Nick Clegg and the Word Gap

« previous post | next post »

Yesterday, Nick Clegg made news in England by announcing a new spending program ("Clegg unveils 'fairness premium'", ePolitix.com 10/15/2010):

Deputy prime minister Nick Clegg has unveiled a £7bn 'fairness premium' to help disadvantaged children through the education system.

The plan, to be included in the comprehensive spending review, will contain an offer of 15 free hours of pre-school education a week to two year olds from poorer families in England.

In a speech at a junior school in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, Clegg also confirmed the Lib Dem pledge of a "pupil premium" while they are at schools, and a new "student premium" to help them through university.

In his speech, Clegg gave some numbers from a widely-cited developmental study (Nick Clegg, "Putting a premium on fairness", Speech delivered at Spires Junior School, Chesterfield):

So, to summarise what we mean by fairness, fairness demands:

– that children and young people have a good start in life

– that the state plays a significant role in leveling the playing field for the next generation; and

– that patterns of inequality in one generation should not be automatically replicated in the next.

Against this benchmark – fairness as life chances – Britain does not fare well, as the recent report from the Equality and Human Rights Commission demonstrated.

By the time they hang up their coats for their first day at school, bright children from poor backgrounds have fallen behind children from affluent homes. Children from poor homes hear 616 words spoken an hour, on average, compared to 2,153 words an hour in richer homes. By the age of three, that amounts to a cumulative gap of 30 million words.

The FactCheck Blog at Channel 4 News pounced on these striking and specific numerical references. They certainly deserves scrutiny — though ironically, FactCheck's own discussion features a couple of careless errors. Nitpicking aside, however, there are some interesting and important issues here.

Cathy Newman at the FactCheck blog focused especially on Clegg's overall word-gap estimate (FactCheck: Nick Clegg's word count", Channel 4 News, 10/15/2010):

30 million struck FactCheck as a big ‘word gap’, and we wondered where he’d got it from.

The Cabinet Office told us it came from the book "Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children." So, the DPM was actually talking about the educational opportunities of kids across the Atlantic. And a quick flick through the book reveals it's actually based on a sample of just 42 American children – and that the research was undertaken in the 1980s. The book was published in 1995, by Dr Betty Hart and Dr. Todd Risley, with a forward from Lois Bloom at Columbia University in New York. FactCheck reached the now retired Lois Bloom, who confirmed the research was old, and that it showed income wasn't the only that determining factor in children's development. "The book says there are many other factors," she said "including how many people in the house work and how many children there are in the house."

So, it doesn't seem all that 'fair' to us, to pass off research that is 20 years old, and based on a small sample in America, as relevant to a speech about inequality in modern Britain.

In fact, the sample-size difficulty is worse than that. It's true that the study detailed in Hart & Risely's book ("Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children", 1995) involved "42 American children", as this abstract at eric.ed.gov explains:

Noting the scientifically substantiated link between children's early family experience and their later intellectual growth, this book describes a longitudinal study of the circumstances of early language learning and the central role of home and family in the emergence of language and word learning. The vocabularies of 42 children were studied from the time they first began to say words at about 1 year until they were about 3 years old. The study also observed the children's interactions with other persons in their families which formed the contexts for their word learning. Results indicated that the most important factors to language acquisition are the economic advantages of children's homes and the frequency of language experiences. The basic findings from the study are that children who were born into homes with fewer economic resources learn fewer words, have fewer experiences with words in interactions with other persons, and acquire a vocabulary of words more slowly. Five parenting features that predicted future achievement were: (1) language diversity; (2) feedback; (3) guidance style; (4) language emphasis; and (5) responsiveness. The book concludes by outlining an agenda for intervention that would begin in the home and very early in a young child's life, with a focus on the social influences on language and its acquisition within the cultural context of the family.

But those 42 children were divided into four sub-groups — and Clegg's statistics came from the top and bottom of the four groups. I took a look at the Hart and Risely study a few years ago ("Word counts", 11/28/2006), and quoted them giving further details about their sample:

Our final sample consisted of 42 families who remained in the study from beginning to end. From each of these families, we have almost 2 1/2 years or more of sequential monthly hour-long observations. On the basis of occupation, 13 of the families were upper socioeconomic status (SES), 10 were middle SES, 13 were lower SES, and six were on welfare.

