Washirweng

« previous post | next post »

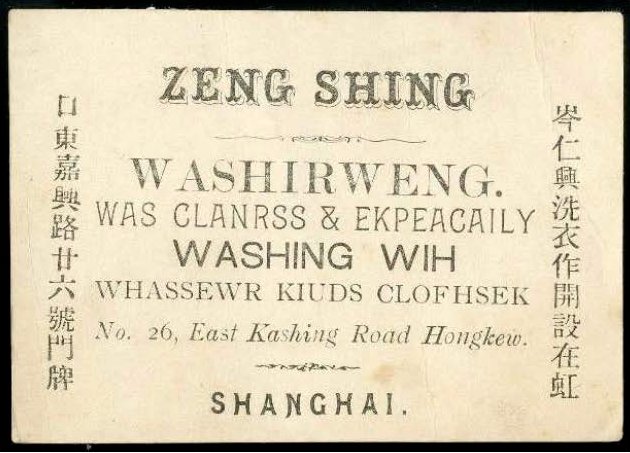

John Considine found this circa 1880 advertisement in the Hong Kong 2013 catalog of Bernard Quaritch (with the note that "We have not been able to locate any other example of this kind of trade card"):

The characters to the right and left of the English give the name and address of the laundry. Even though the right vertical line and the left vertical line are separated by the English wording, the sense of the Chinese runs on without a break. Notice that the first syllable (虹) of the Chinese name for Hongkew is at the bottom of the right vertical line and the second syllable (口) is at the top of the left vertical line. The Chinese is of no use in figuring out the mangled English.

I have posted this under "Lost in Translation", but it's not really a problem of mistranslation. It's hard to say exactly what configuration of circumstances resulted in what is printed on the card. Perhaps a Chinese-speaking compositor was trying to select Roman type which would correspond to a written text in front of him, but, not being familiar with the language, he had no idea what words he was supposed to spell and could only approximate what he was seeing. Language Log readers who are more clever than I may be able to come up with other scenarios that better account for what is found on the card.

Faith said,

March 26, 2014 @ 10:04 pm

Perhaps the last line is meant to read "whatever kinds of clothing"?

It puts me in mind of a story about Yiddish typography. In Vancouver, where I live, there was a Yiddish magazine published in the 1920s and 30s. The publisher bought a Yiddish font and gave it to a non-Jewish, English-speaking typesetter to use. He assigned each letter a number. He then would re-write his text using numbers instead of letters. The typesetter would use the numbers to figure out which letters went where. (The result was actually pretty good.) This story was told by the editor to the Canadian archivist David Rome, who told the librarian-book historian Brad Sabin Hill, who told me.

Bobbie said,

March 26, 2014 @ 10:33 pm

Here is my guess:

Washing

Dry Cleaners and Especially

Washing with [of]

Womens' Kid Gloves

Jenny Tsu said,

March 26, 2014 @ 10:44 pm

My guess is that a beginning, only partially-literate English speaker tried his best to write down letters that corresponded to the sounds he (kind of) knew. This is if I assume the English words are supposed to say something like:

"Washering (?)

Wash cleaners & especially

Washing with (white?)

Whatsoever kinds [of] clothes"

Additionally, it's also possible that this was compounded with the more usual variety of simple typographical errors introduced by the printer, like u for n in the word "kinds". As for the odd positioning of the Chinese text, that's easy to explain in a general sense if not in a specific sense – I regularly see all kinds of "creativity" coming from unsophisticated, local printers in Shanghai and just about everywhere else around the world.

julie lee said,

March 27, 2014 @ 12:19 am

Maybe

"Washirweng" is "Wash Ironing"?

Simon P said,

March 27, 2014 @ 1:41 am

I think the story of a Chinese typesetter basing it on a hand scribbled note sounds plausible. Not being used to cursive writing, and not knowing English, he tried his best to guess what lettres were on the note.

maidhc said,

March 27, 2014 @ 3:09 am

Strange that the address is good though. I think Simon P has it. The address was printed but the main text was written in cursive. If you take the suggestion from julie lee it might fit a cursive interpretation.

I can read Cyrillic fine if it is printed, but I'm useless at reading cursive. I can see some Chinese printer being the same way with English.

Stephan Stiller said,

March 27, 2014 @ 4:13 am

@maidhc

What I'm about to say is obvious (and you and many others will likely know this), but I've never encountered it in written form. So I might as well …

In cursive writing, there is so much ambiguity (because penstrokes are simplified, contracted, or omitted, letters are often just hinted at, letters are forgotten) that one needs what NLP (natural language processing) researchers call a "language model": knowledge of what is to be expected in the language. This includes statistical knowledge about letter frequencies, knowledge of what co-occurs in context, knowledge of which words exist, and so on. Without such knowledge, deciphering cursive writing can be hopeless.

leoboiko said,

March 27, 2014 @ 4:30 am

@Faith:What you described is literally a "character encoding", a predecessor to today's computer-based ones.

Dennis Paul Himes said,

March 27, 2014 @ 8:30 am

Are you sure it's English that's being mangled, and not Dutch or German?

julie lee said,

March 27, 2014 @ 10:11 am

The "clohfsek" probably stands for "clothes etc". , the "etc" meaning socks, sheets, pillowcases, towels, dishclothes, hats, etc. In cursive "etc" can look like "ek".

Whoever wrote the line probably copied the words from a dictionary without knowing English, and gave it to a typesetter who didn't know English. What impresses is the confidence and brio with which the lines are printed.

RP said,

March 27, 2014 @ 10:54 am

@Dennis,

It looks more English than German to me. My Dutch is very limited. However, it is worth noting that Britain, France and the US were the three imperial powers with "concessions" in Shanghai.

