Irish DNA and Indo-European origins

« previous post | next post »

"Scientists sequence first ancient Irish human genomes", Press Release from Trinity College Dublin:

A team of geneticists from Trinity College Dublin and archaeologists from Queen's University Belfast has sequenced the first genomes from ancient Irish humans, and the information buried within is already answering pivotal questions about the origins of Ireland's people and their culture.

The team sequenced the genome of an early farmer woman, who lived near Belfast some 5,200 years ago, and those of three men from a later period, around 4,000 years ago in the Bronze Age, after the introduction of metalworking. […]

These ancient Irish genomes each show unequivocal evidence for massive migration. The early farmer has a majority ancestry originating ultimately in the Middle East, where agriculture was invented. The Bronze Age genomes are different again with about a third of their ancestry coming from ancient sources in the Pontic Steppe.

"There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island," said Professor of Population Genetics in Trinity College Dublin, Dan Bradley, who led the study, "and this degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues."

The paper is Lara M. Cassidy et al., "Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome", PNAS 2015:

Modern Europe has been shaped by two episodes in prehistory, the advent of agriculture and later metallurgy. These innovations brought not only massive cultural change but also, in certain parts of the continent, a change in genetic structure. The manner in which these transitions affected the islands of Ireland and Britain on the northwestern edge of the continent remains the subject of debate. The first ancient whole genomes from Ireland, including two at high coverage, demonstrate that large-scale genetic shifts accompanied both transitions. We also observe a strong signal of continuity between modern day Irish populations and the Bronze Age individuals, one of whom is a carrier for the C282Y hemochromatosis mutation, which has its highest frequencies in Ireland today.

This is presented as support for the Pontic-Caspian Steppes theory of Indo-European origins:

Three Bronze Age individuals from Rathlin Island (2026–1534 cal BC), including one high coverage (10.5×) genome, showed substantial Steppe genetic heritage indicating that the European population upheavals of the third millennium manifested all of the way from southern Siberia to the western ocean. This turnover invites the possibility of accompanying introduction of Indo-European, perhaps early Celtic, language. Irish Bronze Age haplotypic similarity is strongest within modern Irish, Scottish, and Welsh populations, and several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland appear at this horizon. These include those coding for lactase persistence, blue eye color, Y chromosome R1b haplotypes, and the hemochromatosis C282Y allele; to our knowledge, the first detection of a known Mendelian disease variant in prehistory.

See David W. Anthony and Don Ringe, "The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives", Annual Review of Linguistics 2015, for further arguments in favor of this view.

For the contrary position, see Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson, "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin", Nature 2003.

For a review of the previous state of the genetic evidence, see Pedro Soares et al., "The Archeogenetics of Europe", Current Biology 2010:

The question of the spread of the Neolithic became intertwined with that of the dispersal of the Indo-European languages, as a result of Renfrew's proposal that the Proto-Indo-European language spread from Anatolia with early farming. This hypothesis has become less plausible in the light of the mtDNA and Y-chromosome evidence as well as archaeological and linguistic criticisms. Although computational analyses of lexical data have been cited in its support, historical linguists find such analyses unpersuasive because of the unreliability of word-lists (especially due to borrowing) and because the approach ignores the strong likelihood of convergence and underestimates the rate of language change. The implied reinstatement of glottochronology — dating language splits — has also failed to win backing from linguists, and there has been widespread scepticism as to whether archaeology and linguistics can be combined so readily. Paraphrasing Kohl, conflating language, culture and genetics is the “cardinal sin” of molecular anthropology. If any consensus remains, it is probably that if there is any single explanation to be found for the spread of Indo-European, it is more likely to lie with the next major change to reshape Europe in the wake of a continent-wide system collapse. Possibly incurred by climatic changes c. 6 kya, this culminated in Sherratt's “secondary products revolution” of the 3rd millennium BC, when a number of agricultural innovations, including wool, the plough, the horse and wheeled vehicles, were introduced and spread within Europe 118, 124, 125, 126 and 127. This is, however, a time window little explored by archaeogeneticists to date.

So if I understand the impact of these new findings, they verify that "Bronze age individuals" from County Antrim, 3500-4000 years ago, had both "substantial Steppe genetic heritage" as well as "several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland". While this doesn't prove that IE languages were brought to the western edge of Europe by Bronze-age migrants from the steppes rather than earlier agriculturists from the middle east, at least it shows that some (descendants of) steppe immigrants were there at the right time, and that their progeny remain prominently represented in the current Irish gene pool.

