Trump's prosody

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday I showed a pitch contour from one of Hillary Clinton's speeches ("Political /t/ lenition", 8/7/2016), and promised to take a broader look at her characteristic prosodic styles. But today I'm going to feature one of Donald's prosodic stylings. From the Trump/Pence rally in Des Moines, Iowa, 8/5/2016:

We're gonna use great business leaders

___to work with our generals —

we're gonna make great trade deals

___where we're getting absolutely killed —

with China

___and other countries —

Donald Trump deploys this pattern rarely but effectively — and I'd be surprised to hear it from Hillary Clinton.

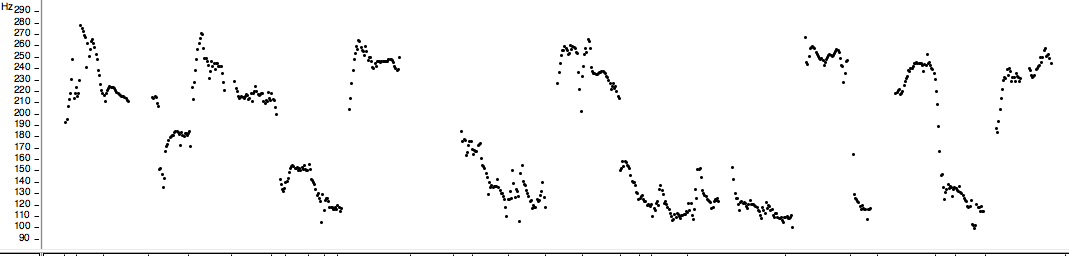

In this instance, Trump arranges the pattern as six repetitions — three pairs — of a binary pattern, in which a low-pitched region is followed by an abrupt jump to a much higher value, in some cases more than an octave up, starting with an emphasized word and continuing nearly level to the end of the phrase.

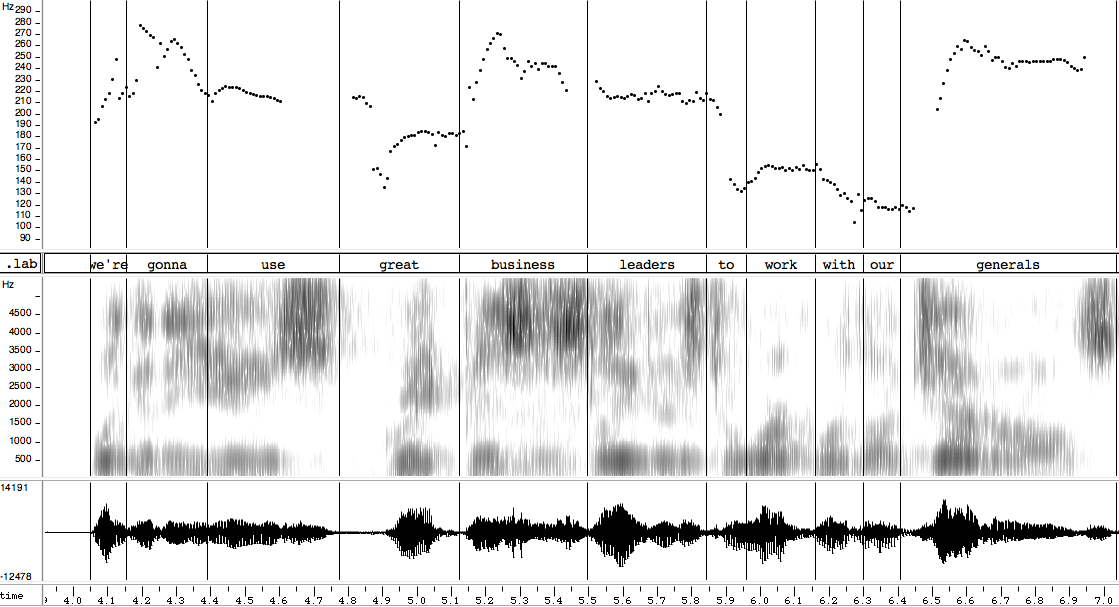

The first prosodic couplet — note that in this first case the low regions are gradually falling:

