Frances Brooke, destroyer of English (not literally)

« previous post | next post »

I don't have much to say about the latest tempest in a teapot over the non-literal use of "literally." It started, as such things often do these days, on Reddit, where a participant in the /r/funny subreddit posted an imgur image showing Google's dictionary entry for "literally" that pops up when you search on the word. The second definition reads, "Used for emphasis or to express strong feeling while not being literally true." That was enough for the redditor to declare, "We did it guys, we finally killed English." As the news pinged around the blogosphere, we got such fire-breathing headlines as "Society Crumbles as Google Admits 'Literally' Now Means 'Figuratively'," "Google Sides With Traitors To The English Language Over Dictionary Definition Of 'Literally'," "I Could Literally Die Right Now," and "It’s Official: The Internet Has Broken the English Language."

I don't have much to say about the latest tempest in a teapot over the non-literal use of "literally." It started, as such things often do these days, on Reddit, where a participant in the /r/funny subreddit posted an imgur image showing Google's dictionary entry for "literally" that pops up when you search on the word. The second definition reads, "Used for emphasis or to express strong feeling while not being literally true." That was enough for the redditor to declare, "We did it guys, we finally killed English." As the news pinged around the blogosphere, we got such fire-breathing headlines as "Society Crumbles as Google Admits 'Literally' Now Means 'Figuratively'," "Google Sides With Traitors To The English Language Over Dictionary Definition Of 'Literally'," "I Could Literally Die Right Now," and "It’s Official: The Internet Has Broken the English Language."

The outrage was further heightened by the realization that (gasp!) pretty much every major dictionary from the OED on down now recognizes this sense of the word. So now we get vitriol directed toward the OED's lexicographers, who revised the entry for "literally" back in September 2011, coming from such sources as The Times, The Daily Mail, The Guardian, and The Telegraph. [Update: As Fiona McPherson points out on the OxfordWords blog, the usage was actually noted in the "literally" entry when it was first published in 1903. The 2011 revision reorganized the entry and expanded the historical record.]

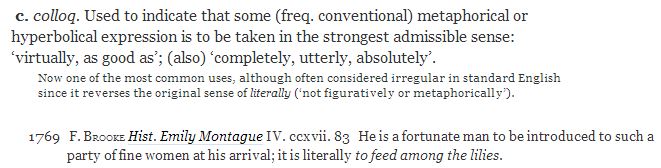

I've previously shared my thoughts on "literally" here on Language Log in a 2005 post discussing a piece on Slate by the OED's Jesse Sheidlower, as well as in a Word Routes column in 2008 ("Really! Truly! Literally!"). If I were pressed to find a silver lining in the latest round of hand-wringing, it would be this: many people are now learning about Frances Brooke, the novelist who is responsible for the earliest OED citation for the hyperbolic sense of "literally," from 1769. I first dug up the citation for the 2005 Language Log post, and it eventually worked its way into the OED's 2011 revision:

(You can read Brooke's History of Emily Montague, an epistolary novel, online here. As Wikipedia informs us, it holds the distinction of being the first novel written in Canada — she lived in Quebec from 1763 to 1768 before returning to England.)

The British press has duly noted that the maligned use of "literally" has been lingering since Brooke's time, but that hasn't stemmed the outrage: it's still wrong, they all say, even if it's been in continuous use for two and a half centuries. But it's a little inconvenient for the peevers, who would much rather blame Google or "the Internet" for the destruction of English. It doesn't make for as good a story to hold an 18th-century novelist responsible for "breaking the English language." Somehow, we've managed to soldier on since the linguistic horror perpetrated by the dastardly Mrs. Brooke.

Matt Williams said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:21 pm

The problem I have with Google's definition is not that they mention the hyperbolic usage but that in defining 'literally' they use the phrase 'not literally'. It's one thing to use a word in its own definition but quite another to use it in a negative sense.

Haamu said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:33 pm

One thing I don't see discussed in all the peeving and meta-peeving about literally is the idea that this word seems to have evolved along a second axis.

