The "dance of the p's and b's": truth or noise?

« previous post | next post »

Stanley Fish asks ("Mind Your P’s and B’s: The Digital Humanities and Interpretation", NYT 1/23/2011):

[H]ow do the technologies wielded by digital humanities practitioners either facilitate the work of the humanities, as it has been traditionally understood, or bring about an entirely new conception of what work in the humanities can and should be?

After a couple of lengthy detours, he concludes that neither any facilitation nor any worthwhile new conception is likely: the digital humanities

… will have little place for the likes of me and for the kind of criticism I practice: a criticism that narrows meaning to the significances designed by an author, a criticism that generalizes from a text as small as half a line, a criticism that insists on the distinction between the true and the false, between what is relevant and what is noise, between what is serious and what is mere play.

In other words, he agrees with Noam Chomsky that statistical analysis of the natural (or textual) world is intellectually empty — though I suspect that they agree on little else.

One of Prof. Fish's detours is this:

Halfway through “Areopagitica” (1644), his celebration of freedom of publication, John Milton observes that the Presbyterian ministers who once complained of being censored by Episcopalian bishops have now become censors themselves. Indeed, he declares, when it comes to exercising a “tyranny over learning,” there is no difference between the two: “Bishops and Presbyters are the same to us both name and thing.” That is, not only are they acting similarly; their names are suspiciously alike.

In both names the prominent consonants are “b” and “p” and they form a chiasmic pattern: the initial consonant in “bishops” is “b”; “p” is the prominent consonant in the second syllable; the initial consonant in “presbyters” is “p” and “b” is strongly voiced at the beginning of the second syllable. The pattern of the consonants is the formal vehicle of the substantive argument, the argument that what is asserted to be different is really, if you look closely, the same. That argument is reinforced by the phonological fact that “b” and “p” are almost identical. Both are “bilabial plosives” (a class of only two members), sounds produced when the flow of air from the vocal tract is stopped by closing the lips.

There is more. (I know that’s not what you want to hear.) In the sentences that follow the declaration of equivalence, “b’s” and “p’s” proliferate in a veritable orgy of alliteration and consonance. Here is a partial list of the words that pile up in a brief space: prelaty, pastor, parish, Archbishop, books, pluralists, bachelor, parishioner, private, protestations, chop, Episcopacy, palace, metropolitan, penance, pusillanimous, breast, politic, presses, open, birthright, privilege, Parliament, abrogated, bud, liberty, printing, Prelatical, people.

Even without the pointing provided by syntax, the dance of the “b’s” and “p’s” carries a message …

The section that Fish cites comprises three paragraphs in the middle of Milton's essay. Flouting Fish's disdain for quantification, I observe (on the basis of a couple of minutes of programming) that these three paragraphs contain 1836 consonant letters, out of 50,433 in the whole work. Within that span, 125 of the consonant letters are p's or b's, or about 6.8%.

Is this "a veritable orgy of consonance and alliteration"? Well, we can recast that question in a way that Fish would doubtless reject: Among the 50,433 consonant letters in the whole Areopagitica, 2,938 are p's and b's, or about 5.8%; is the extra percent in Fish's selected segment meaningful?

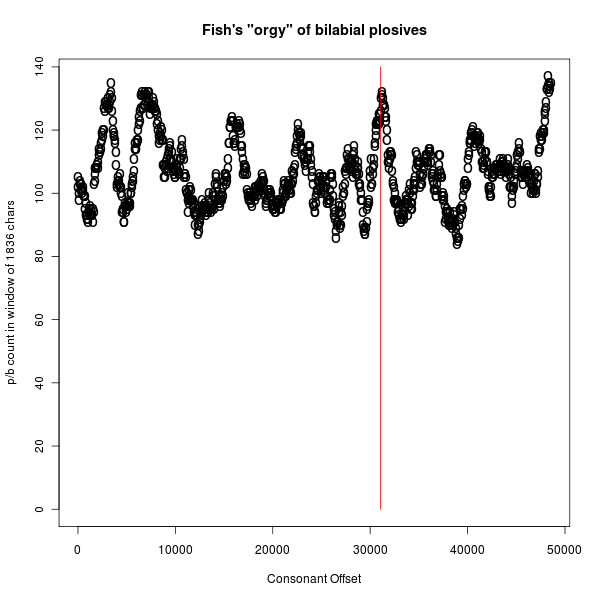

Here's a plot of the p/b count in similar spans throughout Milton's essay, with a vertical red line indicating the region that he selected:

As you can see, these paragraphs are definitely a local peak of bilabial plosivity. But there are nine or ten other peaks, some bigger — do those peaks also indicate regions where "the pattern of the consonants is the formal vehicle of the substantive argument"?

