Straw men and Bee Science

« previous post | next post »

If you followed my advice (in "Norvig channels Shannon contra Chomsky", 5/31/2011) and read all of Peter Norvig's essay "On Chomsky and the Two Cultures of Statistical Learning", you may have detected a certain restrained testiness in Norvig's response. The goal of this post is to give a bit of explanatory background, and to suggest why, on the whole, I share Norvig's reaction.

Here's a short passage from Noam Chomsky's invited lecture at NELS 41, 10/4/2010. (Apologies for the poor audio quality — this is a recording that I made on my cell phone. Disfluencies have been edited out of this fragment — a rough but more complete transcript of the entire lecture is here.)

The argument is well, take a look at physics — you know, real science. It's based on observations. But you know, not observations of things in their natural state, like you don't try to say determine the laws of motion by taking video tapes of leaves falling and do massive statistical analysis of them, and so on and so forth. So you do experiments, and in fact a lot of the experiments are thought experiments, including Galileo's classic experiments,and that goes right up to the present. But any experiment ((is)) a high level abstraction, and theory-internal, as everybody who does experimental work knows. [It's the] same ((if you're) studying any other topic, say bee communication. I mean again, ((if you)) take a look at the work on bee science, it involves highly contrived, very intricate experiments that are radically abstracted from natural conditions. Nobody suggests studying bee communication, again, by taking a massive corpus, you know, [a] huge library of video tapes of bees swarming around and doing statistical analysis of it, and getting some prediction about what they're likely to do next.

There are two arguments yoked together here. One argument has to do with the goals of science: Chomsky pushes explanation over prediction, and never mind prediction's occasional intrinsic value (in the case of climate change or asteroid strikes or inflation rates), and its generic value as a check of a theory's correctness. (C dislikes prediction, I think, because he associates it with "statistical language models", which in his long-held view are incapable of describing syntactic structure, much less explaining it.)

The other argument has to do with the methods of science: Chomsky argues for "very intricate experiments that are radically abstracted from natural conditions". His disdain for mere description ("butterfly collecting", as he often calls it), and especially for "observations of things in their natural state", is well known. You can see it in the short passage quoted above, and if you read the rest of the transcript of his NELS 41 lecture, or his other works such as "Linguistics and Brain Science", you'll see that it's a recurring theme.

Let me start by saying that there's a way to take all this that makes it entirely correct. The key motive of science is explanation, and it's often essential to abstract away from the complexities of raw observation, and so on. I took courses from Chomsky as an undergraduate and a graduate student, and I'm grateful for what I learned from him, and for the eminently fair way that he always treated me. But increasingly, it seems to me, he has been elevating his personal distaste for the complexities of the real world into a systematic philosophy. To the extent that others accept these views, it excludes them from participation in (what I think are) the most promising and exciting current directions in the sciences of speech and language.

I'll let someone else address the physics piece of this, perhaps by considering the work that won the 2011 Gruber Cosmology Prize, a collaboration that started with what you could call a "massive corpus of galaxies swarming around":

The particular evidence that motivated the creation of the DEFW collaboration came in the form of a 1981 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics survey of 2400 galaxies at various distances—at the time, an extraordinary census of how the heavens look on the largest scales. (Davis led the project.) What the CfA survey showed was an early hint of what is today called “the cosmic web”—galaxies grouped into lengthy filaments, or superclusters, separated by vast voids.

But "bee science" is something that I know a little bit about, especially the part of it that has to do with bee communication. The father of modern "bee science" was Karl von Frisch, who got the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his work in this area. And von Frisch was no enemy of observing "things in their natural state", and no friend of "highly contrived … experiments that are radically abstracted from natural conditions". In the preface to his popular work Aus den Leben der Bienen, published in an English translation by Dora Ilse as The Dancing Bees in 1954, he wrote:

If we use excessively elaborate apparatus to examine simple natural phenomena Nature herself may escape us. This is what happened some forty-five years ago when a distinguished scientist, studying the colour sense of animals in his laboratory, arrived at the definite and apparently well-established conclusion that bees were colour-blind. It was this occasion which first caused me to embark on a close study of their way of life; for once one got to know, through work in the field, something about the reaction of bees to the brilliant colour of flowers, it was easier to believe that a scientist had come to false conclusion than that nature had made an absurd mistake.

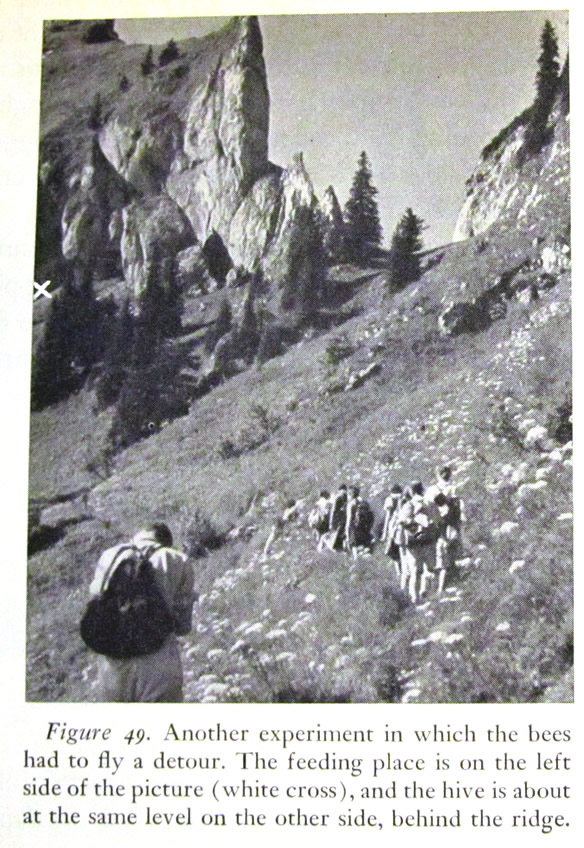

Here's a photograph of one of von Frisch's own laboratories, in his native Austria, shown in Figure 49 from his 1950 published lecture series Bees: Their Vision, Chemical Senses, and Language, Cornell University Press:

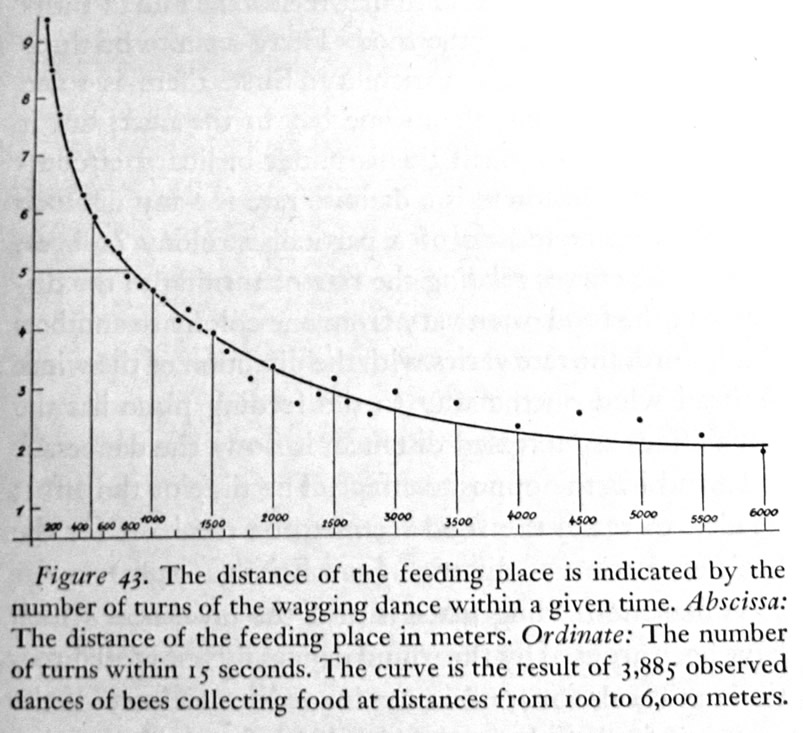

And here's an (summarized) example of the sort of data that he collected in these laboratories:

It's true that he didn't use "a massive library of video tapes of bees swarming around". This was partly because he did his research before video tapes were invented, and partly because video tapes wouldn't in any case have been an effective way to keep track of bee flights over thousands of meters of mountain meadows.

