Too few words to describe emotions

« previous post | next post »

At about 22:45 of the BBC discussion program The Moral Maze, Natasha Devon asserts

Well it- I- again, one of the problems is language, actually, because in English, we have a very limited emotional vocabulary. When you look at other languages, they- they have a much broader amount of words that they can use to describe their emotions and their mental health. So, if I say to you ‘I’m feeling anxious’, that could be anything from common or garden anxiety right through to an anxiety disorder. And one is a medical issue and the other is not.

E.Z. Granet, who sent the link, comments

My initial reaction was one of mild offence, as this program was focused on rising suicide and self-harm rates in Britain, and Ms Devon seemed to be blaming this quite serious social problem on the fact that English inhibits self-expression. My second reaction was to be linguistically intrigued, as I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone express the common “no word for X” fallacy about their own native language! One would think that someone who worked in mental health would have plenty of experience with precisely how expressive English can be…

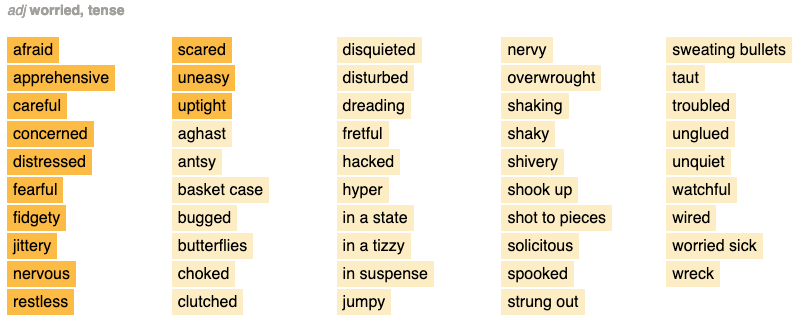

In response to "anxious", thesaurus.com offers 42 alternative choices of words or short phrases:

The DSM chapter on "Anxiety Disorders" gives a long and detailed discussion of symptoms and circumstances, comprising more than 29,000 words.

Despite these linguistic and analytic resources, it's clear that most people find it hard to describe their mental state in a clear way, even to themselves, and that it's usually harder for them to understand other people's self descriptions. But is this the fault of the English language? And is it really true that "other languages … have a much broader amount of words that they can use to describe their emotions and their mental health"?

[Added to the "'No word for X' archive"]

Laura Morland said,

February 12, 2019 @ 7:10 pm

I'm with E.Z. Granet — I live in France half the year, and have not found that the French possess more than 42 options to describe a state anxiety. In fact, I'd put money on them having somewhat fewer.

Looking at her given name makes me wonder: is Natasha Devon perhaps Russian? Whether she is or not, does Russian have a considerably larger pool of words available to describe anxiety?

(Considering what the Russian people have had to endure over the centuries, perhaps they do.)

Victor Mair said,

February 12, 2019 @ 7:50 pm

Sometimes one wants a word that encompasses a broader range of feelings and emotions, sometimes one wants a word that expresses a narrower range of feelings and emotions. "Anxious" fits the broader range rather well, and those 42 alternatives listed above take up other points on the anxiety spectrum quite effectively.

Jenny Chu said,

February 12, 2019 @ 7:51 pm

Often, when people blame language, what they are really blaming is their own inability to use it, or, perhaps, their lack of familiarity with the underlying concepts.

Viseguy said,

February 12, 2019 @ 8:32 pm

Ms. Devon's statement strikes me as arrant nonsense. I wonder what her background in "other languages" is.

Even if English had zero words for "anxiety" or other emotions, its speakers would still have other, arguably more powerful ways to express them — facial expressions, non-verbal vocalizations, laughter, tears, fighting, fleeing, etc. Reductio ad absurdum aside, the challenge, even for highly verbal people, isn't a paucity of words. It's, as Jenny Chu suggests, translating these psycho-physiological experiences into words that adequately convey their meaning and power. That's why we need poets, novelists, playwrights, actors, directors and so on.

But perhaps dear Natasha misspoke, or just needed something to say. It can't be easy talking on the radio.