Frankly, I doubt it. In the region that Fish chose to make his point, the topic happens to be enriched with religious-hierarchy words containing p's and b's: prelaty, pastor, parish, Archbishop, parishioner, episcopacy, palace, prelatical, etc. If we look at the end of the essay, which is even more p-b-dense, we find that again it's because of a topical area that happens to be enriched in words like press, published, printed, printer, printing, prevention, policy, purpose, prohibiting, power, book, books, bookselling, libellous, liberty, forbid.

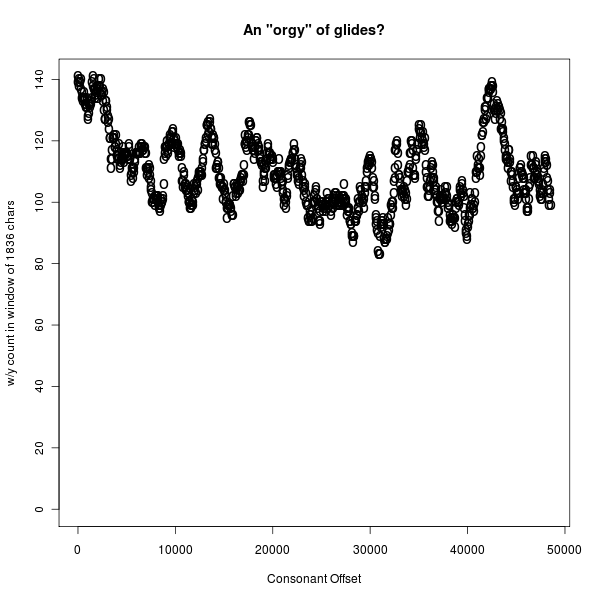

Is this kind of various in local consonant density special to p and b in this work? Not at all — here's a plot of the local density, in a similarly-sized region, of counts of the letters 'w' and 'y'. (I chose them because together they occur 3,032 times in the Areopagitica, about as often as p and b do.)

As expected, the number and relative height of local peaks is similar to what we saw for 'p' and 'b'.

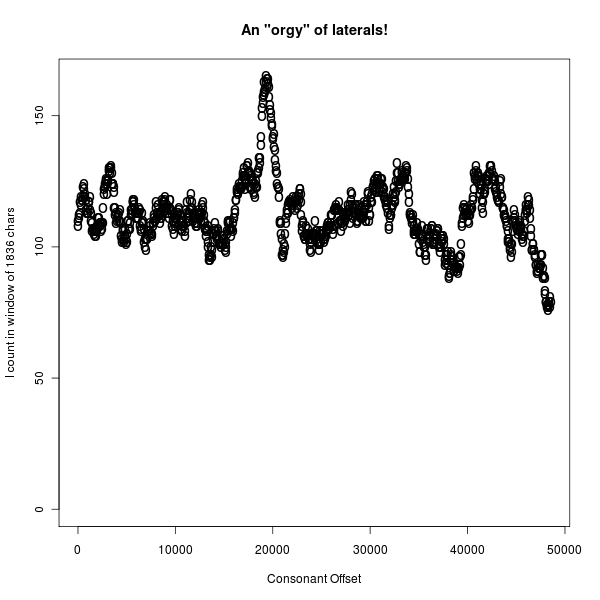

And here's the plot for the single letter 'l', occurring 3,069 times in the Areopagitica, which works up a veritable froth of lateral lasciviousness around consonant offset 19,350:

What does this all mean, if anything?

