Phrasebook pronunciation, or, kawnbyang der tahng dewr ler vwahyazh

« previous post | next post »

Apparently Mark and I overlapped in Paris! Who knew. I was there for une journée d'études for the CNRS project Temptypac, which was fun and interesting, plus of course being in Paris is always superbe…

My French is up to most basic communication needs, but my husband's isn't, so we shopped around a bit for a phrasebook to help him maximize touristic enjoyment while I linguistified. We found four suitable candidate pocket phrasebooks. One cost 5 euros rather than 7. It also happened to be the one that included the all-important phrase, "Je voudrais cinq tranches de jambon, s'il vous plaît", without which phrase one cannot navigate Paris at all. But the main deciding factor for us, besides the extremely valuable euros, was the pronunciation guides.

English orthography, of course, is pretty useless as a precise indication of pronunciation, and English orthographic representations of any kind won't help a naive speaker get those French phonemes that English doesn't have. But a pronunciation guide should be able to help one produce a sequence of English phones that closely approximate a comprehensible stream of French phones, hopefully without insulting your interlocutor's mother, dog or sensibilities too profoundly.

The key thing for us was that the guide should employ orthographic conventions useful for speakers of American English. Here are phrases from the three guides we rejected. See what pronunciations these suggest to you:

Phrasebook 1:

Can you tell me when to get off?

Pouvez-vous me dire quand je dois descendre?

poo-vay-voo muh deer kawN zhuh dwah deh-sawN-druh

Where's the subway [underground] station?

Où est la station de métro?

oo ay lah stah-seeyoN duh may-troh

Phrasebook 2:

Can I take my car on the boat?

Je peux transporter ma voiture sur ce bateau?

zher per trons-por-tay ma vwa-tewr sewr ser ba-to

Can I get a cash advance?

Puis-je avoir une avance de crédit?

pwee zha-vwar ewn a-vons der kray-dee

Phrasebook 3:

Where are the bus [coach] stops?

Où sont les arrêts de car?

oo sawng lay areh der kar

How long does the trip [journey] take?

Combien de temps dure le voyage?

kawnbyang der tahng dewr ler vwahyazh?

Below are some key correspondences in the three systems, listed by phrasebook number:

French schwa, as in the 1sg pronoun je

1: "uh"

2: "er"

3: "er"

Nasal vowels indicated by:

1. capital N following the vowel

2. lowercase n following the vowel

3. lowercase n or ng following the vowel

Syllables

1. indicated by hyphens

2. indicated by hyphens

3. not indicated

Low front vowel

1. "ah"

2. "a"

3. "ah", "a"

For us rhotic speakers, of course, the key thing was to get one which didn't transcribe the central vowel as 'er', which suggests to us that we should say something that ends in [ɹ]. I still remember the blinding flash of light when I realized years ago that the speech hesitations spelled "er" and "erm" in British texts are intended to sound just like the hesitations spelled "uh" and "um" in American texts. I'd been reading them internally as [əɹ], [əɹm], and if you'd asked me to read them aloud, that's how I'd have done it, even though never in my life had I heard anyone hesitate with such a noise. What a ninny.

Be that as it may, using the "er" orthographic convention, rather than "uh", poses a bit of a problem in these phrasebook pronunciation orthographies. French has a syllable-final 'r' sound. French 'r' is nothing like English 'r', but putting an English 'r' in is probably better than nothing in trying to approximate a French word with English phones. So syllable-final 'r' in these phrases should sometimes be pronounced. In Phrasebook 1, which spells the central vowel as 'uh', any syllable-final 'r' symbol in the pronunciation guide actually stands for an intended 'r' sound of some kind. But in the 'er'=schwa books, one has to distinguish between syllable-final 'r' in 'er', which is not pronounced, and syllable-final 'r' everywhere else, e.g. in 'sewr' (sur) or 'kar' (car), which is.

A similar though to my ear less severe problem is posed by the syllable-final orthographic nasals. In phrasebooks 2 and 3, sometimes they're really there; other times they're not, when they're just present to indicate a nasal vowel. So, e.g., the 'n' in 'ewn' (for une) in Phrasebook 2, is intended to be pronounced, but the 'n' in 'a-vons' (for avance) ideally shouldn't be; rather the preceding vowel should just be nasalized. This is probably a very minor issue, considering the degree of pronunciation imprecision involved anyway, but it's nice that Phrasebook 1 at least makes an effort to distinguish between nasalized vowels and syllable-final nasal consonants.