Axis #1 is the standard literal-figurative dimension that everyone complains about.

Axis #2 I might call definitional-ontological.

When I look at the earliest OED citations, they seem to be very concerned about the interpretation of texts and utterances. At some point, which looks to me like it might have been in the late 17th or early 18th century, we imbued literally with the power not merely to guide exegesis, but to make ontological claims about what actually exists or happened.

The "definitional" sense of literally might be taken as "exactly as written" or similar wording. The "actually true" sense seems to come later. The former sense seems more consistent with the word's etymology.

My own reply to those who peeve about this is to suggest that if they were using literally literally, they wouldn't use it to mean "actually."

Mar Rojo said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:36 pm

Would the peevers have a problem with "We waited for an eternity for Jon"?

Gene Callahan said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:37 pm

"It's one thing to use a word in its own definition but quite another to use it in a negative sense."

Um, Matt, they are using DEFINITION 1 to help clarify definition two. Perfectly sensible.

Mar Rojo said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:52 pm

You still feel this way, Ben?

Ben Zimmer said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:56 pm

Do I still feel which way?

Wilson Gray said,

August 15, 2013 @ 1:58 pm

Mar Rojo asks:

Would the peevers have a problem with

"We waited for an eternity for Jon"

?

"We waited for Jon for an eternity."

Vance Maverick said,

August 15, 2013 @ 2:40 pm

The Canadian connection is telling. The corruption of the King's English by the colonies goes back 250 years! (And to think that it took only a five-year sojourn to lead her astray.)

Steve said,

August 15, 2013 @ 2:49 pm

Shiedlower's Slate article helped me sort out my thoughts on one piece of this: while I realized fairly early on that peeving against the nonliteral use of literally is futile and wrong-headed, there are certain uses of it that I can't stop myself from cringing at: I.e., when I heard a news anchor report that "hordes of people are literally flinging their babies at the Pope." (For what it's worth, I think replacing "literally" with "really" would make for an even more awkward-sounding sentence "hordes of people are really flinging their babies at the Pope" would mean something a bit different to me, but it would certainly not be an improvement.)

I think the key is this: when literally (and, in some cases, "really") is used as a general intensifier for a metaphor that is overwrought, inapt, hyperbolic, stilted, or otherwise ill-chosen, "literally" has the effect of highlighting the awkwardness of the metaphor. But the fault lies with the poorness of the metaphor, and fixating on the use of "literally" is a mistake, as tempting of a target as the use might be for casual peevery ("hordes of people are flinging their babies at the Pope," would still be a pretty darn silly thing to say, I think).

Theophylact said,

August 15, 2013 @ 3:20 pm

The problem here is that people are mistaking a logical impossibility (P = ~P) for a linguistic one.

I could/couldn't care less.

Toma said,

August 15, 2013 @ 3:33 pm

If the OED revised the definition in 2011, we could say it took Reddit forever to realize it.

Daniel said,

August 15, 2013 @ 3:40 pm

The way the OED and other dictionaries currently carve up the semantic space of sentence-adverbial "literally" seems to me to prioritize a less important distinction over a more important one. Consider the following examples, thinking about what would change if we omit "literally" :

(1) "He had the singular fate of dying literally of hunger." (In context, there is no ambiguity about whether he actually died, and omission of "literally" would merely yield a less emphatic utterance.)

(2) "They're literally throwing money at these programs." (In context, there is no ambiguity about whether actual banknotes were thrown, and omission of "literally" would merely yield a less emphatic utterance.)

(3) "A man is literally torn into pieces." (In context, the omission of "literally" might lead the reader to mistakenly believe that "torn to pieces" is merely used as a figure of speech – e.g. for "verbally abused").

