Debasing the coinage of rational inquiry: a case study

« previous post | next post »

A little more than a week ago, our mass media warned us about a serious peril. "Scientists warn of Twitter dangers", said CNN on 4/14/2009:

Rapid-fire TV news bulletins or getting updates via social-networking tools such as Twitter could numb our sense of morality and make us indifferent to human suffering, scientists say.

New findings show that the streams of information provided by social networking sites are too fast for the brain's "moral compass" to process and could harm young people's emotional development.

MSNBC asked "Is Twitter Evil?". The Telegraph explained that "Twitter and Facebook could harm moral values, scientists warn". Other headlines from 4/14/2009 include "Twittering, rapid media may confuse morals", "Does texting make U mean?", "Hooked to facebook? Beware", "TV News More Damaging to Empathy Than Twitter", "The social networking, anti-social paradox","Study: Twitter erodes morals", "Twitter makes users immoral, research claims", "Twitter's moral dangers outlined", "Facebook hurting moral values, says study", "Twitter, Facebook Turn Users Into Immoral People", "Twitter could make us immoral", "Twitter can make you immoral, claim scientists", "Facebook and Twitter 'make us bad people'", "Digital Media Confuse the Moral Compass", …

As usual when stuff that people like is shown to be bad for them, the public apparently discounted these dire warnings. According to a poll reported at the Marketing Shift blog, when asked "Do social networks and rapid updates desensitize you to sad news?", 74% said "no", 13% said "maybe", and only 13% said "yes".

In this case, the public skepticism was a good thing, because the news reports were a load of hooey.

The timing of streams of information did indeed cause some public immorality in this case — but the guilty party was not Twitter or Facebook or TV News, but rather the National Academy of Sciences, in whose Proceedings the cited reseach was published. In accord with its usual practice, PNAS released the embargo for journalists a full week before the paper was available for other scientists and the general public to read. As a result, the news media could spread nonsense-pretending-to-be-science (almost) unchallenged for seven of those famous 24-hour news cycles.

And "nonsense" is far too mild a word for the way these stories described the research of Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Andrea McColl, Hanna Damasio and Antonio Damasio, "Neural correlates of admiration and compassion", PNAS, published online April 20, 2009. I haven't seen such a spectacular divergence between evidence and science journalism since the infamous "email and texting lower the IQ twice as much as smoking pot" case of 2005.

Here's what the experimenters actually did, as described in their abstract:

In an fMRI experiment, participants were exposed to narratives based on true stories designed to evoke admiration and compassion in 4 distinct categories: admiration for virtue (AV), admiration for skill (AS), compassion for social/psychological pain (CSP), and compassion for physical pain (CPP). The goal was to test hypotheses about recruitment of homeostatic, somatosensory, and consciousness-related neural systems during the processing of pain-related (compassion) and non-pain-related (admiration) social emotions along 2 dimensions: emotions about other peoples' social/psychological conditions (AV, CSP) and emotions about others' physical conditions (AS, CPP).

The basic findings were nothing very new:

Consistent with theoretical accounts, the experience of all 4 emotions engaged brain regions involved in interoceptive representation and homeostatic regulation, including anterior insula, anterior cingulate, hypothalamus, and mesencephalon.

They did find "a previously undescribed pattern within the posteromedial cortices (the ensemble of precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, and retrosplenial region)" in which "emotions pertaining to social/psychological and physical situations engaged different networks aligned, respectively, with interoceptive and exteroceptive neural systems".

They told each of their 13 subjects (probably USC medical students) 60 stories, written and produced by the experimenters, "supplemented by combinations of audio/video/still images". One kind of story centered on "social pain", a second one involved "bodily injury without social consequences", a third featured "virtuous acts", and a fourth described "virtuosic skill without virtuous implications". You can read some sample stories here.

The subjects actually viewed the narratives in a preparatory session. Then while they were in the scanner, they "viewed short [five-second] reminder versions and were asked to think about the complete narrative that they had been told earlier, to become as emotional as possible, and to report the strength of their emotion via button press".

Note that the goal of the experiment, as its title indicates, was to sort out the "neural correlates of admiration and compassion". The reason for the five-second reminder versions was not to imitate Twitter, Facebook, and TV News, but to deal with the problem of how to fit their subjects' responses to 60 narratives — 12 in each of four categories — into a single fMRI session.