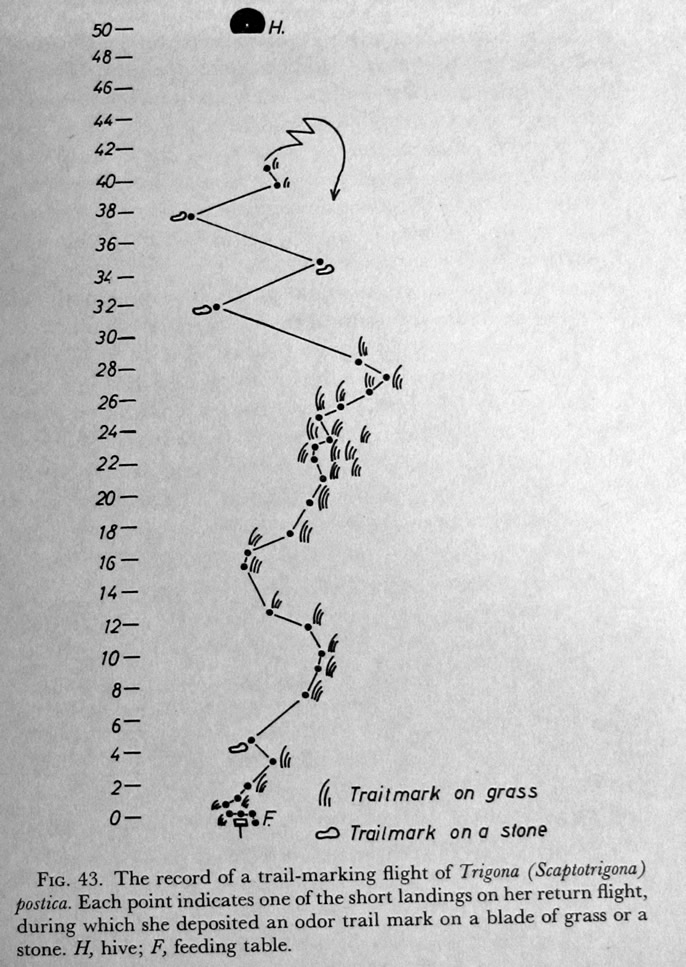

Here's an example of the sort of detailed track of bee flights in the wild that bee scientists made in the middle of the 20th century. This comes from Martin Lindauer, Communication Among Social Bees, Harvard University Press, 1961. Lindauer was von Frisch's student, and the monograph in question is the published version of the Prather Lectures in Biology, given at Harvard in 1959:

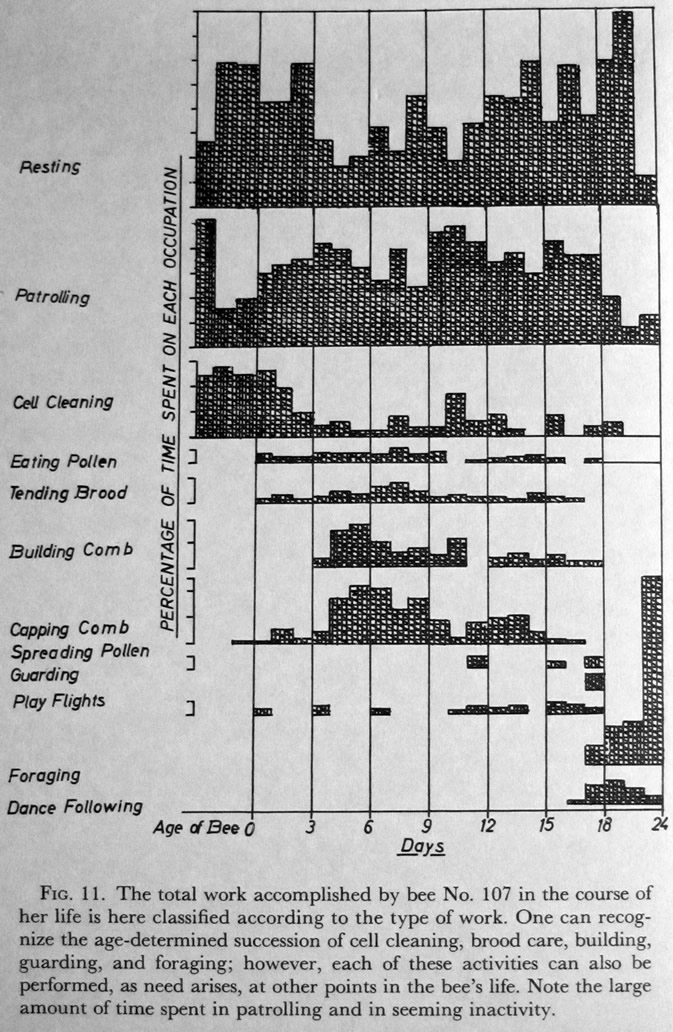

And here's Lindauer's detailed summary of the 25-day life of one particular bee — it's compiled from a series of day-by-day observation sheets that record in exquisite detail how much time the animal spent on each task, and when:

Observations like these were not compiled for their own sake, of course, but because bee scientists wanted to understand how bees navigate, how the division of labor in the hive is determined, and so on. For them, there was no radical divorce between "massive libraries" of observations and scientific insight — the evolving explanations motivated the observations, which both motivated and informed the explanations.

And to the extent that bee science had problems in the middle of the 20th century, it was lack of adequate data — their libraries of observations were not nearly massive enough. These painstakingly detailed observations of bee behavior, in settings ranging from completely natural through partly artificial to fully artificial, were simply too sparse to allow a wide enough range of theories to be evaluated and compared.

Even in 2003, Jennifer Fewell wrote ("Social Insect Networks", Science 301(5641):2867-1870) that

With these global attributes in place, how does information transfer within a social colony actually occur? Unfortunately, we do not yet have enough empirical data to answer this question well.

And she concludes:

What should be done next in the exploration of social groups as networks? We need to expand our models from elegant descriptions of single behaviors to incorporate the more complex dynamics of the group as a whole. We also need to test those models empirically on a wider range of social systems. Finally, to understand the evolutionary significance of network dynamics, we must explicitly measure their fitness effects on the social group. This interplay between network dynamics and selection is just beginning to be explored, and social insects have the potential to be on the leading edge.

A variety of new instrumentation techniques are starting to make it possible to gather more and better bee-science data more cheaply and conveniently. Thus according to J.R. Riley et al., "The flight paths of honeybees recruited by the waggle dance", Nature 2005:

In the ‘dance language’ of honeybees, the dancer generates a specific, coded message that describes the direction and distance from the hive of a new food source, and this message is displaced in both space and time from the dancer’s discovery of that source. Karl von Frisch concluded that bees ‘recruited’ by this dance used the information encoded in it to guide them directly to the remote food source, and this Nobel Prize-winning discovery revealed the most sophisticated example of non-primate communication that we know of. In spite of some initial scepticism, almost all biologists are now convinced that von Frisch was correct, but what has hitherto been lacking is a quantitative description of how effectively recruits translate the code in the dance into flight to their destinations. Using harmonic radar to record the actual flight paths of recruited bees, we now provide that description.

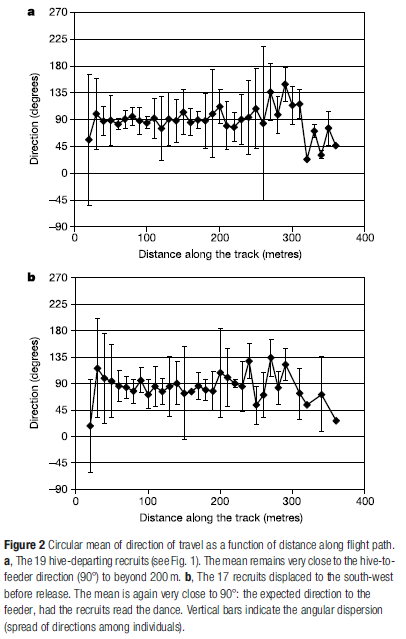

Here's a figure from that paper, derived from statistical analysis of the recorded flight-path data:

This is not yet "massive statistical analysis": there were only 17 foragers tracked, and they were treated entirely as individuals, except with respect to their interactions with the dancing foragers who recruited them. But this is mostly because the scientists had to glue a little radar transponder to every bee studied in this way. If bee scientists could easily get tracks of thousands or millions of foragers, co-indexed with the various interactions of these individuals within the hive, I strongly suspect that they'd be very happy indeed.

