Real tone

« previous post | next post »

In 'Tones for real", 2/5/2018, John McWhorter expresses his frustration as an American learner of Chinese: "How much must I attend to the damned tones in a sentence, as opposed to in citation, to really speak this language?"

As John very well knows (when he's not frustrated by the difficulties of learning a new language), his question has the same answer as the analogous question "How much must I attend to the damned consonants and vowels in a sentence, as opposed to in citation, to really speak this language?" Fluent native speakers almost never use standard citation forms in fluent speech — sometimes the fluent versions are reduced or assimilated or dissimilated versions of the citation forms, and something they're just variably different. This is partly because informal speech is variably non-standard, but mostly because of the complex effects of linguistic and communicative contexts on the phonetic realization of phonological categories.

Unfortunately for language learners, these complex effects (though in some sense "natural") are different in different languages and dialects/varieties, so you can't just use your normal phonetic habits and expect the results to sound right. And we can use John's own pronunciation of English to illustrate some of these contextual effects.

In John's 2/6/2018 podcast with Glen Loury, "Being Black in 2018", I probed randomly near the start to find one of John's turns, and pulled out the opening phrase:

Well you know you're- you're not wrong, and you know what

Let's skip the obvious things, like [jɪˈnoʊ] for "you know" and [jɚ] for "you're", and ask about the seventh and eighth syllables, "wrong and". If we listen to them out of context, they sound like [ˈrɔŋ.in] "wrongeen" (or maybe "wrongy"?):

Why? Well, "and" becomes a reduced vowel plus [n], and the vowel assimilates across the nasal to the initial high front glide of the following "you".

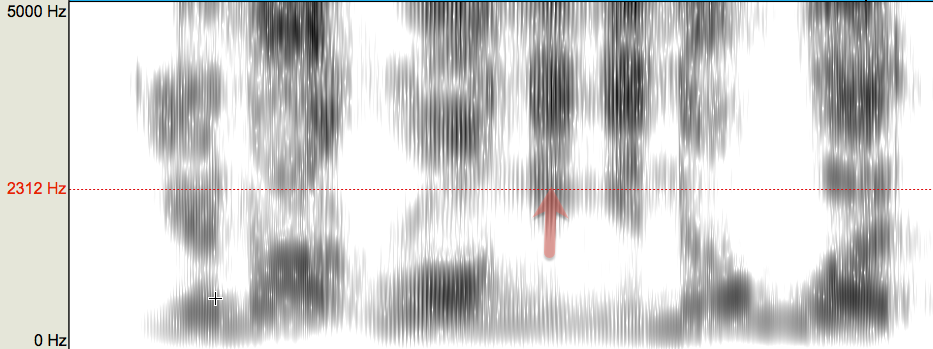

And the result really is phonetically a high front vowel — look at that F2:

Of course this doesn't mean that it's always OK to pronounce "and" as "een". It depends — and knowing what things like this depend on is one of the hardest parts of learning to speak fluently and idiomatically in English or in any other language. (This is frustrating for learners, but it keeps phoneticians in business…)

We could go into John's next few phrases and find similar examples of extreme contextual modulation of pronunciation — including plenty that involve only parts of content words — but I'll leave it there for now. Rest assured, though, that we'd find additional evidence in every phrase that vowels and consonants in fluent speech are not the same as vowels and consonants in citation forms.

So what about the Chinese syllable that was frustrating John, zai4 在?

To get an idea about how Chinese speakers deal with zai4, let's look in a dataset that Neville Ryant, Jiahong Yuan and I put together a few years ago, "Mandarin Chinese Phonetic Segmentation and Tone". It consists of 7,849 cleanly-enunciated phrases from various Mandarin Broadcast News sources, divided (for purposes of machine-learning evalutation) into 300 test and 7,549 training examples. Obviously this is formal, standard, carefully-pronounced speech — but it's still language used to communicate, not "citation forms".