The critical question for the study's authors seems to be diffusion vs. displacement:

Twentieth-century archaeology was dominated by two nonmutually-exclusive paradigms for how such large scale social change occurs. The first, demic diffusion, linked archaeological change with the displacement and disruption of local populations by inward migrations. However, from the 1960s onwards, this assertion was challenged by a paradigm of cultural diffusion whereby social change happened largely through indigenous processes.

High-throughput sequencing has opened the possibility for genome-wide comparisons of genetic variation in ancient populations, which may be informatively set in the context of extensive modern data. In Europe, these clearly show population replacement by migrating farmers from southwest Asia at the onset of the Neolithic with some retrenchment of the earlier Mesolithic genome at later stages. Three longitudinal genome studies have also shown later genome-wide shifts around the beginnings of the Bronze Age in central Europe with substantial introgression originating with the Yamnaya steppe herders. However, replacement coupled to archaeological horizons is unlikely to be a universal phenomenon, and whether the islands of Britain and Ireland, residing at the temporal and geographical edges of both the Neolithic and steppe migrations, were subject to successive substantial population influxes remains an open and debated question. For example, a recent survey of archaeological opinion on the origins of agriculture in Ireland showed an even split between adoption and colonization as explanatory processes. Recent archaeological literature is also divided on the origins of the insular Bronze Age, with most opinion favoring incursion of only small numbers of technical specialists.

The genetic evidence from the "early farmer woman" seems to favor the diffusion side of the argument:

From examination of the fraction of her genome, which is under ROH, she seems similar to other ancient Neolithics, suggesting that she belonged to a large outbreeding population. This analysis argues against a marked population bottleneck in her ancestry, such as might have occurred had she been descended from a small pioneering group of migrating farmers. Either a restricted colonization does not reflect the nature of the first Irish farmers or her ancestry was augmented by substantial additional Neolithic communication from elsewhere in intervening centuries.

But the men from Rathlin Island seem to offer some evidence for displacement:

Thus, it is clear that the great wave of genomic change which swept from above the Black Sea into Europe around 3000 BC washed all of the way to the northeast shore of its most westerly island. At present, the Beaker culture is the most probable archaeological vector of this Steppe ancestry into Ireland from the continent, although further sampling from Beaker burials across western Europe will be necessary to confirm this. The extent of this change, which we estimate at roughly a third of Irish Bronze Age ancestry, opens the possibility of accompanying language change, perhaps the first introduction of Indo-European language ancestral to Irish. This assertion gains some support by the relative lack of affinity of non-Indo-European speakers, Basques, to the ancient Bronze Age genomes.

So on balance, a win for the Pontic Steppes.

Jonah Katz said,

January 1, 2016 @ 8:25 am

Worth pointing out that a more reasonable version of Atkinson et al.'s tree model supports the Pontic-Caspian hypothesis: http://www.linguisticsociety.org/sites/default/files/news/ChangEtAlPreprint.pdf

[(myl) Indeed — I should have included that, though it would have made an excessively long post even longer…]

J. W. Brewer said,

January 1, 2016 @ 12:08 pm

Why assume that a single individual is genetically representative of the median inhabitant of Ireland 5200 years ago rather than an outlier, or even that three individuals whose corpses were all found in the same location were representative of the median inhabitant of Ireland as a whole as of that later time period? At a minimum the lack of "steppe-associated" genes in the earlier individual is not inconsistent with the possibility that incomers with the steppe-associated genes were already in Ireland 5,200 years ago side-by-side with the descendants of earlier arrivals but there had not yet been sufficient exogamy-plus-time to distribute those genes throughout the whole population.

[(myl) All of that is certainly true. But with respect to the three guys from Rathlin Island, the claim is that (along with the "steppe-associated" variants) they have "several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland […] [including] those coding for lactase persistence, blue eye color, Y chromosome R1b haplotypes, and the hemochromatosis C282Y allele." The last of those, according to Wikipedia, is "most common among those of Northern European ancestry, in particular those of Celtic descent". So those three are plausibly part of the ancestral population of Celts, rather than some lost wanderers far from home.]