The 30-million-word gap that Clegg cited was calculated from a comparison of data from the 13 upper SES ("professional") families with data from the 6 welfare families. (For details, see Betty Hart and Todd Risely, "The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3", American Educator, Spring 2003). The small and perhaps unrepresentative sample is an issue here — though as we'll see, it turns out that their vocabulary-growth comparisons are similar to those found in much larger and more representative samples.

But the more important problem, in my view, is Clegg's equivocation about which groups are being compared. His speech gives the impression that he's comparing those above and below a "poverty line" defining eligibility for his proposed remedies. But the numbers that he cites compare children from "professional" families with children from "welfare" families.

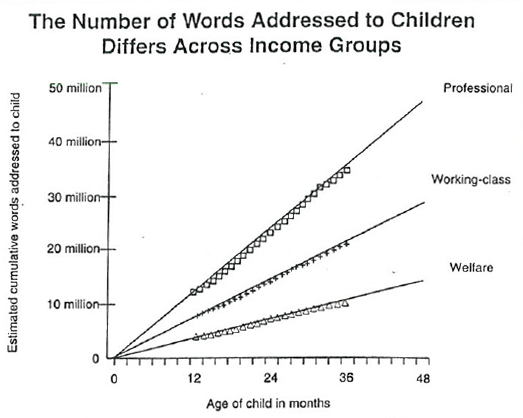

Unsurprisingly, Hart and Risely found that "working-class" families were in between the professional and the welfare families — and by most of their measures, closer to the welfare families. Here's their graph of the word-count data:

Cathy Newman at the FactCheck blog suggested that data from a different study would have been more relevant — and in doing so, she uncritically adopts a natural interpretation of Clegg's distinction between "children from poor backgrounds" and "children from affluent homes", namely that it refers to children below and above the poverty line:

But what about the Institute of Education's longitudinal study on 15,590 families of children born in Britain in 2000-2? In 2007, they found that three year old children from families living below the poverty line have a vocabulary on average 5 months behind those families living above the poverty line. With a large sample, and based in the UK, that research would seem to be more relevant.

It's true Clegg would have done better to cite vocabulary-development data from that Millennium Cohort Study — the sample is MUCH larger, is much more representative, comes from Britain, and is more recent. But the first problem with the FactCheck citation is that Newman didn't read the footnotes in the press release that she links to, and thus gets the number wrong.

Here's the press release (Centre for Longitudinal Studies, "Disadvantaged children up to a year behind by the age of three", Press Release 6/11/2007):

Vocabulary scores achieved by more than 12,000 children revealed that the sons and daughters of graduates were 101 months ahead of those with the least-educated parents. A second "school readiness" assessment measuring understanding of colours, letters, numbers, sizes and shapes that was given to more than 11,500 three-year-olds found an even wider gap – 122 months – between the two groups. The equivalent gaps for children in families living above and below the poverty line used by the researchers were five3 months for vocabulary and 104 months for school readiness.

As expected, girls did better than boys on average. They were three months ahead on both measures. Less predictably, Scots children were three5 months ahead of the UK average in their language development and two months ahead in "school readiness".

Why the footnotes? Well, the press release was amended on July 23, 2007, and for some reason the updates were implemented by means of superscript numbers and a note at the bottom of the page observing that

Further analysis of the data, carried out after this press release was issued, has caused us to revise some of these statistics. The correct figures are:

1 12 months

2 13 months

3 8 months

4 9 months

5 2 months

In other words, Newman's FactCheck post should have given 8 months, not 5 months, as the lag in vocabulary development for children from families below as opposed to above the poverty line.

But a comparison more comparable to Clegg's would have cited the fact that "sons and daughters of [college?] graduates" were 12 months ahead in vocabulary development compared with "those with the least educated parents", and 13 months ahead in a "school readiness assessment".

