Wright is wrong about sociology as well as basketball

« previous post | next post »

Robert Wright, "The Secret of Jeremy Lin's Success?", The Atlantic 2/14/2012:

One of the most intriguing cultural contrasts between eastern and western ways of viewing the world was documented in experiments by the psychologist Richard Nisbett, some of them in collaboration with Takahiko Masuda. The upshot was that East Asians tend to view scenes more holistically than westerners.

James Fallows, "Jeremy Lin's Secret? It's Not That He's Asian", The Atlantic, 2/15/2012:

Wright asks:

Is it crazy to think that the perceptual tendencies that [these social scientists] documented in East Asians could equip them for this sort of thing?

To answer that question: Yes, it's crazy. More precisely, it's horseshit. I say so in the friendliest possible way, but again: horseshit.

Fallows' argument is based on the facts about how Asians (specifically Chinese) actually play basketball these days. He asks "Overall do they play ball in a way the sociologists might predict?", and answers "Uht-uh" (where I infer that the 't' represents a glottal stop…).

I'd like to intervene in the argument from a different perspective: The psychological research that Wright cites does not support the interpretation he wants to put on it.

I covered the same issues at some length in "David Brooks, Social Psychologist", 8/13/2008. A relevant excerpt:

Question to Language Log: Is it correct that if you show an American an image of a fish tank, the American will usually describe the biggest fish in the tank and what it is doing, while if you ask a Chinese person to describe a fish tank, the Chinese will usually describe the context in which the fish swim?

Answer: In principle, yes. But first of all, it wasn't a representative sample of Americans, it was undergraduates in a psychology course at the University of Michigan; and second, it wasn't Chinese, it was undergraduates in a psychology course at Kyoto University in Japan; and third, it wasn't a fish tank, it was 10 20-second animated vignettes of underwater scenes; and fourth, the Americans didn't mention the "focal fish" more often than the Japanese, they mentioned them less often.

See that post, where I looked into the parts of Nisbett's work that David Brooks cited, for numbers, graphs, etc. at tedious length. Robert Wright, although relying on the whole body of work that I discussed back in 2008, foregrounds a different experiment:

Jim says I'm drawing on the work of social scientists who argue that Asians "perceive reality in a more 'group'-like than individually centered fashion." Not true. I emphasized that I wasn't drawing on "stereotypes about collectivist Asian values." Rather, the finding of these social scientists–and their research is now very well established–is about perceiving dominant foreground images as opposed to background scenes. In the example I cited, the background scene wasn't "a group" but rather a mountain stream.

Anyway the social science finding is that, compared to westerners, East Asians (most experimental subjects have been either Chinese or Japanese) pay more attention to the background scene and less to the central foreground image. I suggested that maybe this more "holistic" perceptual tendency (as the researchers call it) would be an asset to a basketball player as he surveys the basketball court and so might help explain why Lin is such a good passer.

Here's what Wright said about the specific experiment, in his original piece:

In one experiment, East Asians and Westerners were shown pictures and then asked to remember what they'd seen. Westerners tended to recall the dominant foreground image. If the picture was of a beaming tourist with a mountain stream in the background, they'd remember the tourist clearly. The stream? Not so much. East Asians were on balance better than westerners at remembering the background.

He doesn't tell us what paper(s) he's referring to, but one guess is Hannah Faye Chua, Julie E. Boland, and Richard E. Nisbett, "Cultural Variation in Eye Movements During Scene Perception", PNAS 2005. The experimenters recruited

Twenty-five European American graduate students (10 males, 15 females) and 27 international Chinese graduate students (14 males, 12 females, 1 data missing) at the University of Michigan participated in the study. […] Six participants had a hit rate of <0.5 on the object-recognition task, averaged across conditions. These participants' data were excluded in all statistical analyses. One additional European American had poor eye-tracking data. These exclusions resulted in data for 21 European American and 24 international Chinese participants being included in the eye-tracking analyses.

This underlines the first problem that I have with studies like this: they attempt to make generalizations about differences in large groups (Asians vs. Westerners, males vs. females, and so on) on the basis of experiments on small numbers of college students.