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 1:57 pm

The lack of samples for this paper, on key archaeological horizons that likely contributed to (or were closely related to) both the ancestors of those on:

1. Rathlin Island

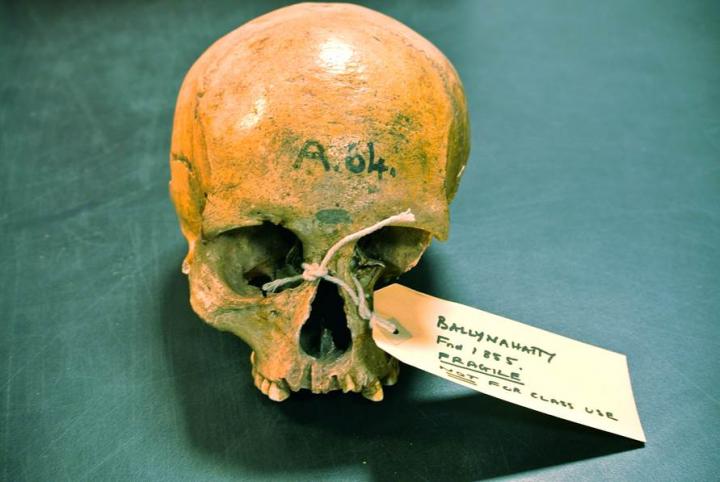

2. Ballynahatty

is a key weakness of this paper.

For the Rathlin Island samples, if you look in the supplemental data D statistics tables, you see that these samples compared most strongly with the Cardial early Neolithic, Yamnaya, Samara, Sintashta, German Bell Beaker, Halberstadt, Unetice, Alberstedt, Scandinavian hunter-gatherers, Hungarian Neolithic samples, and Loschbour (western European hunter gatherer), etc.

It's really a hodge podge that does not immediately suggest a Bronze Age Russian Steppe origin for these Rathlin Island samples. Archaeology doesn't suggest this either, at least according to the work of Terberger, Zhilin and Hartz. Their paper suggests a complex prehistory for the ancestors of Rathlin Island in which their upstream ancestors likely stem from Ertebolle, Narva and also Russian Steppe cultures (not necessarily in the Bronze Age).

http://www.quartaer.eu/pdfs/2010/2010_hartz.pdf

It is not clear that samples from the Funnelbeaker, Ertebolle or Narva culture were taken for this paper. I don't believe so.

Regarding the Neolithic-like sample (Ballynahatty), it should be said that most reasearches of the Neolithic today believe that the horizon for the Neolithic in Europe originates in Anatolia and the Aegean, *not* "the Middle East" proper. This is by no means a settled question. There is *no* ancient DNA from the Mesolithic for Southern Europe or Anatolia or the Levant, so it is virtually impossible to make any deductions, at this time, about the origin of Neolithic people.

The paper overstates what can be said about the origin of the Irish.

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:09 pm

> The genetic evidence from the "early farmer woman" seems to favor the diffusion side of the argument:

If you mean cultural, rather than demic diffusion, in fact it is the other way around. The paper is saying that, although this is just one sample from Ireland, genetically she seems to be part of a large population. So mass migration into Ireland by early farmers is favoured, rather than a small group of incomers from whom the local hunter-gatherers learned farming. She resembles Neolithic samples from the European continent.

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:15 pm

Having just carefully checked the samples used in the paper for Northern Europe, I have confirmed that the Rathlin Island samples were not compared against samples representing the Ertebolle or Funnelbeaker culture.

These are at least as likely sources for Rathlin Island people as the Bronze Age Russian Steppe.

Again, "conclusions" for this paper are misleading and overstated.

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:22 pm

This paper and other ancient DNA papers last year favoured the Steppe homeland of IE, but not by eliminating the possibility of Neolithic migration. Quite the contrary. The recent research from ancient DNA has provided conclusive proof that farming was brought to Europe by farmers from the Near East. We can imagine that these farmers also brought languages new to Europe. They just were not IE.

We have fragments of some European Neolithic languages in substrate. See for example Kroonen, G. 2012. Non-Indo-European root nouns in Germanic: Evidence in support of the Agricultural Substrate Hypothesis, in A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe (Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 266), R. Grünthal and P. Kallio (eds.), 239-60. Helsinki.

