"Book from the Ground"

« previous post | next post »

Earlier this year, I wrote about "The unpredictability of Chinese character formation and pronunciation". In that post, I had a long section on the artist Xu Bing's "Book from the Sky".

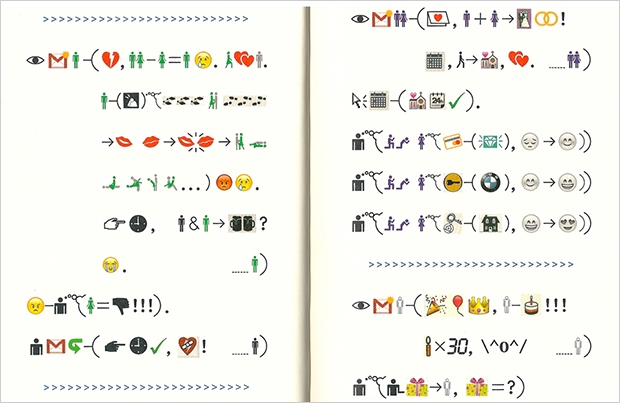

Now the artist has created a parallel "Book from the Ground". Here's what it looks like:

This is supposedly the Everyman Tale in icons. Forgive me, but even after studying up on Xu Bing's principles employed in creating his "Book from the Ground", I must confess that I cannot read off what he has written in English, which is theoretically supposed to be possible. I wonder how many Language Log readers are capable of doing so. Since Xu Bing has been engaged in this project since 2003, we may politely say that it is a "work in progress".

All of Xu Bing's experimental scripts probe the boundaries of the established conventions of writing. For example, in Square Word Calligraphy Xu arranged the letters of English words into quadrilateral shapes like Chinese characters. David B. Kelley went a step further and adapted Xu Bing's system of Square Word Calligraphy by replacing the Roman letters of English words with Chinese character components that resemble them.

Kelley's Square Word Calligraphy even made it into Omniglot, so somebody seems to have taken it (half) seriously.

There are many other artists in China who are exploring ways to transform and revitalize the Sinographic writing system, but most of them are whimsical or satirical, with few making any real pretensions to replacing or modifying the existing script. I'm quite certain that Xu Bing's "Book from the Ground" will never be refined to the point that it can replace existing scripts either. Consequently, when it comes to reforming the Chinese writing system, which has been a preoccupation of countless linguists, artists, and activists during the past century and more, for practical purposes reformers are forced to fall back on the two main approaches of simplification and phoneticization.

[A tip of the hat to Anne Henochowicz]

Jason said,

December 5, 2012 @ 11:32 am

Blissymbolics, anyone?

Jeroen Mostert said,

December 5, 2012 @ 12:13 pm

Bob saw a mail from Charlie that Carol broke his heart. She cheated on him with another guy that she met at a mountain (? I don't know what that pictogram means). They slept together and now Charlie's really upset and he'd like to meet Bob for drinks to discuss his heartbreak. Bob thinks Carol's a bitch for hurting Charlie. He replies to make an appointment for drinks to comfort his friend. That's page 1.

On page 2 he's got a wedding invitation, and he accepts. The next bit is trickier to me — he's thinking about how women will be increasingly more happy with you if you offer them more lavish gifts? Is he comparing or is it a sequential train of thought?

Finally he's got a birthday invitation from Dave, who's turning 30. Bob's got no idea what to get Dave for a present yet.

I must confess it took a while for most of this to "click". My initial reaction was that I couldn't read it and it seemed too unstructured to confidently decode, but maybe this is just inertia. One thing that does rest slightly uneasy with me is how I have little opportunity for confirming my interpretation of the story is correct — the language has no previously agreed-on semantics since I didn't study it. Overall, though, I think it's pretty impressive.

Andy Averill said,

December 5, 2012 @ 12:52 pm

Page 2, Charlie thinks — I'll bet he had to promise her a diamond ring (bought on credit), a BMW and a house to get her to marry him.