Weirdly, in the English portion of the texts of books 1 and 3, both British and American terms are provided, with the British in square brackets following the American. Given that the pronunciation orthography in 1 is useful for rhotic dialects while 3 is intended for non-rhotic ones, I would have thought that in 3, the British term would be the main one, with the American in square brackets following, but not so.

Both phrasebooks 1 and 3 are published by Berlitz. I don't know why they offer two French-English phrasebooks, unless it's because the pronunciation guides differ; the binding and content were different but the price was the same. There wasn't any obvious indication up front, though, that one might be better for Americans than the other. Phrasebook 2 is published by Lonely Planet. I made the notes above from photos of single pages I took in the bookstore. Ironically, I'm afraid I don't have the phrasebook we actually bought in front of me, so I can't tell you who published it, but it was a) 2 euros cheaper and b) like phrasebook 1 in many of its orthographic conventions, so useful for rhotic speakers. It also was the one told how to order five slices of ham, which as I note is key.

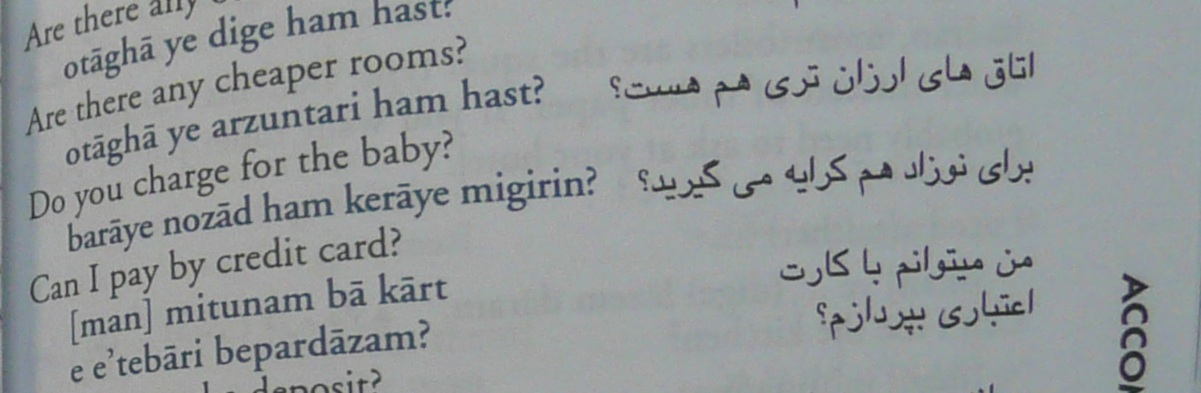

Finally, just out of curiosity, I also had a quick look in an English/Persian phrasebook published by Lonely Planet on the way out, and to my astonishment it used a completely distinct pronunciation orthography! Attached is a photo of part of a page of that one, so you can see how different it is (as usual, click to zoom). They've got macrons over the 'a's and everything. Seems like the particular orthographic pronunciation conventions in these phrasebooks varies at the whim of the author; it's certainly not standard by publisher, at any rate.

I find the whole phrasebook orthography situation pretty weird. It's another clear example of a situation in which providing English speakers with the rudiments of a linguistic education — in this case, a smidgen of basic phonetics and a bit of a clue about the IPA — would be useful in a seriously practical way. If that were generally part of the secondary education of most English speakers, phrasebook writers could stop inventing their own weird systems and standardize.

John Cowan said,

June 27, 2008 @ 8:07 pm

In the first example, surely "kawN" is a typo for "kwaN", but whose, yours or the guidebook's?

Timothy M said,

June 27, 2008 @ 8:12 pm

"I still remember the blinding flash of light when I realized years ago that the speech hesitations spelled "er" and "erm" in British texts are intended to sound just like the hesitations spelled "uh" and "um" in American texts."

Oh my god! ::blinding flash of light::

Benjamin Zimmer said,

June 27, 2008 @ 8:33 pm

There's nothing particularly phrasebook-y about that rendering of Persian. It looks like a fairly standard romanization. Google Book Search shows the transliteration system for this guidebook, and it squares with what you find on, say, Wikipedia.

language hat said,

June 27, 2008 @ 8:42 pm

What Ben Zimmer said, but also: it's shocking that they don't indicate stress, which is strong and distinctive in Persian. One little tick mark per word and you render the sentence infinitely more comprehensible.

lynneguist said,

June 27, 2008 @ 9:37 pm

"I still remember the blinding flash of light when I realized years ago that the speech hesitations spelled "er" and "erm" in British texts are intended to sound just like the hesitations spelled "uh" and "um" in American texts."

