"Ghoti" before Shaw

« previous post | next post »

One of the sturdiest linguistic canards is that George Bernard Shaw facetiously proposed spelling fish as ghoti, with gh pronounced as in laugh, o as in women, and ti as in nation. This respelling, the story goes, was intended by Shaw to highlight the absurdity of English orthography. But ghoti appears nowhere in Shaw's writings, according to devoted Shavians who have thoroughly scoured his works. The earliest attribution of ghoti to Shaw that I've found is from 1946, and the attributor is Mario Pei, not always the most reliable source when it comes to language-related information. By that point, ghoti had been circulating in the popular press for nearly a decade. Previously, the earliest known appearance of ghoti was from a 1937 newspaper article discovered by the redoubtable Fred Shapiro. That still allows for the slight possibility that Shaw was the originator, if unnamed. But now Matthew Gordon of the University of Missouri-Columbia has antedated ghoti — all the way back to 1874. And the 1874 article is quoting a source from 1855, a year before Shaw was born.

As is often the case, the news of this momentous antedating was announced on the American Dialect Society mailing list. Thanks to Chadwyck-Healey's British Periodicals database, Gordon turned up an article from the October 1874 issue of St. James's Magazine by S. R. Townshend Mayer, entitled "Leigh Hunt and Charles Ollier". The article focuses on the relationship of Hunt, a noted writer, and Ollier, his publisher, as reflected in a series of unpublished letters. On p. 406 of the article, an 1855 letter from Ollier to Hunt is quoted:

(Charles Ollier's son William, by the way, was born in 1824, according to an online genealogy, making him 31 at the time the letter was written, so this wasn't simply a child's diversion.)

Mayer's article is unclear about when the letter containing ghoti appeared, so I went searching for online sources on correspondence between Hunt and Ollier. As it happens, librarians at the University of Iowa have recently initiated the Leigh Hunt Digital Collection, putting a large collection of Hunt's correspondence online. There are letters from Ollier in the collection, but not the crucial ghoti letter. I got in touch with Nana Holtsnider, the project manager, and she helpfully located the relevant letter among the copies and transcripts of correspondence collected by the late Hunt scholar David R. Cheney. The ghoti letter is dated December 11, 1855. According to Cheney's citation, the five-page letter was held at the British Museum Department of Manuscripts (Add. MS. 38, lll, fols. 184-186), so it should now be tucked away in the British Library. (Anyone want to go dig it up? Catalogue record is here.)

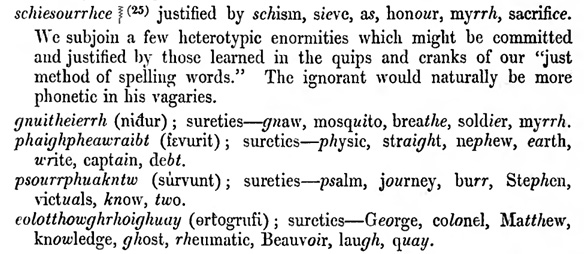

An antedating of more than 80 years is certainly startling, but it actually makes sense that ghoti made its earliest appearance in the mid-nineteenth century, when English orthographic reform was gaining popularity. A decade before Ollier's letter, in 1845, the spelling reformer Alexander J. Ellis published A Plea for Phonotypy and Phonography, which contained some ghoti-esque respellings that are even more elaborate in their absurdity, starting with schiesourrhce for scissors:

Ellis apparently errs in his "amusingly extravagant" spelling of scissors, since the final consonant should be /z/ instead of /s/ (as represented by the –ce in sacrifice). [Update: See D. Wilson's comment below.] But his point is clear, and his examples could very well have inspired the simpler ghoti. Finally, if you're wondering what the squiggly line is following schiesourrhce, the footnote explains that it's a "note of laughter." A proto-emoticon! Ellis was clearly ahead of his time in many ways.

D. Wilson said,

April 24, 2008 @ 1:42 am

Several major US dictionaries, including Century, MW2, and MW3, show a variant pronunciation of "sacrifice" with terminal /z/, apparently preferred more for the verb than for the noun (based on a glance at MW2). Similar variant is shown for "suffice" in MW3 and in MW2 (where there is a note about it). Presumably Ellis is referring to this pronunciation.