Prof. Fish begins with an "insight" about the alleged dance of p's and b's surrounding Milton's assertion that "“Bishops and Presbyters are the same to us both name and thing". Despite the paradoxically semi-quantitative nature of his idea, he presents it as an example (though clearly not a very interesting one) of the kind of literary analysis to which "digital humanities" methods are not relevant, the kind of "criticism that insists on the distinction between the true and the false, between what is relevant and what is noise, between what is serious and what is mere play". But it seems to me that a trivial application of statistical methods, humanistic or not, suggests that his idea is probably "false", "noise", and "mere play". Have I missed something?

Cameron Majidi said,

January 26, 2012 @ 11:46 am

I think what Milton likely meant by "Bishops and Presbyters are the same to us both name and thing" was not that the words are phonetically similar, but that the names were once (and might as well still be) interchangeable. Scholars have long held that, in the terminology of early Christian churches, the people referred to as "presbyteroi" are the same group as those referred to as "episkopoi".

Sara T said,

January 26, 2012 @ 11:56 am

Have you missed something? Indeed you have! Notice how 'bilabial plosive' and 'lateral' are both full of the phonemes they describe. 'Glide', on the other hand, is found lacking. I propose an immediate effort to rename them 'wayigs' or some other wayigful word.

dw said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:05 pm

@Cameron Majidi:

Indeed: in Milton's "Prelatical Episcopacy", which predates "Areopagitica", he writes that a Bishop and and A Presbyter is all one both in Name and Office, citing the New Testament.

dw said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:14 pm

Fish also writes in the same article (parodying himself?),

'The stressed word in this climactic sentence is “opposite.” Can it be an accident that a word signifying difference has two “p’s” facing and mirroring each other across the weak divide of a syllable break?'

Thank God Latin had voicing assimilation, or the word would have been "obposite", which would no doubt have meant something even more profound to Fish.

Pflaumbaum said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:30 pm

May I ask a phonology question that's not necessarily relevant to Fish's article? I guess I'll find out…

Is the voicing contrast in the /b/ of Presbyters considered to be neutralised after the /z/, as it is in the /p/ after the /s/ of spitters?

Jerry Friedman said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:44 pm

I'm surprised to see Fish imply that statistical methods are useless for distinguishing what is relevant from what is noise, and shocked to see any contemporary scholar of the arts referring to "mere play" (emphasis mine).

[Why "imply" but "referring"? I'm not sure, but this time I'm going with my internal representation of English.]

I think Milton had a much better argument when he said "presbyter" was the same as "priest".

Now to the point. I think, without data, that arguments of the type Fish makes can be valid in principle and are not necessarily refuted by the kind of statistical analysis MYL makes. If "Bishops and Presbyters" really does call attention to 'p's and 'b's, then a preponderance of 'p's and 'b's in the following passage might be noticeable to a reader. I'd say you need a statistical analysis to support the preponderance, not just a list of words, and Fish shouldn't have left that task to MYL. The fact that the peak isn't unusual as peaks go doesn't necessarily detract from this if the author has called attention to this peak. Also, Milton could have hoped that the final peak in 'p's and 'b's would help readers remember his powerful p-b passage pointing up the baneful resemblance of Protestants' practices to the Papacy's.

The other argument is that a lot of the bilabial plosives are natural to the subject. First, Milton could have avoided some of them. In Fish's list, I think there are possibilities such as

books = writing

parishioner = congregant, layman

private = several (at the time, I think)

chop = trade, exchange

pusillanimous = cowardly, dastardly

breast = some other metaphor, such as "closet"

open = free

birthright = right

abrogated [could be omitted]

bud = flower

Prelatical = Clerical

Second, he might have decided to play on the sounds in "bishop" and "presbyter" after he noticed that the following passage would or could be enriched in them.

Third, even in prose Milton may have used the methods of poetry, which I understand to involve taking advantage of the opportunities provided by the language as much as making things work the way one wants. (I've written some poetry, though no one would compare it to Milton's.) In other words, he may have taken his argument in this direction and spent so much time on because he saw a "formal" way to carry it.

However. In practice, in this case, I don't see it. I don't find "Bishops and Presbyters" similar enough in sound to account even partially for Milton's statement that they're the same in name, and I suspect Cameron Majidi has the right idea. Milton may have been enjoying and hoping the reader would enjoy the bilabial stops here, but I don't think they act as much of a formal vehicle for (or sophistic reinforcement of?) his substantive argument.