One of the things that they expected to find, on the basis of common sense as well as some prior research, was that "the activity correlated with CPP ["Compassion for Physical Pain"] would peak earlier and extinguish more quickly than the other emotions". To test this hypothesis,

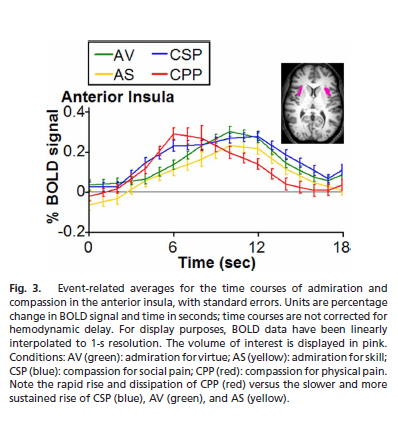

… we used double-gamma curve fitting to compare the ERA time courses of the BOLD effects associated with each of the conditions in the anterior insula (see Fig. 3). Duration was calculated from the width of the curves at half-height. […] CPP peaked more quickly than each of the other emotions and had a shorter duration (see Table S4 for details).

Here's their Figure 3:

[In interpreting such graphs, keep in mind that the hemodynamic impulse response to a single neural event takes 3-4 seconds to reach its peak, and 10-15 seconds to return to baseline.]

And here's their Table S4, slightly expanded:

| Condition | Time to peak (SE) [SD?] | Duration (SE) [SD?] |

| Admiration for Virtue | 9.81 (0.25) [3.12] | 8.79 (0.54) [6.74] |

| Admiration for Skill | 10.60 (0.32) [4.0] | 7.76 (1.01) [12.61] |

| Compassion for Social Pain | 8.73 (0.24) [3.0] | 11.89 (0.96) [11.99] |

| Compassion for Physical Pain | 7.07 (0.46) [5.75] | 7.21 (0.58) [7.24] |

Note that the differences in average time course here are on the order of one to four seconds.

They don't give us any estimates of effect size. So I've calculated the standard deviations, assuming that the standard errors they give were determined on the basis of 13 subjects times 12 narratives per category, for N=156. If this is correct, then the effect sizes for time to peak are moderate to large-ish — the average time-to-peak difference between CSP and CPP was 1.66 seconds, d=0.36; the average difference between AS and CPP was 3.53 seconds, d=0.71). The effect sizes for duration are small to moderate (a mean difference between AS and and CPP of 0.55 seconds, d=0.05, and a mean difference between CSP and CPP of 4.68 seconds, d=0.47).

But wait, how did they test the way that Twitter and Facebook and TV News "numb our sense of morality and make us indifferent to human suffering"? Um, well, they didn't.

OK, so how do these interesting but frankly underwhelming results suggest that "Using Facebook or Twitter may make you a bad person because it ruins your moral compass", as one news story put it? How did another reporter conclude from this research that "the digital torrent of information from networking sites could have long-term damaging effects on the emotional development of young people's brains"?

Well, it all started with the press release by Carl Marziali, "Nobler Instincts Take Time", USC News, 4/14/2009. Here's how he spun the research:

“For some kinds of thought, especially moral decision-making about other people’s social and psychological situations, we need to allow for adequate time and reflection,” said first author Mary Helen Immordino-Yang of the USC Rossier School of Education.

Humans can sort information very quickly and can respond in fractions of seconds to signs of physical pain in others.

Admiration and compassion – two of the social emotions that define humanity – take much longer, Damasio’s group found.

Their study appeared online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Damasio’s study has extraordinary implications for the human perception of events in a digital communication environment,” said USC Annenberg media scholar Manuel Castells, holder of the Wallis Annenberg Chair of Communication Technology and Society at USC. “Lasting compassion in relationship to psychological suffering requires a level of persistent, emotional attention.”

It's tempting to joke that for Annenberg communications professors, "persistent emotional attention" apparently involves a time span of 1.66 seconds, the mean time-to-peak difference between insula activity in compassion for social pain and compassion for physical pain. A more realistic explanation is that Prof. Castells didn't bother to read the paper, or to learn anything at all about the underlying research, but just offered a useful sound bite in ritual response to a leading question from Carl Marziali.

And similarly, I suspect that Marziali pestered Dr. Immordino-Yang until she gave him the quote that he needed to support the preposterous spin that he'd decided to put on this story.

