Headlessness in North Korean propaganda

« previous post | next post »

[This is a guest post by Jichang Lulu]

After coverage of dotage and DOLtage, as diagnosed by the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), Victor Mair's latest Korean-themed post deals with a more serious condition: headlessness.

Varieties of the ailment have been reported in, e.g., chickens and compound nouns, but the latter sense would be out of place in KCNA vocabulary; (at least South) Korean linguists would talk of nouns 'lacking a nucleus' (핵어(核語) 없는 haegeo eomneun / 무핵(無核) muhaek 합성명사(合成名詞) hapseong myeongsa) rather than a 'head'. Another candidate for headlessness is the North Korean state itself, per OPLAN 5015 (작전계획(作戰計劃) 5015 jakjeon-gyehoek ogong-iro). Said PLAN involves a 'decapitation' (참수(斬首) chamsu) strike against Kim Jong-un. He's supposedly familiar with the nitty-gritty of the PLAN, reportedly obtained by hacking into South Korean military networks. The South Koreans, rumour has it, are speeding up their defence upgrade plans, so it's understandable any potential decapitees would feel uneasy.

We'll fulfill the plan ahead of time. Source: История миров.

Those are eyes that were his nipples

A further headless construct this post is mostly not about is Xíngtiān (形天 (also 刑天), Korean reading 형천 Hyeongcheon), who, according to the Classic of the Mountains and Seas (Shānhǎi jīng 山海經 산해경 Sanhaegyeong), was beheaded in battle but composed himself, turned his nipples into eyes and his navel into a mouth and continued to fight, or at least was able to perform a dance with his axe and shield:

形天與帝至此爭神,帝斷其首,葬之常羊之山,乃以乳為目,

Xíngtiān yǔ Dì zhì cǐ zhēng shén, Dì duàn qì shǒu, zàng zhī Chángyáng zhī shān, nǎi yǐ rǔ wéi mù, yǐ qí wéi kǒu, cāo gān qī yǐ wǔ.

Xingtian 形天 in the illustrated Shanhai jing by Jiang Yinghao 蒋应镐, early 17th century edition kept in the Harvard-Yenching Library, via Shuge 書格.

Xingtian is often mentioned in later literature. A relatively recent example is in 袁枚 Yuán Méi's Xù Zǐ bù yǔ 續子不語 (What the Master did not discuss, continued, affectionately known as Confucius still not say; available on ctext.org):

曾飄至一島,男女千人,皆肥短無頭,以兩乳作眼,閃閃欲動;

Céng piāo zhì yī dǎo, nán nǚ qiān rén, jiē féi duǎn wú tóu, yǐ liǎng rǔ zuò yǎn, shǎnshǎn yù dòng; yǐ qí zuò kǒu, qǔ shíwù zhì qián, xī ér dàn zhī; shēng jiūjiū bù kě biàn. Jiàn Qiānguāng yǒu tóu, qún xiang jīngchà, nán nǚ bī ér shì zhī, qí zhōng gè shēn yī shé, cháng sān cùn xǔ, zhēng shì Qiānguāng. Qiānguāng bēn zhì shāndǐng, yǔ qí zhòng pāo shízi jī zhī, qí rén shǐ sàn. Shízhě yuē: "Cǐ 'Shānhǎi jīng' suǒ zǎi Xíngtiān shì yě, wéi Yǔ suǒ zhū, qí shī bù huài, néng chí gān qī ér wǔ."

Once [Wáng Qiānguāng 王謙光] drifted until reaching an island where a thousand people lived, men and women. All were fat and short and had no heads. They used their nipples as eyes, sparkling and shifting, and their navels as mouths. They took food before them, sucked it in and ate it. They made chirping, indistinct noises. When they saw Qianguang had a head, the crowd was stunned. Men and women pressed forward to see him. Each stuck out their tongue from their navel, more than three [Chinese] inches long, and vied with each other to lick Qianguang. Qianguang ran to a mountain top. Only when he threw stones at the crowd did they begin to disperse. Those knowledgeable say: "This is the clan of the Xingtian recorded in the Shanhai jing. He was slain by Yǔ 禹, but his corpse would not collapse: it was able to hold his shield and axe and dance.