The OED currently treats (1) and (3) together, on the grounds that these sentences are both asserted to be non-metaphorically true; since (2) is asserted to be true only metaphorically, the OED added a separate sub-heading for this usage, treating it as "colloquial." But wouldn't it make more sense to group (1) and (2) together and to regard (3) as the outlier? Adding emphasis to a metaphorical expression isn't so different from adding emphasis to a non-metaphorical expression, but adding emphasis in either case is very different from disambiguating between metaphorical and non-metaphorical interpretations.

[I might be saying the same thing as Hammu here, although I have to admit that I wasn't entirely sure of his meaning at first and am still not sure whether we are trying to say the same thing.]

Michael Jurkovic said,

August 15, 2013 @ 4:42 pm

Here's my only peeve with this word and issue:

It's literally akin to valley girls shrieking "like." Like, literally, life has, like, become so literal it's like literally impossible to distinguish between the like literally vacuous language and the literally important language. If my literally cringe worthy comment hasn't literally emphasized my point, all wanted to say was that this problem will literally never be over. LITERALLY. (facepalm)

J.W. Brewer said,

August 15, 2013 @ 4:54 pm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blame_Canada

Mar Rojo said,

August 15, 2013 @ 6:51 pm

Like this, Ben:

Used effectively, hyperbole should work perfectly well on its own, without needing to add an intensifier like literally. At best it's redundant, and at worst it's an annoying distraction that is sure to raise the hackles of Grumpy Grammar Gus.

Suburbanbanshee said,

August 15, 2013 @ 7:52 pm

Re: flinging babies, the sentence would work fine if you said, "And people _really_ were _flinging babies_ at the Pope!" or "And people were just _flinging_ babies at the Pope!"

Bloix said,

August 15, 2013 @ 7:53 pm

There's a phenomenon that perhaps has a name whereby a word is used hyperbolically for comic or intensifying effect, and over time the hyperbolic meaning takes over the literal meaning and a new word is needed for the literal meaning.

Uriel Harvey said,

August 15, 2013 @ 7:57 pm

I don't have a direct citation for this, but Etymonline claims that the figurative sense of "literally" was used by Dryden and Pope, which would predate the OED's earliest cited use and locate the mutation squarely in the language's motherland.

Ray Girvan said,

August 15, 2013 @ 8:11 pm

@Ben Zimmer: "it's still wrong, they all say"

It must be literally scourges and thorns in their sides to hear it.

–Francis Webber, 1737.

Rod Johnson said,

August 15, 2013 @ 9:28 pm

This post has now shown up at Metafilter, where, unusually, they've missed the point.

Chris Potts said,

August 15, 2013 @ 10:03 pm

@Matt Williams, @Gene Callahan – I was really struck by the token of not literally in the definition of literally. I assumed that it would be rare (because it would embarrass dictionary makers) but attested (because of words like sanction, cleave, peel). So I did some regex searches over the Wiktionary XML and OPTED. I came up empty. Even literally doesn't literally show the pattern, though it acknowledges the ambiguity. The closest match I found was adjectival incorporate to mean 'not incorporated'.

Dominik Lukes (@techczech) said,

August 16, 2013 @ 12:54 am

Funny, on this blog, I would have expected the criticism of Google to be that they got the order of the definitions wrong: http://metaphorhacker.net/2011/02/literally-triumph-of-pet-peeve-over-matter/.

But I think from the vitriol of some of the commenters on io9 and elsewhere that a much more interesting phenomenon is presenting itself for us to study. Namely, what is the source/nature of the deep-seated hatred of language variation as well as this complete inability to see various meanings of words as possible combined with the ease with which such polysemy is navigated in real usage.

exackerly said,

August 16, 2013 @ 1:47 am

I actually posted a comment in that thread on reddit, making the usual points — languages change, dictionaries are descriptive not presecriptive, and anyway "literally" has been used in both senses for centuries. Net karma: 5 points, meaning more people agreed with me than disagreed, but not by much.