I can't be sure about this, of course — it's also possible that the scientists involved pimped their research to Mr. Marziali in a completely unethical way, and he naively accepted their account.

The next key contributor to the process was the anonymous editor who headlined Science Daily's reprint of Carl Marziali's press release as "Rapid-fire Media May Confuse Your Moral Compass, Study Suggests". Again, I'll bet that no one at Science Daily even glanced at the PNAS paper, even if they were given access to it. In any case, at this point the stage was set for the epic paroxysm of poppycock that inevitably followed.

Everyone involved in this process comes out badly, in my opinion. Carl Marziali, who wrote the USC press release, should go back to selling real estate, or wherever he learned the ethics that he displayed in this case. Antonio Damasio, the senior researcher and last author of the cited study, was at best asleep at the switch — he surely knows that cognitive neuroscience tends to make people tolerant of illogical reasoning, and it's shameful that he doesn't keep a more careful watch on the press releases coming out of his lab. The lead author, a junior researcher, was either naive about the ways of flacks and hacks, or complicit in pimping her study. The Annenberg professor, Manuel Castells, should be ashamed of himself for stepping up on cue to supply a spurious Moral Lesson that had nothing whatever to do with the underlying research. (Please insert an extra 1.66 seconds at this point to allow your appreciation of social pain to develop fully, while reflecting on how Prof. Castells allowed himself to be presented as a pompous fraud.) The National Academy of Science once again abetted the public dissemination of pernicious nonsense by releasing a paper to journalists a week before making it available to anyone else.

And the world's science writers, of course, swallowed the press release and regurgitated their own fermented versions of it: "Twitter can make you mean"; "Scientists from the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California believe heavy users of Twitter and Facebook could become 'indifferent to human suffering'",; "exposure to constant news bulletins … could harm young people's brain development by not giving them enough time to process information about others' emotional pain [and] may also affect the ability to feel admiration for the good deeds of others".

Kudos to Ben Goldacre, whose BS detector went off on cue, and who managed to get an early copy of the paper by some back-channel route ("Experts say new scientific evidence helpfully justifies massive pre-existing moral prejudice", Bad Science, 4/18/2009), and to Chris Matyszczyk at CNET, who was suitably skeptical on the basis of common sense ("Oh, so now Twitter is making us immoral", 4/15/2009). Chris also wins Best Line: "Your brain might, at this point, be scanning the thought that if all the subjects of this research were from Los Angeles, it might be surprising that the scientists found any moral compass at all."

And props to the 74% of respondents in that internet survey who weren't persuaded by this fake-scientific morality play. All the same, though, their skepticism underlines the collateral damage done by such garbage. The media's usual motivation in cases of this type is to give pretend-scientific justification for "pre-existing moral prejudice", as Ben Goldacre observes. That's the hook for readers and viewers. But such stories also debase the coinage of rational inquiry taken as a whole, confirming the common prejudice that it's OK to act on any beliefs that take your fancy, since science is all meretricious bullshit anyhow.

Evie said,

April 22, 2009 @ 10:11 am

Another classic case of 'you can't believe what you read'. I agree, it's sad that these incidents make us, if nothing else, numb to scientific findings. Certainly next time I read a headline involving scientific evidence helpfully justifying massive pre-existing moral prejudice, I'll think twice before jumping to outraged conclusions.

Adrian said,

April 22, 2009 @ 1:24 pm

Lots of us emailed Ben Goldacre about this. The headline itself was enough to set off many, many BS detectors.

Rusty said,

April 22, 2009 @ 2:03 pm

To me, it's just the usual situation of the press doing what they've always done, which is to present news in a way that maximizes newspaper, magazine, etc. sales. It's capitalism at its finest (no, I'm not a communist, even though I work in Berkeley, CA).

I wouldn't be too hard on anyone who was interviewed by the media; until you've been interviewed, you have no idea how amazing their skills are at mangling what you said, taking things completely out of context, leaving out the critically important bits, and so on.