Jerry Friedman said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:49 pm

I think I meant the "resemblance of Puritan and Presbyterian practices to Episcopalian". Maybe someone will tell me for sure.

KevinM said,

January 26, 2012 @ 12:54 pm

Related is the wordplay in the sonnet "On the New Forcers of Conscience." http://milton.classicauthors.net/PoemsOfJohnMilton/PoemsOfJohnMilton18.html

("New Presbyter is but old Priest writ large.") As I learned it, Milton believed (correctly?) that the words "priest" and "prebyter" shared an etymological origin in the Greek work for "elder," the former being a contraction of the latter ("writ large").

The sense of Milton's attack on Presybterianism is essentially "Tweedledum/Tweedledee," or "Meet the new boss, same as the old boss." The point is underlined by the "Lord/[Bishop]Laud" pun in the first line.

MattF said,

January 26, 2012 @ 1:08 pm

A paradox– Fish is certain he doesn't need methods that deal with uncertainty. That makes perfect sense, in fact.

Mark Liberman said,

January 26, 2012 @ 1:11 pm

Jerry Friedman: I think, without data, that arguments of the type Fish makes can be valid in principle and are not necessarily refuted by the kind of statistical analysis MYL makes.

This is certainly true. Consider S.J. Keyser's argument (from 'The linguistic basis of English Prosody", in Reibel & Schane, Eds., Modern Studies in English, 1969) that Keats' line

How many bards gild the lapses of time

is self-referentially unmetrical. This seems clearly to be true, although it's based on the placement of a single two-syllable word ("lapses") in a single line of a single sonnet.

We could support this idea by looking statistically — and even digitally — at the placement of the stresses in many polysyllabic words in many lines of iambic pentameter, by Keats and others. In fact, scholars have done exactly this. But the plausibility of the original insight doesn't really require this back-up, in my opinion — I would certainly never suggest that insights always require statistical tests or can only emerge from explicit statistical data analysis.

But Fish's argument seems to be that counting things in literary texts can never play a useful role in developing or testing worthwhile critical hypotheses. About this, I can only repeat the maxim that sometimes it takes a really smart person to have a really stupid idea.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 26, 2012 @ 1:23 pm

Building on dw's comment and Fish's pileup of words, "prelate" was a common pejorative of the time for "bishop" from the Presbyterian/Puritan faction of Protestants, and linking royalist prelate with Cromwellian presbyter as equally illiberal would have been a more obviously alliterative way to make the same point. Of course you could add "parson" "preacher" and "pastor" to develop some dramatic theory about p-initial words forming some semantic group like gl-initial words . . . (I assume there's some reason the consonant got voiced when Greek-via-Latin episkopos/episcopus became bishop, or else it would fit as well, and "minister" is also bilabial …)

Jerry Friedman said,

January 26, 2012 @ 1:24 pm

@MYL: I think we agree on a lot. I didn't think you suggested that insights always require statistical tests, and I certainly agree that counting things can play a useful role in criticism. I was specifically disagreeing with this sentence at the end of your post: 'But it seems to me that a trivial application of statistical methods, humanistic or not, suggests that his idea is probably "false", "noise", and "mere play".'

(Not to be contrary, but on the Keats line, I think we do need statistical analysis. As I learned from the references you gave the last time this came up, some poets do allow a two-syllable word with a strong accent in that position, and some don't. So there's still the question of whether Keats did, which I think can only be answered by means of some counting.)

[(myl) OK, you're right, at least in that the background metrical theory could be contested, and needs empirical support of a kind that would be best presented in statistical terms. But I think the insight that the line is self-referentially unmetrical (or at least metrically strained) is true on its face. At least, I was casting around for examples of insights with this property — substitute your own favorite examples if this one doesn't work for you.]

Morten Jonsson said,

January 26, 2012 @ 1:51 pm

@ Mark Lieberman

If Keyser means that the unmetricality of Keats's line depends on that one word "lapses," that isn't quite true (or even true at all, as Jerry Friedman points out). There's more serious stumble earlier than that, with a missing unstressed syllable either before or after "gild." Keats could easily have made it regular by writing something like "How many bards [do] gild" or "How many bards gild [o'er]." But the fact that he didn't suggests that he wanted that effect.