Daniel said,

August 16, 2013 @ 4:47 am

@Dominik Lukes:

Thanks for posting the link. I suspected that somebody would already have done a more thorough analysis, but finding it online would literally have been like searching for a needle in a haystack.

greatfirstsentences said,

August 16, 2013 @ 7:52 am

Strange people should get so upset over a word having two opposing meanings. Ever thought about the word 'fast', which means both to move quickly and to be fixed to one spot? Same origin, and very old.

That's language. We can cope with it. Breathe with me…

Corey B said,

August 16, 2013 @ 8:49 am

Without hyperbole, I can say that this is literally the worst thing that has ever happened in the history of a million universes. And that's a fact.

On a less sarcastically humorous note, what is the typical peever's prescription on using "literally" in a simile? (i.e. "Eating this steak was literally like eating dirt.") It seems that "literally" could TECHNICALLY be used correctly in this case, even for the most autistic of linguistic literalists.

It's a philosophical question worthy of Kant or Wittgenstein… can anything ever truly be "literally" "like" anything else? ;)

Dan Hemmens said,

August 16, 2013 @ 9:45 am

I might almost go further. As you point out (1) is unambiguously describing physical death, while (2) is unambiguously describing metaphorical flinging and in both cases "literally" merely intensifies the sentiment. But I would argue that (3) is no less ambiguous for including "literally" (and it is, I think, this loss of disambiguating power – which I am not sure the word ever *really* had – which peevers are complaining about). "Literally torn apart" could be "physically torn apart" or "emotionally torn apart", and the use of the word "literally" doesn't actually disambiguate that.

Alfonso said,

August 16, 2013 @ 9:57 am

This whole thing REALLY gets on my nerves. (See what I did there?)

Daniel said,

August 16, 2013 @ 11:07 am

@Dan Hemmens:

I'm not sure I would go that far. Are you suggesting that sentence-adverbial "literally" is only ever used as an intensifier, never to disambiguate between literal and figurative/metaphorical meanings or words, phrases or sentences?

Mar Rojo said,

August 16, 2013 @ 12:08 pm

Bloix said,

August 15, 2013 @ 7:53 pm

"There's a phenomenon that perhaps has a name whereby a word is used hyperbolically for comic or intensifying effect, and over time the hyperbolic meaning takes over the literal meaning and a new word is needed for the literal meaning."

Semantic bleaching?

Peeving Literally and Figuratively and Every Which Way said,

August 18, 2013 @ 3:31 pm

Some like this use of the word, and some don't.

So that's where we are at.

Matt McIrvin said,

August 19, 2013 @ 8:16 am

I think it just comes from the use of "good grammar" as a marker of high social status or good education. When people profess to be deeply offended or hurt by "mistakes" that the majority of people (or less-educated people, or stigmatized minorities, or kids-these-days) are making, they are placing themselves above the crowd.

Sam C said,

August 20, 2013 @ 9:59 am

Now there's a new sign of the language apocalypse to grab hold of – I was talking with a girl last month who told me she was "technically fourteen." When I asked her what she meant, she explained that her fourteenth birthday was in two months.

I split my side laughing and wondering how long until "technically" doesn't hold its literal meaning anymore, if this thirteen-year-old girl is a portent of things to come. Can't wait to see peevers clutch their pearls over that one.

Mark Shulgasser said,

August 22, 2013 @ 9:58 pm

One isn't "deeply offended or hurt by 'mistakes' that the majority of people (or less-educated people, or stigmatized minorities, or kids-these-days) are making"; one is simply aware (perhaps gratefully) that one is . . . more educated. The L word is often carelessly used for rhetorical emphasis because its meaning seems simple whereas it's actually full of philosophical pitfalls. It need not appear in a person's vocabulary more often than its opposite, "figuratively." I would use it only to indicate that a phrase which seems figurative is not. Other uses are gushy, inane and simply convey that the speaker is foolish. I don't object to the use, because it's good to know that someone is foolish, if they are.

DameAlys said,

August 26, 2014 @ 2:03 pm

I'm just glad Canada's getting blamed for something, for once, instead of the U.S.!