.

James Wimberley:

See http://www.catb.org/~esr/jargon/html/K/kluge.html and http://www.catb.org/~esr/jargon/html/K/kludge.html (in that order) for a full account of the kluge/kludge confusion, now extremely entrenched.

Lastly, the name Lüger is common enough, but the inventor of the pistol was Georg Luger, and it is called the Luger after him.

Josh Millard said,

May 6, 2008 @ 7:41 pm

Pronunciation (and spelling, even) of "kluge" varies from geek to geek, and isn't a settled matter among those inclined to argue. (I prefer the "klooj" pronunciation.)

There's a Jargon File entry that covers some ground on this.

I've never met an (American) computer geek who pronounces it as if in German, and I've known several who've been avid students of German.

John Cowan said,

May 6, 2008 @ 7:56 pm

OBTW, do "thing coming" speakers now use it disconnected from the original frame, which is something like "if that is what X thinks, X has another think coming?" Or is there still an implicit reference to some existing state of belief that the speaker believes to be erroneous?

James Wimberley said,

May 8, 2008 @ 9:22 am

On kluge: Thanks Josh Millard. I suggest the key is in the Slavic word mentioned in the link article. клюҹ (n, key, clue) in Russian [attempt here to enter Cyrillic- may not work] would give the pronunciation in use, and the meaning is close enough. If the Polish is similar, the number of exiled Polish mathematicians working on early computers in Bletchley Park and Cambridge (Mass.) would explain the word's introduction. On this reading the connection with a German adjective is a false etymology as much as that with a Scottish word for toilet. As a Brit, I'll stick with kludge.

James Wimberley said,

May 8, 2008 @ 9:25 am

PS: thanks also to John Cowan.

David Walker said,

May 8, 2008 @ 3:04 pm

Didn't "The Wizard Of Oz" have someone in Oz tell Dorothy that she had another think coming, and soon after, ask her if she wanted to take her think now? "You have another one coming, you know." Or something like that.

mollymooly said,

May 8, 2008 @ 6:19 pm

The thing about "think" is that it doesn't occur as a noun in many contexts. The usual noun is "thought". "Another think coming", "have a think", and — at a stretch — "think tank" are the only ones I can think of.

mollymooly said,

May 8, 2008 @ 6:39 pm

To answer John Cowan's question, I grew up understanding it as "another thing coming" and was unaware of the existence of "another think coming" until well into adulthood. It's not part of my active vocabulary and I may only ever have heard it on television. To the extent that I analysed the expression at all, I think I interpreted the "other thing" very vaguely as some nemesis which would give the addressee cause to rue an arrogant belief. The expression is more a threat than a warning.

And as for "the pronunciations given in dictionaries are almost never in IPA" — this is true of American dictionaries, but British desk dictionaries now almost all use IPA symbols. The exception is Chambers, which retains respelling I think in deference to its Scottish origins: the same respelling pronunciation can be interpreted appropriately by Scots and Londoners in their different accents, where IPA dictionaries only give the South English pronunciation.

Rob Stryker said,

May 19, 2008 @ 2:05 am

David Walker:

That was Alice in Wonderland ;)

Dante said,

October 2, 2008 @ 4:15 am

There's a web service for showing segments from embeddable youtube videos.

So "it's at about 3:28 of this video" could be replaced with a link to http://splicd.com/t0fGH86DPag/208/588

Dante said,

October 13, 2008 @ 11:35 am

http://www.youtube.com/v/t0fGH86DPag&start=208&autoplay=1 might also be acceptable.

Dante said,

October 26, 2008 @ 6:24 am

OK, last chance: http://youtube.com/watch?v=t0fGH86DPag#t=3m28s

rick powers said,

September 2, 2010 @ 2:11 am

You've got another thing coming makes the most sense for this saying. It is the equivalent of conveying the following:

If you think you are getting a new car for your birthday, well, you have something else coming (hence, another thing is coming – and it is not motorized or nearly as expensive as a new car!).

If you think this, then you have another thing coming, because what you think is not the thing that is coming (true).

How can one have another think coming, if they already think they are right? They wouldn’t know to think again about the subject until they found out they were wrong, which at that time the other thing came – which was a sharp departure from the thing they thought was coming.

Warsaw Will said,

January 5, 2014 @ 6:49 am

Not to diss the thing version, but I've found two early think versions, from rather earlier than the OED lists, I think:

This is from The Packages Vol 9 of 1906:

"May be you think your factory is not a school. But if you do, you've got another think coming" (Google Books)

And this is from a book by Montague Glass, Elkan Lubliner, American , published in 1912.

"And if you think that this here feller Borrochson comes to work in our place, Scheikowitz, you've got another think coming, and that's all I got to say."

(You can find it at Project Gutenberg)

[(myl) The first LL post on the subject ("Another thing coming", 9/28/2007), linked in the original post, quotes an example from 1901; and the second post ("Have another think", 9/28/2007), also linked in the original post, cites an example from 1897.]