Increasingly generative hybrid Technik

« previous post | next post »

Evgeny Morozov, "The Naked and the TED", The New Republic 8/2/2012 (Reviewing Hybrid Reality):

As is typical of today’s anxiety-peddling futurology, the Khannas’ favorite word is “increasingly,” which is their way of saying that our unstable world is always changing and that only advanced thinkers such as themselves can guide us through this turbulence. In Hybrid Reality, everything is increasingly something else: gadgets are increasingly miraculous, technology is increasingly making its way into the human body, quiet moments are increasingly rare. This is a world in which pundits are increasingly using the word “increasingly” whenever they feel too lazy to look up the actual statistics, which, in the Khannas’ case, increasingly means all the time.

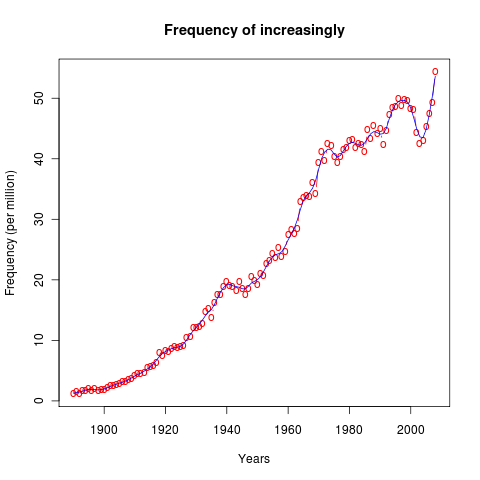

The word increasingly has certainly become increasingly frequent in American books over the past century, with an extra little spurt in the past few years. Here are case-insensitive frequencies from the Google Books American English dataset:

But is it really "the Khannas' favorite word"? In Hybrid Reality, increasingly occurs 36 times in about 19,000 words, for a rate of about 1,895 per million words. So indeed, increasingly is about 38 times more common in this book than in current American books as a whole. Even in the COCA "academic" category, increasingly occurs only at a rate of about 118 per million words, or about 17 times less often than in the Khannas' book.

On the other hand, hybrid occurs 45 times, for a rate of about 2,368 per million words. The current overall rate of hybrid in American books is about 12 per million, so we're talking about a rate increase of 197-fold.

And generative occurs 30 times, for a rate of about 1579 per millions words; generativity adds another 10, for a combined rate of 2,105 per million. Since the current combined rate for these two words in the Google American English ngram dataset is about 3.3 per million, the Khannas are rocking generativ(ity) at about 638 times the current norm.

By the way, you may be wondering, as I was, what generative means for them. Apparently they use it as a synonym for fruitful, or maybe productive:

The underlying principle that will transform our major social systems in hybrid reality is generativity. Generative systems have a nearly endless capacity to connect users and enable them to create new values and outputs. The two finest examples of generativity are also our most universal systems — language and the Internet. As MIT linguist Noam Chomsky argued in the 1950s, human grammar is generative: A few innate rules allow for the construction of deeply rich and varied languages. The Internet too is generative. Jonathan Zittrain of Harvard Law School has explained that the Internet is open to all participants, technically accessible to users producing code and content, and amenable to extension in un-predetermined ways. Such generative characteristics have enabled the Internet to become a kaleidoscope of applications created by a global community of users.

Is the internet "generative" in the same technical sense as "generative grammars" or "generative statistical models" are? For that to be true, there would need to be some well-defined function that would "generate" (and thereby define) the set of all possible Internet applications. I'm not sure that such a function exists; but in any case I'm pretty sure that this is not what the Khannas have in mind.

If I had access to the complete text of their book, I could make similar frequency comparisons for all the words that they use reasonably often, and determine which of them is REALLY their favorite word, in the sense of the word whose rate of use is most unusual in the positive direction.

But I suspect that the winner would be a word that they invent, or rather borrow from another language with an invented meaning, namely technik:

The word “technology” combines the Greek tekhne and logos, symbolizing that technology, like language, is as intrinsic to the human condition as speech. Language, though, does not stand alone; it is part of a larger cultural system. Hence the German word Technik, which denotes not only technologies themselves, but also the skills and processes surrounding them. A century ago, leading Western philosophers appreciated the promise and peril of mass industrialization technologies. Oswald Spengler’s Der Mensch und die Technik: Beitrag zu einer Philosophie des Lebens (1931) proposed to integrate technology into a philosophy of life, arguing that Technik is a process that unites our economic, political, educational, and cultural systems. The American sociologist Lewis Mumford, in his Technics and Civilization (1934), emphasized that technology must be more than just objects seen as ends in themselves (monotechnics); it must be a collection of ideas and methods that improve society (polytechnics). Technik unites the scientific and mechanical dimensions of technology (determinism) with a necessary concern for its effect on humans and society (constructivism). Technik, then, is the technological quotient of civilization.