Ray Girvan said,

April 24, 2008 @ 3:51 am

This appears to be regularly reinvented. The Times Digital Archive finds this for the Times, Tuesday, Nov 02, 1943: "A Hard Spell For Fish Professor Jones On Sounds And Letters: Dr Daniel Jones, Professor of Phonetics at in University College, London, speaking "Reform of English spelling", astonished his audience at the college last night by suggesting the word "fish" could be spelled "ghoti".

Paul Carter said,

April 24, 2008 @ 4:35 am

Aside from all the merriment (and very welcome antedating), there aren't all that many English words in which WORD-INITIAL "gh" represents [f], nor are there that many where WORD-FINAL "ti" represents esh. So if we attempt to get away from a purely segmental way of thinking about orthography, "fish" makes so much more sense than "ghoti". There are plenty of inconsistencies in how English is spelt, but this fascinating orthography of ours doesn't actually allow for "ghoti" as a respelling of "fish".

GAC said,

April 24, 2008 @ 4:55 am

Very interesting stuff. I had no idea that ghoti was so old.

Also, sort of a side-note: It seems that mister Ellis pronounced scissors as /skɪzərz/ or something similar. I've heard people pronounce it with initial /sk-/, but usually as a joke — was it a common pronunciation in the mid-1800s?

Craig Russell said,

April 24, 2008 @ 6:58 am

In response to the GAC: "Schism" can be pronounced with the "ch" silent. Otherwise, the pun that my college European history professor told us would be impossible, something along the lines of Catholics characterizing mysticism as "starting with mist and ending with schism."

And of course having an unneccessary silent 'ch' would suit Ellis's point.

Benjamin Zimmer said,

April 24, 2008 @ 7:11 am

Ray: I came across that article about Daniel Jones in 2004 and wrote about it on the Usenet newsgroups alt.usage.english and sci.lang. As I suggested in those posts, the Times probably exaggerated the significance of the anecdote in its reporting. I doubt that Jones was making a serious suggestion, and I doubt that the audience was "astonished." Still, the article (and similar coverage that I have since found in The Guardian) could have laid the groundwork for the later ascription of ghoti to Shaw. (Jones and Shaw were probably linked in the public consciousness by 1943 — Jones was said to have been a model for Shaw's Henry Higgins; they served together on the BBC's Advisory Committee on Spoken English; they both took an interest in spelling reform.)

Paul: You're absolutely correct, which is why it strains the imagination that either Jones or Shaw would put it forward as a serious example of the way English orthography works. It's more plausible that Jones (and perhaps also Shaw at some point) was simply recycling an old joke — and now we know just how old that joke was.

outeast said,

April 24, 2008 @ 8:18 am

I'm puzzled by the use of 'myrrh', and what this suggests about Ellis' accent (though it may be more a matter of changes in pronunciation).

A speaker of RP English (in the sense of a person with an 'English accent') would not now prounce the 'r' in either scissors /sɪzəz/ or myrrh /mə:/. Ellis' terminal vowel sound in schiessourrhce derives, apparently, from honour /onə/, so he is evidently using the schwa I would expect; so what is the function of myrrh*?

Did Ellis speak with a rhotic accent, and if so was this normal for an Old Etonian in the mid-19th century? Or, alternatively, is the inclusion of this sound a subtle (or too-clever-by-half) joke exploiting the conceit that a person with a rhotic accent would pronounce the Rs in both scissors and myrrh, but that for a non-rhotic speaker the rrh of myrrh would be silent?

*Apart from in funeral rites, that is…

language hat said,

April 24, 2008 @ 9:31 am

This appears to be regularly reinvented.

You mean "repeated." It is far too recondite to have been reinvented.

Did Ellis speak with a rhotic accent, and if so was this normal for an Old Etonian in the mid-19th century?

Probably. The r was in the process of being lost throughout the 19th century, and presumably Old Etonians would be among the last to follow the new fashion. Hogg and Denison's History of the English Language (p. 92) explains that the first clear evidence of r-loss comes in 1791 (in a disapproving remark about London speech); by 1876 "postvocalic /r/ still exists, but it is rare."

outeast said,

April 24, 2008 @ 11:05 am

Thanks Language Hat!

gnorn said,

April 24, 2008 @ 11:49 am

Hogg and Denison’s History of the English Language (p. 92) explains that the first clear evidence of r-loss comes in 1791 (in a disapproving remark about London speech); by 1876 “postvocalic /r/ still exists, but it is rare.”