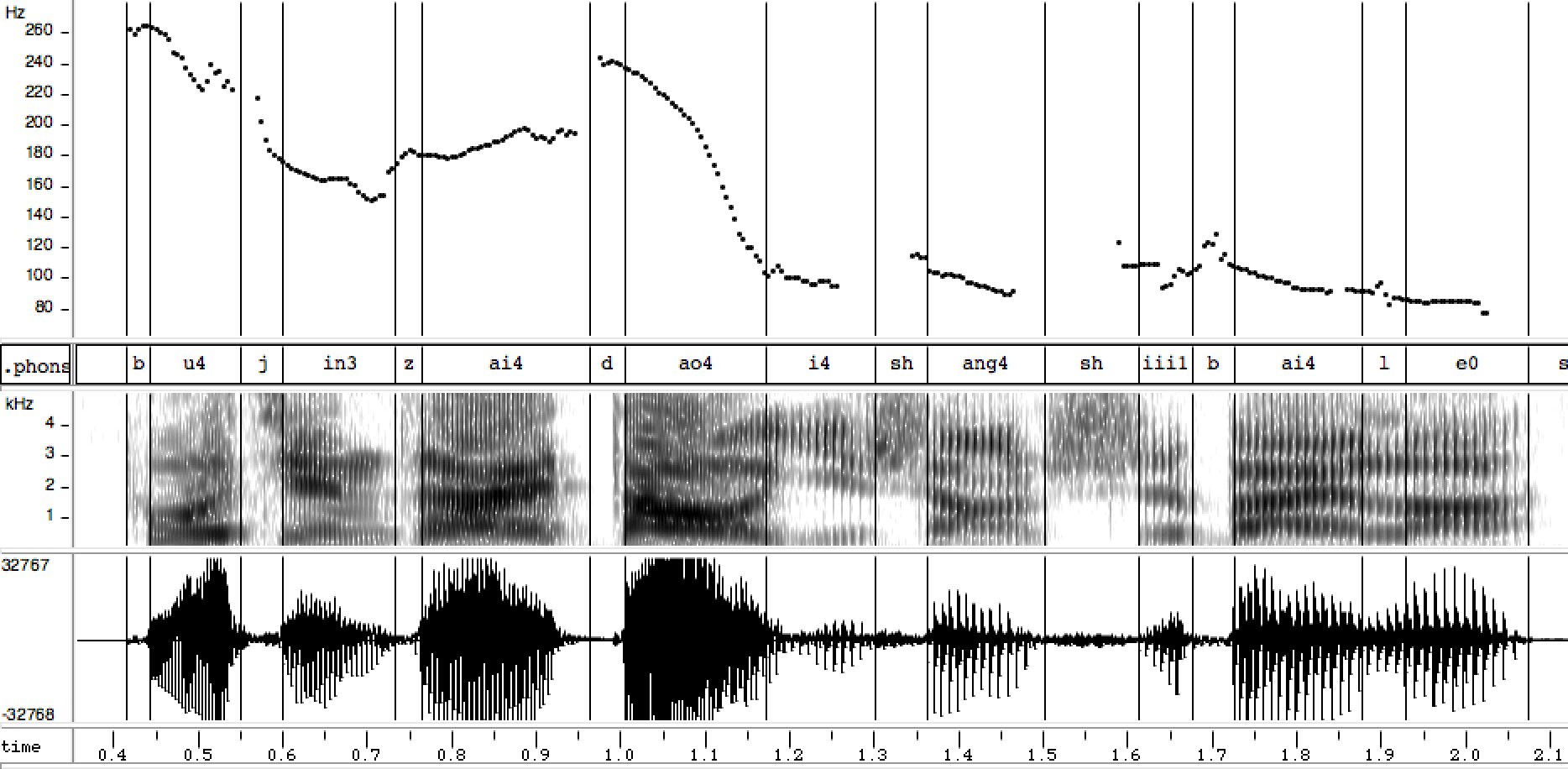

在 is a common-enough morpheme that it occurs 56 times in the 300 test sentences. The first one (in collating order of file names) is in the file test/chj000019 — which happens to include not only zai4, but five other tone 4 syllables. And as you can see, their realization in terms of pitch contours is quite diverse:

不仅 在 道义 上 失败 了

bu4 jin3 zai4 dao4 yi4 shang4 shi1 bai4 le0

In fact, weirdly enough, this zai4 is actually mid rising, although the canonical tone 4 pattern is high falling. Does this mean that it's always OK to pronounce zai4 as mid rising? Even if this example is not mislabelled, the answer is "obviously not — it depends". Presumably what it depends on in this case is that zai4 falls between jin3 (which ends low) and dao4 (which starts high), and is prosodically weak due to the syntax and semantics of the phrase, to the point that its intrinsic pitch contour is essentially taken over by the contributions of the adjacent syllables — just as the vowel quality of John's and was determined by its context.