The meanings of classical Greek τέχνη were already pretty clearly "part of a larger cultural system". LSJ glosses τέχνη as (among other things)

art, skill, cunning of hand, esp. in metalworking […]

_____craft, cunning, in bad sense […]

_____way, manner, or means whereby a thing is gained […]

an art or craft, i.e. a set of rules, system or method of making or doing, whether of the useful arts, or of the fine arts […]

treatise on Grammar, […] or on Rhetoric

And the English word technology retains some "concern for its effect on humans and society" — Merriam Webster glosses it as

1 a: the practical application of knowledge especially in a particular area

__b : a capability given by the practical application of knowledge

2: a manner of accomplishing a task especially using technical processes, methods, or knowledge

3: the specialized aspects of a particular field of endeavor

Application, capability, and accomplishing all have implicit agents, who are humans or human groups; and people and social structures are certainly also involved in those "particular areas", "particular fields of endeavor", and "tasks".

As for German Technik, it's true that it means "technique" as well as "technology, engineering" — but it's not clear to me that this makes it mean "the technological quotient of civilization".

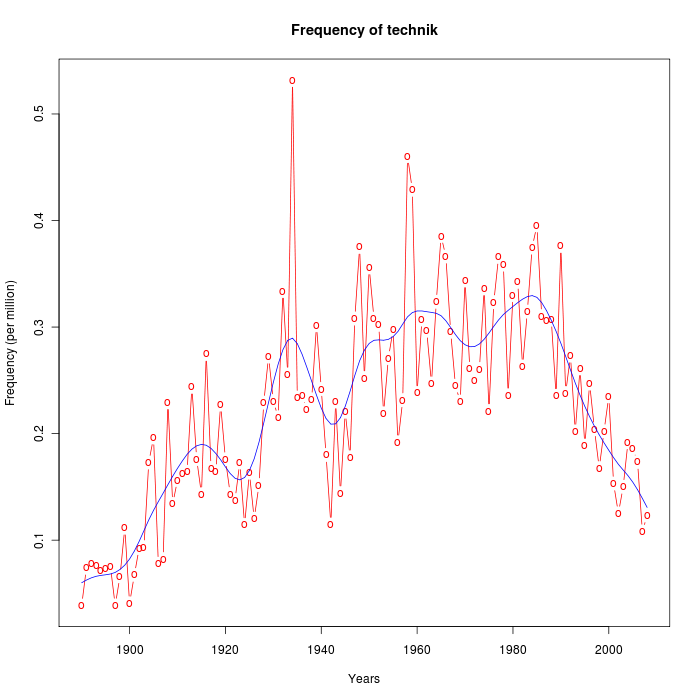

But whatever — there's a long tradition of people borrowing high-status foreign words and giving them a special meaning. And anyhow, the point here is that the Khannas use technik 51 times in their little 19,000-word pamphlet, for a rate of about 2,684 per million. In comparison, the recent rate in the Google Ngrams American English dataset is around 0.2 per million:

Thus the rate in Hybrid Reality is more than 13,000 times greater than the background rate. That's going to be hard to beat.

I wonder, by the way, whether the Khannas have actually read the Oswald Spengler pamphlet that they cite as the source of their Technik-al inspiration, or thought much about its desperate proto-Nazi concern for the fate of "Nordic man". Here's how that work ends (Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life, 1931, translation by Charles Francis Atkinson):

[I]t is out of the power either of heads or of hands to alter in any way the destiny of machine-technics, for this has developed out of inward spiritual necessities and is now correspondingly maturing towards its fulfilment and end. Today we stand on the summit, at the point when the fifth act is beginning. The last decisions are taking place, the tragedy is closing.

Every high Culture is a tragedy. The history of mankind as a whole is tragic. But the sacrilege and the catastrophe of the Faustian are greater than all others, greater than anything Aeschylus or Shakespeare ever imagined. The creature is rising up against its creator. As once the microcosm Man against Nature, so now the microcosm Machine is revolting against Nordic Man. The lord of the World is becoming the slave of the Machine, which is forcing him — forcing us all, whether we are aware of it or not — to follow its course. The victor, crashed, is dragged to death by the team. […]

But all this is changing in the last decades, in all the countries where large-scale industry is of old standing. The Faustian thought begins to be sick of machines. A weariness is spreading, a sort of pacifism of the battle with Nature. Men are returning to forms of life simpler and nearer to Nature; they are spending their time in sport instead of technical experiments. The great cities are becoming hateful to them, and they would fain get away from the pressure of soulless facts and the clear cold atmosphere of technical organization. And it is precisely the strong and creative talents that are turning away from practical problems and sciences and towards pure speculation. Occultism and Spiritualism, Hindu philosophies, metaphysical inquisitiveness under Christian or pagan colouring, all of which were despised in the Darwinian period, are coming up again. […]

The third and most serious symptom of the collapse that is beginning lies, however, in what I may call treason to technics. What I am referring to is known to everyone, but it has never been envisaged in its entirety, and consequently its fateful significance has never disclosed itself The immense superiority that Western Europe and North America enjoyed in the second half of the nineteenth century, in power of every kind — economic and political, military and financial — was based on an uncontested monopoly of industry. Great industries were only possible in connexion with the coal-fields of these Northern countries. The role of the rest of the world was to absorb the product, and colonial policy was always, for practical purposes, directed to the opening-up of new markets and new sources of raw material, not to the development of new areas of production. There was coal elsewhere, of course, but only the white engineers would have known how to get at it. We were in sole possession, not of the material, but of the methods and the trained intellects required for its utilization. […]