According to Wikipedia: "The earliest traces of a loss of /r/ in English are found in the environment before /s/ in spellings from the mid-15th century: the Oxford English Dictionary reports bace for earlier barse (today "bass", the fish) in 1440 and passel for parcel in 1468. In the 1630s, the word juggernaut is first attested, which represents the Hindi word jagannāth, meaning "lord of the universe". The English spelling uses the digraph er to represent a Hindi sound close to the English schwa. Loss of coda /r/ apparently became widespread in southern England during the 18th century; John Walker uses the spelling ar to indicate the broad A of aunt in his 1775 dictionary and reports that card is pronounced "caad" in 1791 (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006: 47).".

Andy Hollandbeck said,

April 24, 2008 @ 12:05 pm

It seems that it has been quite a while since we heard from Language Log on English spelling reform, and especially spelling reform societies like the Spelling Society, the American Philological Association, and of course the ongoing "guud werk" of the American Literacy Council.

And I'm sure professional linguists have a lot of opinions about artificially imposing phonetic spelling rules on an entire language…

John Cowan said,

April 24, 2008 @ 3:32 pm

Early loss of /r/ is probably a separate phonological process from the general loss. It has affected American English profoundly even in the majority rhotic dialects, giving us such doublets as parcel/passel (mentioned by gnorn above), girl/gal, burst/bust, curse/cuss, arse/ass, and indirectly saucy/sassy (which latter is a derhoticized version of *sarsy). We no longer have hoss or skasely, which were still in use in the 19th century, though.

Parsnip also belongs here; it's a hypercorrection of ME pasnepe, presumably because people thought an /r/ had been lost.

Kate Gladstone said,

April 24, 2008 @ 4:03 pm

Those in search of strange "phonetic" spellings may like to puzzle themselves and others with one of mine:

GOLOBCH – meant for "jerk"

G as in MARGARINE

OLO as in COLONEL

CH as in CHORUS

vanya said,

April 24, 2008 @ 4:19 pm

Hoss is still found as a jokey or self-consciously "rural" term. I even knew some kids in college who used it as a term of address – "Hey, hoss!" – but I can't remember how that got started.

What struck me from that snippet is that the "ph" in nephew apparently used to be voiced since Ellis uses that for the "v" sound in "favorite." I suppose if it derives from French neveu it makes sense that the middle consonant was once voiced, but it sounds very odd to me. Are there any current English dialects where people say "nevyu"?

mollymooly said,

April 24, 2008 @ 5:15 pm

@Vanya: v in nephew is still common, though old-fashioned, in Britain. Here's John Wells:

Thus in nephew the /f/ form, preferred by 79% of all respondents, proves to be the choice of a mere 51% of those respondents born before 1923, but of as many as 92% of those born since 1962. There is a clear trend line, showing that the /v/ form (which happens to be the one I prefer myself) is due to disappear entirely before very long.

Ray Girvan said,

April 24, 2008 @ 5:16 pm

John Cowan > Early loss of /r/ is probably a separate phonological process from the general loss.

I'm also very doubtful of the Wikipedia version, which seems to oversimplify. How can we know that "juggernaut" is an attempt of accurate phonetic representation of "jagannāth"? English has been very prone to incorporating foreign words with adaptation, often humorous, toward local flavour and idiom (compare "Houssein Hassan" becoming "Hobson-Jobson", and many more forgotten Anglo-Indian borrowings such as "kewānch" becoming "Cow-Itch").

How prescriptive / classist / London-centric were the lexicographers reporting loss of coda /r/ from southern England, it tending to be a southern rural English characteristic? And so on.

dr pepper said,

April 24, 2008 @ 7:20 pm

regarding ph=v, one of my personal language peeves is "Stephen". I think people with that name ought change it to either "Steven" of "Stefen" so we don't have to guess.

Otoh, i happen to prefer the v pronunciation for ph in "phantom", although that's pretty rare.