[(myl) My first experience seeing myself quoted as saying things that I never said, or at least never meant, was about 40 years ago — and it was not, alas, the last time. These experiences left me with an interest in the rhetoric of journalistic quotation, and considerable sympathy for those who are misleadingly quoted. For further discussion of these points, see e.g. "Twang scholar on the constraints of journalism", 11/30/2003; "Imaginary debates and stereotypical roles", 5/3/2006; "Ritual questions, ritual answers", 6/25/2005; "Down with journalists", 6/27/2005; "Approximate quotations can undermine readers' trust in the Times", 8/27/2005; "News and entertainment", 9/11/2006; "In president, out president, fake president", 12/5/2008; "Filled pauses and faked audio", 12/28/2008; etc.

I've often suggested that in cases of uncertain attributional abduction, the rule of thumb ought to be to blame the journalist. However, in this case we can fix blame fairly precisely on the person who wrote the press release. And he works for the University of Southern California; so if his text was not approved by the scientists whose work he's paid to publicize, it's because they failed to pay attention to the problem.

It's also certainly true that all the economic incentives — not just those in the news business — tend to promote this kind of coverage (see e.g. "Flacks and hacks and brainscans" for more on this.) The only thing preventing all media from being drowned in a sea of seductive idiocy is the fear of reputational damage. So the best thing that the rest of us can do is to give guilty parties in our own areas as hard a time as possible, whenever the occasion arises. Hence this post. ]

Rubrick said,

April 22, 2009 @ 6:56 pm

"Epic paroxysm of poppycock" is good, but I think "poppycoxysm" would be even better.

Jan Schreuder said,

April 22, 2009 @ 8:05 pm

Again I want thank Mark for his persistent pestering of the peddlers of pernicious poppycock.

Adrian Morgan said,

April 22, 2009 @ 9:41 pm

I found the press release interesting (and linked to it on my blog) not because of the Twitter angle, or the study itself, but because I found the questions raised in the article interesting to think about. It got me thinking. In my link I described it as a "reflection", not a revelation, implying a reminder of what we already know rather than a new discovery. The press release states that the study "raises questions" about broader philosophical issues, not that it provides any answers, and it's the questions that caught my attention.

Here's what I get from it. People talk about food for thought. People also talk about the basic food groups – meat, fruit/veg, dairy, etc. So reading the press release made me wonder what a list of the food groups of the mind might look like, a list of types of thought that people should regularly make a point of thinking in order to maintain a healthy mind. For example, scepticism might be one, and compassion might be another. The extent to which our lifestyles give us more opportunity to express some thoughts rather than others is worth taking some time to reflect on, I think, and for me the press release brought into focus questions that were in the back of my mind in any case. That's why I found it interesting.

The fact that the philosophical digression and the actual study are completely disconnected from each other doesn't change the value of the former in their own right, but I hadn't realised just how disconnected they are. Thanks for drawing attention to the gulf.

nascardaughter said,

April 23, 2009 @ 2:49 am

Thank you for bringing up research ethics in relation to this stuff.

I don't know the details in this case and wouldn't want to pick on these particular researchers, but it seems to me that there is a larger issue than individual cases or researchers — a kind of institutional mindset that the research world has no responsibility when it comes to how research findings are presented to the public.

In many contexts, the expectation that research findings will be presented (accurately!) to the public is pretty much the entire ethical justification for doing research involving human subjects in the first place. I'm not sure that throwing up one's hands over the suckiness of journalism is really living up to one's ethical obligations in those situations. At the very least, universities should not be putting out press releases that misrepresent their researchers' findings, or that obviously invite "sexy" but misleading interpretations.

David Eddyshaw said,

April 23, 2009 @ 6:26 am

Ben Goldacre has it spot-on:

"Journalists have a 1950s B-movie view of science."

Bill Walderman said,

April 23, 2009 @ 8:09 am

When will we see the David Brooks column on this?

Morten Jonsson said,

April 23, 2009 @ 9:32 am

My high school football team was the Poppycocks. The East-Central Poppycocks. The closest they ever came to an epic paroxysm was the time they almost beat Fairway North.

links for 2009-04-23 « Embololalia said,

April 23, 2009 @ 2:05 pm

[…] Language Log » Debasing the coinage of rational inquiry: a case study A little more than a week ago, our mass media warned us about a serious peril. "Scientists warn of Twitter dangers", said CNN on 4/14/2009: (tags: science twitter journalism psychology badscience) […]

Interesting Stuff: Late April 2009 « The Outer Hoard said,

April 23, 2009 @ 7:03 pm

[…] I hadn't realised it was misreported by the authors of the press release, too. See my comments here on why I included this […]

pv said,

April 23, 2009 @ 7:04 pm

The warning alarm should go off as soon as you see the immortal words, "Scientists say…" Why scientists actually tolerate this persistent and deliberate misrepresentation of their work is something I don't really understand. No-one surely, apart from the moral bankrupts and scum of the press and a few corrupt politicians, can see any virtue in promoting the public misunderstanding of science.