And then, at the close of last century, the blind will-to-power began to make its decisive mistakes. Instead of keeping strictly to itself the technical knowledge that constituted their greatest asset, the "white" peoples complacently offered it to all the world, in every Hochschule, verbally and on paper, and the astonished homage of Indians and Japanese delighted them. The famous "dissemination of industry" set in. […]

And so presently the "natives" saw into our secrets, understood them, and used them to the full. Within thirty years the Japanese became technicians of the first rank, and in their war against Russia they revealed a technical superiority from which their teachers were able to learn many lessons. Today more or less everywhere — in the Far East, India, South America, South Africa — industrial regions are in being, or coming into being, which, owing to their low scales of wages, will face us with a deadly competition. The unassailable privileges of the white races have been thrown away, squandered, betrayed. The others have caught up with their instructors. Possibly — with their combination of "native" cunning and the over-ripe intelligence of their ancient civilizations — they have surpassed them. Where there is coal, or oil, or water-power, there a new weapon can be forged against the heart of the Faustian Civilization. The exploited world is beginning to take its revenge on its lords. The innumerable hands of the coloured races — at least as clever, and far less exigent — will shatter the economic organization of the whites at its foundations. […]

For these "coloured" peoples (including, in this context, the Russians) the Faustian technics are in no wise an inward necessity. It is only Faustian man that thinks, feels, and lives in this form. To him it is a spiritual need, not on account of its economic consequences, but on account of its victories — "navigare necesse est, vivere non est necesse." For the coloured races, on the contrary, it is but a weapon in their fight against the Faustian civilization, a weapon like a tree from the woods that one uses as house. timber, but discards as soon as it has served its purpose. This machine-technics will end with the Faustian civilization and one day will lie in fragments — our railways and steamships as dead as the Roman roads and the Chinese wall, our giant cities and skyscrapers in ruins like old Memphis and Babylon. The history of this technics is fast drawing to its inevitable close.. It will be eaten up from within, like the grand forms of any and every Culture. When, and in what fashion, we know not.

Faced as we are with this destiny, there is only one world outlook that is worthy of us, that which has already been mentioned as the Choice of Achilles — better a short life, lull of deeds and glory, than a long life without content. Already the danger is so great, for every individual, every class, every people, that to cherish any illusion whatever is deplorable. Time does not suffer itself to be halted; there is no question of prudent retreat or wise renunciation. Only dreamers believe that there is a way out. Optimism is cowardice.

We are born into this time and must bravely follow the path to the destined end. There is no other way. Our duty is to hold on to the lost position, without hope, without rescue, like that Roman soldier whose bones were found in front of a door in Pompeii, who, during the eruption of Vesuvius, died at his post because they forgot to relieve him. That is greatness. That is what it means to be a thoroughbred. The honourable end is the one thing that can not be taken from a man.

AndrewD said,

August 5, 2012 @ 9:34 am

As they say in the Audi adverts

Vorsprung durch Technik…

Jon Weinberg said,

August 5, 2012 @ 1:13 pm

The Khannas, as the quoted text notes, get the word "generative" from Jonathan Zittrain, whose 2006 paper The Generative Internet begins by describing generativity as "a function of a technology’s capacity for leverage across a range of tasks, adaptability to a range of different tasks, ease of mastery, and accessibility." A technology — like the Internet — that is easy to master and accessible and that allows users to perform a wide range of tasks much more easily is "generative," Zittrain says, in that it will enable users to develop and disseminate new, valuable uses that will lead to further innovation in their turn.

Coby Lubliner said,

August 5, 2012 @ 5:00 pm

It seems peculiar that both Atkinson (the Spengler translator) and Mumford chose "technics" to render Technik, perhaps by analogy with physics/Physik etc., rather than "technology," which by the 1930s was probably far more current (numerous "Institutes of Technology" had by then been so named as the analogues of technische Hochschulen). Mumford, I believe, used "technics" till the end of his long life.

Adam said,

August 6, 2012 @ 4:11 am

Writing about how "increasingly" is becoming increasingly common is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Bert said,

August 6, 2012 @ 4:38 am

@Coby: The "Institutes of Technology" have been named after "technische Hochschule"!? That's funny, because at least two such German institutes have recently been renamed "Institut für Technologie" after, well, the American Institutes of Technology… Times are changing, it seems :-)

Coby Lubliner said,

August 6, 2012 @ 10:55 am

Bert: Most of the technische Hochschulen are now called technische Universitäten, and in many instances the technische has been dropped; this was the case in Karlsruhe, before the recent change to Karlsruher Institut für Technologie, supposedly (according to Wikipedia) in emulation of MIT. But in general it seems to me that Technologie has a narrower meaning than Technik, and most of the Institute für Technologie seem to be specialized research units within universities.