And it's exactly that kind of information — about human speech and language use — that today's "massive corpora" of diverse digital data streams offer to speech and language scientists. No matter how great and even well-deserved Noam Chomsky's celebrity might be, I doubt that his distaste for "massive statistical analysis" of the complexities of "things in their natural state" will be able to keep speech and language scientists from taking advantage of this opportunity.

[With some trepidation, I'm going to leave comments open. A warning in advance: unsupported and otherwise content-free expressions of opinion will be deleted, as will rant-like displays on any side of the various issues involved.]

Electric Dragon said,

June 4, 2011 @ 6:54 pm

The counter example that sprang immediately to mind was Kepler's laws of planetary motion, which he derived from Tycho Brahe's corpus of observations of planets. Of course Newton later came along and explained them with his law of gravitation, but that still had to be consistent with Kepler.

MattF said,

June 4, 2011 @ 7:20 pm

For what it's worth, Chomsky's characterization of what physicists do to model phenomena is naive. Physicists will happily use whatever tools come to hand– In particular, statistics is used to study dynamics of systems that are too complex to model in detail.

A particular example is Freeman Dyson's theory of large atomic nuclei– Dyson assumed that large nuclei were simply too complex to model in detail, so he modeled their Hamiltonians as random matrices. And then used information theory to model the correspondence between theory and experiment. And it worked! See here.

neuromusic said,

June 4, 2011 @ 7:34 pm

As mentioned by @ElectricDragon observations (including statistical descriptions of large datasets of observations) are precisely what any theory must be able to explain. This is where the "explanatory" power comes in… providing an account for how the statistical description came to be.

But a reduced, elegant explanatory model is only good if it fits the data.

Vicki said,

June 4, 2011 @ 10:22 pm

Thought experiments are fine things, and scientists try to check them. Galileo famously did a thought experiment about dropping iron blocks of different weights off the Leaning Tower of Pisa. It's a nice way of separating weight from air resistance (which is what slows falling leaves). But it's also an experiment that can be carried out (ideally not above a pedestrian plaza). If checking had shown that two one-pound iron balls fall at a different speed than one two-pound iron ball, we wouldn't be saying "never mind the data, it makes sense the other way." Modern physics is full of things that don't fit our intuition and common sense (I suspect this is at least part of why people are still trying to disprove the theory of relativity).

DCA said,

June 4, 2011 @ 11:22 pm

This brings to mind an aphorism attributed to Ernest Rutherford, "If your experiment needs statistics, you need a better experiment". But this can hardly apply to the sciences (for example, most of astronomy and the earth sciences [my own field]) in which experiment is impossible, and the complexities of the world as it is are unavoidable. Because some aspects of language can be studied by having people perform stylized tasks in the lab, I can see why it might be possible to convince yourself that you could do everything that way. But still, what an odd argument: physics envy strikes again.

Erik M. said,

June 5, 2011 @ 12:22 am

Critiques of Chomsky usually make me want to defend him. I'm grateful to find this thoughtful post that helps me understand his position as well as its blind spots and limitations.

John Cowan said,

June 5, 2011 @ 1:58 am

I think it's important to note that Chomsky has held this position for a very long time, probably (at least in his own head) since he was a young Turk rather than an older Ottoman. (He was certainly publicly making exactly the same analogy in a 1995 talk.) As a matter of academic generational politics, Chomsky's cohort was the one that cut linguistics loose from its origin in anthropology, so they needed to discredit linguistic fieldwork and the kind of theory that arose out of fieldwork, specifically the notion that mere observation can possibly lead anywhere. Outside North America, this plan didn't work so well.

[(myl) The argument against n-gram models based on sequence-probabilities famously dates to Syntactic Structures in 1957; and when I was a graduate student in the early 1970s, C more than once made an analogy between linguistic fieldwork and cataloguing the position of all the blades of grass in the lawn outside his office window (though as far as I know, this never made it into print). So his position on these points has been entirely consistent over time. What's different now? This sort of thing is a much larger fraction of what he has to say about language — roughly half, in the talk that I transcribed — and it's directed against a partly-new set of targets, including especially the opportunity for scientific use of computational methods applied to large bodies of linguistic data.]

Dominik Lukes said,

June 5, 2011 @ 3:22 am

The problem with Chomsky's emphasis on science is that he like most scientists doesn't really understand how science works (in the same way most English speakers don't understand how English works). In his hands, science is little more than a cargo cult. A perfect, immutable, found object reflecting the glory of its inventors. Scientific equals good and unscientific equals bad. And it is only the high priests who can tell which is which. Which is where the frustration of so many of his critics comes from. Arguing, with a Chomskean is like arguing with a deconstructionist, if you don't agree, you did not understand what they're saying. [Sorry, this may be a rant, so I'll stop here – some more "evidence" here.]

Aristotle Pagaltzis said,

June 5, 2011 @ 3:26 am

I must say, Mark, I can detect no restraint at all when Norvig writes “In this, Chomsky is in complete agreement with Bill O’Reilly.” In fact, on some level his essay seems to me an elaborately set up veil to use a satire of Chomsky as a plausible serious argument, with many readers possibly never quite realising what happened. On other levels the essay is in fact a serious argument, of course, but come on: one has to appreciate the cheek of a man to do that. Admire it, perhaps. I for one am greatly amused.

Paul said,

June 5, 2011 @ 4:12 am

Particle physics is basically gathering large statistical databases of collision results from particle accelerators. After a few billion collisions they examine the statistics of collision debries to discover anomalies that indicate unknown particles.

Chris Holdaway said,

June 5, 2011 @ 5:47 am

We recently had a seminar given by Suzanne Kemmer (Rice University) here in the linguistics dept. at Auckland University. The focus was on 'lexical blends', but since she was working within the framework of Cognitive Grammar, she talked a lot about the principles of cognitive linguistics as a big umbrella topic for what 'else' is going on. It was really interesting to be exposed to that sort of thing.

In my undergrad degree, we were almost exclusively taught P&P, since it's still part of the 'mainstream paradigm', but also a largely static and easily teachable theory in its obsolescence. There is a course on general functionalism, but its pretty scattered, and the only reason I've managed to get a taste of anything else is because one of our lecturers holds informal seminars on LFG in her own time, and my supervisor Yan Huang happens to be one of Steven Levinson's ex-students, so he's taught me a bit about neo-Gricean pragmatics.

Kemmer's talk prompted me to pick up Langacker (2008), which I'm working through slowly. I was particularly intrigued by the sections where he talks about how the field of linguistics is 'evolving' in the direction occupied by CG and other cognitive approaches. Though as a new graduate, I frequently get overwhelmed thinking about how many different ways of looking at things there are out there (let alone what's out there to look at itself).

Don't get me wrong, I found the work we did in P&P really interesting and challenging, and I think it taught me plenty. Hoping this doesn't get culled as a rant, probably wrote too much. Bleh.

Suzanne Kemmer said,

June 5, 2011 @ 6:32 am

"But increasingly, it seems to me, he has been elevating his personal distaste for the complexities of the real world into a systematic philosophy."

I haven't seen any change in NC's philosophy in this regard either (cf Cowan comment). He has always been enamored of theoretical physics as a field (and its idealized data–as though physicists didn't have to relate their idealized cases to the world ultimately); has never been interested in language use (in fact defined it out of linguistics by putting a firewall around competence and restricting data to grammaticality judgments); never was seriously interested in biology or its methodologies (or in evolution–until suddenly taking it up in the Hauser and Fitch collaboration); and has always been dismissive of statistical patterns in language and methodologies for discovering them. The latter distaste was already very clear in his negative review of Greenberg's Essays in Linguistics (Chomsky 1959, Word 15.202-218). Linguistics is a very interesting field, sociologically. With the loosening of these 50-year old constraints (which in my view have been part of a very systematic philosophy), it is getting to be interesting and exciting on the scientific side again.