Mitch said,

March 27, 2014 @ 11:03 am

@Faith – what you describe is a scheme still used today, in the making of tombstones and other markers with Hebrew letters

BZ said,

March 27, 2014 @ 11:23 am

I didn't recognize this as English. Not a single word, except "washing". That's got to be a new record of incomprehensibility for mangling on signs.

Neil Dolinger said,

March 27, 2014 @ 12:08 pm

When I saw the first line "WASHIRWENG" I remembered that many years ago one of my students in Shanghai had the surname Weng. While that is not the rarest of surnames, it was new to me, so I looked it up in my dictionary. Aside from its use as a surname, this 子 also means "old man". So maybe this ad was for an old gentleman who took in washing.

Washin' it old school!

BobW said,

March 27, 2014 @ 1:01 pm

@ Julie Lee – I think you have it there – &tc. was common back in the day.

Stephan Stiller said,

March 27, 2014 @ 1:11 pm

@BobW

Or "&c" (or "&c."; not sure how they did periods back then).

julie lee said,

March 27, 2014 @ 4:32 pm

@BobW,

glad you agree. My guess is

"WASHING WIH"

stands for "WASHING WITH", introducing the next line (all kinds of clothes and stuff).

Brendan said,

March 27, 2014 @ 4:54 pm

Could "CLOFHSEK" be a garbled print form of a handwritten "CLOTHIER?"

Richard Futrell said,

March 27, 2014 @ 7:12 pm

This is an extreme example, but in my experience this kind of thing isn't too uncommon in China. I guess when people aren't familiar with the Latin script they're likely to mess up the letters. For example, in Beijing I saw a number of fire hydrants marked EIRE HYBDANT.

Andrew McCarthy said,

March 27, 2014 @ 8:26 pm

Is it possible that "washirweng" means something like "washerman?" It seems to be separated from the rest of the garbled message by a period, and as it comes immediately under the owner's name, perhaps it is a job title.

In which case the message might read something like:

Zeng Shing

Washerman.

Wash cleaners and especially

washing with

whatever kinds clothing.

Neil Dolinger said,

March 28, 2014 @ 11:19 am

I am curious about one element in the address. The English version states that this business is located in the "Hongkew" district. In MSM the corresponding characters would be pronounced "Hongkou" (sorry folks, I only know Pinyin – someone else will have to take a crack at the IPA). In Wu topolects, would 口 kou be pronouced more like English "kew" / "cue" or more like MSM "kou" / English "co"?

Michael Rank said,

March 28, 2014 @ 3:45 pm

That laundry card was going for £120/HK$1,500. Worth holding on to modern Chinglish ephemera…

Karen said,

March 29, 2014 @ 9:14 pm

I vote for the someone-who-couldn't-read-cursive hypothesis.

Take ekpeacaily. If the writer's s had a bit of a curl on the top it would have the same topology as a cursive k, and though someone who can read cursive wouldn't be confused, someone who couldn't might decide it must be a misshappen k. Then for the acail part, the writer may have rendered ciall so it was just a run of loops and the dot for the i could easily end up over a different letter when you toss it in after you've written the rest of the word.

So for that word at least I can come up with a plausible letter-by-letter explanation of how it is misread cursive. I don't see exactly how to do the other words, but that is partly because I don't know what words they were supposed to be.

Ching-Tung Huang said,

March 30, 2014 @ 7:39 am

Let's see what these Chinese characters means:

岑仁興: maybe it's owner's name.

洗衣作: laundry

洗=washing, 衣=clothes, 作 is an archaic way to say a store, equal to 店 (store).

開設: business place

在: at

虹口東嘉興路廿六號: an address of Shanghai. Its translation is correct.

門牌: address, location

Hope this helps a little.

Rachel said,

March 31, 2014 @ 3:49 pm

My personal favorite example of handwritten-to-type mistakes: I once saw a sign in Taiwan that advertised classes in MICVOSOFT WOVD. This clearly resulted from a typesetter being unable to distinguish between a handwritten v and r. (Many Taiwanese people write both as a small downward-pointing caret, with a minuscule or nonexistent difference in the angle and curve of the right-hand side.)

Kate Gladstone said,

March 31, 2014 @ 11:53 pm

The numbers-for-letters system of transcribing a foreign script usually works well, but a calligrapher friend of mine ran into problems with it, the first time she had to calligraph a document in Hebrew, a language she does not know. Although she had practiced its alphabet, somehow she had not remembered that this script runs right to left. Her entire copy was, as a result, beautifully penned nonsense which had to be done all over.

marie-lucie said,

April 3, 2014 @ 2:38 pm

Before washing machines were standard household appliances, most of the laundry of European urban dwellers was done professionally in specialized establishments, especially the heavy work for large items such as sheets and tablecloths, and other "white" items, made of linen, which needed to be boiled, hung to dry, and pressed, all of which took not only time and effort but space and specialized equipment and handling. Surely Zeng Shing was not the only person operating a laundry patronized by Europeans in Shanghai at the time, so words for the same services offered must have been written (more or less correctly) on other documents, whether bilingual or not. I understand that the card here is the only known surviving example of its kind, but similar or equivalent words must have been written elsewhere, perhaps painted on shop doors, etc., as well as mentioned in sundry writings dealing with daily life, such as personal journals. The emphases on clothes on the card may mean that Zeng Shing's establishment specialized in washing clothes rather than household linens, especially delicate items such as the thin, lace-trimmed or embroidered women's and children's clothes popular among upper-class Europeans at the time. Perhaps someone has done research on "Chinese laundries catering to the 'concessions' in Shanghai, 18**-1920" ??