Translation as cryptography as translation

« previous post | next post »

Warren Weaver, 1947 letter to Norbert Wiener, quoted in "Translation", 1949:

[K]nowing nothing official about, but having guessed and inferred considerable about, powerful new mechanized methods in cryptography – methods which I believe succeed even when one does not know what language has been coded – one naturally wonders if the problem of translation could conceivably be treated as a problem in cryptography.

Mark Brown, "Modern Algorithms Crack 18th Century Secret Code", Wired UK 10/26/2011:

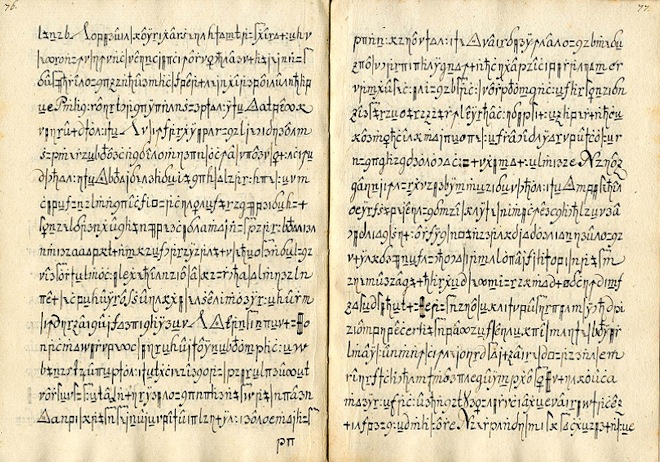

Computer scientists from Sweden and the United States have applied modern-day, statistical translation techniques — the sort of which are used in Google Translate — to decode a 250-year-old secret message.

The original document, nicknamed the Copiale Cipher, was written in the late 18th century and found in the East Berlin Academy after the Cold War. It’s since been kept in a private collection, and the 105-page, slightly yellowed tome has withheld its secrets ever since.

But this year, University of Southern California Viterbi School of Engineering computer scientist Kevin Knight — an expert in translation, not so much in cryptography — and colleagues Beáta Megyesi and Christiane Schaefer of Uppsala University in Sweden, tracked down the document, transcribed a machine-readable version and set to work cracking the centuries-old code.

On Kevin's home page, along with a lot of other neat stuff, you'll find a link to a page on The Copiale Cipher, where in turn you'll find links to various versions of the original document, to many discussions in the popular press, and to a couple of technical and scholarly papers, including Kevin Knight, Beáta Megyesi, and Christiane Schaefer, "The Secrets of the Copiale Cipher", Journal for Research into Freemasonry and Fraternalism 2012.

Victor Mair said,

November 19, 2012 @ 6:52 am

The contents are very strange:

"The researchers found that the initial portion of 16 pages describes an initiation ceremony for a secret society, namely the 'high enlightened (Hocherleuchtete) oculist order' of Wolfenbüttel. [VHM: There's a very famous old library there.] The document describes, among other things, an initiation ritual in which the candidate is asked to read a blank piece of paper [VHM: !!!] and, on confessing inability to do so, is given eyeglasses [VHM: Mind you, this document is thought to date between 1760 and 1780, though glasses existed centuries before this time] and asked to try again, and then again after washing the eyes with a cloth, followed by an 'operation' in which a single eyebrow hair is plucked."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copiale_cipher

Now, on to Linear A and the Phaistos Disk!?

richard howland-bolton said,

November 19, 2012 @ 7:04 am

Wow! And they didn't even have Transitions® Lenses back then!

markonsea said,

November 19, 2012 @ 7:07 am

"… Try reading again, the master says, replacing the first page with another. This page is filled with handwritten text. Congratulations, brother, the members say. Now you can see."

It's a ritual!

I've been waiting nearly 50 years for someone to tell me what the Phaistos Disk says. Hope it's not just an ad for payday loans or the like!

Ralph Hickok said,

November 19, 2012 @ 8:27 am

I thought at first that "oculist" must be a typo for "occultist," but now I see that it isn't.

Mike said,

November 19, 2012 @ 9:40 am

I vote for the Indus Script next.

I looked up Wolfenbüttel, and notice that its economy consists of two things: a university, and a distillery. That alone should have been enough to help decipher it.

Dan Lufkin said,

November 19, 2012 @ 9:48 am

Urim & Thummim, perhaps? More explication here.

Dan Lufkin said,

November 19, 2012 @ 9:55 am

And here, too, of course. How could I have forgotten? Fugue state, I think it's called.

Robert Coren said,

November 19, 2012 @ 10:47 am

And while we're at it, how about the writings found on Easter Island?

Circe said,

November 19, 2012 @ 1:03 pm

Mike: "I vote for the Indus Script next."

isn't the problem there that there is a surprisingly small corpus to work with? I agree it is very unlikely that given their achievements in other fields and the scale of their trade and extent, the Indus people did not have some sort of written language, but the paucity of text probably does cast some doubt.

Jimbino said,

November 19, 2012 @ 2:30 pm

I'd like to see someone come up with a list of cusswords or phrases from all the possible languages that could be used on Amerikan vanity plates.

How do you say "Kiss my ass" in Klingon, for example?

Pompeius said,

November 19, 2012 @ 2:36 pm

While the codex is certainly interesting, I'm not sure the quote by Mr. Wiener is applicable here. After all the team correctly guessed that the codex was written in German, they wouldn't have gotten anywhere if it were Navajo.

