Technology is probably isn't destroying our humanity

« previous post | next post »

The "technology is destroying our humanity" trope has been around for thousands of years, certainly since the invention of writing devalued textual memorization. I wouldn't be surprised if there were analogous complaints about the invention of the spear.

The most overhyped version of this trope that I've ever seen was the 2009 "Twitter numbs our sense of morality and makes us indifferent to human suffering" scandal, where hundreds of media outlets wrung their hands over a study that had nothing to do with either Twitter or morality (see "Debasing the coinage of rational inquiry: a case study", 4/22/2009). Running a close second is the 2005 "emails, text and phone messages are a greater threat to IQ and concentration than taking cannabis" kerfuffle (see "An apology", 9/25/2005).

But the current "Access to Screens is Lowering Kids' Social Skills" paroxysm is offering some stiff competition to these classics in the anti-technology nonsense department.

Some of the media uptake: "Why Access to Screens Is Lowering Kids’ Social Skills"; "Study: Digital Media Erodes Ability To Read Emotional Cues"; "How digital technology and TV can inhibit children socially"; "Children Losing Social Skills in Digital Age?"; "Screen Time Makes Tweens Clueless on Reading Social Cues"; "Digital media erodes social skills in children"; "Kids losing social skills due to smartphones"; "Is smartphone making your kids anti-social ?";"Are Young People Losing the Ability to Read Emotions?"; "Technology-Obsessed Children Losing the Ability to Read Emotions"; and many more.

The scientific publication behind this: Yalda Uhls et al., "Five days at outdoor education camp without screens improves preteen skills with nonverbal emotion cues", Computers in Human Behavior, October 2014. Perhaps because it has apparently arrived from a couple of months in the future, this paper is Open Access, so you can read it for yourself.

And here's what you'll learn.

51 kids about 11 years old "spent five days in a nature camp without access to screens" (the Pali Institute); a control group of 54 kids spent the same period going to school, during which time they are assumed to have maintained their normal self-reported screen consumption of 1.1 ± 1.6 hours a day of texting, 2.1 ± 1.6 hours a day of watching TV, and 1.4 ± 1.4 hours a day of playing video games.

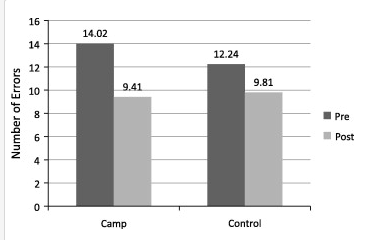

Before and after those five days, the subject took "the Faces subtests of the second edition of the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Behavior (DANVA2)", and "The Child and Adolescent Social Perception Measure (CASP)". Here are the results for DANVA2:

So the Camp group started out about 15% worse than the Control group, for some unexplained reason (maybe due to the rather different ethnic makeup of the groups?); after five days away from screens, they were essentially the same as the Control group (well, maybe 4% better). Both groups improved, probably due to a practice effect. The Control group didn't improve as much.This might be because their social awareness was fried by all that screen time, which is what we're supposed to believe. But it also might be because of a ceiling effect, or or it might be because they were less interested in the whole "take a test for science" thing than the kids who just spent five days at science camp; or it might be for some random reason, like the reason that the Camp group was 15% worse to start with ….

On the CASP test, the Camp kids' score improved from 26% correct to 31% correct, while the Control kids stayed flat at 28% correct.

Again, the Control kids did a little better in the beginning, but didn't improve as much. Again, this might be because of their screen time during those five days; or it might be (for example) because the Camp kids were all excited about science, or just generally feeling good; or it might be because the Control kids were jaded and worn out after being in school all week. (Note that there were no control tests of long division or short-term memory or anything else that might tell us about general alertness and commitment to the testing process…)

It would be fair to frame these results as Uhls et al. did in their paper's title: "Five days at outdoor education camp […] improves preteen skills with nonverbal emotion cues" — or maybe just "Five days at science and nature camp makes preteens better test takers". What absolutely is NOT true of these results is that "Access to Screens Is Lowering Kids’ Social Skills", or that "Digital Media Erodes Ability To Read Emotional Cues", or that "Screen Time Makes Tweens Clueless on Reading Social Cues", or that "Kids [are] losing social skills due to smartphones", or any of the other ways that the results have been reported in the popular media. (Only 22% of the Camp group and 26% of the Control group even had a cell phone of whatever type.)