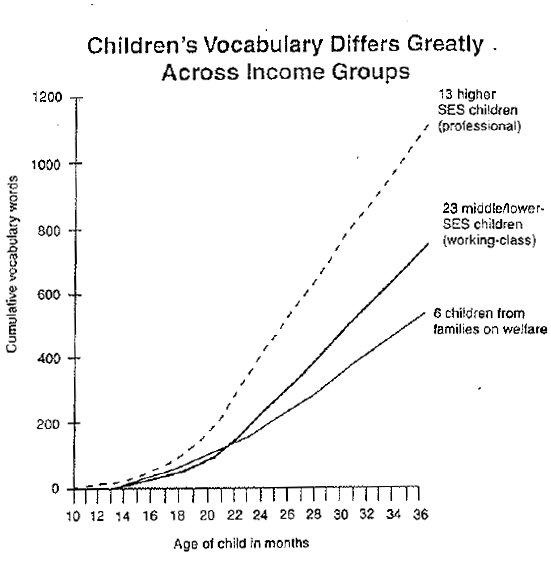

A 12- or 13-month gap at the age of three is considerable, in proportional terms. And if we compare these numbers from the Millennium Cohort Study to Hart & Risely's average vocabulary measurements by SES, as shown in the graph below, the results are quite similar — the average vocabulary of Hart & Risely's low-SES children lags about a year behind the average vocabulary of their high-SES children:

Again, though, note that the middle-SES children are in the middle — and somewhat closer to the children from families on welfare. This underlines, in my view, an important problem with programs of the sort that Clegg proposed. These programs aim to ensure "that patterns of inequality in one generation should not be automatically replicated in the next". But even if they have exactly the advertised effect, they only address one aspect of the phenomenon of inter-generational transfer of cultural capital — and they risk alienating the "middle/lower-middle SES" groups who may find themselves increasingly excluded from educational opportunities. (In the U.S., at least, it's clear that this "exclusion of the middle" is a growing problem.)

This is not an argument against remediation programs for children of the poorest families (Clegg's proposal targets the bottom 20% of the income distribution, according to Simon Baker, "Poor students to benefit from Clegg’s £7bn ‘fairness premium’", Times Higher Education 10/15/2010). But we should discuss the issues in a broader context.

For more background on the Millennium Cohort Study, see Kirstine Hansen and Heather Joshi, "Millenium Cohort Study (Second Survey): A User's Guide to Initial Findings", July 2007. This study is by no means only about SES and vocabulary development — for example, it provided evidence that occasional drinking by pregnant women probably isn't harmful after all, as reported in Lisa Belkin, "Drinking While Pregnant", NYT 10/6/2010.

Some other relevant LL posts about word counts, vocabulary development, and rates of vocabulary display: "Gabby guys: The effect size", 9/23/2006 (note especially the discussion of Martha Farah et al., "Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development", Brain Research 1110(1) 166-174, September 2006); "Word counts", 11/28/2006; "Cultural specificity and universal values", 12/22/2006; "Vicky Pollard's revenge", 1/2/2007.

Twitter Trackbacks for Language Log » Nick Clegg and the Word Gap [upenn.edu] on Topsy.com said,

October 16, 2010 @ 9:53 am

[…] Language Log » Nick Clegg and the Word Gap languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2712 – view page – cached October 16, 2010 @ 9:30 am · Filed by Mark Liberman under Language and culture, Language and politics Tweets about this link […]

Jarek Weckwerth said,

October 16, 2010 @ 10:25 am

This is in quite interesting for a completely non-linguistic reason: The announcement comes almost at the same time as the news of drastic fee increases and other draconic cuts at English universities (to keep to Channel 4 News, here's a link… Will this prevent the LibDems from sinking?

The Ridger said,

October 16, 2010 @ 11:07 am

Is "words addressed to children" really that crucial? I would have thought it was 'words children hear/are exposed to" that was the most important. (Obviously, if nobody ever speaks to the child, that's bad, but lots of people don't talk much to infants or children too young to talk back.)