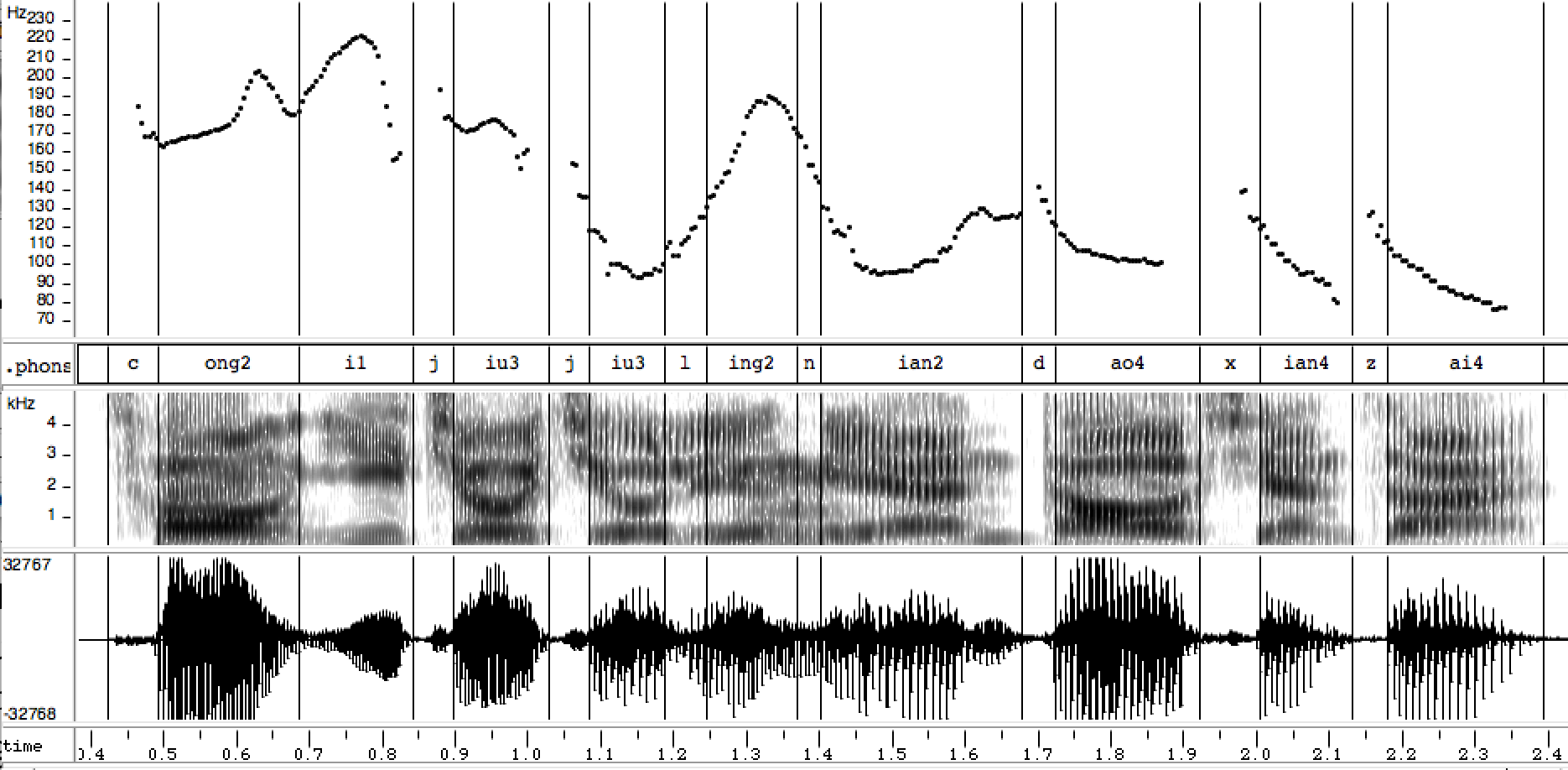

The next zai4 file has four tone 4 syllables at the end, closing with zai4:

从 一九九零年 到 现在

cong2 i1 jui3 jiu3 ling2 nian2 dao4 xian4 zai4

This time zai4 is actually falling, but just not so much, presumably because it's in a region of the phrase where the pitch range is compressed — a property that it shares with the previous three syllables.

If we went on to look at the other 54 zai4 examples in this dataset's 300 test sentences, we'd see additional ways in which tone in fluent sentences is not tone in citation forms.