It also illustrates a second problem: the selected groups often differ in other ways that may well be relevant to the question being asked. In this case, the Chinese students were young adults who had made the decision to study in a far-off foreign country, had been through the process needed to succeed in doing so, and were presumably aware of being tested in some way that had to do with status as Chinese students in the U.S.. The "European American" students, in addition to being "Western", differed on all of these other dimensions.

And of course we can ask whether any of this is relevant to the case of Jeremy Lin, who was born in Los Angeles, grew up in Palo Alto, went to college in Massachusetts, etc.

Chua et al. showed their subjects

36 pictures of single, focal, foregrounded objects (animal or nonliving thing) with realistic complex backgrounds. The final set of pictures contained 20 foregrounded animals and 16 foregrounded nonliving entities, e.g., cars, planes, and boats (see Fig. 1 for examples of the pictures shown). The set was composed mostly of culturally neutral photos, plus some Western and Asian objects and backgrounds.

The pictures were things like these:

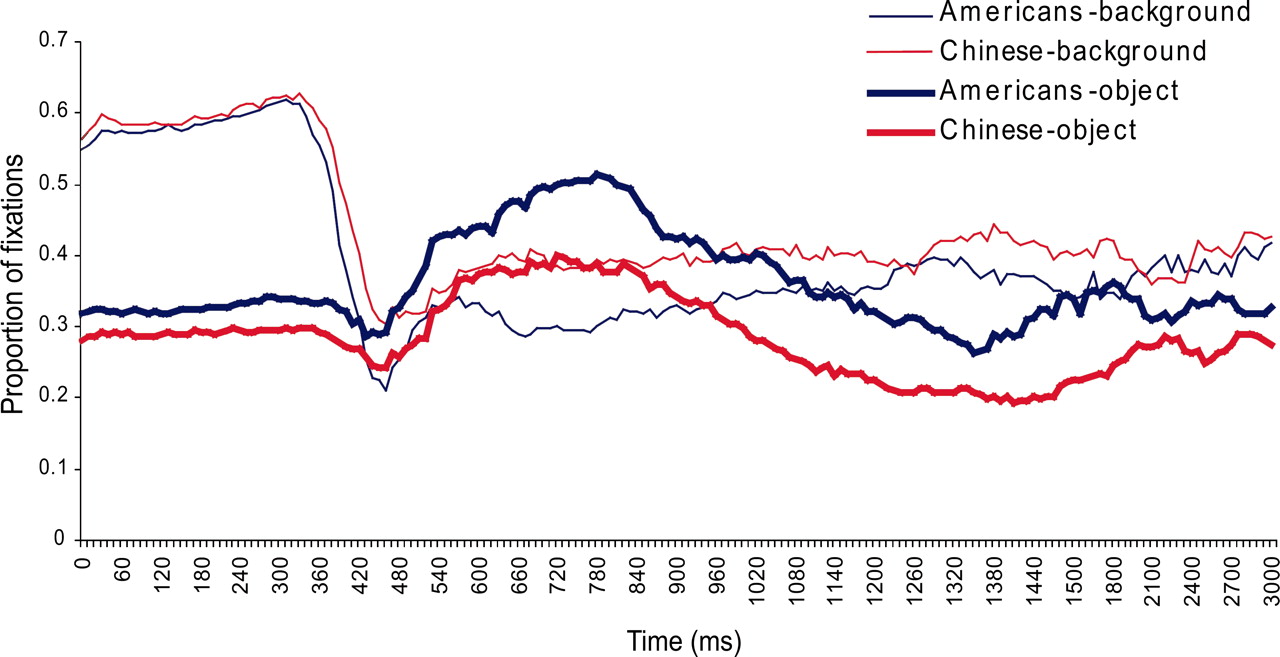

The eye-tracking results looked like this:

Proportion of fixations to object or background, across the 3-s time course of a trial. Data points are sampled every 10 ms for 0-1,500 ms, and every 50 ms for 1,500-3,000 ms, averaging over all 36 trials. The sum of percentages at each time point may not total 100% because, at times, participants were in the process of making a saccade, thus they were in between fixations.