We're gonna use great business leaders

___to work with our generals —

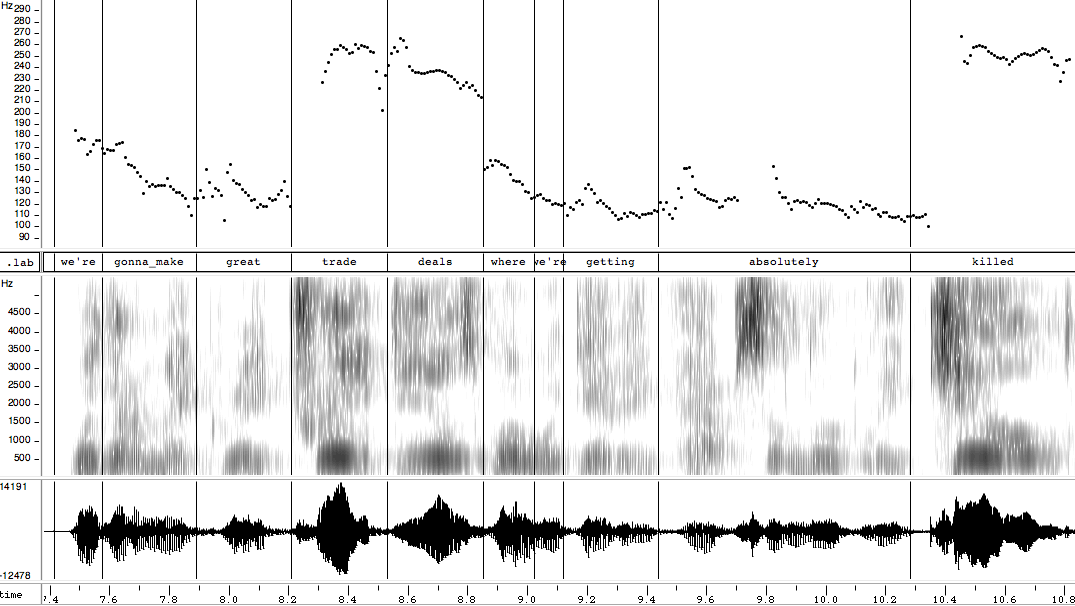

The second one:

we're gonna make great trade deals

___where we're getting absolutely killed —

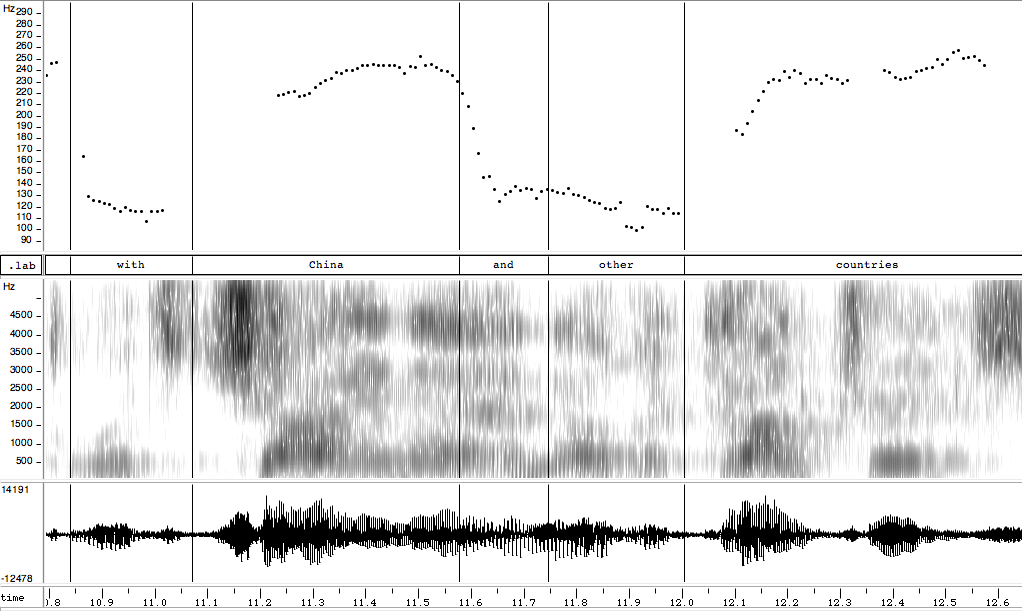

And the third — here the final high-pitched region is slightly rising at the end, unlike the earlier ones, which are level to slightly falling:

with China

___and other countries —

I suspect that there's a bit of New York City here. And I think that Mr. Trump tends to use this pattern when he enumerates problems or promises that he thinks ought to be obvious or at least already known.