As for "ghoti", i think it has a fundamental flaw. The f sound in "laugh" isn't from the gh, it's from the u, as in u=v=f. See "leftenant".

language hat said,

April 24, 2008 @ 8:23 pm

regarding ph=v, one of my personal language peeves is “Stephen”. I think people with that name ought change it to either “Steven” of “Stefen” so we don’t have to guess.

I don't think I'll take you up on that. Anyway, no guessing needed: It's pronounced with /v/. At least, I've never met a Stephen who pronounced it any other way.

vic said,

April 24, 2008 @ 8:31 pm

First time I heard of "ghoti" was in 1989 from a sysadmin at the MIT AI Lab. One of their mail servers was tagged "ghoti" and this was ascribed to an AI joke (something about machine-generated orthography). This was only a few months before I heard the Shaw attribution from someone else. I have also seen several quips alternately ascribed to Shaw and Winston Churchill–an odd connection, unless one considers that they are the two Brits whom most American intellectuals of mid-XXth century would consider mischievously witty. So it might be easy, thinking of one, to refer to the other–which is not to say that either one was behind the origin of any of these one-liners.

Stephen said,

April 24, 2008 @ 10:14 pm

I agree with language hat. It's pronounced with /v/.

Mike said,

April 24, 2008 @ 10:54 pm

Was anyone else thrown off by the use of "mention" and "attention" as examples of when ti represents sh? The ti sound in those sounds closer to the ch in wrench than the sh in fish. (Also closer to the tch in wretch, to use an example without an 'n' in it. Either way, more tongue on the roof of the mouth, more of a burst of air than a steady flow. Anyone good with phonetics around here?)

"Nation" is a much better example. There's no way fish was once pronounced as fitch or finch, is there?

Benjamin Zimmer said,

April 24, 2008 @ 11:04 pm

Mike: the ADS-L thread on Matthew Gordon's discovery has some further discussion on the pronunciation of "ti" in "mention"/"attention".

Luke G. said,

April 25, 2008 @ 9:27 am

Rock on Matt Gordon! I took a class with him last year on the History of the English Language.

Ben said,

April 25, 2008 @ 5:42 pm

Here's a bit I always liked from Finnegans Wake:

"Pure chingchong idiotism with any way words all in one soluble. Gee each owe tea eye smells fish. That's U. "

There's some clever stuff in here I actually get, as well as other clever stuff I'm missing. I'll point out my favorite part, which is that the 'U' is a pun on the Mandarin word for fish, 'yú,' which is in keeping with the mock-astonishment at the preponderance of monosyllabic words in Chinese that is, I think, what this passage is about.

language hat said,

April 26, 2008 @ 10:06 am

Thanks for that, Ben!

john riemann soong said,

April 26, 2008 @ 7:29 pm

"The ti sound in those sounds closer to the ch in wrench than the sh in fish."

I almost would say it almost resembles a Mandarin consonant, since the /t/ isn't aspirated and the fricative part of the affricate starts to approach /ʂ/ (but this is my impression as a half-native speaker of English; my native language is an English-based creole).

john riemann soong said,

April 26, 2008 @ 7:34 pm

"I’ll point out my favorite part, which is that the ‘U’ is a pun on the Mandarin word for fish, ‘yú,’ which is in keeping with the mock-astonishment at the preponderance of monosyllabic words in Chinese that is, I think, what this passage is about."

It's not a perfect pun, since /y/ != /ju/ ;-), but didn't /y/ merge into /ju/ in English as well? Though I'm not sure if the passage had that in mind either.

David Marjanović said,

April 27, 2008 @ 6:15 pm

…and the English orthography follows its rules over 85 % of the time! Woohoo!

It goes without saying that the most general Klingon word for fish-like creatures is ghotI' ([ˈʁotʰɪʔ] — though the sources I've seen contradict each other on whether H and gh are supposed to be velar or uvular).

Really? Compare German Zwerg, Schacht with dwarf, shaft (the latter only in the meaning "deep vertical hole in the ground") — I get the impression these two were respelled while laugh was not. For au being pronounced /ɑ/, see aunt.

I know a Stephan by e-mail who is a native speaker of American English. Perhaps he pronounces himself with /f/.