Aelfric said,

November 19, 2012 @ 3:55 pm

The Voynich Manuscript should OBVIOUSLY be next, even though I am 95% convinced it's just nonsense designed to look like a language. I would be happy to be proven wrong, however!

Jason said,

November 19, 2012 @ 4:16 pm

More details here: http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/11/ff-the-manuscript/all/ .

This was definitely cryptology, not machine translation (Wiener quote notwithstanding.) The leader of the team, Kevin Knight, was an expert in machine translation (they would have broken it even faster if they'd hired an actual cryptologist!) Technical details are hard to excavate from the article, but it appears to have been a one-to-many (polyalphabetic) substitution cipher, one in which each symbol (letter) of the plaintext is mapped to one of several possible ciphertext symbols. (The ciphertext symbols were polygraphs, or sequences of multiple symbols, to complicate things slightly.) This kind of cipher requires a reasonable amount of ciphertext in order to perform the statistical analysis required to break it, which, fortunately, the team had.

They did not know the original language the text was written in. They identified digraphs in the code and, since this kind of code defeats simple letter frequency analsysis, probably used digraph distribution statistics and entropy analysis to identify the probable language as German. They then used a hill-climbing algorithm to gradually converge on the correct substitution table (the key). The one snarl was the distractor (null) letters in the cipherstream, which led them down the garden path for a while, but once they identified the roman letters as junk symbols, they were on the right track. The last part was identifying the special ideograms in the text, which required hermeneutics more than anything else.

Far more interesting than anything Robert Langdon has ever done. There appear to be no crazed self-flagellating albino monks on Kevin Knight's trail, though. And it appears this is old news, from October last year, which Wired has only just picked up on, using the science journalist's license to breathlessly report as an exciting new result work that can be years or even decades old.

Jason said,

November 19, 2012 @ 4:22 pm

@Aelfric <- "The Voynich Manuscript should OBVIOUSLY be next, even though I am 95% convinced it's just nonsense designed to look like a language. I would be happy to be proven wrong, however!"

I am virtually certain that Mr. Knight's techniques were all basic cryptology, all of which have been performed on the Voynich manuscript without the slightest bit of success. Most people believe it's either meaningless, or possible an early conlang (constructed fictional language, a la Tolkien). Either way, it's probably unbreakable.

wren ng thornton said,

November 19, 2012 @ 4:55 pm

It is worth noting that Kevin Knight's father is part of an amateur cipher/cryptologist community (who trade crypto-ed messages and attempt to solve them without modern tools), and he occasionally enlists his son's help to figure out what language the given cipher is in (and nothing else! lest it ruin the fun). And aside from his work in computational linguistics, Kevin too has long had a side interest in cryptological puzzles (including not only the Copiale Cipher but also the Voynich Manuscript). He tends not to discuss it much, what with these texts often being associated with crackpots, but he gave a talk about all this at the Turing Centenary Symposium at NASSLLI 2012.

Andy Averill said,

November 19, 2012 @ 8:49 pm

@Jason, if I ruled the world, I'd require science journalists to wait at least a year after a study is published before they write about it. Then they can be as breathless as they want.

Chris said,

November 19, 2012 @ 10:18 pm

@Jason:

After reading the article you linked to, I get the impression that the Copiales cipher was largely one-to-one, not one-to-many. Excluding the few symbols representing entire words and the Roman letters used instead of spaces between words, it looks as though each letter in the cipher may have corresponded to just one letter of 18th century written German. As far as I can see, the only instance of "one-to-many" correspondence mentioned in the article is the three symbols matched to the letter "i". I know that Germans once wrote "y" and "i" in places where modern German orthography requires "i" only. I'm not sure why there would be a third symbol corresponding to modern German "i" but then I know only a little about 18th century German spelling conventions.

In another example of spelling changes, the article mentions that a word in the cipher was decoded as "candidat". This would be Kandidat in modern German.

Roger Lustig said,

November 19, 2012 @ 10:41 pm

Well, this former resident of Wolfenbüttel has been in stitches all day. I wonder whether the place was especially enamored of secret societies and all that pomp? The Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft (a century earlier, and very much linguistically aware) comes to mind.

@Chris: I, Y and J had overlapping functions in German orthography, including the y often being typeset as an ij. Even today, a lot of people write capital I and capital J identically.

@Jimbino: how do you not say "kiss my ass" when speaking Klingon?

Allen said,

November 20, 2012 @ 2:32 pm

> Most people believe it's either meaningless, or possible an early conlang

http://m.xkcd.com/593/

David Eddyshaw said,

November 20, 2012 @ 2:52 pm

I actually *am* an oculist, and would be delighted to explain all of this to you, but then of course I would have to kill you. All.

wren ng thornton said,

November 20, 2012 @ 4:36 pm

@Chris: It's one-to-many in the sense that for each input character to be ciphered, the author has the choice of many different output characters. That is, the ciphering operation is not a (mathematical) function. Conversely, the unciphering operation is not an injective function.

This is, of course, different from the sense that a single input character is mapped simultaneously to a collection of output characters. There were some cases of the converse of this, where certain input digraphs (and trigraphs?) were mapped to a single output grapheme; but, as you say, it was not especially prevalent (and is fairly predictable based on German orthography).

Tim said,

March 18, 2013 @ 4:14 pm

Amazing how far "machine" translation has come over the years. As a graduate of the University of Southern California Viterbi School of Engineering, and having casual knowledge of Kevin Knight, this was fascinating.