Leonardo Boiko said,

June 5, 2011 @ 9:02 am

Yes, I have similar misgivings with Norvig’s article. I agree with the main thrust of his arguments, but he uses some underhanded strategies that bother me a lot, like the not-so-subtle connection at the end between Chomsky and Platonist belief in the transmigration of souls. Claiming Chomsky “is happy with a Mystical answer” (capital-M no less) is effectively an ad-hominen attack to our audience, making it seem like he believes in the supernatural. It’s pretty clear in the original text that Chomsky is only citing Platonist reincarnation as an interesting historical precursor. Chomsky does think the UG arise physically from the structure of the brain; it’s just that, as a rationalist, he isn’t interested in how exactly this happens. In fact he thinks unless we study the abstract structures first, we won’t even know what to look for in the brain. I happen to disagree, but is this approach that should be argued against, not a supposed “Mysticism”.

(I see that, since my first reading, Norvig has reworded much of the article, changing “a Mystic” to “perhaps a bit of a Mystic”. I respect his being open to criticism, but still see no need to discredit Chomsky in this way; there’s plenty of valid reasons to criticize his idea-school.)

[(myl) In the very first lecture that I ever heard Chomsky give, in the fall of 1965, he covered several chalkboards with examples and rules dealing with "affix hopping", but he also mentioned in passing that to date, the only empirically adequate theory of human learning was Plato's notion that learning is just remembering things you experienced in previous lives. Hilary Putnam got up and protested "Surely you aren't really proposing reincarnation as a scientific hypothesis!", and Noam responded, "It's a better hypothesis than anything psychologists have come up with since then".

I'm not suggesting that Noam believed or believes in reincarnation, but it's clear he likes to shock people by setting Plato up as superior to the past 150 years of psychological research. In fact, he's just as opposed to the reconstruction of Plato in terms of the idea that learning takes place in the genome — see his arguments with Pinker and others.]

DG said,

June 5, 2011 @ 9:43 am

I am a member of the post-Chomskian generation in computational linguistics: by the time I was in grad school, most of my professors abandoned his paradigm. Even my theoretical linguistics professor was a non-Chomskian in the sense that she didn't subscribe to Government and Binding. Nevertheless, I have quite a lot of respect for his work in the 60s. My biggest problem with him is that when he became the king of US linguistics he has imposed his philosophical views on everyone else. I wouldn't compare him to O'Reilly, I'll do worse: I'll compare him to Lysenko. Not in the sense of lack of academic integrity, but in the sense that his views were wrong and prevented progress in areas which he judged to be wrong based on his ideology. I think he has compensated for his advances in the 60s by contributing significantly to holding us back in the 70s and 80s.

In general, this makes me weary of anyone trying to prevent people from working on an area they judge useless: history has proven them wrong again and again. So nowadays I am sympathetic to people who don't work on statistical methods, maybe they'll have something to show for it some day:)

Tadeusz said,

June 5, 2011 @ 10:43 am

What was interesting and novel in the 1950's simply became an ideology, or even a religion. The course of Chomsky's views has been charted in numerous books, for example by PH Matthews, or Geoffrey Sampson. What is interesting is that neither Chomsky nor his followers bother to reply to any criticism, for example, there has been no response to the papers on falsehood of the doctrine of the poverty of the stimulus by Sampson and by Pullum or by Dabrowska (a Polish child cannot learn Polish, if we take Chomsky seriously), etc. And, if there has been, I would be very much interested to read it. What bothers me is how much Chomsky is still taken seriously.

Viktor said,

June 5, 2011 @ 11:22 am

I am no linguist, rather I am approximately a mathematician. And to me what Chomsky is after seems to be an inductive rather than deductive approach to his science. He wants to declaratively specify, he does not want to stochastically infer.

And as a mathematician this is how I go about my business, I define things the way I think that they ought to be, then I check their consistency against what others have said, I ponder their logical structure to see if I find it to be a tool I want to add to my toolbox. I may do a few mathematical proofs and presto, I have created a scientific artifact.

It does not seem to be a very practical way to approach linguistics, but to whatever extent a purely deductive framework proves to correspond to some manifest reality (as sometimes happens in physics) they tend to be brilliantly clear.

army1987 said,

June 5, 2011 @ 11:37 am

Galaxies were the first thing which sprang to my mind, before I even finished reading the post.

And unlike some physical experiments, I think “having people perform stylized tasks in the lab” has more rather than less complications than the situations language is most commonly used in. (Doesn't the difference between the results of the Wason selection task for colours and numbers and those for ages and drinks show that un-lifelike situations completely mess up with people's cognitive abilities?)

peterm said,

June 5, 2011 @ 11:40 am

From your earlier post: Norvig quoting Cass quoting Chomsky:

"Chomsky derided researchers in machine learning who use purely statistical methods to produce behavior that mimics something in the world, but who don't try to understand the meaning of that behavior. . . . "That's a notion of [scientific] success that's very novel. I don't know of anything like it in the history of science," said Chomsky."

Assuming he is quoted correctly, perhaps Chomsky's history is rusty. Newton's mathematical theory of gravitation was famously only predictive and not explanatory, as his friend Fatio de Duillier was the first to observe. Fatio attempted to develop an explanatory theory involving unseen particles, the so-called push theory of gravitation.

[(myl) Here's the corresponding passage transcribed from Noam's 10/2010 NELS lecture:

How all this applies to a particular piece of work seems to depend on what you think counts as "unanalyzed observations" and what counts as scientific insight into complex phenomena. The examples that he gives, such as video tapes of leaves falling or bees swarming, are calculated to seem simultaneously too complex to support a coherent and insightful analysis, and too trivial to deserve one. The strength of the argument, such as it is, depends on the listener accepting this disdainful attribution of complexity and triviality as applying to whatever other sort of evidence is to be discounted and avoided. The motion of the planets and the galaxies fails the sniff test on triviality, though there is certainly plenty of complexity there.

The animus against "prediction" is not easy to reconstruct logically, because I'm sure that C has a high opinion of Newton's success in generating complex kinematic observations from F = ma, inverse square gravitation and initial conditions — even though in some sense, as you observe, this can be seen as prediction without real causal explanation. I surmise that the difference has something to do with the degree of indirection and non-obviousness in the prediction: the move from f=ma to kinematic prediction seems (and is) more "explanatory" than (say) multiple regression does.

Anyhow, the sense of the quote that you cite seems to be accurate, whatever the details of the original wording might have been. ]

Rodger C said,

June 5, 2011 @ 12:32 pm

Norvig calling Chomsky a "Mystic" reminds me of Hockett, long ago, calling him a "neo-medievalist." That notorious review, which I read at age 11 or 12, was my introduction to Chomsky and (as negative reviews will do) fired my interest in him. Since then I've come to see that both Hockett and Norvig have their points.

Tadeusz said,

June 5, 2011 @ 12:48 pm

Viktor, this is exactly how this sort of grammar is supposed to describe languages ("describe" here is used in the non-technical sense, no relation to adequacy as used by Chomsky), which is quite natural given Chomsky's background and initial training in logic under Bar-Hillel (Sampson's description of the mythical book by Chomsky, "The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory" is quite fascinating, as he shows the mechanisms by which Chomsky was elected (wrong word, don't have a better one) to be THE linguist). Matthews, in turn, shows that in fact Chomsky made linguistics shift from evaluation of the fit of theoretical models to empirical data to evalutation of models themselves. And this is what Chomskyan linguists do. Hence there is no need to do anything with data.

Mark Etherton said,

June 5, 2011 @ 3:29 pm

Is Chomsky's characterisation of 'description' derived from Rutherford: "In science there is only physics; all the rest is stamp collecting"?

Chris Brew said,

June 5, 2011 @ 3:57 pm

The sniff test is a very personal thing. I like the astrophysics, but another good example might be epidemiology, where there is an obvious need to do analysis of complex and messy data, and to connect it to underlying causes. John Snow's "experimental" removal of the Broad Street pump handle during a cholera outbreak was motivated by modes of data collection (both informal interviews with members of the public and detailed mapping of cases) that Chomsky presumably doesn't enjoy, but did provide compelling evidence for a clean explanatory hypothesis about how cholera was being spread, which he might like.

sarang said,

June 5, 2011 @ 4:06 pm

Norvig's discussion of algorithmic modeling strongly reminds me of the discussions in the math community over computer-assisted proofs like the proof of the four-color theorem and Hales's proof of Kepler's conjecture. (See e.g. Doron Zeilberger, http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~zeilberg/Opinion47.html ) Unlike Zeilberger (and perhaps Norvig) I am uncomfortable with the notion of calling something an "explanation" when it can't be understood without the aid of a computer. There is a spectrum of OK-but-not-great reasons for simplicity preferences; at the "utilitarian" end of the spectrum, a good mental picture allows you to predict radically new phenomena, which would be a lot harder to do from a bunch of computer-generated output; at the other end, I am not sure that science would be intellectually interesting but for the principles. None of these arguments suggest that a simple answer can be found to any given question — so it might be misguided for Chomsky to insist that people look for simple theories in linguistics; perhaps a better phrasing is "people should be studying questions for which it is reasonable to hope that insightful answers exist."

