Graphically snuckward

« previous post | next post »

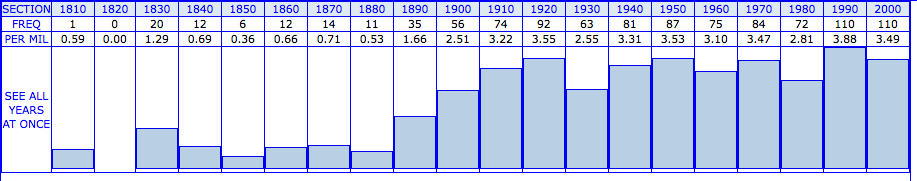

Following up on yesterday's Snuck-gate post — and on "Snuckward Ho!", 11/29/2009 — I thought I'd take advantage of Mark Davies' new Corpus of Historical American English to provide a graphical summary of the origin and progress of the strong past tense of sneak.

COHA comprises about 400 million words of text. In principle, it should be organized as 20 million words in each of the 20 decades from 1810 to 2009, but in fact the per-decade counts currently start lower, and don't pass 20 million words until 1900. A detailed list of sources is available here. The per-decade collections are of course not perfectly balanced, since the sorts of available texts have changed so much over the past two centuries; but Mark has tried to create the best balance he can.

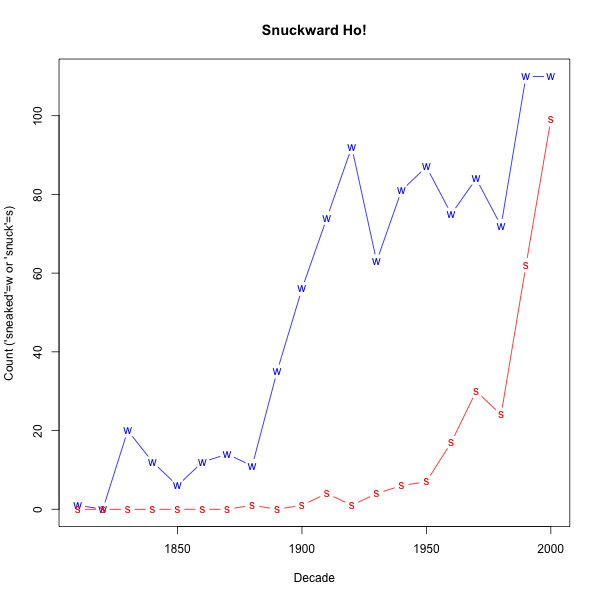

The first thing to note is that the frequency of both forms has increased over time, starting with a "sneaked" increase in the late 19th century:

This is true even if we look at the frequency e.g. of sneaked per million words:

It's not clear whether this is a linguistic change (that is, a change the words that people choose to express a certain concept) or a cultural change (that is, a change in the concepts that people choose to write about).

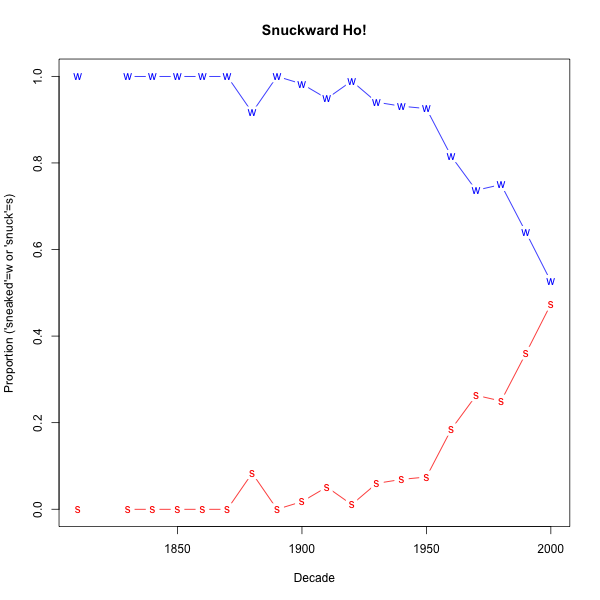

However, there's also a clear snuckward trend, as we expect:

And it seems that this is a linguistic trend rather than a trend of some other sort. Given that American writers choose to write about the concept of sneaking, and choose to use the lexeme sneak, and choose to frame a sentence using the past tense of a verbal form of that lexeme, they're becoming increasing likely to express that form as "snuck" rather than "sneaked".