I blogged this issue last month. The worst bit of it is that it took me more than 12 years of living in non-rhotic countries before I figured that one out. (It was seeing 'er's in subtitled versions of Friends that did it.)

Aidan Kehoe said,

June 27, 2008 @ 10:20 pm

That filler convention ist possibly more irritating to those few million of us who follow British orthography and get their media yet speak a rhotic English. Though I suppose I did conceive of them as having a different filler vocabulary, to be honest, just as do the French.

David Eddyshaw said,

June 27, 2008 @ 10:48 pm

John Cowan –

No typo: "quand" is k + nasalized open o, which is what the ghastly phrasebook orthography is trying to convey

Kellen said,

June 27, 2008 @ 10:52 pm

i remember trying to pick up some portuguese on my own a couple years back, and went the route of phrasebooks since i had friends with whom i could practice. the lonely planet brasilian transliteration was horrible, though perhaps in part because of the strong differences in pronunciation between rio, for example, and just about anywhere else.

but one of the worst was for mandarin. before moving to china my friend picked up the lonely planet phrasebook. i was shocked to see it lacking pinyin, an otherwise standard and widely used transliteration system in the mainland. while i personally hate pinyin as a system and think it needs a massive overhaul, it IS what the locals are using and it's not THAT hard to figure out. since they even use it on street signs here, it seems a much better idea to have a quick chapter in the phrasebook about how to pronounce pinyin, and then just use that for the rest of the text.

don't even get me started on arabic phrasebooks.

Robert Coren said,

June 28, 2008 @ 12:16 am

As to "er" = "uh", etc.: By the same token, I was many years an adult before I understood what Christopher Robin was actually saying when he said "His name is Winnie-THER-Pooh".

Aaron Davies said,

June 28, 2008 @ 1:12 am

Wow, so that's where horrible "tourist accents" come from! The minute I started reading those aloud (especially two and three) I immediately pictured myself as a typical "ugly American" bellowing a slow series of equally-stressed nonsense syllables at his waiter. Having never needed such phrase-books (especially, of course, for the languages I actually know), I don't think I ever quite grasped how bad they seem to typically be.

dr pepper said,

June 28, 2008 @ 2:11 am

I never thought of "er" and "uh" as being the same because i was used to reading them together, as in:

"The thing is, er, uh", said Fred, stumbling over his words.

So would a non rhotic person read that as two "uhs"?

Timothy M said,

June 28, 2008 @ 4:43 am

"By the same token, I was many years an adult before I understood what Christopher Robin was actually saying when he said "His name is Winnie-THER-Pooh"."

::epiphany:: Now I understand what the characters in Great Expectations were saying when they said "what I meantersay"!! Shame on my high school English teacher for not telling us (not knowing?) that "er" really meant "uh".

Michou said,

June 28, 2008 @ 5:30 am

Pouvez-vous me dire quand je dois descendre?

… deh-sawN-druh

'descendre' ends with -dr, not druh.

JREL said,

June 28, 2008 @ 5:32 am

Can I just add that as a non-native English speaker who has used English phrasebooks for a variety of languages, pronunciation guides of this sort are thoroughly confusing. The world has been gifted with the IPA, a great tool which, despite its flaws, does a marvellous job in unambiguously representing speech sounds, so why not disseminate it more widely and use it also in non-professional publications? In my French-medium primary school, we learnt the rudiments of IPA (which admittedly makes a lot more sense in French, except e.g. for /y/) — I would concur with Heidi that more teaching of the IPA would go a long way in helping produce more effective phrasebooks (at least as far as pronunciation is concerned).

Lugubert said,

June 28, 2008 @ 6:18 am

Yes, JREL, confusing.

My "Catalan in three months" might have been useful, despite its exagerrated claim, but its US(?) pronunciation guides aren't even misleading. Like "ler 'kahz-er' per-tee-ter", supposedly corresponding to "la casa petita".

British English can be as difficult. I was fascinated by a translation of Rudyard Kipling's Kim many years before getting into English, so for perhaps 40 years or more, I read the name

"Hurree Babu" like, "huh-reh …" before realizing that a proper transcription should probaly be "Hari Babu". One of my favourites is the sorceress Huneefa, whose name I from Swedish thought of as rather "huh-neh-fuh", but which must really be Hanīfa (Arabic/Urdu for 'the true believer').

David Eddyshaw said,

June 28, 2008 @ 6:39 am

The old British Raj transliterations of Indian terms use 'u' (as in British Received Pronunciation 'but') for the similar but not identical Hindi/Urdu 'a', as in 'Punjab', ultimately from Persian 'Panj A:b', 'Five Waters', 'suttee' from Sanskrit 'sati' 'good woman' etc

This catches out people like BBC newsreaders, too: they often come out with 'Poonjab' in a misplaced desire to be authentic.