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:33 pm

> the Ertebolle or Funnelbeaker culture. These are at least as likely sources for Rathlin Island people as the Bronze Age Russian Steppe.

Not remotely likely. Ertebolle was a Mesolithic culture which never reached the British Isles.

Funnelbeaker/TRB was a late Neolithic Culture from which we have DNA samples, which show it to be typically Neolithic, like the Irish Neolithic woman from Ballynahatty. One such sample – Gok2 – was included in the Cassidy 2015 paper for comparison. I quote:

D and f statistics support identification of Ballynahatty with other MN samples who show a majority ancestry from Near Eastern migration but with some western Mesolithic introgression. Outgroup f3 statistics indicated that Ballynahatty shared most genetic drift with other Neolithic samples with maximum scores observed for Spanish Middle, Epicardial, and Cardial Neolithic populations, and the Scandinavian individual Gok2.

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:40 pm

@Jean Manco

"This paper and other ancient DNA papers last year favoured the Steppe homeland of IE, but not by eliminating the possibility of Neolithic migration. Quite the contrary. The recent research from ancient DNA has provided conclusive proof that farming was brought to Europe by farmers from the Near East."

The paper doesn't say "Near East". It says "Middle East". There is a difference.

And in fact, according to this paper:

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822%2815%2901516-X

the Neolithic emerges in Anatolia.

If you look carefully at the autosomal data in this paper, it is clear that the Neolithic emerges not only in Anatolia, but also in what is today Bulgaria and Greece.

So the paper is incorrect when it states prominently in the abstract, that the origin for the Irish Neolithic is "the Middle East."

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 2:55 pm

@Jean Manco

"Ertebolle was a Mesolithic culture which never reached the British Isles. "

How do you know? The early archaeology of the British Isles is not that well understood. You are right that archaeological sites for Ertebolle are Northern European specific. But we won't know, if we don't test it against the Rathlin Island samples.

"Funnelbeaker/TRB was a late Neolithic Culture from which we have DNA samples, which show it to be typically Neolithic, like the Irish Neolithic woman from Ballynahatty. One such sample – Gok2 – was included in the Cassidy 2015 paper for comparison."

One sample? That's all. Funnelbeaker was a very complex archaeological horizon.

"D and f statistics support identification of Ballynahatty with other MN samples who show a majority ancestry from Near Eastern migration but with some western Mesolithic introgression. Outgroup f3 statistics indicated that Ballynahatty shared most genetic drift with other Neolithic samples with maximum scores observed for Spanish Middle, Epicardial, and Cardial Neolithic populations, and the Scandinavian individual Gok2."

I can read, Jean. I can also read the D stats results in the supplemental data. Rathin groups with Scandinavian hunter gatherers and Hungarian KO1 as much as it groups with Sintashta, Samara and Yamnaya. So you can't definitively say that Rathlin is from "Bronze Age Russian steppe herders" gold and copper smelters.

A bit of wishful thinking?

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 3:17 pm

> The paper doesn't say "Near East". It says "Middle East". There is a difference.

Not really. Near East is the term usually used by archaeologists, while Middle East is the one we hear on the news. The authors picked the term best known today. I tend to use Near East. It makes no difference to the origin of Western Eurasian farming, which scholars are agreed upon.

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 3:33 pm

@Jean Manco

"Not really. Near East is the term usually used by archaeologists, while Middle East is the one we hear on the news."

That's garbage, Jean. Anatolia is not in the Middle East.

Most of the DNA that is coming up with this European "Early Neolithic Farmer" ancestry from early Neolithic sites are from Kumtepe (the same site as Greek/Luwian Troy), and Greece. Kumtepe is hardly even in the "Near East", let alone the "Middle East".

Kumtepe, Troy, Istantanbul, the Dardanelles, Constantinople, Western Anatolia, whatever you want to call it, isn't even understood as being in the "Near East" proper. It's traditionally understood as being at the Gateway to the East.

"The authors picked the term best known today."

Perhaps the authors should consider their misleading language more carefully.

"I tend to use Near East. It makes no difference to the origin of Western Eurasian farming, which scholars are agreed upon."

It actually does make quite a big difference to a lot of people. It's quite convenient for you there in the UK, Jean, sitting on top of one of the biggest thefts of all time, the Parthenon Marbles, telling us all here that there is no difference between Greece and the "Middle East".