Perambulating in the manner of acephalous poultry

Xingtian need not further concern us. The target of KCNA invective in this case was Japanese premier Shinzō Abe, described as "running around the UN stage like a headless chicken."

As in other recent cases, we owe this quaint specimen of KCNA-nese to the Agency's English translator(s). There are no chickens in the original Korean piece. The source for 'run around like a headless chicken' is 어지럽게 돌아치다 eojireopge dorachida 'chaotically/wantonly/giddily run around'. The ornithological simile might well be a passable rendering; it is certainly more creative than what colleagues did in other languages: the most literal version, as is often the case, is in Japanese (奔走する honsō-suru 'run about'); the Chinese has 骚扰 sāorǎo 'harrass'; the Russian and Spanish versions simply ignore the running-around verb.

Here's the relevant paragraph in Korean and all five translations.

얼마전 유엔총회에서 아베는 우리 문제를 두고 《대화가 아니라 압력이 필요하다.》느니 뭐니 일장연설을 늘어놓았는가 하면 각국 수뇌자들을 만나 《국제사회의 련대》를 고취하면서 유엔무대를 어지럽게 돌아쳤다.

At the recent UN General Assembly Abe said that "pressure, not dialogue, is needed" over the issue of the DPRK while running around the UN stage like a headless chicken to meet leaders of different countries so as to incite "solidarity of the international community".

不久前,安倍在联大会议上就朝鲜问题叫嚣“

Недавно на ГА ООН Абе по поводу нашего вопроса выступил с речью, что «нужен не диалог, а давление». А на встрече с главами других государств внушал им «солидарность международного сообщества».

En la reciente Asamblea General de la ONU, Abe dijo que "lo que necesita no es el diálogo, sino la presión" en referencia al problema coreano y se reunió con los jefes de Estado de varios países en busca de la "solidaridad con la sociedad internacional".

先日、国連総会で安倍はわが問題について、「対話ではなく、

A Chosun story refers to the incident, indeed using the idiomatic Korean phrase Victor cites in the post (목 잘린 닭 mok jallin dak), but this is the Chosun's translation of KCNA's English item.

That's nothing compared to what's still to come.

Headless mendicant avian puppets go berserk

A more extraordinary deployment of the KCNA translation arsenal was in order when translators had to deal with the piece titled 《민주조선》 남조선괴뢰당국은 스스로 제 무덤을 파는 어리석은 망동을 하지 말아야 한다고 강조 ("S. Korean Regime's Suicidal Acts Slammed by Minju Joson"; Sep 4th, but timeless), and in particular this verb phrase in it:

반공화국제재압박공조놀음에 광분[하다]

反共和國制裁壓迫共助놀음에 狂奔[하다]

ban-gonghwaguk-jejae-apbak-

'madly run in a game of collaborative anti-[Democratic] Republic [of Korea] sanction pressure', or perhaps 'go into a joint anti-DPRK sanction-pressure spree', or something; not an easy task.

The Chinese and Japanese versions preserve the Sino-Korean monster noun phrase, because they can. The Russian translates it, and goes with бешенствовать bešenstvovat' ('go into a rage') for the berserk part. The Spanish ignores the Sino-pile, and translates the whole thing with mendicación 'begging' or indeed 'mendicancy', perhaps thinking of 구걸(求乞)하다 gugeolhada, a favourite KCNA verb that occurs in the same story.

So what does an English translator do in such circumstances?

Here's what (guess whose emphasis):

론평은 남조선괴뢰들이 이번에 또다시 반공화국제재압박공조놀음에 광분한것은 우리의 달라진 전략적지위와 날로 급변하는 국제력학관계를 아직도 제대로 판별하지 못하고 마구 설쳐대는 무지하고 구차한 구걸질에 불과하다고 하면서 다음과 같이 강조하였다.

The recent anti-DPRK racket is nothing but a silly and clumsy behavior as they are running round like a headless chicken, being still unaware of the strategic position of the DPRK which has already undergone a change and the international relations of power which are changing on a daily basis.

评论指出,南朝鲜傀儡这次又疯狂热衷于反朝制裁打压共助闹剧,

В комментариях подчеркивается следующее:

Южнокорейские марионетки опять бешенствуют в сотрудничестве в санкциях и давлении против Республики – это является глупыми попрошайничаньями тех, кто не правильно различили изменившийся наш стратегический статус и внезапно изменяющиеся с каждым днем международные механические отношения и беснуются.