It makes you wonder whether journalists and their editors in general lack the basic ability to read and think — maybe their interpretive abilities have been fried by all that screen time? The alternative explanation is that they just don't care, preferring to go for the click-bait and never mind the facts. The "go for the click-bait" theory is a variant of the suggestion I made a few years ago, that science stories "have taken over the place that bible stories used to occupy. It's only fundamentalists like me who worry about whether they're true. For most people, it's only important that they're morally instructive."

What would [journalists and their editors] say, if presented with evidence that they've been peddling falsehoods? I imagine that their reaction would be roughly like that of an Episcopalian Sunday-school teacher, confronted with evidence from DNA phylogeny that the animals of the world could not possibly have gone through the genetic bottleneck required by the story of Noah's ark. I mean, lighten up, man, it's just a story.

D.O. said,

August 29, 2014 @ 2:54 pm

I will take issue with reporting data as

If your standard deviation is larger than the mean (or even if smaller, but only by little) and quantity under study is non-zero by definition, it does not make sense to use it. Give median and interquartile range.

[(myl) Indeed. You should take it up with the statistics courses taught to social scientists (and by extension to journal editors and referees in the relevant disciplines), which tend to assume, counterfactually, that all distributions are normal, and that statistical methods assuming normality are therefore by default OK.]

TonyK said,

August 29, 2014 @ 5:10 pm

That thing about spears turned out to be true, though.

[(myl) You mean that weapons and other tools have made us less human? Less "natural" maybe, but I think most people would disagree about the connection to humanness…]

Gregory Kusnick said,

August 29, 2014 @ 6:32 pm

So where's the control group of kids who took their screens with them to camp?

[(myl) Uhls et al. write:

In choosing the control group, we considered other groups, such as an overnight camp that integrated screens into the daily activities, but we determined that the selection effects outweighed the benefits of matching on the overnight experience; in other words, children who are interested in these kinds of technology-oriented camps, and whose parents could afford the cost (e.g., currently, UCLA Tech overnight camps are approximately $2000 for one week), would not be a good match for children who were sent to an outdoor nature camp underwritten by a public school district.

]

Ken said,

August 29, 2014 @ 7:04 pm

No, the spear was hailed as the invention that would finally bring peace, by making combat so deadly that no one would ever again dare to start a war.

(Stolen from an old short story, except IIRC it was the bow and arrow in that one.)

Rubrick said,

August 29, 2014 @ 7:34 pm

The study I want to see is the one correlating headlines phrases as questions with complete poppycock.

Bob Ladd said,

August 30, 2014 @ 3:30 am

@Rubrick: The "Feedback" column in New Scientist raised exactly your point last month (the 19 July issue, to be precise), saying that the question mark at the end of a title or headline "begs the answer 'of course not'", and challenging readers to supply counterexamples. So far no real ones have been supplied.

"Feedback"'s phrase begs the answer is also relevant to earlier LL discussion of the expression beg the question, e.g. here and especially here.

Brett Reynolds said,

August 30, 2014 @ 6:49 am

Clearly what this shows is that the PROSPECT of going to nature and science camp is debasing our humanity.

Jerry Friedman said,

August 30, 2014 @ 9:49 am

Here I thought "1.1 ± 1.6" might be a typo.

MYL: Not to speak for TonyK, but I understood him as saying that spears made us, if not less human, at least more inhuman.

[(myl) Right. But isn't this one of those cases where (part of) the essence of X-ity is in-X-ity?]

Pcv said,

August 30, 2014 @ 11:43 am

Typo in the headline: Technology IS probably ISN'T…..

Jonathan said,

August 30, 2014 @ 12:23 pm

> "The study I want to see is the one correlating headlines phrases as questions with complete poppycock."

I don't know of any studies, but popular wisdom does have Betteridge's law of headlines.

Claire said,

August 30, 2014 @ 2:38 pm

It's all that screen time that journalists have, and all the time they spend on twitter. It makes them much worse at processing information and morally bankrupt.

James Wimberley said,

August 31, 2014 @ 1:10 pm

Tonyk: It was the bronze spear that did it. Achilles has one, you don't. Your easily-made stone-tipped spear is useless against it. So Achilles can get you to do what he says. He claims to be partly a god, which makes him less than human.

There are the ruins of a Chalcolithic village near Almeria in Spain. It is strongly fortified, in concentric circles; the forge is protected by the inner wall. Copper doesn't make good weapons, just cooking pots, mirrors and so on. The Chalcolithic didn't last long before somebody made the critical experiment with tin, and you had the iPhone of weaponry. So maybe it was the simple scarcity of something desirable that turned society violent, and hunter-gatherers are rarely peaceful. But it was bronze that made kings, in the Old World.