Note that during the first 420 msec., the two patterns were essentially identical. Again, keep in mind that Wright wants to use these results to explain something about professional basketball, where anything that a player doesn't grasp about a scene within 420 msec is likely to be pretty much irrelevant. After the first — culturally identical — phrase,

… an interaction of culture and region was observed, with the Chinese, but not the Americans continuing to fixate the background more than the focal object. Averaging the data from 420 to 1,100 ms, Americans were fixating focal objects at a greater proportion than backgrounds, compared with Chinese. Averaging the data from 1,100 to 3,000 ms, Chinese were fixating more often to the backgrounds and less to the objects, compared with Americans.

Actually, the Chinese students don't start fixating more on the background than on the focal object until after 820 msec. And the average differences between the Chinese and American students in the post-420-msec time period are not very big ones.

After being taken to another room for a distraction task, the subject were brought back for the recall phase of the experiment:

For the recognition-memory task, the original 36 objects and backgrounds together with 36 new objects and backgrounds were manipulated to create a set of 72 pictures. Half of the original objects were presented with old backgrounds and the other half with new backgrounds. Similarly, half of the new objects were presented with old backgrounds and the other half with new backgrounds.

The results looked like this:

(Keep in mind that 6 subjects with accuracy below 0.5 were dropped post hoc from the analysis — we're not told what would have happened to the results if they had been included; but we can guess…)

Here's how Chua et al. describe this:

Mean accuracy rates from the object-recognition phase (22 Americans and 24 Chinese). Data shown refer to correct recognition of old objects, when the old objects were presented in old backgrounds, compared with when old objects were presented in new backgrounds.

Recall what Robert Wright said about it:

In one experiment, East Asians and Westerners were shown pictures and then asked to remember what they'd seen. Westerners tended to recall the dominant foreground image. If the picture was of a beaming tourist with a mountain stream in the background, they'd remember the tourist clearly. The stream? Not so much. East Asians were on balance better than westerners at remembering the background.

Now, maybe he's talking about some other experiment. But as a description of Chua, Boland & Nisbett 2005, Wright is wrong on every point.

It's wrong that "East Asians and Westerners were shown pictures and then asked to remember what they'd seen". Rather, they were shown 36 pictures with single foregrounded objects, and then asked about 72 new picture-presentations whether they'd seen the foreground object before. They were never asked about the background.

It's wrong that "Westerners tended to recall the dominant foreground image. If the picture was of a beaming tourist with a mountain stream in the background, they'd remember the tourist clearly. The stream? Not so much." When the foreground object was presented on the same background as before, the American and Chinese students had identical performance in determining whether they had see it before. When the foreground object was presented on a different background, the American students were a bit better than the Chinese students — about 70% correct rather than 60% correct.

And it's wrong that "East Asians were on balance better than westerners at remembering the background." None of the participants in this experiment were tested on their recall of the background.

Wright's discussion of this work is not nearly as tendentious and confused and careless as David Brooks' was. But it's still tendentious (generalizing from a few Chinese grad students at Michigan to all "East Asians", and from a few European-American grad students at Michigan to all "Westerners") and confused (apparently mis-remembering all the details of the experiment) and careless (not bothering to give a citation or link for the experiment he describes).

So I agree with James Fallows. Robert Wright's account of Jeremy Lin's success is not only horseshit as sports commentary, it's horseshit as social psychology. I say this in the friendliest way possible, of course.

Update — It's possible that Wright was referring to another study: Masuda & Nisbett, "Attending holistically versus analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81(5) 2001. I tend to think that he was talking about the 2005 Chua et al. study, since Masuda & Nisbett 2001 is all about pictures and animated videos of fish, with nothing remotely like tourists or mountain streams in the pictures at all. Masuda & Nisbett 2001 did not look at eye-tracking results, and used Japanese students at Kyoto University rather than Chinese students in the U.S.; but the basic design of the relevant part of the study was the same, and the results were analogous: the Japanese students

… recognized previously seen objects more accurately when they saw them in their original settings rather than in the novel settings, whereas this manipulation had relatively little effect on Americans.

As in the Chua et al. 2005 paper discussed above, these results were marginal at best:

A 2 (culture) × 3 (background) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for accuracy about previously seen objects revealed that there was no significant interaction, F(2, 75) = 2.14, ns.