Tales actos de los títeres surcoreanos no pasa de ser una mendicación de quienes no entienden todavía la posición estratégica de la RPDC y la estructura de las fuerzas internacionales, que se cambian bruscamente.

論評は、南朝鮮のかいらいが今回、またもや反共和国制裁・

The various versions above illustrate patterns I've observed in KCNA translation strategies. The Japanese department tends to follow the Korean original very closely, sometimes at the expense of idiomaticity. The Chinese and English department make sure they render everything in the Korean original, translating Korean idioms into existing idioms of the target language, more creatively (to great international effect) in the English case. The Russian doesn't mind omitting tricky passages, and the Spanish is the freest, prioritising the appeal to (Cuban?) leftist audiences over faithfulness to the original.

These patterns will now be exemplified even more spectacularly.

Tigers out of anthills have the last laugh

The headless-Abe piece includes the following (alas only pentaglottally: the Spanish bureau declined the opportunity):

조선속담에 재미난 곳에서 범 나온다는 말이 있다.

As a Korean saying goes, sorrow is laugher's daughter.

有句俗话说,得利不可再往。

Корейская поговорка гласит: запретный плод всегда сладок.

朝鮮のことわざに楽しんだ谷に虎が出るというものがある。

The (existing) Korean saying says 'tigers (can) come out of an interesting place'. A variant of it (seemingly more common, according to Krista Ryu) has 골 gol 'valley' instead of 곳 got 'place'. Ryu and Haewon Chon, consulted for this post, seem to suggest this is not a very common proverb. Various online sources agree on the meaning: if you keep doing only fun stuff, misfortune might hit you. Perhaps by chance, the proverb is similar in sound to this one: 개미나는 곳에 범난다 gaeminaneun gose beomnanda' 'A tiger can come out of where ants come out' (what doesn't seem to be a big problem now (an anthill) could become more serious (a tiger's den) later).

The Japanese renders the 'valley' version literally: 楽しんだ谷に虎が出る tanoshinda tani-ni tora-ga deru. This doesn't appear to be an existing Japanese idiom (corrections are welcome if a close analogue does exists).

Crossing into Chinese involves a translation-theoretical phase transition. 得利不可再往 Dé lì bù kě zài wǎng, or more commonly 得意不可再往 dé yì bù kě zài wǎng 'once you got profit/what you wanted, you can't go down that way' – roughly 'don't test your luck', or 'never try to reproduce a successful experiment' as a certain scientist once taught me. This (and its variants) is a very much existing Chinese idiom, but less than obviously a "Korean saying", and certainly not the Korean saying in the original.

The Russian (запретный плод всегда сладок zapretnyj plod vsegda sladok 'the forbidden fruit is always sweet') invokes an existing Russian (and English) proverb, but again the claim this Biblical allusion occurs in a 'Korean saying' is the translator's.

The English, which depends on a visual (or Middle English) rhyme, doesn't seem to occur in the wild today: as in other cases, the obscurity of the translation has made it more effective, at least if measured by its presence in the august (online) columns of the Daily Express. The saying does, however, have an extra-KNCA existence, at least in its more standard spelling "sorrow is laughter's daughter". Indeed, KCNA's ultimate source is Charles de Bovelles aka Carolus Bovillus.

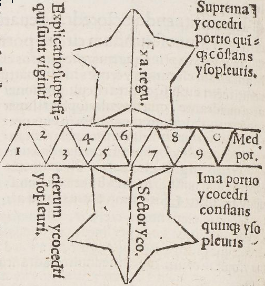

Icosahedron, in Bovelles' Liber de mathematicis/geometricis corporibus (1510) via Gallica

Icosahedral intimate jewellery begets tears

"Sorrow is laughter's daughter" occurs in several English-Korean proverb lists. Here's an online example; a recent print source is this trilingual Dictionary of Proverbs / 한국 일본 영어 속담사전 韓國日本英語俗談辭典 Hanguk Ilbon Yeong-eo sokdam sajeon. KCNA's translators might have learnt the idiom from an earlier dictionary in this tradition. (Works in the genre are also common in China, and indeed a listconceivably farmed from an English-Chinese proverb dictionary contains our saying, as well as the similarly wise (and legitimate) "A barley-corn is better than a diamond to a cock.")