But I might well be wrong. Even in well-studied languages like English, we're not very far along in understanding the nature of prosodic patterns, either in terms of form or in terms of function. Maybe the interest in political rhetoric can help us make some much-needed progress.

Update — Rachel Steindel Burdin pointed me to her Speech Prosody 2016 paper with Joseph Tyler, "Epistemic and attitudinal meanings of rise and rise-plateau contours". She notes that

We did a couple of perceptual experiments, which found first, in a forced choice task, subjects reliably hear these rises-to-plateaus as signaling that speaker thinks the listeners already knows the items in the list, and second, subjects hear the plateaus as making the speaker sound condescending. As for the potential New York connection–I looked into Jewish English intonation for my dissertation (just completed, so still not really out anywhere yet), and found some evidence for increased use of these types of contours by older Jews in listing environments. So, I'd say it's definitely likely, at least to the extent that we want to connect Jewish English intonation to New York City intonation.

And she points out that

The contour was first described in a 1978 paper by Bob Ladd as a "stylized rise", and he said it was common in lists where the individual items were "non-informative"–one example he gave was school closings, where, if all or nearly all the schools in the area were closed due to snow, you could use that pattern instead of a rise, and the general message you would then be getting across is "all of the schools are closed", rather than "these particular schools are closed".

There's certainly a connection, though I think it remains unclear just what degrees of freedom are available in such patterns. Thus in the particular Trump example given above, the final levels are sometimes slightly falling and sometimes slightly rising, in ways that seem to matter; the relative height of the final levels also seems significant; and the level of the lower initial regions also seems to vary in a meaningful way.

Also, specific examples aside, what Bob Ladd called "stylized intonation" in 1978 was a broader and rather different concept. In the abstract of that paper, he wrote:

The English intonation often referred to as a calling contour — a stepping-sequence of two level tones — is not inherently associated with calling, but conveys the implication that an utterance is in some way stereotyped or stylized. Vivid and quite precise nuances can be accounted for by the abstract meaning 'stylized.' This meaning is not restricted to the stepping-down contour, but is a more general phenomenon: at least three contours ending in level pitch are 'stylized' modifications of 'plain' contours ending in rising or falling pitch.

I think Bob was wrong to claim that all final levels of the type under discussion are "stylized" in the same sense that the (essentially chanted) calling pattern is. And I think that Bob would agree with that assessment now.

In Cynthia McLemore's 1991 dissertation ("The Pragmatic Interpretation of English Intonation: Sorority Speech"), she observed the distribution of similar phrase-final level contours in a University of Texas sorority, and found that

the contour signals continuation, which can be interpreted with respect to textual structure, textual content, or along temporal or spatial dimensions, depending on the nature of a discourse and its situational context. In sorority culture, one use of the form is to indicate the continuity of traditional activities.

She suggests that a phrase final level differs from a final rise, which

can be interpreted as setting up an expectation of "more to come" … because it connects … In contrast, phrase-final levels don't connect intonational phrases … they simply continue … The distinction is subtle, and might be more clearly characterized as the distinction between "additive" and "sequential."

In the context of monologues in sorority event planning meetings, she found that

level intonation is used to mark continuation within sections of the discourse concerned with individual events on the written program; its use is interpreted as continuing corresponding units of textual structure and textual content. In this situation, phrase-final levels contrast with phrase-final rises in that they are used on items that are apparent from the written program ('given'), while rises are used to mark utterances whose textual content is about deviations from the program. The use of levels also contrasts with the use of falls in this discourse: the preference is for falls to introduce delineated items on the agenda, while levels mark continuation of the text about those items within sections.