David Eddyshaw said,

June 5, 2011 @ 5:25 pm

Much of medicine is *only* describable as scientific because it is based on proper clinical trials. These are certainly abstracted from the real messy world of disease, but are of course highly statistical and useful pretty much in proportion to their sheer size. The human body is far too complex for our current theoretical models to have the kind of predictive power you'd want to stake your life on.

peterm said,

June 5, 2011 @ 6:03 pm

If I may be permitted to comment on this statement in your earlier post:

"This is exactly the opposite of the general view among people working in related fields these days. Most of them subscribe to the belief that the "classical AI" of the 1960s and 1970s, based on the idea that intelligence is applied logic, led into an impassable swamp; and that practical progress resumed in the 1980s with a turn towards the idea that intelligence is applied statistics."

Working in AI, I would say this picture of AI's various intellectual turns is not quite complete. Rather, I think that every few years a new intellectual approach becomes technique-du-jour in AI (usually because it is successful at solving something previously overlooked or found to be difficult) – eg, search, AI Planning, logic programming, statistical pattern analysis, machine learning, bayesian networks, game theory. Nothing wrong with such variety of course, except that the proponents of each successive technique typically argue that AI is nothing more than the application of their particular technique, and disparage all other efforts.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 5, 2011 @ 9:33 pm

(Mark: Before I comment on Chomsky's misconception of science, I'd first like to ask what it is, exactly, that made you so reluctant to enable commenting on these two posts? Is it simply that Chomsky is a polarizing figure? But if that's the case, my impression of the commenters here is that LL and we are just not that sort of place.)

Anyway, when I first saw your first post and followed the links, my initial thought was exactly the same as peterm's: no doubt that Chomsky thinks of Newton as the paragon of science…and yet, as peterm pointed out, Newton's theory of gravity is remarkable in that it didn't bother to be anything but predictive. What is the "cause" of gravity for Newton? There isn't one. It just is and does what it does.

And the thing is…this was exactly the moment that science was truly born and it was for exactly this reason. I like to characterize it as learning to answer the 'how' question instead of the 'why' question. Natural philosophy prior to Newton was—even when more empirical—aggressively teleological. And the thing that is difficult for many people to understand is that the "why" of teleology is not very much different—or perhaps is no different at all—from the abstracted search for causation as explanation. After all, it's no accident that Aristotle is the giant of teleological natural philosophy and his explanation of the cosmos begins with the Prime Mover and ends with the Ultimate Purpose. The two are linked; they are in a deep sense the same intuitive attempt at comprehension, only from opposing perspectives. (My comment is already long, so I'll elide the related and necessary argument that the whole notion of causation is philosophically difficult and therefore suspect for exactly the same reasons as teleology is suspect. Put simply, we don't and can't really know what causation is. It's not as obviously elusive as is teleology, but when you approach it rigorously, it seems to recede away from you, always out of grasp.)

This perfectly human, almost certainly necessary (to cognition), desire to understand things from either/or the cause and the purpose of things has always been a huge stumbling block for natural philosophy—science—because, frankly, the universe mostly doesn't work that way. People certainly do—and, as this relates to the argument about AI that Chomsky is weighing in upon, I feel certain that we will never have a reductively successful AI until we manage to thoroughly understand the essential engine which is the Theory of Mind—which is to say, I think we will never have a reductively successful AI. But I'll leave that part of the topic alone for now.

Back to natural science, there are two strongly interrelated reasons why this intuition gets in the way of productive science. The first is, as I said, that especially with regard to teleology, the universe just doesn't work that way. But it's a problem with our desire to find causation as well because this pair of bookends—the cause and the purpose—strongly guides our intuition when we attempt to abstract models out of observation. Indeed, this is why Aristotle was such a poor empiricist. (Though, to be fair, what is really weird—and revealing—about Aristotle is that he both did an unusually large amount of observation and yet got much of it wrong, sometimes egregiously so.) Because, well: A) far too often our very strong beliefs about what is very likely or "must be" true with regard to our untrustworthy intuitions of cause and purpose spur us to abstract and model without even bothering with any observation at all; and, B) when we do go to the trouble of gathering data, we attempt to force it to fit to an abstraction that is misconceived at the outset because of our untrustworthy intuitions. And this most certainly does have bearing on the problems with Strong AI as anyone with any knowledge of its history surely knows. Computer Vision, anyone?

All this is why the Newton and the rest of the greats of the beginnings of modern science were so revolutionary and so successful: they learned to mistrust their intuition and just start to gather data and try to find abstract predictive models that worked as opposed to being, well, philosophers in the Classic sense.

Now, sure, the naive notion about the Scientific Method and its supposed observation without preconceptions is both simply false and couldn't work even if it were true. But its real value is that the focus on empiricism is a corrective against this deeply set intuitive desire for highly abstracted, perfectly emotionally satisfactory "explanations" for why things are the way they are. In reality, there is a cyclic relationship between observation and abstraction; they inform each other and neither should be seen as necessarily and inherently prior.

In any case, the previous commenters have mentioned numerous examples of contemporary science, including in physics, where this supposedly debased statistical focus is both necessary and extremely productive. What I find remarkable and disturbing is just how wrong Chomsky is about what science is and how it works; and how much his very ideological argument is more reminiscent of pre-scientific natural philosophy, rather than its exemplar as he believes it to be.

All that said, however, I certainly emotionally sympathize with Chomsky and Minsky and these older giants of cognition who had such high hopes for Strong AI. Of course cognition that cannot be expressed and understood as some sort of elegant, rigorous, and predictive theory is not very satisfying. The thing is, though, that the elegance of the sort that we admire so much in basic physics is almost certainly going to be rarely found elsewhere in nature. The universe is complex. Basic physics were the easy problems, with relatively few variables and, for that matter, a sort of observational theater that was practically within the purview of human comprehension. Not much else in the universe is like this. Why in the world would cognition, self-awareness, and language be the same sorts of problems as, say, Newton's Laws of Motion or even Einstein's Relativity? We really ought to begin preparing ourselves to accept that most of the universe will not be knowable in the way that we wish that we could know it. When we first accepted that this was true, that teleology was leading us badly astray, was when we first began to be truly successful in our natural philosophy. Giving up our qualitatively similar desire for simple elegance (which, frankly, is just as subjectively suspicious as teleology was) is almost certainly the necessary next step. Chomsky is certainly wrong about the philosophy of science, certainly wrong about the history of science, and not coincidentally he's probably wrong about AI.

I'll leave any judgments about what that implies about his view of linguistics to the linguists in the room.

LBHR said,

June 6, 2011 @ 1:56 am

@petern Chomsky has recently been recounting (correctly, as far as I can tell) the whole Newton explanation-vs.-prediction thing in recent talks, so I'm a bit puzzled by this as well. Perhaps he means that statistical patterns in language will always reduce to something Generativeoid?

Dan H said,

June 6, 2011 @ 7:32 am

Although I think Chomsky expresses himself badly here, and makes some rather silly generalisations about physics, I think it's worth pointing out that he does actually make a reasonable point (or at least, a point which is reasonable within one particular philosophy of scientific understanding).

It is certainly true that – as other posters have pointed out – Newton made no effort to "explain" gravitation, only to "describe" it, but that arguably represents a failure on Newton's part, not a categorical statement about the nature of science.

Norvig's essay – towards the end – seems to fall into the trap of assuming that "science asks how, religion asks why" but this simply isn't true. For any scientist who isn't a hard instrumentalist, part of the job of science is to find out what the world is *actually like*. People do actually want to know *why* gravity works and an inordinate amount of research in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has gone into answering exactly that question.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 6, 2011 @ 8:37 am

Well, yes. But this deep emotional insistence on "what" gravity really is, to understand it "truly" is a very good example of how that need can be as likely to lead one astray as it is to lead one to a reliably deeper understanding.