Useful knowledge for the 8th of January, in The Canadian Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge, for the Year 1867 via the University of Toronto Libraries.

The obvious source for a Korean proverb lexicographer would be a collection of English proverbs. A plausible such collection is Vincent Stuckey Lean's Lean's Collectanea (1902), whose fourth volume does list our saying.

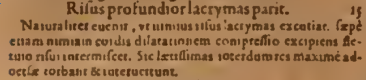

Although the adage is listed as an 'English aphorism', Lean's source isn't folk wisdom. His authority for the proverb and its Latin version (Risus profundior lachrymas parit, literally 'deeper laughter begets tears') is John Clarke's 1639 Paroemiologia Anglo-Latina in usum scholarum concinnata. Or proverbs English, and Latine, methodically disposed according to the common-place heads, in Erasmus his adages. Very use-full and delightful for all sorts of men, on all occasions. More especially profitable for scholars for the attaining elegancie, sublimitie, and varietie of the best expressions. Our Latin-English proverb is indeed there.

Said Paroemiologia is modelled after Erasmus, so that's the obvious place to go in search of the Latin proverb. Moths Ordbog, a venerable Danish dictionary from ca. 1700, attributes the adage directly to Erasmus.

As it happens, Moth is wrong: the tear-begetting proverb does not occur in Erasmus, but in the Paris edition of the Adagia, which, while duly censored as required by the Council of Trent, compensates by adding adages from other sources. This additional material includes 'a few' proverbs selected from Bovelles, and indeed KCNA's.

"Paucula proverbia Caroli Bovilli Samarobrini, unde queas de quatuor eiusdem Proverbiorum vulgarium libris iudicium facere", in Adagiorum Des. Erasmi Roterodami Chiliades quatuor cum sesquicenturia, Paris, 1571, via archive.org.

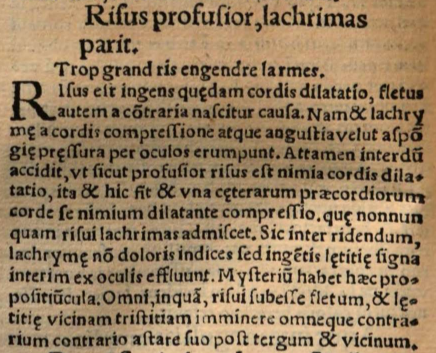

As far as I can see, the ultimate print source for KCNA's adage is Bovelles' Three books of vernacular [i.e. French] proverbs (Caroli Bovilli Samarobrini Proverbiorum vulgarium libri tres, 1531).

Caroli Bovilli Samarobrini Proverbiorum vulgarium libri tres via Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Risus profusior, lachrimas parit.

Trop grand ris engendre larmes.

Now the Latin, as the French, means 'excessive', not 'deep'; the 'profundus' in Clarke's Paroemiologia is further evidence for its provenance from the 1571 edition. Bovelles' explanation starts off physiologically: although laughter is an expansion of the heart, and tears come from its compression, as when a sponge is squeezed, sometimes the heart's laughing expansion can compress something else in there and make tears come out; such tears are signs of joy, not pain. But this little sentence has a hidden meaning (mysterium): just as tears accompany laughter, sadness looms over joy and all opposites stand near each other.

This work seems to be the first attestation of KCNA's (Middle) French proverb Trop grand ris engendre larmes; at least one other Renaissance source has it (Núñez' 1555 Refranes o proverbios en romance), but that could still come from Bovelles.

A French-language proverb collection by Bovelles, published in 1557, doesn't seem to include our tears-in-laughter proverb, but it does have a dual of sorts: there's laughter in wailing. The French version has a primeval whiff about it.

A A A Ha Ha Ha.

Vox lugentium, vox ridentium.

Charles de Bovelles, Proverbes et dicts sententieux, avec l'interpretation d'iceux (1557) via Gallica.