The schwa-like pronunciation of the short 'a' in Sanskrit is mentioned in Panini's ancient and celebrated grammar of Sanskrit, in the shortest grammatical statement ever:

'a a'

I gather it needs to be interpreted in context.

Antoine Cassar said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:03 am

As a linguanaut and writer of multilingual verse, I find these inconsistent systems for indicating pronunciation in phrasebooks not only confusing, humorous and macaronic but also a little annoying. I too wish they would standardise by using the IPA! A page or two to explain basic IPA at the beginning of the book or as an appendix would be far more useful for the traveller wishing to engage with local populations in their own tongue, instead of having to grapple with variously invented codes and risk sounding even more 'foreign' than if simply resorting to a more 'international' language!

I learnt IPA during my first year at university in England – but it wouldn't be a far-fetched idea to introduce it to students at some point during their teenage schooling. There would be no reason to go into much detail, a simple introduction would suffice, just to ensure young students are aware of its existence and use. Given that IPA (I believe – please correct if I'm wrong) can be used to describe the phonetics of practically any language across the earth, teaching adolescents about IPA would be a small contribution towards developing their planetary conscience, much like when teaching world geography or elementary astronomy. The problem, of course, is that education syllabi tend to give too much focus to the national context, thereby consolidating an ever-less complex received identity.

Antoine Cassar said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:14 am

David Eddyshaw said:

" The schwa-like pronunciation of the short 'a' in Sanskrit is mentioned in Panini's ancient and celebrated grammar of Sanskrit, in the shortest grammatical statement ever:

'a a' "

How very intriguing! So if I have understood correctly, "a a" in Sanskrit is a full grammatically sufficient sentence? What does it mean?

john riemann soong said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:15 am

About the schwa-vowel commonly shared across the pond as a filler phoneme… has anyone bothered to do any "philological" research about how these have developed / diverged / evolved?

French uses "euh," which uses a different vowel though rather close to the English one, and then for a comparison all the way across the world I get reminded of Chinese and Singlish discourse and topic-marking particles (boy ah — your prata ready liao. Want so much chili powder, hor. You sure or not? Very hot leh!)

Ray Girvan said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:38 am

Timothy M> ::epiphany:: Now I understand what the characters in Great Expectations were saying when they said "what I meantersay"!! Shame on my high school English teacher for not telling us (not knowing?) that "er" really meant "uh".

I'm unsure about that one. That's Joe Gargery, a blacksmith in a small village in the Kent Marshes in the early 1800s. He'd most likely have a strongly rhotic southern rural English accent, and might well pronounce the r.

For me, the epihany was recognising that the disapproving "Tut, tut", "Tch, tch" or "Tsk, tsk" said by comic-book characters represented a dental click. And yet, at least jokingly, people do say "Tut, tut" sometimes.

Another one in print is "eh" – pronounced "ay".

Benjamin Zimmer said,

June 28, 2008 @ 8:49 am

For more on er, Winnie Ther Pooh, etc., see my post, "Pinker's almer mater."

Faldone said,

June 28, 2008 @ 8:51 am

The problem with using IPA is that you have to teach people how to pronounce the IPA symbols. Examples from English are going to face all the same problems of regional variants that the phrase books already face. The only way to do it is to teach IPA with actually pronounced sounds produced by professional voices. This would require recordings or computer sound files, not the sort of thing that's going to be helpful to the average person looking for a phrase book when in the country in question.

David Eddyshaw said,

June 28, 2008 @ 9:27 am

Antoine Cassar:

No, 'a' is not a full sentence in Sanskrit.

Panini's grammar is wiritten in a highly sophisticated special notation very remote from any normal language. The aphorisms it consists of are interpreted in the light of all the previous aphorisms and are not stand-alone.

It is incomprehensible without a commentary; even the commentaries have commentaries.

The reason for its remarkable from is that it is intended to be memorised in its entirety by the budding pundit [hey, another 'u' for Sanskrit 'a'!] , so brevity is pursued at all costs. It must have been the culmination of a long tradition of highly formalised grammar-writing.

There's a wikipedia entry for Panini, which while not exacty lucid itself, gives a good idea of the highly technical nature of his work.

Timothy M said,

June 28, 2008 @ 10:43 am

In response to Ray Girvan: Ah, well then I don't know what to think. I didn't know about the "tut, tut" either though – which is also from Winnie the Pooh. Now I know that it's ::dental click, dental click:: "looks like rain."