[(myl) In my understanding, the evidence suggests that (for example) the value for vocabulary growth of words heard on television is much smaller than words exchanged in live conversation. And small children are likely to tune out of much inter-adult conversation. But in any event, a crucial issue in this area is the nature/nurture question. Partisans of the Bell Curve perspective will argue that the correlation between SES and vocabulary development is due to genetic factors. On this view, poor people have a lower verbal IQ for genetic reasons — it's part of the reason that they're poor — and their children inherit this characteristic, and display it in their rate of vocabulary development. So as I understand it, one of the points of the Hart & Risely study was not to argue that the number of words addressed to the child is the only relevant factor — on the contrary — but to suggest that there are some plausible factors on the nurture as opposed to nature side of the equation.]

And I wonder how much of the difference is because of words and how much is because of leisure time to spend playing with small children?

[(myl) Read their presentation of their study, especially Chapter 4, and you'll find out.]

Henning Makholm said,

October 16, 2010 @ 11:49 am

I think it is an immediate red flag that the first graph plots a single number of words for each socioeconomic group for each age point. An average over all children in the group? There should at least be variance bars.

[(myl) With N=6?]

Peter Taylor said,

October 16, 2010 @ 12:49 pm

It's from a British source (and a British university source at that) so it means university graduates, and I strongly suspect that if you asked the author whether that was the intended meaning they would reply along the lines of "What else could it mean?"

Clayton Burns said,

October 16, 2010 @ 2:31 pm

Perhaps we could abstract some language from this thoughtful post so as to access some of the assumptions:

–30 million struck FactCheck as a big ‘word gap’… later intellectual growth… children who were born into homes with fewer economic resources learn fewer words, have fewer experiences with words in interactions with other persons, and acquire a vocabulary of words more slowly–

–social influences on language and its acquisition–

—LL posts about word counts, vocabulary development, and rates of vocabulary display… "Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development"–

From these extracts, it seems as if there could be a raw measure of vocabulary development that would be more or less routine across studies.

That I deny. We are mixing "word gap," "intellectual growth," "learning words," "social vocabulary," "vocabulary acquisition," "vocabulary development," "vocabulary display," and "cognitive development" as if these concepts were transparent and non-problematic in terms of measurement.

[(myl) In fairness to the authors of these studies, you should look into their methods more thoroughly than just by making a list of sentence fragments from this post. In fact there are measures of all of these concepts that can be compared across studies; and in any case, the conclusions in each case are drawn from within-study comparisons.]

If the most important measure is language sensitivity, then we might ask how successfully students could master the new Arden "Hamlet," a casebook on the archaic elements in the play, the COBUILD English Grammar, and the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Sensitivity to multiple meanings, as in "contrived," would be a key measure.

[(myl) Um, we're talking about two- and three-year-old children. Did you read the post while accumulating that list of fragments?]

Is it realistic to have as our target the ability to read Kant? Perhaps not. But with recursive programs in Shakespeare (involving studying the Oxford School "Hamlet" in Grade 9 and the Arden "Hamlet" in Grade 12, along with the best corpus tools in Linguistics throughout high school), we could set realistic goals. Any system that purports to measure "intellectual growth" or "neurocognitive development" without such clear targets will create a mirage of data.

[(myl) It's reasonable to ask about reading Kant or Shakespeare — or a daily newspaper — but it seems quite strange to claim that there's no way to get a profile of cognitive abilities independent of doing particular things with particular authors.]

We are all familiar with educational "churning" whereby it seems to us as if advances are being made in New York or in the UK, only for us to see the numbers drift so that the trends of educational reform again turn out to be inconclusive. (A good informal corpus to assess word uptake is the editorials in the student media in America. I do not find the vocabulary use to be especially impressive).

What is even weaker in this student media corpus is sentence structure. In fact, my student who was most praised at university for his sentences worked obsessively with the COBUILD guide on report verbs, writing sentence after sentence out of his own experience, composition based on the verb lists in the guide. It is more important to be able to write high quality sentences (clearly meaning that you have a decent vocabulary) than to be able to display a lot of half-digested words, a common American elite university pathology. The SAT flash card disease.

[(myl) Again, I'm afraid that you're talking about things with little direct connection to the issues under discussion. The studies featured in this post dealt with 2- and 3-year-old children, for whom vocabulary development is an important measure and a reasonable proxy for other verbal abilities. The SATs are more than a dozen years off for them, and none of the kids studied by Hart and Risely were being taught by flash cards. The same studies also measured many other aspects of children's environment and achievement — I focused on vocabulary because it was what Clegg (and the FactCheck blog) cited.