[(myl) There has been quite a bit of discussion in the literature about how many metrical lapses there are in this line, and what they are — I believe in fact that Keyser identified two, though I don't have a copy of his article at hand. But some people, at least, assert that the placement of "lapses" is the only problem. (Since WordPress has an idiotic prejudice against line-initial spaces, I'll use caps to indicate the five strong positions in the obvious analysis…)

How MAny BARDS gild THE lapSES of TIME

The general pattern for English art poetry in Keats' period does not constrain the position of monosyllables, and also doesn't constrain the placement of prosodically weak syllables, but only forbids the placement in weak metrical positions of local stress maxima of polysyllabic words. So on this theory, at least, it's just "lapses" that is wrong.

The placement of "the" is clearly also a sort of clash between the metrical pattern and the natural phrasal stress, but in fact "the" shows up in metrically strong positions quite often in this kind of poetry.]

I also agree that Milton isn't saying that "bishops" and "presbyters" sounded alike–he's saying that the names signify the same thing, not that they're the same name. That seems a pretty basic misreading on Fish's part, which his rigmarole about bilabial plosives only makes more embarrassing.

Xmun said,

January 26, 2012 @ 3:00 pm

@KevinM: You are quite right about "presbyter" and "priest" having a common derivation from ecclesiastical Latin. "Presbyter" is a modern borrowing of the Latin (originally Greek) word; "priest" is the form the word has ultimately taken after centuries of continuous use and the sound changes that go with it. A similar pair is the Spanish "communicar" (communicate), a modern borrowing, contrasted with "comulgar" (to take communion), likewise derived from the Latin "communicare", but gradually altered over the years.

AntC said,

January 26, 2012 @ 3:21 pm

Am I the only one to feel the clunkiness of the first of Fish's sentences that myl quotes? (I had to read it twice to get the sense from the "digital humanities practitioners'" noun pile-up through the interpolated rider.) I thought at first that myl's piece was going to be about the awfulness of his syntax.

The later passages myl quotes are somewhat better, but it's still stodgy going. Are they generally representative of Fish's 'style' (if that's the word)?

I feel the same reaction as from reading Chomsky: this guy has such a tin ear for the language, he ipso facto disqualifies himself from having anything worthwhile to say on the subject.

Academic language about language can still be lyrical, as Language Log regularly shows.

Xmun said,

January 26, 2012 @ 4:49 pm

Correction to my comment: Spanish "comunicar" is of course so spelt, with only one m.

Jon Weinberg said,

January 26, 2012 @ 4:53 pm

Part of the problem here is that Fish identifies the "digital humanities" not as any statistical analysis of literary works, but rather as a particular methodology, featuring statistical analysis, that rejects the approach of formulating and testing hypotheses. He rejects that, he says, because he's old-school and appreciates the value of formulating and testing hypotheses. It's a double shame in that context that he then brings forward a hypothesis that's unsupported, untested, and easily disparaged using, yes, statistical analysis.

Brett said,

January 26, 2012 @ 5:07 pm

What I found most puzzling was the second quoted section by Fish, which seems completely at odds with what I have understood to be his viewpoint on criticism. For example, I would have expected, "a criticism that narrows meaning to the significances designed by an author," to be practically the opposite of what Fish was interested in.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 26, 2012 @ 5:11 pm

This guy http://tedunderwood.wordpress.com/ (whom I'd never heard of until this week when a mutual friend linked to something) has a series of recent posts on Fish v. "digital humanities" and the description of the general theme of his blog as "Historical questions raised by a quantitative approach to language" suggest that some in the LL community might be interested in his take.

Circe said,

January 26, 2012 @ 6:27 pm

"The stressed word in this climactic sentence is “opposite.” Can it be an accident that a word signifying difference has two “p’s” facing and mirroring each other across the weak divide of a syllable break?"