A friend of mine who is a more of a true scholar of Newton pointed out that I (and peterm) overstated the case and that Newton had to aver that he wasn't explaining the "why" of gravity for practical reasons external as well as internal; but that, even so, he did work from a strongly internalized intuitive theoretical framework that in the end hobbled him somewhat. My friend argues that Newton could have discovered relativity if he hadn't been so wedded to absolute space and time, which was already not as necessary an assumption in Newton's day as it had once been. (My friend has a particular interest in Newton's Optics and the aether.) And he concluded his email by pointing out that Newton modeled PM on Elements, after all.

And back to the 20th focus on gravity… I mean, really, I know that some of the posters here are physicists (IIRC), but aren't most of us aware of how even now we're not really any closer to this than we were with Newton? By that I mean to say this: we have no real, compelling evidence for a particle mediating gravity, though of course particle physicists are quite sure there must be one there in there somewhere (lack of evidence hand-waved away as being essentially undetectable, being the weakest force). Meanwhile, the vaunted General Relativity which does such a better job explaining how gravity behaves (predictive) has no explanation for the mechanism of that behavior…it's simply the altering of spacetime. I assert that this does no more to tell us what's "really" happening in the true causative sense which our intuition demands than did Kepler's Laws of Motion. The assumed graviton from the context of particle physics is more appealing to our intuition in this way.

But here's the first thing to note about this: the best theory of gravity we have is GR and yet it doesn't have the sort of reductive, intuitively satisfying "causal mechanism" that, say, gravitons do. But gravity in the context of particle physics and gravitons is nothing more than a notional supposition at present. It's not a theory. And, furthermore, back to GR, there's hardly anyone other than those working in a particular subfields of astrophysics who actually work with GR, or is, indeed, truly proficient with it.

So, you know, this vaunted 20th-21st Century effort to really understand gravity is not a compelling argument to me. Rather, I think it's a pretty good argument for my point that the real success always come from making the most elegant predictive models as possible and avoiding the constant temptation to describe what intuitively seems to us to be "how things are actually working".

Because our intuition about how things actually work is just not reliable.

Worse, much worse, it's not even clear that it even makes sense in the first place. I mean, what is causation? At any given point in time in the development of a scientific theory, we place causation right at our horizon of intuitive comprehension. And at that horizon is a sort of perpetual mystery, it's where the ultimate causal event happens, whatever that is. But it should be quite suggestive to people to realize that we just keep pushing that horizon farther away as we discover more intervening steps. Causation in the sense that we want to understand what causation truly is, what makes sense intuitively, is not a well-defined concept and is a piss-poor standard for making judgments about whether a theory is truly explanatory or not.

Having written all that, of course I'm not arguing that there's no difference whatsoever between, say, GR and throwing everything into some giant, monstrous computation pot, adding statistical voodoo, and coming up with some black box which is, apparently predictively reliable but incomprehensible. There's a good reason why we are not very comfortable with genetic algorithms which are apparently predictive for complex phenomena.

The point is that this is not the qualitative difference that most everyone, including Chomsky, seem to think that it is. It's quantitative. That is, it's not a difference in kind, it's a difference in extent. The qualitative distinction that our intuition insists must be there between statistical modeling and elegant theory says a lot more about human cognition, and its limits, than it says anything at all rigorous about the philosophy of science and epistemology.

More to the point, if criticisms such as Chomsky's against this indiscriminate and black-box statistical modeling are to be taken seriously, and produce real practical improvements in the relevant fields of investigation, then they need to be based upon a stronger comprehension of the epistemology behind science, what theories are, what explanations are, what causation is (and isn't, and couldn't be), and most especially with an awareness that the sort of naive adherence to asserting that there is some sort of "true" comprehension that is achieved only via the properly conceived theoretical model is a mindset that has proven to be far more counterproductive in the history of natural philosophy and modern science than it ever has proven to be productive. Thinking that we "truly" understand something is far more often an impediment to an improved practical understanding than it is enabling.

Or to put it a different way from a memorable lecture I saw Murray Gell-Mann give back in 1992 on creativity and physics: deeper comprehension is analagous to a deeper energy well such that creativity is the impetus that allows one to move from the relatively shallow theory well, upward to lesser comprehension, so as to eventually fall down into an even deeper theory well that, in the end, not only usually has better simple practical predictive power, it also feels like it's "more true". That it's a better theory. That it's exactly the sort of thing that Chomsky is advocating.

And the irony in this, in both Chomsky taking his position and in Gell-Mann giving that lecture, it is sort of a truism that the more one is inclined to being a powerfully creative and effective theorist, the more that, as one ages, one loses one's ability to utilize one's creativity to "let go" of the theory wells that one has discovered, feels one understands well, and has a sort of proprietary interest in defending. And I don't mean to imply strongly that it's about selfishness and propietary interest. What I mean to explicitly state is that this compulsion to really, really and truly, deeply understand something with beautiful and elegant theory is both a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing because one is more highly motivated, and likely better equipped, to discover these beautiful and deep wells. But, once discovered, that intuitive sense of comprehension has a powerful hold on one's mind; and, perhaps more to the point, particularly one's intuition.

This desire to intuitively understand things is deeply human, and we couldn't do science at all without it. But we ought to understand it for what it is: it's in us, it's subjective, it's not an independent fact of the external universe. Our own internal measurement of "comprehension" is not a measurement of how true something actually is in the external universe. It's possibly, perhaps likely, correlative to some functional utility, sure. But Einstein was wrong: GR didn't have to be true because it was so beautiful. God, I so totally relate to him with that quote. But he was still wrong. Beauty, elegance, our intuition about how something is or isn't truly explanatory…these aren't objective measurements. They're heuristics, at best. And the heuristics of statistical modeling is not, qualitatively, some sort of completely different and filthy beast.

Shmoo-El said,

June 6, 2011 @ 9:33 am

But increasingly, it seems to me, he has been elevating his personal distaste for the complexities of the real world into a systematic philosophy.

To me, that statement really resonates with Paul Berman's critique of Chomsky's over-arching philosophy in "Terror and Liberalism":

"Chomsky it must be remembered is a scientist in the specialized field of linguistics. He has always maintained that his political analyses and his linguistic theories are separate entities, without a logical bridge leading from one to the other. This seems to me not quite true. A single thought underlies the original version of Chomsky's linguistic theory, and it is this: Man's inner nature can be calculated according to a very small number of factors, which can be analyzed rationally. No shadow of the mysterious falls across the nature of man."

Dan H said,

June 6, 2011 @ 9:39 am

I assert that this does no more to tell us what's "really" happening in the true causative sense which our intuition demands than did Kepler's Laws of Motion.

I think we're talking at cross purposes here.

The point I was attempting to make was that it is not correct to assume that the *sole purpose* of scientific enquiry is to make predictions about the behaviour of systems. It isn't – if it was then as you point out yourself General Relativity is no more useful than Kepler, and barely more useful than Aristotle or for that matter than "tide comes in, tide goes out."

If the only purpose of science was to describe reality, particle physicists wouldn't have bothered to posit the existence of gravitons *at all* – the reason they have is because science *really does* care about mechanisms. Our current understanding of the universe requires all forces to be mediated by a particle and therfore either gravitons must *really exist* or else our entire understanding of the structure of the universe is wrong and, crucially, it is wrong *no matter how good its predictions are*.

Chomsky's criticism of statistical linguistics, insofar as I understand it (and I'm not a linguist) seems to be that it describes language without making any attempt to explain it. Chomsky is wrong to suggest that this is innately bad science – sometimes the correct answer really is "that's all there is" or "that isn't a useful question to ask". However it is an overcorrection to suggest that the role of science is to observe and never to explain the observation.

army1987 said,

June 6, 2011 @ 2:47 pm

Not directly relevant to Chomsky, but to some of the stuff which has been said on this thread: How comes no-one mentioned the “interpretations” of quantum mechanics? (“I think I can safely say nobody understand quantum mechanics” — R. Feynman)

Keith M Ellis said,

June 6, 2011 @ 3:05 pm

Well, yeah, that's a good example, too, as far as it goes.