In order to find a difference, Masuda & Nisbett needed to look at the Japanese and Americans (and new and old objects) separately, in which case the Americans continued to show no effect, but the Japanese were found to be better at recognizing old objects against their former backgrounds as opposed to against new backgrounds.

This paper also looked at subjects' descriptions of fish-tank animations — this part of the research is discussed at greater length in my earlier post, where I point out that a similar sort of analysis-shopping (here looking at mentions in the first sentence rather than overall mentions) was required in order to get the desired (i.e. stereotype-consistent) results.

And of course it's possible that Wright was not just talking through his hat, but was giving an accurate summary of some other study yet. But a search of Nisbett's 2003 book for "mountain stream" and "tourist" turned up nothing, and a search of Google Scholar for {Nisbett "mountain stream"} was similarly unenlightening. In any case, the whole "holistic Asia vs. analytic West" literature seems to me to be similar to the studies discussed here: the effects are small, fragile, subject to several quite different interpretations, and very unlikely to be relevant to variation in basketball styles.

Update #2 — James Fallows has added a note about what Beijing pickup basketball is like ("How Would Jeremy Lin Fare in a Pickup Game in Beijing", 2/16/2012); and another with some lovely quotations about a different era's stereotypes about basketball ("Update on Lin, 'Jewish Dominance' of Hoops, and Ethnic Traits in Athletics and Life", 2/16/2012), e.g. this (from here):

New York Daily News sports editor Paul Gallico wrote in the mid 1930s that basketball "appeals to the Hebrew with his Oriental background [because] the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind and flashy trickiness, artful dodging and general smartalecness." We see how qualities such as cunning and wiliness were posited as the keys to Jewish basketball success and how these kinds of statements were indicative of early 20th century America.

Victor Mair said,

February 16, 2012 @ 7:29 pm

Impressive demonstration of the weaknesses inherent in this kind of sociological and psychological analysis. Not to mention that it is all pretty much irrelevant to Jeremy Lin, who was born and grew up in America, speaks very little Chinese, and writes less.

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3772

Dan Lufkin said,

February 16, 2012 @ 7:57 pm

This is especially poignant if you remember pre-NBA basketball. It was then largely an urban game and, in its early years, dominated by settlement-house Jewish kids. Sportswriters (when they wrote about basketball at all) described how basketball rewarded sneaky, devious play, at which, naturally, Jews excelled.

Here's an interesting link.

When I was in high school (1941-45), basketball was more a girls' game. I was flabbergasted when I got to college and my Nebraska roommate was nuts about the game, which I'd never seen played by grown-ups.

It would be interesting to trace the effect of bringing urban and rural boys together for the first time in the military. I'll bet that Army pickup basketball games played a role.

Dan Lufkin said,

February 16, 2012 @ 8:00 pm

Oops! Moral: Scroll down all the way before mounting soapbox.

Sorry!

Deb Fallows said,

February 16, 2012 @ 8:52 pm

In your comment: Fallows' argument is based on the facts about how Asians (specifically Chinese) actually play basketball these days. He asks "Overall do they play ball in a way the sociologists might predict?", and answers "Uht-uh" (where I infer that the 't' represents a glottal stop…).

Actually, Jim doesn't say "unt-uh" with glottal stop. He actually says it as he transcribes it, with the dental /t/. Chalk it up to his idiolect. He has said it that way for as many years as I've known him (and we've been married over 40 years!).

He also says "leafs" for the plural of "leaf". He knows better, but sticks to his preference there, too. I've stopped asking why.

Deb Fallows

Mandy said,

February 17, 2012 @ 1:30 am

"Fallows' argument is based on the facts about how Asians (specifically Chinese) actually play basketball these days. He asks "Overall do they play ball in a way the sociologists might predict?"

Yes, but how many Asian players (let alone Chinese) are currently playing in the NBA (arguably the best ensemble of skilled-players from around the world)? So this "psychoanalysis" is flawed from the outset because the sample size is too small to allow any meaningful comparison (Wright might consider taking Statistics 101…). There have only been like 3 or 4 Chinese players in the league EVER. If reaching the NBA is indicative of the skill level of Asian basketball players, then they are pretty subpar by world standard – proving that this test is indeed meaningless. Except Yao Ming, these players often bounce from team to team, either because they injure themselves too often or they don't play consistently well.