Andy Averill said,

December 5, 2012 @ 12:55 pm

If you follow Victor's link, it appears that all the drawings have English translations, it's mostly pretty banal stuff. Except for the part about "he went to the park and shot an elephant"…

Jeroen Mostert said,

December 5, 2012 @ 1:19 pm

@Andy: it seems to me that a language like this has inherent problems expressing complications or nuances unless you transition to a "full" language that's not so readily understandable. I see parallels with Basic English, with the same problems. Of course, the unique "edge" is that things that readily lend themselves to graphical depictions (like "shooting an elephant") are trivial to convey, you just display them.

Depicting things like "the smell of the coffee reminded him of the trip to Saudi-Arabia he had in his student years, where just this blend had been served to him by a girl he still had wistful memories about" would be seriously involved, and you could legitimately wonder how accurate any translation could be.

Ray Dillinger said,

December 5, 2012 @ 2:17 pm

If Book From The Sky was a nonsense game, this is a sense game.

Here is a question; how does the idea of writing originate? The rest of this is my (somewhat speculative) answer to that question.

It originates when someone thinks, hey, I can draw this thought. I can make a little picture story, and then whoever looks at the pictures will know the story.

So that person painstakingly draws something like a 'Henry' comic strip (classic wordless comics that tell little stories) and successfully (though with great effort) communicates stories about identifiable people and their interactions with concrete things.

Icons are what you get when you attempt to express abstractions. You generalize the process, using the same picture each time you need to communicate the same meaning. The "story" context is abstracted away, and a lot of images of concrete things are used to communicate culturally specific abstractions — like, for example, the 'heart' icon above to mean 'love' or the 'rings/bridal gown' to indicate 'marriage/getting married'.

My point is that icons, as opposed to pictures, stand for things not pictured. They stand for actions, for ideas, for abstractions, for attitudes, etc. Now you can tell stories about abstract things, but your audience has to have the same cultural knowledge as you to associate the icons you use with the same ideas you're using them for. This is, IMO, the last stage that isn't really "writing" as we understand it. Cultural knowledge is certainly required, and language as such starts to be present in that icons written in a sequence will tend to be written in the same order a speaker would use those ideas — so the basic word order of, say, SOV or SVO languages becomes apparent.

Also, as soon as an icon is associated with a particular word of language, people will naturally start using it phonetically in rebus writing, so you start seeing indications about the relationships between pronunciations of words.

Icons get worn down, decorated, etc — the cultural associations they're attached to changes while the icon changes gradually in unrelated ways, and always they get simplified for drawing faster. Eventually you have a sign for each item of discourse, and the signs may become less obviously related to the items. At some point the system gets formalized, with a sign for each *word*, and you have a writing system as we understand it.

Xu Bing is sort of exploring the relationship between signs and meaning. Just as Book From The Sky was signs divorced from sense, this is more about expressing sense with a system of signs so primitive it requires only the cultural and linguistic knowledge (rather than prior knowledge of a particular writing system) of English-speakers to interpret. This is the most expressive you can be without using an actual writing system as such, and, I think, probably analogous to the historical roots of all written language. This is right at the point of writing's emergence, where signs have grown standard forms and semi-formalized interpretations, but can still be "read" by the intended audience without using literacy in a writing system as such.

Ray

Bruce Rusk said,

December 5, 2012 @ 4:12 pm

A couple of years ago, in a course I taught on East Asian writing systems, I assigned part of this document to the students to render into English, then we did a joint "translation" in class. In many places they read the text quite differently from one another, though in other places the readings generally coincided.

One of the issues that came out of the discussion was how certainly languages require certain features, such as tense, that can be elided in others: the students had to decide whether to put the story into the past or present tense, and either worked. This allowed those who don't know Chinese to experience some of the complication of the translation process.

I found this useful as a teaching device, however problematic Xu Bing's claims about its universality. It is reminiscent of early modern European attempts to create universal languages, often based on a flawed but far from defunct understanding of how Han characters work.

Ray Dillinger said,

December 5, 2012 @ 11:35 pm

Did Xu Bing make any claims about universality?

As I recall he said it could be rendered as English. And he deliberately uses a lot of culturally-specific icons that will suit English-speaking (as opposed to Mandarin-speaking) audiences.

Universality claims are sort of traditional to 'icon' systems, due to the tendency of their creators to fail to realize that their own culturally-based associations aren't universal. But Xu Bing is deliberately addressing the culturally-specific references of a people not his own; I don't think he's unaware that these icons aren't universal.