Neuroskeptic said,

April 24, 2009 @ 4:15 am

I have a theory that any article about Twitter will, inevitably, be stupid because there is nothing sensible to write about Twitter.

The oh-shit-I-forgot-to-blog blogaround! « Gender Goggles said,

April 25, 2009 @ 1:58 am

[…] And, finally, from Language Log we have "Debasing the coinage of rational inquiry: a case study." […]

Garrett Wollman said,

April 25, 2009 @ 12:07 pm

In today's media world, we should be pleasantly surprised when journalists get any element of fact correct in a situation where falsehood would not subject them to a defamation suit.

manuel castells said,

April 29, 2009 @ 2:16 am

I never said anything about twitters or morality, and I said explicitly I did not see any implications for social space, I just mentioned some hypothetical consequences for violence shown in TV. You can decide who started this crazy story, but it certainly were not the scientists at USC. Manuel Castells

Does Twitter Overload Your Brain? | Photonbelt said,

May 5, 2009 @ 5:26 am

[…] erupted: Neurocritic, Language Log, Bad Science, and others, all posted piecescorrecting the hype. Because of a research embargo, the actual paper was released to journalists a week before release […]

If the internet remaps your brain, your phone remaps your city | Some Random Website said,

May 27, 2009 @ 12:54 pm

[…] 'make us bad people' caught people's attention. With a bit of digging around, the Language Log blog joined the dots between the report and the headlines and found that the actual research had nothing at all to do with social networks or fast-paced […]

When texting kills « Arnold Zwicky’s Blog said,

November 5, 2009 @ 2:51 pm

[…] communications in general) as evil in various ways. A small sampling of postings: here, here, here. (There's also a long series of cartoons on texting and so on, mostly about […]

Carl Marziali said,

November 10, 2009 @ 5:55 pm

No researchers were pestered in the making of this release.

Some facts are missing from this blog post. The much-maligned “world’s science writers” who responded to the release produced responsible stories — for National Public Radio, TIME.com, LiveScience, Fast Company, the Sunday Times of London, and several foreign-language outlets. The alarmist stories cited in the post came mostly from non-science writers, particularly in some British papers and at CNN, which had just canned its science unit. Those stories were followed by a round of reactions from skeptical science writers.

The Facebook half of the story resulted from distorted coverage of another university’s news release, about a presentation of student research. That release came out the same week as ours. Several articles lumped the studies together, or confused the two.

The PNAS paper made this claim: that “the rapidity and parallel processing of attention-requiring information, which hallmark the digital age,” may disrupt the operation of emotions tied to our morality, with potentially negative consequences.

The claim was subject to caveats, noted in the release: the study was small; humans will always have opportunities to experience moral emotions offline; the authors were not concerned about any one media technology, but about possible effects from heavy use of all types of fast-paced media, specifically by adolescents.

The paper did not need to be obtained through some "back channel." We were providing it to any journalist who asked. Very few did.

The writer of the post is generous with insults towards all involved, ironically in the name of deterring "unethical" practices. In an age where personal attacks can remain online indefinitely and where most bloggers try to foster civil exchanges, this post seems over the top.

Panel at Harvard: Evolutionary Biology Looks at Videogames (Who Plays Games and Why) « Dan Scherlis said,

June 3, 2010 @ 10:34 pm

[…] empathy? This much-reported bit of bad science reporting (mentioned during our discussion) was debunked soundly by my favorite blog, Linguistics Log. As computational linguist Mark Liberman insists, "I […]

mcfirefly said,

September 11, 2011 @ 6:33 pm

Why should I need a research study to tell me that it takes time to consider the moral consequences of my actions, when it is known by the conscience of everyone and is the common experience of man? And yet, such is the power of scientists that we seem to believe that it is safe to believe what we actually already know only when a scientific study comes along to validate the obvious.

We should be grateful that people occasionally spend the 6-8 seconds to consider and respond with empathy rather than waiting for the research about the matter to come out and give them permission.