I find it extremely interesting that for the first twenty or so years of QM, physicists were deeply interested in what it all meant. And the thing is, no one really resolved these questions to everyone's satisfaction. Instead, what happened is that reputable physicists stopped worrying about it.

About ten years ago I came across a particle physicist who listed on his website and CV and such that he was interested in the "philosophical implications of QM". I wrote him out of curiosity and asked him how this interest of his goes over among his peers. (He had a tenured research position at a large institution.) He wrote me back, in good humor, and said that because he does other more conventional work, his colleagues tolerate his eccentricity in being interested in issues that are now considered unfashionable and somewhat disreputable.

But, well, you know. I find the topic as fascinating and infuriating as anyone else does (as a layperson, that is). But it sort of also demonstrates my point. We haven't really needed to get to the bottom of what QM "really" means to greatly expand it and refine it; and QCD is just about as successful a physical theory as has ever existed. It turns out that neither do we need to get to the bottom of these puzzling and weird things about it in the sense of "comprehension"; but that, indeed, our deep desire to do so ended up being a counterproductive diversion. Nowadays, physicists say that what is real about it, what is true, is the math itself, not what the math "means". I somehow suspect that Chomsky would, or does, find that very disagreeable. I'm not entirely comfortable with it myself. But then, I also don't expect science to satisfy my aesthetics and emotional need for comprehension and simplicity. Why in the world should it?

Incidentally, although you probably know this, it was Feynman and Gell-Mann who "finished" QM with their contributions to QCD. It's not trivial when Feynman says that nobody understood quantum mechanics.

On the other hand, both those guys are/were so much smarter than almost everyone else that they were able to know they didn't understand things, and that no one else did, when everyone else thought otherwise. It takes being pretty damn smart to know that one understands very little about the things one ostensibly knows a great deal about.

I'm quite obviously, and regrettably, not nearly so smart. Alas.

bianca steele said,

June 6, 2011 @ 3:55 pm

Isn't part of the reason classical mechanics wasn't worked out using statistics that statistics was worked out in part by considering what happens when repeating the experiments of classical mechanics large numbers of times? "We don't work out the positions of comets by making lots of observations and doing statistical analyses of them," for example, rings a little odd.

Chomsky seems not only to insist that scientists need theory in addition to just making experiments, he seems to insist that only a specific kind of theory could possibly be a good one, and that we can know that before looking to see what the experiments show. (So, then, he assumes certain kinds of research can never get past what may not really be problems, or may actually currently be problems, just because they are those kinds of research: algorithmic work being one of those (not as directly addressed by Norvig, at least in this sense), statistics being another.) Personally, this is what bothers me: the going beyond saying "grammar matters, linguists should know about subjects and predicates and all that mental structure, or they will get nowhere describing language," to a rather different kind of linguistics theory. It seems a little bit more drastic than just an "overcorrection."

Dan H said,

June 7, 2011 @ 4:32 am

He wrote me back, in good humor, and said that because he does other more conventional work, his colleagues tolerate his eccentricity in being interested in issues that are now considered unfashionable and somewhat disreputable.

Umm … I really don't think that the philosophical implications of elementary physics are considered "unfashionable and somewhat disreputable". Oxford University offers joint honours degrees in Physics and Philosophy, and teaches the Philosophy of QM in the third year:

http://www.ox.ac.uk/admissions/undergraduate_courses/courses/physics_and_philosophy/physics_and.html

Pretty good for a "disreputable" field.

Dan H said,

June 7, 2011 @ 6:19 am

Personally, this is what bothers me: the going beyond saying "grammar matters, linguists should know about subjects and predicates and all that mental structure, or they will get nowhere describing language," to a rather different kind of linguistics theory. It seems a little bit more drastic than just an "overcorrection."

Oh I absolutely think Chomsky is wrong here, what I was calling "overcorrection" was the suggestion or implication I was picking up from a lot of people that it is actively *undesirable* for science to attempt to work out the mechanisms behind phenomena. People seemed to be going from "the collection and analysis of data is a legitimate and indeed necessary component of scientific study" to "the collection and analysis of data is the only valid component of scientific study and everything else is superstition, mysticism, and an unscientific yearning for answers" – as a couple of other commenters have pointed out, Norvig's essay characterises Chomsky's belief in a physiological basis for language as akin to belief in God.

Where I think Chomsky is right is that *if* you believe that language *really does* have an underlying set of principles which stem from human physiology, and which can be investigated by artificially constructed experiments, then those underlying principles are worth investigating and are (arguably) more worth investigating than the actual phenomena of language.

Where I think he is wrong is in failing to realise that *not* believing that language is based on a set of underlying principles which stem inevitably from human physiology is *also* a valid scientific position, and that from that position statistical analysis of language phenomena is far more valid than searching for an underlying structure which may not actually exist.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 7, 2011 @ 6:44 am

I hardly see how an undergraduate degree program is a very convincing counterargument, even from Oxford. Do you know any working particle physicists? I do, several of them. And you have the (second-hand, admittedly, but you didn't question my veracity) attestation of a working particle physicist that the philosophy of QM is not well-regarded.

Perhaps you understood "disreputable and unfashionable" to be nomarlized to the broader cultural context. In that regard, yes, your Oxford example shows that this isn't, you know, ESP studies or anything at all like that.

But within the reputational community of working PhD particle physicists? No, it's not well-regarded. It's sort of embarrassing. Something that someone would do who can't be bothered to do actual meaningful work, or get funding, or has been denied tenure and prefers to teach, or is in their twilight years and allowed to indulge themselves in idle curiosity. Every discipline has interests like these. They are the sorts of things that ambitious young scientists avoid like the plague.

If you don't understand this context, I don't understand why you're bothering to argue with me about it.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 7, 2011 @ 6:58 am

But I certainly haven't written that, either implicitly or explicitly. You're wrongly inferring it. And you're doing so because, I think, you have a naive view about "mechanisms behind phenomena", how they are understood, whether they can be understood, what it means to claim that one has identified such things, how this relates to prediction, and, most importantly, how this relates to the interplay being model-building and data-gathering.

It's interesting and provocative to me how the naive materialist realism of most scientists functions, psychologically and subculturally, very much like a variety of idealism. And more to the point, I think for these reasons it is vulnerable to the same weaknesses of idealism, vulnerable to very similar critiques to those of idealism, vulnerable to the same debilitating and prejudicial habits of thought of idealism.

It is not unreasonable (though it is arguable intemperate) for Norvick to criticize Chomsky as a sort of platonist because, really, Chomsky is basically saying that we shouldn't be fooled by carefully observing all those various shadows on the cave wall, we need to be smarter and enlightened enough to turn around, look outside, and see the "truth" of things…because that's what Real Science™ truly is.

bianca steele said,

June 7, 2011 @ 10:52 am

A couple of comments re. @Keith:

One: I think there is certainly a difference between Platonism, which doesn't actually ask us to look outside, and respect for ideas. The commenters who referred to medievalism in this respect, I assumed, intended to indicate that Platonism is generally a poor fit for modern science (the kind that gave us modern physics–to my knowledge the physicists haven't rejected this, whether as insufficiently "scientific" or for any other reason). Two: There is also a difference between Platonism in terms of one's theories' being intuited or whatever, Platonically, and Platonism in terms of having a Platonic (or similar) theory of human psychology–Chomsky may well risk Platonism in both senses. It's even more than doubly confusing IMVHO because there seems to be something "structuralist" in the Levi-Strauss sense in Chomsky's theories, if I understand them correctly, but he uses "structure" in an entirely different sense that isn't especially easy to match up with the more usual "structuralist" sense.

So, it would be doubly a mistake–IMVVHO–to confuse theory with theology, as Dave H suggests, describing those with belief in a theory as having belief in God, or in a god.

It may be a perfectly satisfactory field of research in itself, but if Mark Liberman was suggesting in his initial post that it crowds out other kinds of research, I think this is plausible.

Dan H said,

June 7, 2011 @ 11:14 am

But I certainly haven't written that, either implicitly or explicitly. You're wrongly inferring it. And you're doing so because, I think, you have a naive view about "mechanisms behind phenomena", how they are understood, whether they can be understood, what it means to claim that one has identified such things, how this relates to prediction, and, most importantly, how this relates to the interplay being model-building and data-gathering.