Of course, there are other features besides f0 that are involved in the perception and production of Mandarin tones, as discussed in the papers connected with that published dataset:

Neville Ryant, Jiahong Yuan, and Mark Liberman, "Mandarin tone classification without pitch tracking", ICASSP 2014

Neville Ryant , Malcolm Slaney , Mark Liberman , Elizabeth Shriberg , and Jiahong Yuan, "Highly Accurate Mandarin Tone Classification In The Absence of Pitch Information", Speech Prosody 2014

Or see this sideset from a 2015 presentation about those results — Tone Without Pitch.

For some discussion of factors influencing Mandarin tone 4 realization in tone4+tone4 words, see Wei Lai, Jiahong Yuan, and Mark Liberman, "Prosodic Strength Intrinsic to Lexical Items: A Corpus Study of Tone Reduction in Tone4+Tone4 Words in Mandarin Chinese", ISCSLP 2016.

Antariksh said,

February 7, 2018 @ 1:19 pm

I think a common source of frustration among language learners (whether of English or Mandarin or really any language) is that there are often a lot of differences between what language teachers say vs what they do. This is particularly true when the teacher is not trained in linguistics.

Teachers often insist on what is 'theoretically' right (in this case, the canonical citation forms), while not actually talking that way themselves (because, well, nobody does). When you combine that with excessive deference to the written form of the language, which is common in most language classes, it is natural for students to be confused and frustrated.

Daniel Tse said,

February 7, 2018 @ 1:59 pm

Minor typo 'jui3' for 'jiu3' in the article.

[(myl) Thanks! Fixed now.]

Chris Button said,

February 7, 2018 @ 3:07 pm

@ Mark Liberman

While many posters on the previous thread (including me) pointed out the effect of the surrounding environment on the actual realisation of tones, I think an alternative analysis which ties into your "prosodically weak" comment might also apply to the relatively extreme case here.

I would suggest that "zai" might be an unstressed syllable here that is then subject like any unstressed syllable to the effects of the tone that precedes it (which is why toneless syllables do actually bear a sort of tone). As such, what is happening is that the rising portion of "jin" is actually being transferred onto "zai" (whose tone 4 has been rendered relatively inconsequential) to give it a rather different realization from its standard form. In short, "zai" is not so much warping its tone 4 under the influence of tone 3 in "jin" but rather it is simply waiting as a relatively blank slate for its input from its surroundings (the following tone on "dao" then simply adds to the effect).

[(myl) Indeed, this preposition(-like?) usage of zai4 might be a case where a morpheme becomes "tone 5", i.e. no lexical tone at all, and just picks up its pitch contour from the context. We'd need to look at a larger range of cases to distinguish "deletion" from "reduction", which is as tricky for tones as it is for consonants and vowels.]

Michael Watts said,

February 7, 2018 @ 3:07 pm

The fact that 仅 is tone 3, the "dipping tone", which in citation form is a fall followed by a rise, probably helps a lot as compared to a context where the syllable before 在 is tone 4. Nobody has time in fluent speech to do the full fall-rise sequence for a tone 3, but a 3-0 (dipping-neutral) tone sequence seems to regularly transform into a 3-1 (dipping-high), with the reduced syllable providing space for the dipping tone to realize its full self. e.g. 好好 hǎohāo, 奶奶 nǎināi.

For non-Chinese speaking commenters, the 在 in the first sentence is a preposition roughly corresponding to the "of" in "it's not just a failure of morality", which does seem like a pretty good candidate for reduction. The second one is not an independent word, or even a clitic, at all; it is the second syllable of the word "now". ("From 1990 to now".)

This comment's view of the effect of dipping tones on following syllables is based mainly off of dictionary entries and other people's past comments on LL, not personal experience.

Michael Watts said,

February 7, 2018 @ 3:09 pm

Ah, scooped by Chris Button by all of zero minutes.

Philip Taylor said,

February 7, 2018 @ 4:10 pm

Interesting article, and singularly apposite as I submitted this review earlier today (the book must remain nameless) — "To be honest, I didn't read beyond page one. To try to convey a tonal language through the medium of a toneless transcription into what appears to be a nonce (very) broad romanization is misguided at best and at worse completely pointless. Please, anyone hoping to learn enough spoken Chinese to get by in China, get a well-written primer that emphasises the importance of tone and uses the standard modern pinyin transliteration. This book will simply make you a laughing-stock in China."