Indeed, it seems to be an accident. A whole chunk of Indian languages, for example, have the word "विपरीत" for "opposite", and I can't fit it to letters "mirrorring each other over a syllable break". And that's just in the Devanagari script (which is much newer than the word itself). Godd luck finding consonants "mirrorring each other over a syllable break" in other scripts and languages.

sedeer said,

January 26, 2012 @ 8:47 pm

From the excerpt provided, it seems to me that Fish is saying the colocation of "p" & "b", not simply their summed frequency:

"what is asserted to be different is really, if you look closely, the same. That argument is reinforced by the phonological fact that “b” and “p” are almost identical."

So wouldn't the correct test be to compare the individual frequencies of "p" & "b" throughout the text and see if there is significantly greater colocation in parts of the text addressing things that are similar but different?

[(myl) There are lots of ways to make Fish's idea more specific, and each could be tested. The text is easily available from various sources, so you could easily figure out exactly what you mean by "colocation" and test whether it's true; though I think you'll be handicapped by the fact that there are no other parts of this specific essay that seem to deal explicitly with "things that are similar but different", although there are several other places with apparently similar or larger joint increases in the frequency of p and b. You can see this by plotting p and b separately, or by plotting the product of p & b — there are three other places where the correlation of p and b is higher than in the region under discussion. Maybe this isn't what you mean, but the burden of proof at this point is on you.

Speaking for myself, I'm convinced that Milton mean something completely different by the cited sentence — along the lines suggested by Cameron Majidi and others — and that the alleged dance of p's and b's is a routine by-product of the words evoked by the local topic.]

While I'm not particularly impressed by the argument Fish makes in the article, I'm also not really comfortable with approaches that are based on throwing statistics at a problem and then coming up with an interpretaiton (as opposed to using statistics to evaluate a hypothesis). That kind of thing always reminds me of Isadore Nabi's "On the The Tendencies of Motion.

möngke said,

January 27, 2012 @ 12:09 am

1. Is consonant frequency the only thing that affects alliteration?

[(myl) When alliteration is required in poetic forms, it's about pronunciation, not spelling; and is generally further restricted to onset consonants, or to onset consonants in stressed syllables, or something of the sort, depending on the language and the tradition. Alliteration as an informal poetic device is still generally about speech and not writing, as far as I know. Fish is vague about what he means by the dance of p's and b's, so it's not obvious how to score various syllabic or prosodic positions; and in the case of p and b, English orthography is a decent proxy for phonology.]

2. Is the statistical method useful when examining sequences defined by "traditional" scholars as alliterative?

[(myl) If by "the statistical method" you mean "counting things as a way of arguing for or against an idea", then scholars of poetic form have been using this method for centuries.]

Leonardo Boiko said,

January 27, 2012 @ 7:27 am

Can it be that alliterations that are salient to humans are harder to quantify, because salience or relevance involves other factors like semantics, pragmatics, context, æsthetics &c.—e.g. the very fact that his p/b orgy is “enriched with religious-hierarchy words”?

Would other people also notice the passage that Fish liked, for the same mysterious reason it was that drew him to it? Would Fish fare better if we did a poll asking readers to find sonorous or euphonic passages in Miller’s text?

Though my literary-criticism side believes even this is besides the point: A large part of the reason I enjoy criticism is precisely its potential to show me new and unexpected readings, to connect dots I’d never think of as related, to reframe noise as signal, to not only make sense but to create sense. In other words, a reading being uncommon is for me a virtue, as long as it’s relevant and rewarding. But this means I embrace the “mere play” that Fish wants to steer away from; the way I see it, if what you aspire for is The Truth, you’d better turn to linguistic science and statistics (which is also an interesting and worthy course of approach, natürlich).

Bill Benzon said,

January 27, 2012 @ 8:39 am

Ah, Stanley, Stanley, what are you saying?

It's difficult to know just how seriously to take this little performance, but it's worth setting it in the larger context of Fish's career as a theorist of methodology. Back in the dark and benighted times of the 1970s he wrote some take-downs linguistic and statistical methods in stylistics which were included in his very influential 1980 collection, Is There A Text in This Class? Elsewhere in that collection he argued his version of the notion that the meanings critics find in texts are the meanings that they themselves put there (as authorised by their local 'interpretive community'). It was his ability to argue that point that put him on the map as a BIG THEORIST.

That, of course, is rather different from the position he's now claiming in this piece, namely that the meaning is put there by the author and that it's the critic's job to find it through arguments that can be right, a good thing, or wrong, not so good. THAT was the mainstream position at mid-20th century; that was the position Fish and others were then deposing.