One of the key ideas in McLemore's work is that intonational patterns combine a universal aspect (as "diagrammatic icons") with values that can emerge from community experience in a particular culture, a particular setting, and a particular context. That second set of issues has for the most part been neglected elsewhere in the recent literature. To some extent, the speech of individual politicians in various settings may offer a way to approach these kinds of variation in the distribution of prosodic patterns.

It also remains unclear to what extent prosodic patterns are "digital", in the sense discussed here last month ("Is language 'analog'?", 7/17/2016). As Dwight Bolinger asked in 1949 ("Intonation and Analysis", Word 5(3): 248-254):

Is English intonation susceptible of phonemic analysis? If not now, will it be so later? What kinship is there between tonal and phonemic events, and is there such a thing as a tonal segment?

In his conclusion, he cites H.O. Coleman's 1914 monograph Intonation and Emphasis:

One appreciates Coleman's words, as true now as they were thirty years ago, that "investigations hitherto have been deprived of much of their value through the inquirers' not going far enough afield (thus building up a theory on the few obvious examples that occur to one at the moment) or through their taking their examples from the connected language of books where the sentences are often altogether wanting in the variety found in conversational speech." For linguists who wish to be scientists there is only one scientific procedure: gather the facts first, then theorize about them.

And he ends with a list of 11 questions, which starts this way:

I venture to list at random a few of the questions answers to which, both in themselves and in suggesting other questions and so gradually broadening our grasp of intonation, may some day make a precise, logical schematization possible. I hasten to disclaim any desire for "looseness" in the treatment of intonation; each problem must be attacked with parsimony of assumptions and with all the tightness of reasoning at our command; in short, scientifically.

1. What are the peculiarities of intonation of social groups? We have observed that preachers, circus barkers, and professors favor certain modes; what are these modes?

2. What are noteworthy idiosyncracies? Actors reveal these, as do ordinary folk.

3. Are idiosyncrasies genuinely original, or do they represent only a favoring of one kind of standard intonation over another, as when one person will say "so help me" and another "you betcha"?

4. What social occasions elicit particular intonations? A tie-up of this sort is one of the objective tests of the semantics of intonation.

5. What intonations are not used in English? One method of answering this is to study the errors made by foreigners which make their speech seem unEnglish.

6. What intonations are favored with particular locutions? Though not especially in search of these myself, I have recorded them for always, and then some, how I love that man, I wouldn't know, in the first place, silly boy!, and others. It is hardly enough for the student of intonation to content himself with a handful of oddities (the "Ripley" approach, to quote Bernard Bloch); the record must be rounded out. This means going beyond the whimseys of yes, no, hello, and goodbye; and in syntax it means investigating a few other things besides sentence-final intonations.

7. What is the place of intonation in communicative behavior as a whole? Bloomfield has referred to intonation as "gesture-like." This is a promising hint that deserves to be followed up.

I wish that I could say that Coleman and Bolinger's appeals had been definitively answered. There were reasons in 1914 or 1949 or 1978 why it was hard to do what they asked — but we've run out of excuses.

Jarek Weckwerth said,

August 8, 2016 @ 12:20 pm

I think a very similar pattern would be usual in this kind of context in Polish (from whence a connection with NYC Jewish English is certainly not impossible). It feels natural enough to this native speaker of Polish that I would be interested to hear of IE languages where it isn't typical in this kind of situation.

[(myl) An excellent question. ]

BZ said,

August 8, 2016 @ 3:07 pm

To my ear and out of context it sounds like Trump is using a common mocking pattern where mocker is contrasting what the person is saying and how it's going to end badly. Something like "We're gonna use great *business leaders* to work with our *generals* — we're gonna make great *trade deals* and our economy will go to *crap* and our troops will get *murdered*". In fact, depending on your political leanings, the trade deals with China part is already describing a negative outcome.

L.L. Sackman said,

August 13, 2016 @ 4:59 pm

Always nice to see prosody research, but you're too obsessed with trump for your own good.