As I say, I think we're both talking at cross purposes.

I absolutely agree that science is not in the business of providing Ultimate Truths, certainly you can never get to a point where there isn't one more "why" or one more "how" or one more "what the hell is that all about". I also absolutely get that distiguishing between an effective, predictive mathematical model and "reality" is nonsensical.

What I think I disagree with in what I think you're saying is that I *do* think an important part of scientific enquiry is finding out actual facts about the nature of the world. Thinking about it, I don't think you were ever denying that this was the case, just sressing that (if I'm reading you right) it's important to understand that these facts often take the form of a complex mathematical model.

The reason I think Chomsky is being unfairly characterised here is that I don't think he's failing to understand the nature of scientific enquiry or for that matter the value of statistics. I think he's just engaging in the same kind of scientific dickwaving as when Rutherford declared all sciences other than physics to be "stamp collecting".

As I read it, Chomsky's criticism of statistical linguistics isn't grounded in a genuine inability to believe that reality can be accurately represented by a statistical model, but in a dissatisfaction with a style of linguistics which doesn't answer the questions he is personally interested in.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 7, 2011 @ 4:07 pm

Dan H, I really like your comment and agree with all of it. I think we probably do agree with each other in almost every respect. And, yeah, I think your paraphrase of my argument vis a vis "actual facts about the world" is pretty much just right.

However, I do think perhaps you're being a bit generous to Chomsky. Or would that be ungenerous? You're reading him as engaging in some hyperbole that is aimed at defending his own intellectual turf. That's both generous and ungenerous because you're giving the benefit of the doubt with regard to his actual argument (that he doesn't mean exactly what he's saying; what he means is more reasonable that what he's literally arguing), while this casts his motivations in a pretty unflattering light.

I'm more inclined to believe that he mostly means what he's saying and that it's because he is, first and foremost, a grand theorist and thus believes in his heart of hearts that "true" science is grand theories and everything else is footnotes or a waste of time.

Dan H said,

June 8, 2011 @ 5:45 am

I see where you're coming from, and again I think we're sort of on the same page anyway. I think he's engaging in the same kind of hyperbole that physicists engage in when they say that Chemistry is "just applied physics" (as I think the original post points out, Chomsky's analogies here are clearly chosen for their rhetorical impact – to give the maximum impression of both frivolity and incomprehensibility).

I actually think Chemistry/Physics is quite a good analogy for the situation here (although I say that as somebody whose knowledge of physics far outstrips his knowledge of Chemistry, which itself far outstrips his knowledge of linguistics). A great deal of the study of Chemistry can proceed purely from the observation of chemical reactions (and indeed it did for most of history) but there is a lot of chemistry which relies very strongly on understanding various models of atomic structure (from the basic use of the Bohr model in descriptions of bonding to the complex applications of quantum mechanics in physical chemistry). I *think* that Chomsky sees statistical linguists as being like a bunch of chemists refusing to think about the structure of the atom, content to simply compile endless catalogues of chemical reactions rather than working on a theory which might prove more powerful and more predictive.

Unfortunately the way he expresses himself makes him sound more like a physicist insisting that people should give up the study of chemistry altogether, because all chemical reactions stem from the underlying principles of atomic physics, which is nonsense.

Keith M Ellis said,

June 8, 2011 @ 10:20 am

But…um…

The Bohr model, which people even today think describes the actual physical configuration of the atom is at best misleading and at worst completely wrong. It's a nice idea, and has been (and is) a helpful mental model for understanding certain things, but subsequent progress in physics shows it to be hopelessly naive and, per my many arguments above, often deeply misleading to those scientists who think it describes what an atom "really" looks like, if only we could see one with our own eyes. The constraints placed upon our intuitions about what happens in and between atoms because of that model cause us to assume some things aren't possible which are, and some things are possible which aren't.

QM has a much, much better description of the atom except that, well, it's not really a description at all in the sense that the Bohr model is. It doesn't satisfy our intuitional desires at all, that's why people constantly argue about the philosophy of QM and why actual particle physicists have taken the position that there is no there there except for the math itself.

Yes, the math itself is, as you put it, "[facts] in the form of a complex mathematical model", but personally I do think that maybe you're missing my point that this is really a quantitative argument when many of the people involved think it is qualitative. Chomsky, I think, as well as many others would want to say that the complex math of QM which so well described what is happening and makes up, without a doubt, a physical theory is a qualitatively different thing that a complex statistical model such as what he's deriding. But I think that were we to talk to a particle physicist who is both competent in QM and the relevant experimentalism, as well as being pretty savvy about philosophy of science and such, he/she would tell you that while there's obviously something quite different between the two, there arguably isn't some bright line between them, a qualitative discontinuity, that separates them when placed upon a continuous line from one extreme to the other. I'm putting words in someone's mouth and according myself an authority I've not earned, to be sure, but I really think this is true. I think this is really a quantitative difference, that there isn't some bright line distinguishing the two, and it's only the cumulative quantitative difference that causes us to feel quite strongly that they are qualitatively different. And I tend to think that is real; that is, enough quantitative distinction and you get something that is defensibly a qualitative distinction.

But the point is that this is a pretty good example, because particle physicists do, in fact, use sophisticated statistical models, both theoretically and experimentally. Both build these statistical models from the gathering of statistical data. This is all bounced off a more abstract theory, of course, but that's sort of the point. Chomsky is right to assert that we want to, and should, try to find that abstract theory to which to resolve the "meaning" of our statistical data. He's wrong, though, to the degree to which he seems to argue that the gathering of that data is a waste of time. It emphatically is not.

Brett said,

June 8, 2011 @ 1:41 pm

As a physicist who matches the description you just gave, I would pretty much agree with the sentiment that there is a smooth spectrum between the two theoretical extremes you have described. Yet while it may be common, I'm pretty sure this view is not universal in the relevant physics community.

Dan Hemmens said,

June 8, 2011 @ 4:56 pm

Again, I think we mostly agree – the reason I mentioned the Bohr model was because I think the different levels at which chemical reactions can be understood highlight the fact that different levels and types of model are all useful (the Bohr model might be misleading, but it was actually a key stage in the development of our understanding of atomic physics), and I certainly agree that there is no clear difference of type between the mathematical formulation of Quantum Mechanics and the mathematical formulation of statistical linguistics (although I suspect there are a lot of quite important technical differences and as I say statistical linguistics is something I know precisely nothing about).

John Cowan said,

June 8, 2011 @ 5:55 pm

Wikipedia says that tremata in Byzantine Greek are the spots on dice , so probably the name trema for the ¨ character refers to its shape, and can be used whether it notates diaeresis, umlaut, centralization (as in IPA) or something else.

army1987 said,

June 9, 2011 @ 12:33 pm

Anyway, many books about quantum mechanics do have a short chapter or appendix about interpretations, but IMO such an amount of bollocks has been said (mostly by non-physicists) about such topics (or about special relativity, for that matter; “Hopi time” anyone?) that we're tired of discussing interpretations of QM *at all*.

This week in cultural evolution June 12, 2011 - simon.net.nz said,

June 12, 2011 @ 1:02 pm

[…] so a group of French and Greek geologists and archaeologists decided to put it to the test.Language Log » Straw men and Bee ScienceIf you followed my advice (in "Norvig channels Shannon contra Chomsky", 5/31/2011) and […]

Chomping at Chomsky « Aliens in This World said,

June 15, 2011 @ 7:42 am

[…] are many reasons to resent Chomsky's effect on the field of linguistics. But here's an essay on one of the most basic problems with his approach — he likes to call his approach science, but it's really really […]

ke said,

June 15, 2011 @ 10:35 am

I think the theme of this debate appears in a more general and radical form in Chris Anderson’s essay “The End of Theory”:

http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/anderson08/anderson08_index.html

Olaf Koeneman said,

August 3, 2011 @ 10:36 am

@Tadeusz:

"What is interesting is that neither Chomsky nor his followers bother to reply to any criticism, for example, there has been no response to the papers on falsehood of the doctrine of the poverty of the stimulus by Sampson and by Pullum or by Dabrowska"

To give you one example:

http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~ycharles/papers/tlr-final.pdf

I haven't seen a response to this…

mark said,

April 8, 2013 @ 2:41 am

And now: a new species of bee is named after the great philosopher: Megachile chomskyi. See here.