Joseph said,

September 1, 2014 @ 6:36 am

"The invention of writing devalued textual memorization" was mentioned at the beginning of this post. I vaguely recall once of the ancient Greek philosophers claiming that writing would destroy people's intellects. Does anyone recall who that was or where I could find a reference to this?

Victor Mair said,

September 1, 2014 @ 7:51 am

@Joseph

Ancient Indians and Ancient Greeks: Havelock, Parry-Lord, McLuhan, Ong — Orality and Literacy

The monumental shift from oral composition to written literature that took place around the time of Homer, with the perfection of the Greek alphabet, is one of the enduring themes in modern scholarship on the history of writing.

Eric Havelock was deeply involved with these themes in his works. For an introduction, see here:

http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Eric_A._Havelock

and here:

Chinese Characters and the Greek Alphabet (Also available in PDF format.)

Sino-Platonic Papers, 5 (1987).

http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp005_chinese_greek.html

Havelock had a lot more to say about this in works like Preface to Plato and Origins of Western Literacy.

As you might have suspected if you read this far, Havelock provided a key link in the development of the influential ideas of Marshall McLuhan.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_A._Havelock

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_McLuhan

The early Indian authors and thinkers, who were aware of writing from the first millennium BC, firmly rejected it as dulling the powers of the mind. In my Language Log posts (and comments thereto) on the extraordinary success of Indians in spelling bees, I have mentioned the phenomenal memory techniques developed by the ancient Indians, a tradition which still survives.

You'll probably also want to look at the Parry-Lord hypothesis,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oral-formulaic_composition

and studies on orality,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orality

as well as the classic work of Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_J._Ong

Note that Ong's M.A. thesis adviser was Marshall McLuhan, so there's an intellectual genealogy that stretches back through McLuhan to Eric Havelock. The latter's work was considered highly controversial and was scorned by mainstream classicists, but I think that Havelock was penetrating in his insights, prescient in his views, and correct in his analysis. I'm not sure, but I think that the article he published in Sino-Platonic Papers was one of the last things he wrote. I am proud to have dragged Havelock out of semi-retirement at Vassar College and to have commissioned him to write that that perceptive piece on Chinese characters and the Greek alphabet.

Thomas Bartlett said,

September 1, 2014 @ 2:34 pm

Havelock's Sino-Platonic essay interests me very much. He was chair of Harvard's Department of "The Classics" when I majored in Greek literature there. I began learning Greek as a sophomore; my original motive for learning Greek was to read philosophy. With that in mind, I spoke one day with Havelock, who said, "Plato was a fascist", a notion that seemed shockingly iconoclastic to me then. I did read Symposium and Socrates' Apology, but most of my readings were in the diverse introduction to Greek literature that was the standard undergradate curriculum: Homer, Hesiod, lyric poets, half a dozen tragedies, some comedy on the honors translation examination, Thucydides (great stuff!), Herodotus, and a bit of rhetoric.) In senior year I read Aeschylus' drama, Agamemnon, for the thesis. Milman Parry's son, Adam Parry, was my thesis supervisor, a very nice man. It was a very valuable experience. Later, Havelock and Parry went to Yale, and invited me to do graduate study there, but I went to Princeton to start Chinese. My Greek books were stolen from the storage room in the Princeton Graduate School basement, and I haven't kept up reading Greek. Havelock's Sino-Platonic essay makes clear that he's not arguing a "racial" basis for the superiority of Greek literacy. He argues the subject from a technical standpoint at the critical transition from orality to literacy. The early 20th century German classicist, Bruno Snell, wrote "The Discovery of the Mind", which seemed to argue that rationality was unknown anywhere before classical Greece. Havelock resolves this by his distinction between orality, which he hypothesizes is equivalently "rational" universally, and literacy, which is evidently not. Snell does not make this distinction; his book was assigned reading in my undergraduate years and it appeared to me to imply an attitude that might now be called, justifiably or not, "racist". Anyway, my strong reaction against that implication prompted my interest in learning a non-European language. Havelock's argument, that written Japanese can represent science already known, but is not effective for producing new science, is provocative, and apparently has implications for Chinese. Despite all the contemporary focus Middle Eastern affairs, I don't regret having chosen Chinese instead of Arabic.

Daniel Barkalow said,

September 3, 2014 @ 12:45 pm

It is obvious in retrospect that the real effect is that exposure to science and nature in the present makes you less capable in the past. Not only was the experimental group adversely affected by the experiment in the period before it happened, people who will read this study when it comes out in October are saying dumb things now. Fortunately, the effect seems to be exclusively anti-causal, so people should be completely unaffected by this study come November.