Go ahead, it's all very convenient for you to be expropriating Greek identity. Part of a long tradition.

Ask any Greek person: "Is Greece in the Middle East?" See what their answer is.

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 3:36 pm

> How do you know? The early archaeology of the British Isles is not that well understood. You are right that archaeological sites for Ertebolle are Northern European specific.

Indeed the Ertebolle culture is distinctive. It does not appear in the British Isles, the Mesolithic archaeology of which is actually quite well understood and has no pottery. Unlike Ertebolle which does. I think you may be misled by the pottery. The first pottery in Europe is the V-bottomed type which arrived in the middle Volga River valley by 7000 BC with hunter-gatherers from the Asian steppe. Thanks to recent ancient DNA papers, we now know that it arrived with a people new to Europe. Their descendants formed a key part of the Copper Age Yamnaya culture. Before that some of the forager pottery-makers had moved northwards to the Baltic and Scandinavia by about 5500 BC. One of the cultures they created was Ertebolle. It would be very interesting to get DNA samples from them. We may indeed find that they had something in common genetically with the steppe people. But they were not the originators of the Bell Beaker culture. That we know not only archaeologically from the Bell Beaker "package" of features closely resembling that of the Yamnaya, but gebetically because the Yamnaya were the product of a mixture between the incomers from the Asian steppe and locals including some carrying a genetic signature from the Mesolithic Caucasus. Bell Beaker people carry that Yamnaya mixture.

Jean Manco said,

January 4, 2016 @ 3:41 pm

>> It actually does make quite a big difference to a lot of people. It's quite convenient for you there in the UK, Jean, sitting on top of one of the biggest thefts of all time, the Parthenon Marbles, telling us all here that there is no difference between Greece and the "Middle East".

Did I say that? Greece is in Europe, as everyone knows. For Near East, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Near_East

Marnie Dunsmore said,

January 4, 2016 @ 4:04 pm

@Jean Manco

"Indeed the Ertebolle culture is distinctive. It does not appear in the British Isles, the Mesolithic archaeology of which is actually quite well understood and has no pottery. "

Jean, the Mesolithic of Britain is not well understood at all, especially in Scotland. New sites are turning up in Scotland all the time. For instance, this significant Hamburgian Havalte site was just excavated in the last five years:

http://www.lithicresearch.co.uk/scotlands.html

And there is some preliminary evidence for a Maglemosian in Scotland.

Nothing definitive here, but certainly enough evidence to beg for a consideration of a more complex model than invasions Bronze Age herders from Russia.

Genetically speaking, Ertebolle, Maglemosian, Funnelbeaker and other cultures could have looked quite similar.

" I think you may be misled by the pottery. The first pottery in Europe is the V-bottomed type which arrived in the middle Volga River valley by 7000 BC with hunter-gatherers from the Asian steppe. "

I'm not misled by the ceramics of the Funnelbeaker culture. The Funnelbeaker culture is a highly complex archaeological horizon that does not fit into neat classification.

"Thanks to recent ancient DNA papers, we now know that it arrived with a people new to Europe. Their descendants formed a key part of the Copper Age Yamnaya culture."

The D stats in the papers you are mentioning do not at all definitively indicate Yamnaya. Your own Dstats just as easily pick out, with equal likelihood, Scandinavian Hunter Gatherers, Samara Hunter Gatherers and Hungarian Hunter Gatherers, as they do Yamnaya.

"One of the cultures they created was Ertebolle. It would be very interesting to get DNA samples from them. We may indeed find that they had something in common genetically with the steppe people. "

That is what the Hartz, Terberger, Zhilin paper I posted suggests.

"But they were not the originators of the Bell Beaker culture. That we know not only archaeologically from the Bell Beaker "package" of features closely resembling that of the Yamnaya,"

Current archaeology does not indicate that the origin of the Bell Beaker Culture is known. And the Bell Beaker culture is very distinct from the Yamnaya culture, autosomally speaking.

"the Yamnaya were the product of a mixture between the incomers from the Asian steppe and locals including some carrying a genetic signature from the Mesolithic Caucasus. "

I'm sorry, Jean, but these kinds of deductions are appallingly amateurish.

From an autosomal DNA perspective, Yamnaya as a possible contributor to Bell Beaker is one of a virtually infinite set of possible contributors.