Judging from the response I got on the Pinyin News blog to this very question, it seems that what most native speakers consider their native phoneme closest to [y] is /ju/ (not /i/ as it is for perhaps most other languages that lack [y]).

John Cowan said,

May 2, 2008 @ 1:22 pm

/ju/ for /y/ is actually quite natural; it splits the front rounded vowel into separate tokens of frontness and roundedness, and has been consistently used in English to represent /y/ in French borrowings (native /y/ had gone to /i/ and then /ai/ when long, as in mys > mice). The name of the letter U exhibits this clearly: the names of letters have no recognized orthography in English, and so are particularly pure examples of sound-change at work, being passed solely through oral tradition. English has since lost the /j/ after liquids, as in "rude", and in some dialects after dentals also ("duke" may be /duk/ or /djuk/).

Some languages, though, render all foreign /y/ as /u/, as in Greek tourkos < Turkish türk, which then passed into most European languages that don't have their own front rounded vowels (French uses turc, front rounded; Hungarian uses török, why I don't know; German is apparently inconsistent, though, with Turkvölker vs. Türkei).

Stephen said,

May 2, 2008 @ 2:34 pm

From what I've learned being Irish and named Stephen with a "ph" is…

That the "ph" was the catholics version who were separating themselves from the Protestant version Steven with a "v'. Typical IRISH!!

Just what I've been told…..

Ollock said,

May 2, 2008 @ 11:10 pm

I've noticed among my classmates that Mandarin /y/ and /ɥ/ often end up becoming [ju]. But I think that's mostly a spelling pronunciation, since it usually occurs when the phoneme in question is spelled in pinyin. When it's spelled or , it's often merged with [u] (or [w] for the glide), using the somewhat fronted [u] I hear in a lot of English dialects — which is funny to me as it seems almost like a sort of compromise between [u] and [y].

Steve Bett said,

August 24, 2008 @ 3:18 am

The earliest usage of the ghoti story by G.B. Shaw seems to be 1940.

It was included on post cards he sent out that year. This is probably where Mario Pei got the story and explains why he attributed it to Shaw.

I don't think this means that the story originated with Shaw but it certainly shows that he was involved in spreading it.

Reported on the discussion sponsored by the spelling society by David Everingham who received such a correspondence from Shaw in 1940.. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/ssslist

Shaw did read Alexander Ellis' Plea for Reform but while it contained many plausible spellings for words, e.g. scissors, it did not specifically mention GHOTI. Any other ideas on where he might have picked it up?

Doug Harris said,

November 6, 2009 @ 7:02 am

Guys, I am astounded (and greatly encouraged) by the analytical lengths you have all gone to in uncovering the ghoti truth. I have witnessed bait, hook, line and sinker all on one page to finally catch the beast!

I note the name of Fred Shapiro somewhere near the beginning and was reminded that although I don't know Fred personally, he has spent time I believe trying to uncover the origins of the word 'limerick' in relation to the sometime nonsense verse of a particular rhythmic lilt. Along with Stephen Goranson and Arthur Deex in the US, Greg Gigol in Poland and myself plus Bob Turvey here in the UK (just trying to give everyone a little credit here!) we have antedated its use in print from the OED's 1898 claim to much earlier (possibly as early as 1880 in the National Police Gazette) although I won't go into details here as it is a complex and less than concrete tale just yet.

As an amateur scholar of the history of the humble people's poetry that the limerick is, I find myself lacking in access to research resources and wondered if you might like to misappropriate some of your obvious talents and enthusiasms on this matter? An analysis of the word from language experts would be good too. If you can uncover anything at all, I would be very grateful for a quick email to me at – stride.environmental@virgin.net here in England.

There once was a verse that was slick,

Its rhythm gave folk quite a kick.

But its origin's dark

Will you join in this lark

And unearth me the first limerick?

Best wishes,

Doug

toast said,

July 22, 2010 @ 2:14 am

The only problem I see is that in the old example showed, it says the "ti" is as mention or attention. that TI is more of a CH instead of a SH. It's not pronounced men-shun, rather, men-chun (if you say it out loud it's much easier to understand the difference). That would render the word as fitch, or fich if you're picky about spelling… Which is clearly not Fish at all.