Speaking of that though, I'm almost positive that in Disney's original Winnie the Pooh cartoon, Christopher Robin DOES say "tut, tut."

::several minutes of searching on YouTube::

Bingo. http://jp.youtube.com/watch?v=C4NB-3HmZnM&feature=related

4:01 minutes in.

I guess Disney didn't know much about British English either.

Kate said,

June 28, 2008 @ 11:17 am

"I still remember the blinding flash of light when I realized years ago that the speech hesitations spelled "er" and "erm" in British texts are intended to sound just like the hesitations spelled "uh" and "um" in American texts."

"Now I know that it's ::dental click, dental click:: 'looks like rain.'"

HOLY CRAP!

(As a side note, I hate those pronunciation guides in guidebooks. They send me the wrong message every single time.)

Ray Girvan said,

June 28, 2008 @ 11:41 am

> Christopher Robin DOES say "tut, tut."

Yep. I strongly suspect, on no particular evidence, that it fed back into English somehow: i.e. "dental click, dental click" was written down as "Tut tut" and people, not recognising it as such, started saying "Tut tut". I vaguely recall reading a similar story about "ain't" getting into the language via its written form, which was actually meant to represent something pronounced like "an't" or "ənt".

Robert Coren said,

June 28, 2008 @ 12:25 pm

Ray Girvan's and Timothy M's remarks about "tut, tut" remind me that I was going to suggest that "er" has entered the spoken language of rhotic speakers as a result of seeing it frequently in print; mostly, I think, as a deliberate, artificial representation of hesitant speech.

While I'm here, I'll observe that the series of French textbooks used in my high school employed (a somewhat simplified form of) IPA to impart French pronunciation, and I've always been glad that they did.

Robert Coren said,

June 28, 2008 @ 12:29 pm

Benjamin Zimmer points me to his post about "Winnie-ther-Pooh" and related matters, in which he also mentions the non-rhotic "Eeyore", another realization I came to relatively late in life. It also reminds me of an episode in a childhood version of "Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks" in which Till gets a donkey to "read" by putting hay between the leaves of a book on whose facing pages are the letters "E" and "R". (I assume that in the original German these would have been "I" and "A".)

language hat said,

June 28, 2008 @ 1:14 pm

he also mentions the non-rhotic "Eeyore"

Cue blinding flash of light!

(And hey, congrats on the preview!)

Nik Berry said,

June 28, 2008 @ 1:27 pm

I'm a Brit living in the Midwest, and I have terrible trouble trying to buy "A carton of Camel Filters, hard pack". First the clerk will ask how many packets of Carltons I want. Having tried to pronounce the word as rhotically as I can, they'll finally get it. They'll then go and get a carton of soft packs.

I'd been here for years before I worked out how on earth someone could hear "hard" as "soft". They hear a word with no 'r' in it, and "hard" to them definitely has an 'r'. It's not just the rhotic issue though – my 'a' in hard is probably closer to the Midwest 'o' in soft.

But I cannot talk rhotically without it sounding like an appallingly bad imitation of an American accent.

I printed out what I wanted once, and handed the paper to the woman at the checkout. She was so astonished by this that she gave me the wrong thing anyway.

Karen said,

June 28, 2008 @ 2:45 pm

Nik – ask for Camels in a box ;-)

Isn't Eeyore not only non-rhotic, but aitch-dropping?

Robert Coren said,

June 28, 2008 @ 3:00 pm

Karen asks:

:Isn't Eeyore not only non-rhotic, but aitch-dropping?

Well, yes, but apparently not all languages (and dialects) hear that "H" anyway. See my reference above to "Till Eulenspiegel"; and I know of at least one instance (from Mahler's Des Knaben Wunderhorn songs) of a German transliteration of a donkey's bray as "ija!"

Q said,

June 28, 2008 @ 3:11 pm

So how did they describe the vowel sound in words like "feu" (fire)? That one doesn't even exist in English and was a pain to learn.

@Nik Berry: Depending on where you got them, your accent may not have been the problem. Some convenience store clerks simply aren't that bright, because they've done things like that to me and I'm a native Midwesterner.

David Eddyshaw said,

June 28, 2008 @ 3:12 pm

Eeyore surfaces as "Iya" in Leonard Wolf's Yiddish version of Winnie the Pooh as well.

Eeyore seems to take to Yiddish very naturally somehow …

"Dos Farentfert Zeyer a Sakh. Keyn Vunder Nisht."