Ray Girvan said,

June 19, 2010 @ 4:03 pm

You can also do a very rough-and-ready corpus search with Google News, which even does a nice graph. As you say, the meaning's not clear (e.g. word coming into language / newspapers lightening up about its use / whatever) but it certainly shows a dramatic increase of use.

Terry Hart said,

June 19, 2010 @ 4:14 pm

Allow me to sneak in a(n) unrelated point…

Is "starting with AN 'sneaked' interest" as written above correct, or should it be "starting with A 'sneaked' interest"?

I never realized that was a rule until reading this post from yesterday: http://kfmonkey.blogspot.com/2010/06/one-rule-i-refuse-to-follow.html

[(myl) Actually, you "never realized" correctly, and should return as soon as possible to a state of not believing that the cited post makes the slightest bit of sense.

In order to help you out, here's a note from DP that arrived in this morning's email:

I was going to turn this into a separate post, but since you brought it up…

I can testify that the reason I originally wrote "an increase in 'sneaked' in the late 19th century". THen I noticed the two stacked up "in" phrases, and so I re-arranged the words — but carelessly neglected to modify the form of "an". I suspect that some editing process of this kind, in which the modifier is stuck in later and the form of the determiner isn't changed, is responsible for the most if not all of the examples that Michael Alan Nelson (incorrectly) generalizes from.]

A. S. Trotter said,

June 19, 2010 @ 6:32 pm

Everyone I know here in North Carolina says "snuck", as far as I know. As for the reason "snuck" was the obvious choice, over, say "snoke" or "snought", (or "snake", which somehow doesn't sound strange either)…I wonder if the verb "slink" had something to do with it? Is there any debate over whether "The snake slunk through the grass" is properly formed? Both have very similar sinister connotations. ("Stunk" seems to fit in that mold as well).

Ray Dillinger said,

June 19, 2010 @ 7:09 pm

It is surprising to me to see an irregular "strong" form gaining ground where a correct regular form had widespread acceptance.

Irregular forms are part of the "cognitive load" of a language, and my default assumption is that most words get regularized over time as speakers "lighten the load" by adopting a simpler model of language. Meanwhile, this naive supposition says, other irregular forms creep in, from foreign borrowings, phrases adopted as words, phrases becoming grammatical particles, etc.

This trend with "snuck" (my spell-checker reports that it is misspelled) indicates that my assumption about how language evolves was wrong. People are here abandoning an established regular form for an invented irregular one, and this suggests that the irregularity serves some linguistic purpose of which I am ignorant. This is interesting and makes me curious.

Do irregularities give a language some property beneficial to the speakers? Is a certain amount of irregularity a way of giving the mind cognitive or structural "landmarks" or "handles" to work with? The implication that English, of all languages, didn't have *enough* irregularities to serve whatever mysterious purpose there may be seems nearly ludicrous. But is there another way to interpret the evidence?

I conjectture that a word must be reasonably common (ie, in the working vocabulary of most children) in order to be and remain irregular. Has "sneak" increased in usage sufficiently to cross a threshold?

jc said,

June 19, 2010 @ 11:10 pm

What strikes me is that people are calling this a "grammar" issue without being challenged. This means that they don't understand the difference between grammar and phonetics. The a/an pattern has nothing whatsoever to do with grammar, and we should be challenging (or educating) people who claim that it does. It's purely a phonetic alternation that has nothing to do with anything grammatical.

Next we're going to hear people treating the pronunciation of the -s suffixes (plural or 3rd-person singular) as a grammar issue. They'll try to make up grammar rules for when it's pronounced /z/, and people won't challenge them by pointing out that it's not a grammar issue at all.

Ya've gotta be ignorant of basic Linguistics 101 stuff to confuse phonetics with grammar.

[(myl) With respect, the a/an alternation is not exactly phonetics — I guess that technically, it counts as phonologically-conditioned allomorphy.]

Rubrick said,

June 19, 2010 @ 11:31 pm

Please do a similar analysis on the relative frequencies of "steaked" and "stuck".