Chips Mackinolty said,

February 12, 2019 @ 8:51 pm

Apart from the nonsense from Ms Devon, translation of emotional/mental health/etc states is notoriously difficult … and a failure to do so can be devastating. The Ngaanyatjarra-Pitjantjara-Yankunytjara Womens Council in central Australia has been doing groundbreaking work with senior language speakers working up translations from their languages to English (and back) with growing success in the field of mental/emotional health.

Trogluddite said,

February 12, 2019 @ 8:55 pm

Whether the hypothesis is true or not, and I strongly doubt it, the example is very poor. There is no reason to think that the experience of being anxious is any different for a person diagnosed with an anxiety condition – the diagnosis is given because the degree of anxiety is modulated by atypical thought processes or triggered by atypical stimuli. Choosing some other word than "anxiety" to label the emotional state would make it no easier to determine the presence of a mental health problem, even for a psychologist.

Lars said,

February 12, 2019 @ 11:06 pm

I can attest, contrary to Mr. Granet's supposition, that the "no word for X" fallacy is very much used of Danish by native speakers.

Peter Grubtal said,

February 13, 2019 @ 1:22 am

The debate about Eskimo words for snow could be illuminating here.

But what an ill-reflected remark. You'd have to start by looking at the UK suicide rate in international comparison. In fact, it's relatively low. Does that prove then, contrary to what Ms. Devon said, that English (UK) is relatively rich in expressions for emotion?

Bathrobe said,

February 13, 2019 @ 1:45 am

The thesaurus has missed on edge. Or my nerves are bad tonight (T. S. Eliot).

Or 'highly strung'.

But many of the words given in the thesaurus are unsuitable for this kind of occasion (e.g., 'basket case', 'worried sick', 'have butterflies', 'sweating bullets'). Perhaps Ms Devon isn't talking about the total vocabulary that is available in the English language, but the vocabulary that speakers feel is available to them in ordinary life. It doesn't come naturally to all people to express their emotional state in precise terms. You could hardly expect people to say "I'm feeling unquiet at the moment" or "I'm feeling solicitous". In fact, "I'm feeling down" might be more appropriate — suitable for use by an ordinary person in ordinary language AND expressive of anxiety.

E Z Granet said,

February 13, 2019 @ 2:31 am

@Lars

Fascinating! I would absolutely love to hear some of the "no word for X" beliefs Danes have about their own language (reflexive myths?).

Gruen said,

February 13, 2019 @ 2:54 am

@Bathrobe Even if she meant to refer to personal vocabulary (which seems unlikely given she implicated the English *language* rather than the English people), it still raises the question as to whose lexicon is so intricate and nuanced that they could express myriad shades of each possible emotion, and at that in such a way as to be unambiguous to interlocutors. Case in point, I have always taken "feeling down" to be an expression of melancholy and not anxiety.

Gruen said,

February 13, 2019 @ 3:21 am

I would also agree with @Trogluddite that no language could distinguish "healthy" and "pathological" emotion, presuming a real distinction even exists, but that's drifting away from linguistics into the realm of psychology and philosophy.

Smut Clyde said,

February 13, 2019 @ 3:47 am

"Figure 2 gives an overview showing the general structure of

the taxonomy. The taxonomy itself is presented in Tables 2

through 7. It contains 525 terms. Five of these are found in

more than one place because they have two distinct senses.

Fifty-two terms could not be placed."

From "A taxonomic study of the vocabulary of emotions" (Storm & Storm, 1987).

Dominik Lukes said,

February 13, 2019 @ 4:22 am

The fallacy is more that words are the key determiner of what people can talk about. Regardless of the lexical availability, English has many more socially acceptable ways of talking about personal emotions than some other cultures. E. G. Russian is quite expressive when it comes to emotion but they are not as freely aired.

A Berwick said,

February 13, 2019 @ 4:53 am

The key failing of the "No word for X" fallacy is the implicit idea (which is never vocalised, because speaking it would reveal it's idiocy) that if that there is no single word for a particular entity/concept, then it either must not exist or have little relevance in the society where that language is spoken. German has 'schadenfreude' and it's easy to crack the obvious joke about German sensibilities – "Of course THEY have a word for that!", but let's not pretend there are all kinds of people across the world who take pleasure in the pain of others. And let's not pretend that because there is no single word 'going to the store to buy coat hangers for the first time in years and being annoyed because you thought your previous batch would sufficient forever' – it's not something we are able to experience. I don't lie in bed all day because there's no single word to describe getting out/getting up/starting my day in the usual manner.

