Tibetan –> Chinese –> Chinglish

« previous post | next post »

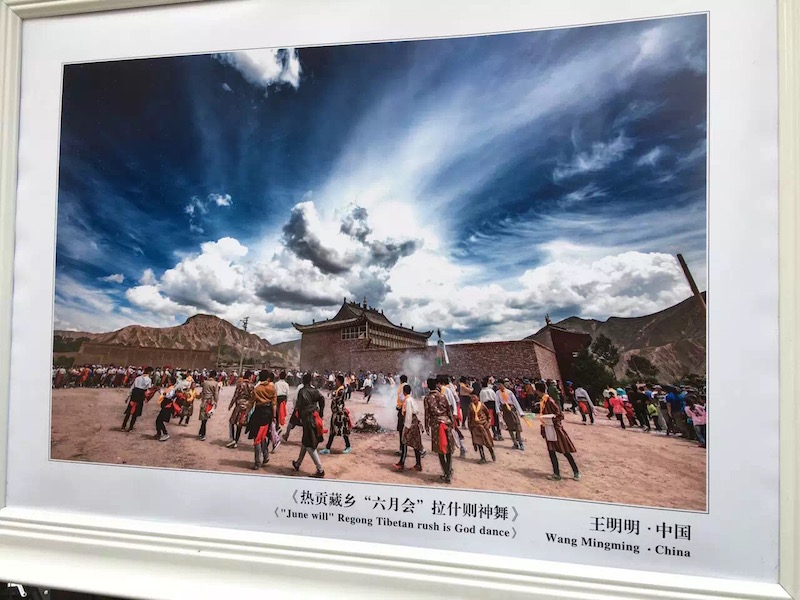

One of my graduate students sent me the following picture (click to embiggen):

The English translation of the title is a mess. Before trying to figure out what the original Tibetan references were, we need first to translate the Chinese more accurately:

Règòng Zàng xiāng 热贡藏乡 ("Regong Tibetan Township")

Liùyuè huì 六月会 ("June [or Sixth Month] festival")

Lāshízé shén wǔ 拉什则神舞 ("Lashize spirit dance")

Major mistakes:

1. translating "huì 会" ("meeting; festival; gathering") as "will" (a completely separate meaning for the character, which has dozens of different meanings)

2. mistranscribing "lāshí 拉什", which is part of the Chinese transcription of a Tibetan word, into English "rush"

3. mistranslating zé 则 as "is" when it should be part of the same word mentioned in item 2.

There are other, lesser mistakes that I won't spell out individually now, but which will emerge in the course of the discussion below.

The first two characters refer to the Tibetan place known to the Chinese as Tóngrén 同仁 county (Qinghai province), which the Tibetans call Repgong (reb gong), a well-known town in Amdo that has produced more than a few noted scholars. The 6th month is not June, but the Sixth Month of the lunar calendar when there is a celebration there called Luröl (glu rol ["music / song play"] — contested interpretations: lus rol ["body play"] and klu rol ["nāga play"]).

There has been a lot written on this performance (Lawrence Epstein has a piece in Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet; Charlene Makley and many others have also written about this event called Luröl, in which TIbetans insert pokers into their faces and there is an inversion of the roles of gods and demons (and institutionalized Buddhism with indigenous spirit rites), where lamas become antagonists for a few days in the theatrics as well. The "spirit dance" is probably referring to this.

See also:

Nicolas Sihlé, "Repkong rituals of offering to worldly deities" (3/28/12)

Lawrence Epstein and Peng Wenbin, "Ritual Ethnicity, and Generational Identity", in Melvyn C. Goldstein and Matthew Kapstein, "Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity", pp. 124-135.

Lāshízé shén wǔ 拉什则神舞 ("Lashize spirit dance") is more difficult to identify. Even Gedun Rabsal, who is actually from Reb-gong, puzzled a bit over this and finally thought Lashize was perhaps Lha-rtse (“heavenly”…). This might fit with the description here. It seems, however, that the proper term would be lha-rtsed ("entertain the gods", see Epstein and Peng, p. 132). This is the specific dance festival indicated by Lashize. These are performed by mediums who give voice to the “god’s speech” (lhake [lha-skad]).

To conclude this post with a brief look at the beautiful Tibetan script and a precise identification of where the ritual depicted here took place, two different sources in Rebgong confirmed that the picture is from Rusholma རུ་ཞོལ་མ་ village in Linggya གླིང་རྒྱ།.

[Thanks to Elliot Sperling, Gray Tuttle, Matthew Kapstein, Douglas Duckworth, Fangyi Cheng, Sonam Tsering, Pema Bhum, Gedun Rabsal, and several other Tibetan friends whom they contacted]

Victor Mair said,

November 12, 2015 @ 8:01 am

From Matthew Kapstein:

lus rol "body play" should no doubt be ruled out — it is not a homonym

with the other two,which are perfect homonyms in most dialects

cameron said,

November 12, 2015 @ 11:55 am

They "insert pokers into their faces and there is an inversion of the roles of gods and demons "? What larks!

Crane W. said,

November 12, 2015 @ 1:08 pm

Behind this is a subconscious cultural ignorance of Han Chinese. It never occurs to a lot people that Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian can and should be translated directly to English. And such things happen over and over and over.

Ngawa is transliterated to 阿坝, then again a translator – presumably Han Chinese who doesn't care to learn Tibetan and totally ignorant of the word “Ngawa” – renders it as Aba. And then, it's officially Aba.