John Cowan said,

June 19, 2010 @ 11:49 pm

Ray, you're basically right, but occasional wrong-way conversions (weak to strong) have happened in English, generally speaking under the pressure of analogy. "Sound-change operates regularly to produce irregularities; analogy operates irregularly to produce regularities" — in this case, irregular regularities. Other well-known cases, not always in all uses or in all anglophone regions, are help, show, dig, stick, spit, ring, shine, twug 'caught on, understood', and dove.

Rubrick said,

June 19, 2010 @ 11:57 pm

I guess "peaked/puck" would have made a more sensible joke.

Karen said,

June 20, 2010 @ 9:52 am

Just so I know I'm not losing my mind: "Other well-known cases, not always in all uses or in all anglophone regions, are help, show, dig, stick, spit, ring, shine, twug 'caught on, understood', and dove." This list contains both directions of change, strong to weak and weak to strong, yes?

Julio Sueco said,

June 20, 2010 @ 10:36 am

Gotta agree with JC, though I believe it's more phonological than phonetic. The slide to the bilabial after the vowel could create said "grammatical" errors during high speed writing. I am strictly Cartesian & I believe we think before we write. There is a myriad of phenomena at the language level occurring during writing that we forget we think and hear and produce vocal movements even when we are writing which tends to be a "silent" activity. try it yourself and feel how dangerously close the vowel to the bilabial nears an n which is a nasal sound. My 2 Swedish öre there.

Bill Walderman said,

June 20, 2010 @ 1:21 pm

Richard Hogg offers an intriguing suggestion that the "but" vowel (the vowel phonetically represented by an inverted "v") came to be perceived as an "ideophonic marker of past forms regardless of the vowel of the present tense," as exemplified by "dug," "struck" and eventually "snuck." I can add a very small piece of evidence for this hypothesis. About thirty years ago I noticed a friend of mine in rural southeast Alabama, along with various members of his extended family, using the form "crunk," with the inverted "v" vowel, as the preterite or past participle of the verb "to crank," meaning "to start" (either transitively or intransitively) with reference to an engine such as that of a car or bulldozer.

J.W. Brewer said,

June 20, 2010 @ 4:04 pm

There is apparently some controversy about the etymology of "crunk," in the sense of the style of rap-derived music mostly found in the American South, with one theory being irregular-past-participle-of-"crank" like Bill Walderman's suggestion (I would hypothesize in the sense of "cranked up" meaning excited and perhaps intoxicated and/or the sense meaning turn-up-the-volume-on-the-stereo), and another theory being a portmanteau of "crazy" and "drunk" (meaning much the same as the first proposed sense of "cranked up"). Some sort of loose analogy to "punk" (in the sense signifying a genre of music) may also be in the mix.

army1987 said,

June 20, 2010 @ 4:36 pm

@Terry Hart:

A few years ago I read something even worse in a newsgroup about Italian: someone complaining that everybody said un talent scout rather than the "correct" form uno talent scout (who nobody in the newsgroup had ever heard) — in Italian the singular masculine indefinite article is un except before some consonant clusters including /sk/ where it's uno, and that guy assumed that it's the head noun which matters rather than the immediately following word, but gave no reason whatsoever as to why he believed that.

Coby Lubliner said,

June 20, 2010 @ 7:15 pm

Another example of a strong past tense with "short u" is Dizzy Dean's famous "he slud into third."

John G said,

June 20, 2010 @ 11:25 pm

and the pressure to use the short u sound in the simple past may also be illustrated by the increasingly common 'sunk' in that tense. Also 'drunk' So it tends to overcome even strong alternatives.

Ben Hemmens said,

June 21, 2010 @ 7:13 am

Bet you could do the same thing for "shat" ;-)

Teresa G said,

June 21, 2010 @ 9:15 am

Just wanted to challenge the claim (made by jc) that phonology grammar. While it's true that in common usage "grammar" is usually interchangeable with "syntax", most linguists use the term more broadly to include all the (non-prescriptive) rules of how language works, whether they are phonological rules or syntactic ones or otherwise. So I would say that the a/an rule is most certainly a rule of English grammar, even if it has nothing whatsoever to do with syntax. And I would have thought this should have been taught in LING 101 :)

Teresa G said,

June 21, 2010 @ 9:17 am

Drat. I tried to use "less than" plus "greater than" to symbolize "not-equal to" in my post above, but this got removed as apparently resembling HTML mark-up. It should have read "…challenge the claim that…phonology is not equal to grammar"

Faldone said,

June 21, 2010 @ 9:49 am

And, FWIW, there was an OE verb snīcan, which was strong. Its past tense was snāc which should have come to us as 'snoke'. But then the present base form should have been 'snike', which Clarke-Hall cites in its entry for snīcan. I have never seen snīcan cited in any etymology for 'sneak'. I'm not sure what that means.