Adrian Bailey said,

June 28, 2008 @ 3:24 pm

"kawnbyang der tahng" is truly gruesome and parodic. Since American o is long, "con" > "kawn" and "temps" > "tahn(g)" are unnecessary explanations, so I assume it's a British English rendering. But even for us in the UK, "con-bee-ann duh tonn" is much easier and closer.

Rubrick said,

June 28, 2008 @ 3:54 pm

I was somewhere in my teenage years before I realized that "sigh" was a voiced expulsion of breath, rather than a word Charlie Brown said.

Also, regarding the photograph of the French-Persian phrasebook: are there places in France where they give away babies for free?

dr pepper said,

June 28, 2008 @ 4:14 pm

Hmm, my father went to a british boarding school and later to Oxford. When a was a small child and he read Pooh to me, he pronounced the r's in "ther" and "Eeyore" distinctly. I guess he must not have heard any english people pronounce it differently because he was usually interested in such things and had a good ear for language.

But what i have trouble understanding is the idea of deliberately using an r to spell something that you don't intend to have an r sound, i seems kind of wasteful. It would be like me, who can't pronounce the pn combination in "pneumonia", deliberately using p as a silent letter.

Faldone said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:12 pm

The mention of Winnie The Pooh in other languages prompted me to pull my copy of Winnie Ille Pu off the shelf to see how Eeyore was translated into Latin. It's third declension, Ior in the nominative. The translator is Alexander Lenard, a Hungarian by birth but said by Robert Graves to be a polyglot with no discernible accent. What accent it is that's not discernible isn't mentioned, but one would imagine it's some variety of British from the fact that it was Robert Graves who said that it was not discernible.

http://mek.oszk.hu/02700/02764/html/

john riemann soong said,

June 28, 2008 @ 7:42 pm

"It would be like me, who can't pronounce the pn combination in "pneumonia", deliberately using p as a silent letter."

It took me a while to realise French pronounces the /p/ in ps/pn/pt/etc. words.

Ray Girvan said,

June 28, 2008 @ 8:00 pm

Re rhotic "er"

It's an interesting one. I have to admit I use it. For general unplanned pauses, I'm told I use "uh" (ie əəəə). For planned pauses, particularly for "can we think this thing out?" situations, I use "errrr".

I don't know how general a perception this is. I'm a horrible code-switcher: I swing between English RP and what I was brought up with, a kind of highly rhotic English southern rural mixed with Estuary (the latter reactivated by moving to Devon).

K Bodden said,

June 28, 2008 @ 8:19 pm

When the singer Sade (who is Nigerian) first came to attention here in the United States, her albums carried a sticker saying, "Pronounced 'Shar-day'." And to this day, we pronounce the hard r. But that pronunciation must have been provided by her British record company, as the correct pronunciation (I'm told) is (ʃɑːˈdeɪ).

Johanna Brugman said,

June 28, 2008 @ 11:16 pm

My Lonely Planet guidebook for Namibia has a section at the back where it gives "helpful" words and phrases for Afrikaans, German, Oshiwambo, Otjiherero, Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara), !Kung, Silozi and Setswana. (I'm not sure why German's there, because your chances of meeting a German-speaking Namibian who can't speak English are slim, and Setswana speakers only constitute about 0.3% of the population, so that section’s not likely to be much use, either.) All examples seem to be in orthography, and there are no pronunciation guides, with the exception of a short list of English "equivalents" for Afrikaans vowels (e.g., 'u' as in the 'e' in 'angel', but with lips pouted).

Their introductory paragraph on Khoekhoe isn't too bad, except for the part where they say that clicks "are created by slapping the tongue against the teeth, palate or side of the mouth". At least they refrain from trying to explain how to produce them. Unfortunately, the description of the "click-ridden languages of Namibia's several San groups" is less impressive:

In normal speech, the language features four different clicks (lateral, palatal, dental and labial), which in Namibia are usually represented by //, ǂ, /, and !, respectively. However, a host of other orthographies are in use around the region, and clicks may be represented as 'nx', 'ny', 'c', 'q', 'x', '!x', '!q', 'k', 'zh', and so on. To simplify matters, in the very rudimentary phrase list that follows, all clicks are represented by '!k' (locals will usually forgive you for ignoring the clicks and using a 'k' sound instead).

I'll just skip right over the first two sentences and point out that by replacing every click with [!], they have effectively neutralized 47 of 89 possible syllable onsets (assuming they're talking about Ju|'hoansi). They also don't say anything about the 8-way vowel phonation contrast (oral and nasal versions of modal, breathy, glottalized and epiglottalized vowels) or the fact that there are four tone levels. So my guess is that your attempt to ask !Kang ya tsedia/tsidia? 'What is your name? (to m/f)' may get you points for effort, but the response is unlikely to be your interlocutor’s name.