Martha Farah's study, which I mentioned in passing at the end of the post — and which you also apparently didn't look at — did deal with 10-to-12-year-olds, but measured nine general cognitive areas, most with several sub-tasks, and most unconnected to language (e.g. mental rotation, shape detection, face perception, spatial working memory, etc.). The linguistic tasks included a "test of reception of grammar" as well as the Peabody picture vocabulary test, and the relevant result was that the effect size of the group differences for the linguistic tasks was much larger than it was for the other tasks.]

Poverty is a state of mind as well as a circumstance of economic deprivation. Here is one of the areas where the manifest failures of educational psychology should be addressed. In a concrete and tactile way. Helping in teaching memory and linguistic skills in an imaginative way.

dirk alan said,

October 16, 2010 @ 9:08 pm

if the goal is to have everyone be as smart as possible then why put a tax on it. education should pay students to learn – reward excellence. if society wants smart people there should be olympic style competition for the biggest fastest brains. easy peasy.

Uly said,

October 16, 2010 @ 9:36 pm

"(Obviously, if nobody ever speaks to the child, that's bad, but lots of people don't talk much to infants or children too young to talk back.)"

But a lot of people – particularly the people with the luxury to read about this sort of thing and to spend this sort of time with their kids – DO. They worry a lot about whether they're responding appropriately to their childrens' babbles. They talk about how they feel "silly" talking constantly to their children with a running narrative ("Here we go, we're walking down the street now. Wow, it's bumpy! Bumpy, bumpy, bumpy! And OVER the curb and across the street and UP again! Do you see that doggy? It's a big doggy, isn't it? Can you say doggy?") but that they do it anyway because "I know how good it is for them". They make the effort to learn some ASL signs so they can sign to their children as they speak in the hopes that it'll improve early communication skills.

There are more people than you think making a BIG effort at talking to their babies.

David said,

October 17, 2010 @ 7:53 am

Has the UK adopted the US definition of billion?

Leo said,

October 17, 2010 @ 12:05 pm

David: if by "the US definition of billion" you mean a thousand millions – i.e. 1,000,000,000 – then the UK adopted it a long time ago.

Teddy said,

October 17, 2010 @ 9:04 pm

To a young child/infant trying to parse the world of words, the task becomes markedly more complicated when the adult's speech goes unaltered. I actually teach kindergarten, and as long as children are still obviously acquiring language (and making plenty of mistakes), teachers–at least ones attune to the needs of the students–alter the way they speak. And with very young children, adults' speech is careful, intonation-ful, and, additionally, the interaction is replete with many non-verbal cues. (I'm sure any parent can attest to this.) I think the value of all of these aspects cannot be forgotten, and I think they also explain why inter-adult speech is not the best source of linguistic evidence for young children (those under 3).

I very much appreciate this post. I think it nicely shows how educational inequality cannot really be solved by throwing money at people of the lowest SES–something I by no means oppose.

dan said,

October 18, 2010 @ 4:07 am

As Jareck Weckwerth pointed out above, the Tory coalition is about to impose massive cuts on universities here, so it's clear what their policy is for closing the "word gap": make sure fewer students get to university, then there will be fewer *children* of university graduates to compare with working class and "welfare" kids. Gap closed and problem solved.

Of course you could also argue there's another "word gap", the one between the Lib Dems' manifesto commitment to scrapping tuition fees and their craven behaviour now in government, but I suppose that's not really a linguistic point.

Ginger Yellow said,

October 18, 2010 @ 6:43 am

"It's from a British source (and a British university source at that) so it means university graduates, and I strongly suspect that if you asked the author whether that was the intended meaning they would reply along the lines of "What else could it mean?""

OK, I'll bite. What else could it mean?

Anon said,

October 18, 2010 @ 7:16 am

@Ginger Yellow

I believe that in some crazy, messed-up countries one 'graduates' from a secondary educational institution known as a 'high school'.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secondary_education_in_the_United_States#Graduation_examinations

[(myl) One can also graduate from middle school (after 8th grade) and so on, down to kindergarten graduation.]