So perhaps he's changed his mind. Though I note that only a few years ago he was arguing that what critics, such as himself, do is pretty much play around with texts in a way that is unfettered by utility in any way, shape, or form. And that's the glory of it all.

And that DOES seem to be what Fish was doing in his plosives palaver in this piece, playing around.

I note that in one of his excursions in the current piece, Fish argues against one Stephen Ramsay, who "doesn’t want to narrow interpretive possibilities, he wants to multiply them." That is, Ramsey seems to view digital explorations of texts as a means of playing around even more, a comfortable demodernist postconstructive recouperation of post-industrial capitalist technology. So, if Fish is going to position himself against THAT, well, what better position to assume than arguing for truth, justice, and the old intentionalst way?

[(myl) I noticed that Prof. Fish's current writing seems to have become oddly detached from his earlier work. But if meanings are associated with texts by readers rather than by writers, isn't taking note of his authorial inconsistency merely a form of lectorial self-criticism? In any case, I suspect that he doesn't mind, as long as we spell his name right.]

Alex said,

January 27, 2012 @ 11:43 am

This is why I just can't take the humanities seriously anymore. The florid prose, the weird statistics-phobia, the penchant for grandiose unsubstantiat(ed/able) claims and the word "orgy"…

[(myl) But the word "orgy" is the best part!]

Jerry Friedman said,

January 27, 2012 @ 1:18 pm

I like Fish's writing, including "orgy", but it's not my favorite part. In view of what Bill Benzon and Brett have said, maybe my favorite part is that while claiming to eschew mere play, Fish interprets Milton in a way that I see no justification for except playfulness. I do think it's possible that Milton was having some fun at that point.

@Xmun: A similar ecclesiastical doublet in English is "sacristan" and "sexton".

@Circe: Fish's suggestion that Milton's "opposite" isn't accidental is, as I understand it, a suggestion that Milton chose the word "opposite" rather than some other way of saying the same thing (maybe with "contrary" or "reverse") because of the supposed opposition of the two p's. I can't take this any way but as playfulness on Fish's part.

Dave said,

January 27, 2012 @ 2:49 pm

Stanley Fish is a dam' fool, and always has been.

Robin Dempsey, Rummidge University.

army1987 said,

January 28, 2012 @ 5:55 am

Now I want to see a quotation of the /l/ peak at offsett 20000. :-)

[(myl) I think it's just the accidental confluence of a few content words (national, England, ill, gluttony, daily, multitudes, sold, licensing, regulate, etc.) and a rhetorical device involving repetitions of "who shall", "what shall" and so on, as in:

Next, what more national corruption, for which England hears ill abroad, than household gluttony: who shall be the rectors of our daily rioting? And what shall be done to inhibit the multitudes that frequent those houses where drunkenness is sold and harboured? Our garments also should be referred to the licensing of some more sober workmasters to see them cut into a less wanton garb. Who shall regulate all the mixed conversation of our youth, male and female together, as is the fashion of this country? Who shall still appoint what shall be discoursed, what presumed, and no further? Lastly, who shall forbid and separate all idle resort, all evil company? These things will be, and must be; but how they shall be least hurtful, how least enticing, herein consists the grave and governing wisdom of a state.

It's easy to notice the alliterative touches ("rectors of our daily rioting", "grave and governing wisdom"), but the piling up of l's flies under the perceptual radar, at least for me, and I suspect that it's essentially a local accumulation of lateral luck.]

Fish’s Object « Work Product said,

January 28, 2012 @ 4:12 pm

[…] 2: Mark Lieberman at Language Log runs some revealing numbers on the P's and B's in Areopagitica that were part of Fish's set piece.] Advertisement […]

army1987 said,

January 28, 2012 @ 5:12 pm

Indeed, that doesn't sound very alliterative to me. On the other hand, your lateral luck… I think the position of the letter strongly influences my perception, i.e. a piece of text is much more likely to sound alliterative to me if the repeated sound is at the beginning of words (or, at least, in syllable onsets).