Keith said,

February 13, 2019 @ 5:52 am

Ms Devon certainly doesn't have a Russian accent, but rather a very typical Southern English accent, and a quick web search turns up some useful background information about her work in trying to improve the mental health of teenagers and young adults in the UK.

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/may/13/sacked-childrens-mental-health-tzar-natasha-devon-i-was-proper-angry

Trying to guess what was going through somebody else's mind at a particular moment is always risky, but I think that she is confusing the fact that the young people she has worked with have difficulty in verbalising their emotions, with a lack of vocabulary in the language. Maybe she has read some articles that claim that other languages have a wider vocabulary, and a slightly altered version of that memory has sparked her declaration.

And in response to Viseguy, speaking on the radio must be very difficult indeed. I listen to BBC Radio 4 (the station that broadcast the snippet) fairly frequently and I have on several occasions had to turn it off because of the speakers' inability to speak fluently and intelligently. Phrases are begun, are re-started part way through, are abandoned; the speaker hesitates, stutters, sprinkles "well, yes, I mean," into almost every sentence…

The signal to noise ratio is sometimes so bad as to make listening pointless.

Bathrobe said,

February 13, 2019 @ 6:22 am

@Gruen

So you feel that most speakers, including suicidal ones, draw a hard and fast line between anxiety and depression?

Tom Dawkes said,

February 13, 2019 @ 7:29 am

Tim Harford's BBC Radio 4 programme "More or Less" had a feature on this last week (8 Feb 2019): see https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0002cn1.

Philip Taylor said,

February 13, 2019 @ 7:46 am

Keith ("I listen to BBC Radio 4 […] frequently […] [and the] signal to noise ratio is sometimes so bad as to make listening pointless") — Ah, you have been listening to the 18:30 so-called "comedy" slot. Never has the word "comedy" been so flagrantly abused …

Tom Dawkes said,

February 13, 2019 @ 7:57 am

@Keith

I agree that there's a lot of incoherency in what many people say on Radio 4 but Tim Harford's programme is a model of clarity and presentation — not to mention his colleague, Ruth Alexander…

raempftl said,

February 13, 2019 @ 8:48 am

@ A Berwick

"German has 'schadenfreude' and it's easy to crack the obvious joke about German sensibilities – "Of course THEY have a word for that!"

You mean because it is obvious that they think that schadenfreude is offensive behavior and therefore they need a word for telling people off when they show it while English speakers see no wrong in schadenfreude behavior and therefore don't need a word to comment on it? :-)

Alex said,

February 13, 2019 @ 9:32 am

What @Keith said.

"… the young people she has worked with have difficulty in verbalising their emotions …"

And it's not just young people, although it's more difficult and confusing the younger you are. As someone diagnosed with a particular type of anxiety disorder and severe, treatment-resistant, unipolar depression, I know that it can be difficult to convey to other people (and to myself) what I'm experiencing. Good, experienced and/or knowledgeable mental health professionals can pick up on what patients are trying to express; other professionals and non-professionals–not so much.

Two additional points: regarding the latter statement about health professionals, there was a medical doctor in my university's computer science graduate computer lab who was researching expert systems to diagnose illnesses. (This was c. 1980.) He wrote a short note to a related journal saying that, despite his interests, he felt that expert systems would never replace a good family doctor. The example he gave was of a long-time, elderly patient who comes in and says, "Nothing really wrong, just a bit of a cold". The doctor, having a history with the patient, can infer the deeper implications of what the patient said, without the need for more descriptive words in the language.

Second, a mental health patient may not be aware of the full extent of their problem(s). In the 1990s, I was put on a medication that completely, but temporarily, relieved the symptoms of my anxiety disorder for a few months before losing its effectiveness. A whole slew of behaviors used to cope with the disorder dropped off. Many of the behaviors I was unaware of, apparently having subconsciously or unconsciously added them to my repertoire of coping mechanisms.