Robert said,

June 28, 2008 @ 11:50 pm

I had a similar realization when I realized that when Americans use o to transcribe something phonetically, instead of meaning ɒ, they sometimes mean ɑ, which I am accustomed to see written ar.

Jonathan Breit said,

June 29, 2008 @ 12:47 am

Panini's "a a" means /a/ –> [ə], i.e. short "a" is realized phonetically as schwa. It doesn't have anything like a brackets or arrows because it is originally an oral work.

Morgan said,

June 29, 2008 @ 7:48 am

It took me a while to realise French pronounces the /p/ in ps/pn/pt/etc. words.

Swedish and thus presumably also the other Scandinavian tongues pronounce the k in kn words like knä (knee), knåda (knead), etc, and onomatopoetic words like "knax" (for the snapping sound such as the sound of a joint popping). Of course, also the g in gn words (I guess these would historically have been related) such as gnida (rub).

Bernhard Fisseni said,

June 29, 2008 @ 9:27 am

As for IPA, Faldone is certainly right: It needs explanation, and does not help much on its own.

I remember reading IPA in our English books; I though I had it figured out, but in nine years of English no-one ever told us that English does not have final devoicing, i.e. that there is a difference in pronunciation between a "bet" and a "bed", "rice" and (to) "rise" etc. This was well represented in IPA – but as German does not indicate final devoicing in orthography (e.g. "seid" and "seit" are pronounced alike, "zite" ;-)), I didn't guess that IPA would have.

So in the eleventh year after starting to learn English, I learnt about IPA, final devoicing and the lack thereof in a phonetics lesson: a blinding flash of light indeed. (My pronunciation of English "mouze" and "houze" is still recovering from overgeneralisation and an unjustified trust in orthography.)

Laura said,

June 29, 2008 @ 11:06 am

As part of my high school choir curriculum, we were required to learn some basic IPA symbols to help with learning to pronounce foreign languages. As an American English speaker, even the little bit I learned there has been a great help to me in understanding phonetics. I completely support the notion of teaching IPA in secondary schools.

dr pepper said,

June 29, 2008 @ 2:09 pm

I've never had any trouble pronouncing "gn" or "gny", but no matter how i try i can't pronounce "kn".

Bunny Mellon said,

June 29, 2008 @ 5:34 pm

Pepper said, i can't pronounce "kn".

You remember King Canute, the one who sat on the shore and told the tide to go back? Well, in Norwegian his name is Knut. It sounds exactly the same. Does that make it easier?

john riemann soong said,

June 29, 2008 @ 5:53 pm

There seems to be a bit of subjectivity in deciding whether something is a consonant cluster, or has an extra syllable, etc. sometimes.

Take for example, "faible" or "musique" in French.– at times, it seems that the e-muet is pronounced anyway, and I'm not talking about people from the south. Then in French Phonetics you learn that French releases terminal plosives and various other consonants in a way that English would not, such that there is the appearance of a slight schwa sound.

So I suppose "Canute" would sound 'exactly' the same as "knut" if the schwa vowel were devoiced enough such that the devoiced schwa vowel seems to be a product of extremely long voice onset time.

nbm said,

June 29, 2008 @ 10:03 pm

Returning to Yiddish briefly: I've more than once had trouble teaching those not brought up with it to pronounce "kvetch." "No, not 'kavetch,' kvetch!"

Nathan Myers said,

June 29, 2008 @ 10:53 pm

I routinely pronounce the "silent k" (knife) and similarly g (gnat), p, etc. when talking to my kids, so that when they learn to spell they won't be surprised at the "extra" letter. It hasn't affected their own speech. Talking like your friends is easy, but spelling is hard, so I knew which way to bias it.

Steve said,

June 30, 2008 @ 6:04 am

As a British non-rhotic speaker, I nonetheless distiguish between 'uh' and 'er' – neither has an 'r' on the end but 'uh' is a much shorter sound than 'er'. But maybe that's just me.

Jim said,

June 30, 2008 @ 8:49 am

As another non-Rhotic English speaker I should point out that for me the R in er does sometimes reappear when the next work begins with a vowel, eg, "Er, are you sure of that?"

Having said that though, I'm not sure if that's the R being sounded as per the normal rules of non-rhotic pronunciation (eg, "fair enough" becoming "fairy nuff") or the appearance of the "informal" intersyllable R that makes people write angry letters to the BBC when they detect continuity announcers using it in phrases like "the howdah (r) is higher than the ha-ha (r) over there".