Bill Benzon said,

January 28, 2012 @ 5:28 pm

@Jerry Friedman: Yes, of course Milton was having fun. And a reasonable discipline of literary study would be interested in understanding just why such verbal horsing around IS fun. Rewarding the Stanley Fishes of the world for their own horsing around doesn't seem to have a place in such a discipline.

SimonMH said,

January 29, 2012 @ 10:24 am

I think the Keats line is strained only if one starts with an iamb. Trochee, iamb, trochee, trochee, iamb is how I read it: HOW many BARDS GILD the LAPSes of TIME. The trochaic substitution in the first foot sets up an expectation of metrical adventure, which Keats exploits to make pleasing music, and not wild uproar.

Circe said,

January 29, 2012 @ 4:57 pm

Jerry Friedman:

Such "playfulness" by literary critics often reminds of the Issac Assimov story in which Shakespeare is brought via a time machine to a Columbia course on Shakespeare's sonnets, and fails miserably.

DaveB said,

January 29, 2012 @ 6:50 pm

A few thoughts, as an English teacher:

1: It is depressing when I meet kids who've been taught that "laterals sound gentle" or "sibilance is sneaky" or all sorts of other immediately disprovable tosh.

2: That said, I think a discussion of how sound supports sense in a given instance can be valid and thought-provoking. Unfortunately, most critics seem incapable of doing so without allowing the claims they are making to expand beyoond the very limited terrirory that the evidence can support. To my ear, the plosives in the cited passage *are* worthy of mention and analysis, irrespective of whether Milton intended some particular effect. Stanley Fish overreaches massively, but let's not throw the baby out with the bathbrine. As MYL notes, the words at play here are on the whole linked by both sound and sense (unlike in the lateral orgy).

3: I think that there is much more space for Language Log-style analysis in literary criticism, especially if one is attempting to make grand claims that have a quantitative aspect. For example, I remember Helen Vendler's observation that "quietus" is used just twice by Shakespeare: in Hamlet's 'To be or not to be" soliloquy, and one enormously powerful sonnet (just 12 lines, or 14 but with a couplet made up of two pairs of parentheses).

Jerry Friedman said,

January 30, 2012 @ 1:03 pm

@SimonMH: To me too, brought up on Frost and Yeats, "How many bards…" is just a tasty iambic pentameter. As MYL explained above, there seems to have been an unwritten rule, followed by most poets till the 20th century, that the accented syllable in those trochaic substitutions has to be a monsyllabic word (or following a pause, and prepositions get a pass). Thus "GILD the" is normal, but "LAPSes" is highly irregular. Apparently no one stated this rule explicitly until a 1975 paper by the linguist Paul Kiparsky.

@Bill Benzon: I have nothing against horsing around in criticism, and it may be more fun deadpan, but I don't like it when it can fool people into taking it seriously, even if some might enjoy that the most. How this might apply to Fish, I have no idea. (If I seemed more certain a few days ago, either I didn't express myself clearly or I've changed my mind.)

@Circe: Spell his name with one S (unless you're trying to say he was an ass :-). As I recall, by the way, Asimov was convinced after attending a class on his writing that writers could put more into their stories than they were aware of…but still, I agree that some analyses look like they're going too far.

SimonMH said,

January 31, 2012 @ 1:41 am

@Jerry Friedman: Thanks for the link to the Kiparsky paper – very interesting.

John Lawler said,

January 31, 2012 @ 4:36 pm

Fish seems to be mudding the waters. Labial-initial clusters are quite often phonosemantically coherent in English, though this is not generally true for words that merely begin with a simple labial stop.

The initial clusters br-, pr-, bl, and pl- are especially interesting.

Stanley Fish versus the Digital Humanities | FSU Digital Scholars said,

February 1, 2012 @ 2:30 pm

[…] Liberman, Mark. “The ‘dance of the P’s and B’s’: Truth or Noise?” Language Log 26 Jan. 2012. <http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3730>. […]

Digital Humanities, Part 1 | Not Just Coasting said,

February 4, 2012 @ 10:14 pm

[…] This image comes straight from Liberman's data and, as you can see, it's a relatively high usage, but not a globally high usage. Or, to put it another way, it's probably just a coincidence. If you want to read the rest of Liberman's article, it can be found here: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3730 […]