Clayton Burns said,

October 18, 2010 @ 1:39 pm

Mark: Here is the context for my comments:

[Deputy prime minister Nick Clegg has unveiled a £7bn 'fairness premium' to help disadvantaged children through the education system.

The plan, to be included in the comprehensive spending review, will contain an offer of 15 free hours of pre-school education a week to two year olds from poorer families in England.

In a speech at a junior school in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, Clegg also confirmed the Lib Dem pledge of a "pupil premium" while they are at schools, and a new "student premium" to help them through university.]

The context of my post is obviously the trajectory of learning though to university. Before posting my comment, I checked it to see that what I was saying was explicit. I should have anticipated your misreading and made everything far more explicit, telling you very carefully that by targets I meant the ultimate context for studies. That is, the setting in which studies would be planned would involve explicit knowledge of targets in junior high, high school, and university. I am not sure how you could disagree. If you were reading my text with attention.

However, what you say is not especially important. After working through a comprehensive news cycle this morning, I came to your site at the very last, with no sense of anticipation.

I do not expect anything from you except silly objections and deletion of comments. Your behavior is a genuine reflection of your character.

You cannot say that I have failed to be patient in assessing your performance. You should stop blogging for a period of reflection. You should stop abusing the UPenn name. You should stop interrupting posts by your readers. If you don't like the posts, just delete them in your rude way. Otherwise, please wait your turn to comment at the end of what someone else has said.

There is no need to highlight your comments. If I feel like reading them, I will do so.

Clayton Burns said,

October 18, 2010 @ 9:40 pm

This is supposed to be TROG-2 material, which may be relevant to native speakers of English only, if the source is correct. I might note that the materials seem to be very expensive for the work that went into them. Your comment in response to mine: ["Martha Farah's study, which I mentioned in passing at the end of the post… did deal with 10-to-12-year-olds… The linguistic tasks included a "test of reception of grammar"… and the relevant result was that the effect size of the group differences for the linguistic tasks was much larger than it was for the other tasks.]" I would be willing to listen to your explanation of the "test of reception of grammar" in Farah. Here are the TROG-2 sentences (apparently):

* A = two elements e.g., The sheep is running.

* B = negative e.g., The man is not sitting.

* C = reversible in and on e.g., The cup is in the box.

* D = three elements e.g., The girl pushes the box.

* E = reversible SVO e.g., The cat is looking at the boy.

* F = four elements e.g., The horse sees the cup and the book.

* G = relative clause in subjects e.g., The book that is red is on the pencil.

* H = not only X but also Y e.g., The pencil is not only long but also red.

* I = reversible above and below e.g., The flower is above the duck.

* J = comparative/absolute e.g., The duck is bigger than the ball.

* K = reversible passive e.g., The cow is chased by the girl.

* L = zero anaphor e.g., The book is on the scarf and is blue.

* M = pronoun gender/number e.g., They are carrying him.

* N = pronoun binding e.g., The man sees that the boy is pointing at him.

* O = neither nor e.g., The girl is neither pointing nor running.

* P = X but not Y e.g., The cup but not the fork is red.

* Q = postmodified subject e.g., The elephant pushing the boy is big.

* R = singular/plural inflection e.g., The cows are under the tree.

* S = relative clause in object e.g., The cup is in the box that is red.

* T = centre-embedded sentence e.g., The sheep the girl looks at is running. [End].

The age of 12 is critically important for grammar learning (or 11-13 depending on the student). I can't see how such a test could be run independently of the actual grammar being taught in the schools, which turns out in every case in British Columbia to be completely inept. (One of the worst offenders in the production of trash grammars is Pearson. That does not mean that the TROG-2 materials are junk, obviously, since the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, for example, is excellent).

I am not impressed with the above TROG-2 sentences. We could say that they are just meant to be functional. But I would want to know much more about the administration of these sentences.

Catching up despite divided time « 2 Languages 2 Worlds said,

November 7, 2010 @ 10:36 am

[…] article in the El Paso Times along with the post in language log on word gaps by SES brought to mind arguments about teaching English as a second language and the assumption that more […]