Aaron Davies said,

June 30, 2008 @ 9:27 am

Japanese has an interesting two-part hesitation marker: えと ("e to" in the common transliteration scheme, which conveniently corresponds to [e to] in IPA). I've never had occasion to hear it in "real" spoken Japanese, only scripted, so I'm not sure how it's used in practice–it would seem that either a multi-syllable hesitation marker would have to be repeated, or only a fixed amount of hesitation is allowed in that language.

john riemann soong said,

June 30, 2008 @ 7:23 pm

Stressed "uh" is the same vowel as "plus", isn't it?

Peregrine said,

June 30, 2008 @ 11:14 pm

The Japanese えと seems to be used only once, but what the written version doesn't show is that the final vowel can be quite extended, in a sort of uhhh way (in terms of length, not sound)

Peregrine said,

June 30, 2008 @ 11:16 pm

Wow. It had never occurred to me that one migh pronounce the r in "er". I'm used to thinking of the difference in words, but hadn't extended it to ers.

Greg Morrow said,

July 2, 2008 @ 10:58 pm

While IPA is necessary for technical work, I'm not sure how useful it'll be for casual non-specialists like tourists, mostly because it makes distinctions that technical work requires that casual work does not, and because you can't explain it with print examples reliably, because you can't control the reader's dialect.

For example, I have three low vowels; many other English speakers only have two. So attempting to explain that language X has a sound like a in "father" as well as a sound like aw in "law" is just going to confuse some people. I've seen at least two different IPA notations for words that contain my middle low vowel, so there's probably dialectal variation there, too, and I doubt I could hear the difference if you tried to say it for me.

The other clear example is /r/. There are, rightly of course, lots of different r-like IPA characters. Now, which one does your reader use, and do they have a rhotic dialect?

English long-a and long-o are (so I've read) usually pronounced as diphthongs. I can't imagine you'll get very far trying to accomodate/correct that in presenting a pronunciation guide.

To get IPA to work for the tourist, you'd have to add a layer of abstraction/simplification roughly equivalent to the phonetic/phonemic difference. You're not going to be able to eliminate the tourist's accent, anyway. For a tourist, it's probably OK if they pronounce Spanish with a labiodental fricative instead of the actual biliabial one. An English speaker is going to have an infinitely easier time trying to pronounce /vaka/ than a fully accurate IPA representation, not least because they can remember what /v/ is instead of having to flip back to the front of the book to remind themselves what that symbol (IPA bilabial fricative) is.

Axel Theorin said,

July 4, 2008 @ 11:51 am

Aaron Davies, Peregrine>

えと is realized in several ways with lengthening of the first vowel, the second vowel or both. Lengthening of the first vowel is often combined with gemination of the onset of the second syllable, [ɛːtːɔ], sometimes represented in kana as えーっと.

Another extremely common filler in Japanese, あの (ano), however mainly exhibits lengthening of the second syllable nucleus.

David Marjanović said,

August 24, 2008 @ 6:01 pm

And is there a way to figure out which "a" is [æ] and which is [ɒ]?

Yes! Correct! :-)

All kinds of Standard Average European but English pronounce all those things. (With only slight variations — for example, in French word-initial x is [gz] rather than [ks].) English is the odd one out.

The trick is not to aspirate, or rather, not to give the [k] an oral release. Use a nasal release instead.

Be careful, though. The verb to house somebody really does have a [z]. "Unjustified trust in orthography" sounds about right!

Not quite: it's [ɛtɔ]. (I don't understand why the IPA uses the symbols e and o for the closed vowels.)

Nigel Greenwood said,

August 26, 2008 @ 3:36 pm

Ray Girvan said,

Timothy M> ::epiphany:: Now I understand what the characters in Great Expectations were saying when they said "what I meantersay"!! Shame on my high school English teacher for not telling us (not knowing?) that "er" really meant "uh".

I'm unsure about that one. That's Joe Gargery, a blacksmith in a small village in the Kent Marshes in the early 1800s. He'd most likely have a strongly rhotic southern rural English accent, and might well pronounce the r.

—-

I think both these comments are slightly off track. "what I meantersay" = what I mean to say. Even in a rhotic British accent "to" is never rhoticized (nobody would say "te[r] ropen the door"). I think Dickens (& Gargery) meant the "ter" to represent t+schwa.

simon said,

January 12, 2009 @ 1:19 pm

I would pronounce the r in "what I meantersay", I'm from Hampshire. Also Whinnie Ther Pooh sounds 'naturally exaggerated' with that extra r. However we say r differently, I have been accused of being non rhotic even when adding extra rs all over the place….