The Latin is more informative ('the voice/speech of the wailing is that of the laughing'). For the 'A A A' part, Bovelles refers to the Bible (Jer. 1:6-7, with 'A A A' in various Vulgates; the KJV has just one "Ah"): a triple 'ah' is almost tantamount to saying 'alas', so someone who complains 'ah, ah, ah, I've lost everything' is saying 'alas, I've lost everything'. But if one says loudly, and par aspiration (alive and well in Middle French, and even today in this interjection for some speakers), 'ha ha ha', that indicates great joy. This is how some—madly—laugh. As for the origin of the proverb cited ('one recognises a fool by his laughter'), I have no idea, but I do now know that 'a wise man is sober when he laughs, and laughs quietly and gently, without raising the loud and mad cry "ha ha ha"'.

So the idiom actually goes back to Renaissance France (and, dually, to a sort of Urschrei), flows through Trented Erasmus, English aphoristics and East Asian proverbial lexicography, and manages to excite the staid Daily Express. KCNA's English translators have the last laugh.

Headed islander hordes meet revolutionary nesophobia

An earlier exercise in KCNA comparative philology by the blogger Justrecently provides a final illustration of the Agency's many faces. In this case, the individuals described are endowed with heads, or at least not explicitly said to be headless.

Justrecently hexaglottaly quotes a KCNA item that rubbishes the Japanese. The original Korean contains a nesophobic insult:

일본섬나라족속들

日本섬나라族屬들

Ilbon-seom-nara-joksokdeul

As I noted in a comment there, Joksok, literally 'tribe' or 'clan', can mean 'gang, bunch', often pejoratively. The noun phrase thus means something like 'the Japanese island gang/horde'.

The Chinese version went with the trivial anti-Japanese slur: 日本鬼子 Rìběn guǐzi 'Japanese devils'.

The Japanese does something strange: the chosen translation is clearly meant as an ethnic slur, but it doesn't seem to be an actual Japanese expression.

日本の島国夷

Nihon-no shimaguni-i(?)

It's not even clear how the second word is supposed to be pronounced. The kanji make it obvious that the intended meaning is 'the island Barbarians of Japan', which, as usual for the Japanese department, closely follows the Korean. The reading I gave, a hybrid of native and Sino-Japanese readings, was just my first guess (and, per Nathan Hopson, "the consensus on the Internet"); there are other conceivable readings. The expression has puzzled Japanese readers as well, as evidenced by this blog post.

In all three East Asian languages, the noun phrase is (or tries to be) an ethnic slur. This is not the case in the European-language versions.

In this case, the English department was comparatively circumspect: "islanders". (The context makes it clear there's no love lost anyway.)

The Russian translation is even more circumspect: it omits the 'islander' phrase altogether. Justrecently advances as a possible explanation the relative lack of anti-Japanese feelings in Russia. This makes sense, as it's unclear how much anti-Japanese slurs would resonate with a Russian audience that is interested in North Korean propaganda in the first place. Alternatively, the Russian department might be trying to stick to safe idiomatic territory and avoiding tricky passages altogether.

The Spanish is the most creative: the ethnic slur now becomes reaccionarios japoneses 'Japanese reactionaries'. Justrecently interprets this as KCNA perhaps "trying to speak the language of North Korea's most likely allies, or comparatively benevolent bystanders." Also, talk of 'Barbarian islanders' might not go down very well in Cuba, likely an important part of the intended audience and quite possibly the foreign locale most familiar to KCNA's Spanish translators.

The relative freedom in the Russian and Spanish versions, and the excessive faithfulness of the Japanese, could also be due to shorter-staffed, less supervised departments: prioritising the English and the Chinese would be understandable. But as things stand, not even the Chinese rivals the English, which reaches Express-exciting, DOLtard-bashing, Bovillian heights.

[Thanks to Haewon Cho, Nathan Hopson, Victor Mair and Krista Ryu.]

cameron said,

October 30, 2017 @ 1:48 pm

This Memphis soul classic seems an apt reference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F7pqO7YKBt0

Chris Button said,

November 1, 2017 @ 9:38 am

I think they would have rhymed before the final "gh" /x/ began to be pulled in different directions to /f/ or "zero" that created a lot of instability in the system and ultimately had differing affects on the vowel quality. It's a good example of why one shouldn't be too prescriptive in terms of applying rhyme evidence to linguistic reconstruction at any particular stage. From a contemporary perspective, a good analogy would be the various reflexes of "cot" /kɒt/ ~ /kɑ:t/ and "caught" /kɔ:t/ ~/kɑ:t/ which rhyme for some English speakers but not for others.