[(myl) Fallows' post is about Chinese players in the Chinese professional leagues, not Chinese players in the NBA. Basketball is very popular in China, and the sample size is a large one. Fallows' point is that Wright's argument (about the effects of culture on basketball style), if valid, should apply there; but it clearly doesn't.]

One Jeremy Lin does not constitute the norm. Let's not forget that he has an Economic degree from Harvard. Perhaps his exceptional court vision can be explained by his ability to analyze the court situation better than all his teammates. His race has less to do with his success but because of his own hardwork and upbringing.

"How Would Jeremy Lin Fare in a Pickup Game in Beijing"? I think JLin would fit in splendidly by completely changing the dynamics of the team – afterall, this was how the Knicks was playing before Lin came on board. Carmelo Anthony, a big-time ball-hog, is the splitting image of Kobe. The Knicks is now playing in the team mode rather than "be the hero" mentality. Melo is out because of an injury but we will see if he would let Lin touch the ball when he returns!

I say this as a Chinese and a die-hard Knicks fan!!!!!!!

[(myl) Again, the argument that Fallows quotes is not really based on what might happen to Jeremy Lin in a Beijing pickup game. Rather, the point is that the norms of amateur as well as professional basketball in China are not at all as Wright's argument would predict.]

Nathan said,

February 17, 2012 @ 10:41 am

It's amazing how uncritically people still swallow made up crap about "race" in this day and age.

[(myl) In fairness to Nisbett and Wright, both are explicitly talking about culture, not race.]

J.W. Brewer said,

February 17, 2012 @ 12:51 pm

There are lots of sports in which there are historical differences by nation or even continent in style of play (e.g. soccer and ice hockey) or even differences within a nation (e.g. at one point American college football would tend to be more oriented toward either the passing game or the running game depending on which part of the country you were in). I expect in many of these situations it's not that hard to make up a just-so story about how these differences in playing style can be mapped onto pre-existing cultural differences, but that it would be equally easy to debunk such just-so stories — especially since if the styles were reversed an equally plausible just-so story could be conjured up from the always-vast reservoir of cultural-difference stereotypes.

Craig said,

February 17, 2012 @ 2:59 pm

It seems preposterous to even posit that cultural differences based on culture-specific photographic norms would have an impact on how a game that involves physical skill and multiple sensory perceptions is played across cultures. You provide a few convincing arguments as to why these interpretations of the study are horseshit. I would furthermore say that the results of the study, had they been conclusive, might only really tell you a small piece how to put together a photographic exhibit in order to get white American college students to show up in high attendance or how to use cultural icons in the context of a picture to cleverly advertise for your product to Chinese American college students. This equating of basketball to looking at pictures seems to uncritically and implicitly equate the star of the basketball game, the player, with those of us resigned to watching television broadcasts and looking at published images of the game.

Craig said,

February 17, 2012 @ 3:00 pm

Which I guess is the goal of a large amount of sports reporting, linking the players and stars with the fans.

GeorgeW said,

February 17, 2012 @ 3:22 pm

Clearly the evidence does not support Wright's conclusion. But, I don't think it is unreasonable to question whether culture does influence the way people play team sports or that may be cultural differences between Asian-Americans and Euro-Americans that might be in play.

[(myl) Do you really think that Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, etc., are culturally all the same, hyphenated or not? Or that Swedes, Scots, French, Germans, Bulgarians, Spaniards, Jews, etc., brought the same culture to America, or merged culturally in a way that Asian immigrants did not? And how could it be that the NBA's standard style of play should be thought of as "Euro-American", given that a majority of the players are African-American?

Wright's position is not only contrary to the facts of national basketball styles and the details of the science he waves a hand at, it was very sloppy thinking independent of its empirical shortcomings. You're not making it any crisper.]

GeorgeW said,

February 18, 2012 @ 6:30 am

@myl: I agree I should not have been so general in referring to Asian-Americans and I should have mentioned African-Americans who are very prominent in the NBA.

But, I do think that some Chinese-Americans have cultural differences with other American ethnic groups. And, I do think that it is possible that cultural differences can influence the way people play team sports.