A Berwick said,

February 13, 2019 @ 10:35 am

@ raempftl

You got me! I suppose the same logic explains 'Lederhosen'? Not sure if that's typical German compounding, as it refers to a particular style of leather breeches. Or maybe all German breeches are like that.

J.W. Brewer said,

February 13, 2019 @ 2:21 pm

When it comes to physical health, most patients' ordinary-language lexical resources are probably unhelpfully imprecise when it comes to relating to a physician the exact nature of their aches, pains, sniffles, etc. with the degree of precision that would facilitate the most accurate diagnosis and treatment. Physicians have to either develop the skill of drawing out additional detail via focused questioning or side-step the need self-reporting by using some piece of technology to get a more accurate reading of temperature or blood pressure or what have you than the patient's self-narrative would provide. Why we would expect a more precise lay vocabulary for self-reporting unpleasant emotional/mental symptoms than for self-reporting unpleasant physical symptoms?

Trogluddite said,

February 13, 2019 @ 2:56 pm

@Alex

I concur entirely. Psychologists have a clinical term for such lack of ability to recognise and communicate emotions, as a dimension of personality; 'alexithymia'. Readers who know their Greek etymons may notice that, somewhat ironically, the title of this very thread makes for a pretty close gloss.

I fall towards the severe end of this dimension, possibly as a consequence of being autistic, and it can create serious problems in interactions of all kinds, including talking therapies, or even gaining access to treatment at all. When I say that I don't know how I feel, it is often genuinely the case, and people who know me well can often deduce my emotional state before I am aware of it myself. I have seen several therapists who incorrectly assumed that it was an indication of repressed trauma or lack of will to engage with the therapy (though these problems did indirectly lead to an autism diagnosis in middle-age.)

Therapists trained to work with autistic patients have, however, been able to help me improve my emotional self-awareness and communication. This has not required me to learn any new vocabulary, nor any other language skills; rather, it involved learning to associate sensations with words that were already perfectly familiar. Good psychotherapy is the answer, not language classes.

Philip Taylor said,

February 13, 2019 @ 3:14 pm

JWB ("most patients lack of precision …"). I have experienced the same when, on more than one occasion, being asked to place the severity of the pain which I was experiencing on a scale of 1 to 10. Give that most of us (thank God) have never, and will never, experience pain of level 10, it makes the task of estimating one's own pain level rather difficult …

E Z Granet said,

February 13, 2019 @ 4:23 pm

@Philip Taylor

c.f. https://xkcd.com/883/

Kristian said,

February 13, 2019 @ 4:59 pm

Even if there were more words for emotions, it wouldn't solve the problem of describing the severity of an emotion.

I'm a doctor and when I started being on call, I had a major problem with anxiety. I noticed that every other resident also said it made them anxious. It would, indeed, have been very odd to say that one felt no anxiety. However, for some of them that seemed to mean slight unease beginning a couple hours before the shift, for others it meant that they anticipated it for days and vomited beforehand, for some it meant they had to change specialties. So I noticed that saying "I am anxious" or "I am very anxious" conveyed almost no information about the significance of the experience. I also met an older cardiologist who said that he had been practicing for ten years before he noticed how nervous he was at work.

I've never before heard a mental health professional say that there aren't enough words to describe emotions. In fact, they seem to use more basic words to describe emotions than other people, because they are aware that the more specialized these words become the less one knows what people mean by them. Also many therapies are concerned with teaching people to identify "primary emotions" and there are only a handful of them (around 6-8, I gather).

Michael Vnuk said,

February 13, 2019 @ 5:49 pm

On estimating one's own pain level: My son, in his early teens at the time, experienced a medical emergency which was very painful, enough to make him vomit. He said that the pain completely reset his pain scale. Compared to previous incidents, such as fractures and abdominal pain that he had given scores of 7, 8 and 9, he felt that this new pain was about 13. Now he uses that pain as his level 10. But could there be an even higher pain?

(Thanks to school staff, ambulance officers, hospital staff and others, my son was dealt with quickly and professionally. The emergency operation was successful and he was home within 12 hours of the pain first appearing. He only had some pain (much less than 10) and discomfort for the following few days.)