Jerry Friedman said,

June 21, 2010 @ 9:57 am

@John G.: "Honey, I shrunk the kids!"

exackerly said,

June 21, 2010 @ 1:24 pm

In another corpus, Google Books, not as scientifically weighted of course, I found 82,200 hits for "sneaked" before 1950, including an unknown number of books written in British English. "Snuck" only gets 1560 hits, mostly in passages that were clearly intended to mimic dialect.

So whatever the proportions were in spoken English back then, "snuck" was clearly not considered legitimate in written English. But HL Mencken includes it in his list of common verb forms in American speech (as of 1921).

Matthew Kehrt said,

June 21, 2010 @ 2:31 pm

@Faldone etymonline (which is not an academic source) gives the etymology of sneak as descending from OE snican directly rather than, say, being a cognate borrowed from Dutch later on. So, who knows how it ended up in the form it has.

Faldone said,

June 21, 2010 @ 3:48 pm

@Matthew Kehrt. It looks like it's a little short of saying it's descended from snīcan.

ohwilleke said,

June 21, 2010 @ 5:49 pm

I'm not sure that it is correct to call "snuck" a triumph of an irregular form over a regular form "sneaked." It might be more accurate to say that there are two regular forms, the suffix form and the ablaut form that have been competing over time.

The view that a suffix form is natural is associated with Latin inflection and may reflect the impact that Latin and French grammar had on the English language, particularly among the upper classes.

The rise of snuck coincides fairly closely with the demise of Latin as part of the core curriculum for the educated, and with the reduced importance of French instruction in schools.

There has been a countertrend of effective rhetoric writers who have argued that unsuffixed simple, Anglo-Saxon words are a more effective and easily understood way to communicate in the English language. This movement is a restorationist one. It seeks to return English to its pre-Romance language roots. Hence, the resurgence of ablaut forms rather than suffixed forms in polite conversation, in line with the long term trends in the English language.

John Cowan said,

June 22, 2010 @ 1:28 am

Karen: Including help was a brain fart on my part, as it is a strong-to-weak conversion. Show began weak and remains so in the preterite, but the past participle is strong. The remaining cases, dig, stick, spit, ring, shine, twig, dive are all true wrong-way conversions, ring being the oldest (13th century) and twig the newest (20th century). Unaccountably I put twig, dive in the preterite in my original post and left the rest in the plain form.

Faldone said,

June 22, 2010 @ 7:08 am

John Cowan: "The remaining cases, dig, stick, spit, ring, shine, twig, dive are all true wrong-way conversions …"

Shine is from OE scīnan, a Class I strong verb, 1st. preterit scān, 2nd preterit scinon, past participle scinen. Some will say that modern usage requires shine to be regular when it is transitive and irregular when it is intransitive.

“Snuck” sneaked in « Sentence first said,

June 23, 2010 @ 7:29 am

[…] Liberman runs a corpus analysis and shows graphically how "the frequency of both forms has increased over time . . . . However, there's also […]

ED said,

June 23, 2010 @ 1:02 pm

After recently rereading The Hobbit and The Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy, it stuck (!) out that both writers used "span" as the past of "spin", where I would only ever say or write "spun".

I also have the vague recollection that little kids will use "regularized" forms like "spinned" or "sitted" before they learn to use irregular forms.

I'm not sure how any of this relates to the present discussion but it seemed semi-relevant.

I Fruck Out « Literal-Minded said,

August 13, 2010 @ 3:11 pm

[…] past them. That reminded me of various discussions I've read about the word snuck, like this one at Language Log, and this one from Sentence First (which I linked to a few months ago). The interesting thing about […]