Jason said,

February 7, 2018 @ 4:19 pm

You wrote, “This time zai4 is actually falling, but just not so much, presumably because it's in a region of the phrase where the pitch range is compressed.” However, there appears to be a difference between 在 as a preposition or (stand alone) aspect marker and whether it is the second constituent of a compound (e.g. 现在 xianzai “now,” or the aspect marker 正在 zhengzai ‘progressive aspect’). Northern Mandarin dialects weaken the second constituent of compounds, regardless of the position in the phrase. But that could be easily tested.

[(myl) This is certainly relevant, but note that in this case the first syllable of 现在 xian4 zai4 is not very different from the second syllable in terms of the range of f0 values it spans — both falls are relatively small.]

Jason said,

February 7, 2018 @ 4:20 pm

BTW It’s this kind of article that makes me a remorseless Liberman junkie…

Andrew Usher said,

February 7, 2018 @ 7:06 pm

I note that the passage chosen of John McWhorter's speech is perhaps not completely suited for this message: he enunciates all the vowels and consonants (and that doesn't sound strange here), but only reduces some vowels like every English speaker. The only one of note is the one you mention, but given that English schwa (at least in unstressed closed syllables) is pretty much unspecified for place, the chance of confusion is nil and it can hardly be called 'sloppy' like many connected-speech processes.

{(myl) You're right. But it would have been unfair in another way if I'd chosen some more informal, vernacular, passage. Of course I wanted to use John's own speech as a source of examples, and he's in general a careful speaker. But that's OK, because the point is that even carefully-articulated formal speech — in English, Chinese, or any other language — is full of systematic deviations from "citation" (roughly, dictionary pronunciation) examples. And tone is not fundamentally different in that respect from other features.

I should add that in John's next few phrases, he illustrates several consonant assimilation/deletion phenomena. Maybe I'll post about them at some point — they illustrate a claim that I often make to phonetics students, which is that a few tens of seconds of randomly chosen speech, even in a well-studied language like English, is likely to contain some interesting and systematic phonetic phenomena that have never been studied. ]

Given the source it's probably worth saying that he doesn't sound black at all (to my ears), though most black men can't avoid it no matter how standard they speak.

Antariksh is especially on point: language teachers, even or especially when they're a native speaker of the language in question, normally lack the linguistic insight to understand this process and that can not only waste time but lead to unnecessarily 'funny' pronunciation habits.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Michael Watts said,

February 7, 2018 @ 8:21 pm

I really enjoy thinking about Chinese prepositions and how they relate to English prepositions, so I'm going to tangentially expand on this to the best of my understanding.

English prepositions serve two roles (well, two that I'll identify here): they can indicate a location in relation to their object ("behind the door"), or they can mark an element of a verb phrase ("I've heard of you"; "he lectured on the evils of literacy for over an hour").

(I'm not totally clear on whether we believe that "for over an hour" in that example is considered part of the verb phrase or not, but the words I'm thinking of would be used for this kind of adjunct, which does not need to be licensed by the verb, too.)

In Mandarin Chinese, those two roles are filled by two very distinct word classes. Locative markers appear after the noun phrase that is their object. In the utterance 不仅在道义上失败了, 上 (up / on / above) is such a marker, and it's appearing after its object 道义 (morality). Verb assisters appear before the phrase that they're marking, and the phrase, including the assister, appears before the verb. In the example utterance, the verb is 失败 (fail), and we see 在道义上 preceding it as a complement.

The syntax of the sentence makes it very clear that this 在 is one of those verb-phrase-constituent markers. Whether that makes it a "preposition" is more of a philosophical question.

Michael Watts said,

February 7, 2018 @ 8:24 pm

Interestingly, as far as I know, those verb phrase constituent markers all share their citation pronunciation and spelling with a verb.

Bob Ladd said,

February 8, 2018 @ 1:59 am

Thanks, Mark. This is what I was trying to say in my comments on VHM's original posting, but I said it without real live examples. I should have waited…

Chris Button said,

February 8, 2018 @ 12:33 pm

If I may take this point a little further, I therefore think John McWhorter's problem is less about mutation of lexical tone as conditioned by its tonal environment (lexical or intonational) since he seems to be able to associate the tones even when distorted (just like he can associate the /k/ in "cot" with the /k/ in "king"), but rather about a confusion of stress with tone/pitch (as his comment on "mei banfa" made clear). I often read how stress is supposed to have an inherent association with shifts in tone/pitch, but a more accurate statement would be that stress has tendency to intonationally attract or lexically support shifts in tone/pitch, but is certainly not indivisible from such shifts.