Jonathan D said,

February 13, 2019 @ 6:15 pm

I think Bathrobe has identified the point. I've come across a few people in the 'wellbeing' area who are pushing research that supports the idea that personally using more detailed emotional vocabulary helps an individual to deal with their own emotions better (never mind express them to someone else). I think I even remember a reference to some other culture, where a wider range of emotions words are regularly distinguished. I have no idea how sensible that comparison was, but it seems likely that Devon has conflated this idea with an idea that the language itself is lacking.

Natalie said,

February 13, 2019 @ 8:32 pm

In era of wide spread of social media people using emotion icons to replace the words.. question is how really you can trust those smiles, lols etc…

RP said,

February 14, 2019 @ 5:13 am

"Natasha" isn't even remotely an unusual or foreign-identified name in the UK; no one here would think she might be Russian unless there were other reasons for thinking so.

Moa said,

February 14, 2019 @ 8:10 am

As an non-native speaker, I feel the problem is less the lack of words, but the fact that most English speakers seems to prefer anxiety instead of the multitude of other English words. The most confusing for me is not differentiating between weak anxiety and strong anxiety. Instead people are making clear the kind of anxiety by other means of communication, such as tone or body language, or context. However, this is my problem as a non-native speaker, not a deficiency in the English language.

Coby Lubliner said,

February 14, 2019 @ 9:47 am

Natasha Devon has a Wikipedia page.

shubert said,

February 14, 2019 @ 12:57 pm

In my humble suggestion, it is not "42 alternative choices" but 42 related words.

Even antonyms are related words.

TIC said,

February 15, 2019 @ 8:02 am

I was confused and then chagrined at the time, but now I look back with nostalgic amusement at the day (sometime in the 70s) when, as a wordy if not outright nerdy kid, the word I chose one morning to describe the vague sort of "not quite my usual self" way that I was feeling… It seemed like forever before my mom and grandmom could stop giggling and compose themselves enough to explain why "irregularity" wasn't exactly the right word for the feeling/occasion… (For those where it might not be common, "irregularity", as I was informed, is most commonly used and encountered as a polite synonym for constipation!)…

Also, slightly more on topic, I'll add that it can be problematic that "depressed" and "depression" are often the go-to words for such a wiiide range, if not variety, of feelings/conditions/symptoms/diagnoses… Likewise with "anxious" and "anxiety" — complicated even further by the fact that "anxious" is so often employed where "eager" might be a better/clearer choice…

Keith said,

February 15, 2019 @ 3:31 pm

@Laura Morland

does Russian have a considerably larger pool of words available to describe anxiety?

(Considering what the Russian people have had to endure over the centuries, perhaps they do.)

Now, here's an interesting question… If it turned out to be true that the Russian language had more words around the idea of anxiety, why would that be?

1. The language has all those words because of the hardship that the people has endured?

2. The people has been able to endure that hardship because its language has all those words?

(Oh, and maybe we can argue about singular 'they' and singular 'people' at the same time…)

file said,

February 15, 2019 @ 7:27 pm

The Irish language does not have a single word for the noun 'description'. It does not inhibit us in any way from describing things though,

Barbara Phillips Long said,

February 20, 2019 @ 4:12 pm

Is this also an issue of the size of the person's working vocabulary as opposed to the size of the language's vocabulary? People who don't know a lot of words may struggle to produce nuanced descriptions.

A combination of personal interest, spelling-word instruction, extensive reading, and acquaintances and family members with varied professions and interests gave me a large vocabulary. Much to my chagrin, my adult children don't seem to know as many words as I do, so it wouldn't be surprising to me that teens or people with narrow interests or folks who don't read much have fewer ways to describe their feelings (and may rely on trendy words).

Maybe what Natasha Devon really needs are Jim Borgman's feelings flashcards or a similar product aligned with the DSM's descriptive or diagnostic terms. Many patients can't tell their doctors if an abdominal pain is in the pancreas, the liver, the gall bladder, or the intestines. It takes questioning and examining to discern the medical problem. It sounds like better diagnostic tools, rather than a change to the English language, is what is needed.