Victor Mair said,

November 12, 2015 @ 1:16 pm

Yes, Crane W., and that's why we have Kashi instead of Kashgar, and thousands of other such truncated and severely distorted names.

Bmblbzzz said,

November 12, 2015 @ 2:39 pm

Translating through any intermediary language always results in distortion, for obvious reasons. When the political and cultural sensitivities are such as between Tibet and China that can only make things worse (or indeed, the practice of using Chinese as an intermediary language for translating Tibetan can only make relations between Tibet and China worse).

Ken Miner said,

November 12, 2015 @ 5:56 pm

click to embiggen

You guys – we don't need "embiggen", because we have "enlarge" – we need " versmallen" or whatever, which really does fill a niche. Linguists of the future! Arouse from your aesthetic slumber!

Matt said,

November 12, 2015 @ 7:28 pm

"A noble spirit enlarges the smallest man?" No, that sentence is far from cromulence in my judgment, and so the two words cannot be deemed interchangeable.

Crane, Victor – does it really never occur to them, though? I would be more inclined to attribute the effect to laziness (who wants to go looking for a direct translator?) and possibly wariness (putting Chinese in the middle helps ensure that nothing can slip through into the English that might "hurt the feelings" of any peoples), rather than ignorance of the possibility. Like, I don't think it's an accident when place names are filtered through Chinese rather than direct from the local language.

K Chang said,

November 15, 2015 @ 3:55 am

Question for Prof Mair, even though it is only peripherally related to Chinese…

There's a discussion over in reddit-land in /r/chineselanguage that "Chinese has no ontology" from a 1990's philosophy book.

https://www.reddit.com/r/ChineseLanguage/comments/3sv4ol/not_sure_if_theres_any_language_historians_here/

My first reaction is "WTF?!" then I decided to consult someone who may know the experts!

Ken Miner said,

November 15, 2015 @ 6:33 pm

Just to complete the record, I now see that "embiggen" has the same origin as "cromulent". The Simpsons. I don't have a TV so I don't know this stuff…

Kaleberg said,

November 16, 2015 @ 1:06 pm

I'm not sure about the sixth month not being June. Maybe not in this context, but there used to be a Chinese restaurant a few blocks from MIT in Cambridge called the fifth-month-flower. The owner intended it as a pun for Mayflower, a proper New England name for a Chinese restaurant.

Victor Mair said,

November 16, 2015 @ 10:56 pm

@Kaleberg

This is the Tibetan 6th month, not Chinese.

Victor Mair said,

November 16, 2015 @ 10:57 pm

From Robbie Barnett:

Regong is Rebgong, probably, but it's not a xiang. Nowadays it's used for the town and the county, called Tongren in Chinese, which is within in Malho (Huangnan) prefecture; it may be used for the larger area including Tsekho (Zeku) and Kawasumdo (Tongde) too in some cases. So maybe there is a xiang within it called Rebgong, which is the name by which Tibetans know the entire town/county? Or maybe Mr Wang or his translator just got this wrong? The most famous locality within Rebgong is Rongwo, where the major monastery of the area is located, but Rongwo would not become Regong in Chinese pronunciation. I don't remember offhand the names of the other xiang or of the urban neighbourhoods within the area.

The festival is the Lu rol festival. It is in the sixth month. Many foreign scholars have written papers on it, since it is not under the kind of restrictions that limit access to many other Tibetan areas – and of course because it is very interesting too. You can find a very detailed discussion by Solomon Rhino here.

Unfortunately, many Chinese tourists (and no doubt some non-Chinese) who see themselves as photographers, mostly men as far as I can tell, go there too and film ritual participants at extremely close range. It is very intrusive and offensive, and I don't know how Tibetans put up with it. I attach some photos of this in 2007, though I didn't capture anything like the most offensive cases. I also attach a photo of a similar incident in Xinjiang, from the French documentary "Forbidden Territory", which shows a sequence of tourists making Uighurs pose for their cameras in required positions and dress. There is a valuable HK website by a Chinese traveller called "December" in 2010 dedicated to exposing intrusive actions by tourists at 《轉帖》她在山坡上哭了—-拿相機的人,請你自重!http://forum.unwire.hk/thread-4230-1-1.html#.UheRHNKBmFB and mirrored at http://www.douban.com/note/147765317 (reproduced in English in part at http://www.tibetwatch.org/uploads/2/4/3/4/24348968/culture_clash_-_tourism_in_tibet.pdf.)

"Spirit dance" is not accurate, and usually in English, just the name "Lu rol" is used, without translation, which usefully skirts the translation problems. Literally the first element means "Naga" and the second can refer to play or game, and is cognate with compound terms meaning music, enjoyment, and delight. But I think there are some alternative spellings in the Tibetan, so the first term could mean or once have meant "song". Katia Buffetrille discusses this in her essay on the festival, "Le jeu rituel musical (glu/klu rol) du village de Sog ru (Reb gong) en A mdo" (The ritual musical game (glu/klu rol) of the village of Sog ru (Reb gong) in A mdo)," which is available at https://emscat.revues.org/508?lang=en.

[VHM: Robbie sent me a number of photographs showing Chinese men with big cameras walking right up to the dancers and poking the lenses at them. If anybody is really interested in seeing these photographs, I can send them to you.]