These possibilities have apparently not been demonstrated (or refuted) with empirical data.

dsn said,

February 18, 2012 @ 10:59 am

@Deborah

Clearly he is a Toronto Maple Leafs fan!

Jonathan Badger said,

February 18, 2012 @ 12:26 pm

@GeorgeW

Since this is the same Robert Wright who writes popularizations of "evolutionary psychology", I'm not so sure that he *isn't* thinking of genetic differences when he talks about differences in world views.

rick jones said,

February 18, 2012 @ 1:06 pm

Certainly for the first 420 ms the two object lines have the same shape, but if they were the same line, they should cross or touch occasionally. Yet they don't. The two background lines do touch occasionally over that interval (at least within the resolution of the chart and my MkI eyeballs). And the delta between the two background lines doesn't equal the delta between the two object lines. Why?

[(myl) The first thing to keep in mind is that these are curves averaged across 36 trials of 20-odd subjects, rather than plots showing individual performance on individual trials. Individual performance on a given trial is quantal — at any specified time, the subject is looking at some specific place. In order to get curves of the kind shown, you need to count on how many trials a Chinese student was looking at the foreground object at (say) 200 msec (into the 3-second picture presentation), on how many trials one of the Chinese students was looking elsewhere in the picture at that time point, and on how many trials one of the Chinese students was in the middle of a saccade and thus not looking anywhere at that point.

There are all sorts of curious things that can happen in creating those averaged curves. To start with, because of those saccades, the foreground-looking and background-looking proportions don't add up to 1. And individual differences can have odd effects when they're added into the average. Just as a thought experiment, consider a hypothetical experiment in which 20 subjects from group A and 20 subjects from group B have exactly the same averaged eye-tracking behavior over the first half a second — roughly as shown in the region of the plot that you cite — except that one individual in group A always looks at the foreground object 100% of the time, and never at the background object. This will shift group A's foreground curve from the neighborhood of (.3*20*36)/(20*36) = 0.3 to the neighborhood of (.3*19*36 + 36)/(20*36) = 0.335. One curve will lie systematically above the other, making it seem as if there's a small but systematic difference — but in fact we can't interpret this result as telling us anything significant about a difference between the two groups.

Without access to the raw data, we can't answer your question in a confident way. But there's no reason to think that the explanation would tend to support an overall group difference as opposed to some less systematic effect.]

albert said,

February 18, 2012 @ 6:34 pm

Would love to hear from Richard Nisbett himself on this too. Seems like his work has been repeatedly over-interpreted by columnists.

rick jones said,

February 18, 2012 @ 7:53 pm

Thanks for the followup. Indeed without the raw data it is all speculation, and even if there is an actual difference I've no idea what the implication would/could be. With regards to the thought experiment, if an individual from group A was looking at the foreground image 100% of the time, wouldn't there be a corresponding effect on the background image curve since he was looking at the background image 0% of the time?

[(myl) Yes, if that's all that was going on. But something else needs to be happening as well in the cited data, since the ethnic difference in the background-gaze proportion is much smaller than the ethnic difference in the foreground-gaze proportion (especially during the first half-second or so). This can be true because there's also a third category, namely saccade time, which doesn't count in either category.

The point of my little thought-experiment was to explain why the averaged-proportion time-functions are very different things from the actual behavior of any one subject, and why striking-looking group differences in those time-functions can arise (in small subject pools) in ways that result from a few individual differences, and don't license any general conclusion about the groups.

To get the time-functions shown in their chart, you'd have to do something a bit more complicated than I suggested — but there are indefinitely many ways of distributing the needed counts among subjects by groups, and many (most?) of those would not license any conclusions about group differences.]

Links 2/20/12 | Mike the Mad Biologist said,

February 20, 2012 @ 4:44 pm

[…] A new sequencing technology enters the ring: SHTseq(TM) A tale of two analysts Divided Auckland: Overcrowding a hotbed for infections More Doctors 'Fire' Vaccine Refusers: Families Who Reject Inoculations Told to Find a New Physician; Contagion in Waiting Room Is a Fear Wright is wrong about sociology as well as basketball […]