For example, the fifth glyph in the first line is quite specifically a reference to 'broken heart' — which is an English-language colloquialism for the way people feel when love is lost, itself a reference to the European idea that love is somehow associated with the blood-pumping organ. Would the concept in a Mandarin-speaking culture be expressed in a way that maps to that same symbol? If not, then why would Xu Bing think this is universal?

Ray

ajay said,

December 6, 2012 @ 11:16 am

For example, the fifth glyph in the first line is quite specifically a reference to 'broken heart' — which is an English-language colloquialism for the way people feel when love is lost, itself a reference to the European idea that love is somehow associated with the blood-pumping organ. Would the concept in a Mandarin-speaking culture be expressed in a way that maps to that same symbol?

But it isn't, really. That's not a picture of a heart broken in two. That's a picture of the stylised Western symbol that means "love" broken in two. An actual heart looks quite different from that, and if you drew an actual heart (a reddish-brown blob with tubes coming out of the top) then most Westerners wouldn't understand it either.

Philip Spaelti said,

December 6, 2012 @ 11:43 am

@Ray: Here is a question; how does the idea of writing originate?

Writing originates when people discover the phonetic principle.

Mike Fahie said,

December 7, 2012 @ 2:03 pm

Jeroen, I like your translation, but after looking at Victor's link, it seems to be a much more direct, almost 1-1 translation of english. He uses parentheses for the whole email (4th icon 1st line until the end of the 6th line). The hardest series of icons for me are the first 3, because it seems clear that he's trying to say "Green sent this mail:", but I don't know what the eye means. I also don't know what that mountain means but I think I get the gist:

Green sent an email: "My heart is broken. My girl left me. She found another man! I can't stop thinking about her – the time we met, when we kissed, our intimacy. I'm so sad. Can you go for coffee at 9? I can' stop crying ….. Green"

Black reads the email and thinks "Greenette is such a bitch!" He replies to the email: "That time is great. We'll fix you up! … Black."

Sockatume said,

December 10, 2012 @ 7:45 am

I'm not so sure that the "broken heart" symbol passes as a broken heart. To me, it looks a lot more like a heart with a lightning bolt on it, which would make it the representation of a defibrillator:

https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=defibrillator+symbol&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-GB:official&client=firefox-a

At any rate if we build upon commonly-accepted and shared symbols rather than inherently comprehensible icons, doesn't the whole process just reinvent language? Wouldn't the subsequent development of the language just render the symbols into more efficient abstractions in either case?

Random Bystander said,

December 11, 2012 @ 4:55 pm

I really like the "embedding" of deponent clauses in braces. It looks surprisingly clear and readable.

Andrew Atkin said,

December 24, 2012 @ 7:31 pm

In terms of universality, the artist has made very clear that he did not create any of these icon symbols. This is vitally important, as the reason fully artificial languages such as Esperanto have never succeeded is that they created their own sterile ecosystem without any organic input.

The artist cataloged these ~25,000 symbols/icons mostly from airports and other international "signage". As such, it's quite a mix. He's writing the first narrative "literature" with these symbols, like a "Beowulf" of sorts. It's the logical next step.

Now, can you discuss deep philosophical concepts with this symbology? Of course not. The caves at Lascaux were simple hunting stories. Let's ask this question, which is what led me to believe that iconji.com and Blissymbolics were on the wrong track…

Why do people who do not speak each other's language want to write/communicate with each other. The example with Iconji is a unilingual English speaker spending 5 minutes asking a unilingual Chinese to meet for coffee at 4pm. Why on earth would someone want to do that? What would be discussed? It would take forever without an interpreter.

Let me tell you what history says. It says, when you meet a foreign culture and can't communicate, the first thing you will want to discuss is trade. This language is great for that. I'd gladly use this for trade or even video game chat and watch it from there. An advantage is that the fully illiterate can read this as well. It does require numeracy, however.

I think this work is vitally important. It's more important than any of the 900 artificial language attempts which have been made (including Esperanto).

Bertilo Wennergren said,

February 28, 2013 @ 12:08 pm

"the reason fully artificial languages such as Esperanto have never succeeded is that they created their own sterile ecosystem without any organic input"

Do you even know anything about Esperanto's "ecosystem"?