D.O. said,

February 8, 2018 @ 3:40 pm

This is hugely interesting, but still doesn't answer the question, does it? My (very very very) limited experience (and not with Mandarin or any tone language) whispers to me that you should try to say things reasonably well, but do not sweat it to much. By the time you remember (in causal fast speech) not to say "yesterday" when you mean "tomorrow", it will fall into place more or less.

jih said,

February 12, 2018 @ 2:18 pm

Maybe there is another way to approach Prof. McWorther's question. In the case of languages with a very low lexical tonal density (pitch accent languages) it is not unusual for L2 learners to completely ignore tonal distinctions. For instance, it would appear that you can communicate in Swedish reasonably well without bothering about lexical tone, since that is what has happened historically in the Swedish varieties spoken in Finnland (and once spoken by bilinguals in Texas). The same appears to be true about Japanese and other pitch-accent languages. I am familiar with instances where a linguist produced a description of a pitch-accent language without even noticing that they were ignoring lexical and morphogical contrasts realized by native speakers through tonal means.

Regarding the question of consonants vs vowels in English, it seems reasonable to conclude that cansanants ara mara ampartant than vawals, sanca ya can raplaca all vawals wath tha sama vawal (ar wath spacas). wathat affactang cammanacatan that mach. This is certaintly true of the written English language (common Intro to Linguistics exercise). I do not know if anybody has done the experiment with auditory stimuli (maybe somebody has?).

I do not know Chinese, so I do not know how important tones are to get the meaning of an utterance across. Maybe someone has done the experiment? The fact that Chinese speakers sometimes communicate in pinyin without tone, would indicate that in writing you can get a lot of meaning across by allowing readers to guess the intended lexical tones.

A different matter is whether you actually want to sound like a native speaker or someone with some degree of competence in the language.

Philip Taylor said,

February 12, 2018 @ 2:59 pm

(In response to "jih") — "I do not know how important tones are to get the meaning of an utterance across". I can illustrate what I perceive as the importance through a real-life example. Very (very) early on in my Chinese-learning period, I went into a Chinese restaurant where my wife was working as a waitress (she is Chinese/Vietnamese). Wanting to be friendly to the other Chinese staff who worked there, I asked one of them "Nǐ zěnme yǎng ?" I received a look of blank incomprehension. I asked again "Nǐ zěnme yǎng ?". Still total lack of comprehension. Finally my wife intervened. "He's trying to say 'Nǐ zěnme yàng ?", she said. "Ah!" was the response; "Wǒ hěn hǎo, xièxiè. Nǐ ne ?". "Wǒ hěn hǎo !", I replied, delighted to have finally been understood. And the problem ? I was asking the question with an English-style falling-rising inflection on the final syllable, where in practice a pure falling tone was required. One tonal error, and complete lack of communication.

jih said,

February 12, 2018 @ 4:33 pm

In response to Philip Taylor. Thanks!

Yours is an example of what may happen in Chinese if you use the wrong tone for a word. That would be like keeping all vowel distinctions in English but saying "keep" instead of "cup". What I had in mind was adopting the strategy, as a learner, of always using a flat tone, but without introducing English intonation for questions (!), and completely ignoring tone in perception when you listen to Chinese (that is, without making the effort to learn the lexical tone of any words).

I think this may be testable experimentally and quantified answers could be provided; e.g. "with this specific set of stimuli, a group of native speakers was able to correctly identify the meaning of x% of words or phrases after they were resynthesized with flat pitch contours."

This, of course, applies to any other lexically contrastive feature in any other language. Spanish has lexical stress. How understandable would your Spanish be if, as a learner, you decide to use a strategy of always placing the stress on the last syllable of the word or phrase, as in French? My guess: almost 100% intelligible. It would be harder to understand, I believe, if, instead, you still don't care about lexical stress, but place stresses on random syllables).

Chris Button said,

February 12, 2018 @ 9:57 pm

@ jih

I think the difference between Spanish and English is that English speakers often ignore potential pitch shifts on stressed syllables since schwa reductions can compensate (e.g 'infor'mation tech'nology being produced as 'information tech'nology with the ' symbol marking a pitch/tone change on a stressed syllable). I believe this may also be done in Spanish but it does then render the phrase less clear since Spanish has no schwa reductions such that intonational tone shifts are its most salient markers of stress (among other cues).