Devin, a newly discovered language

« previous post | next post »

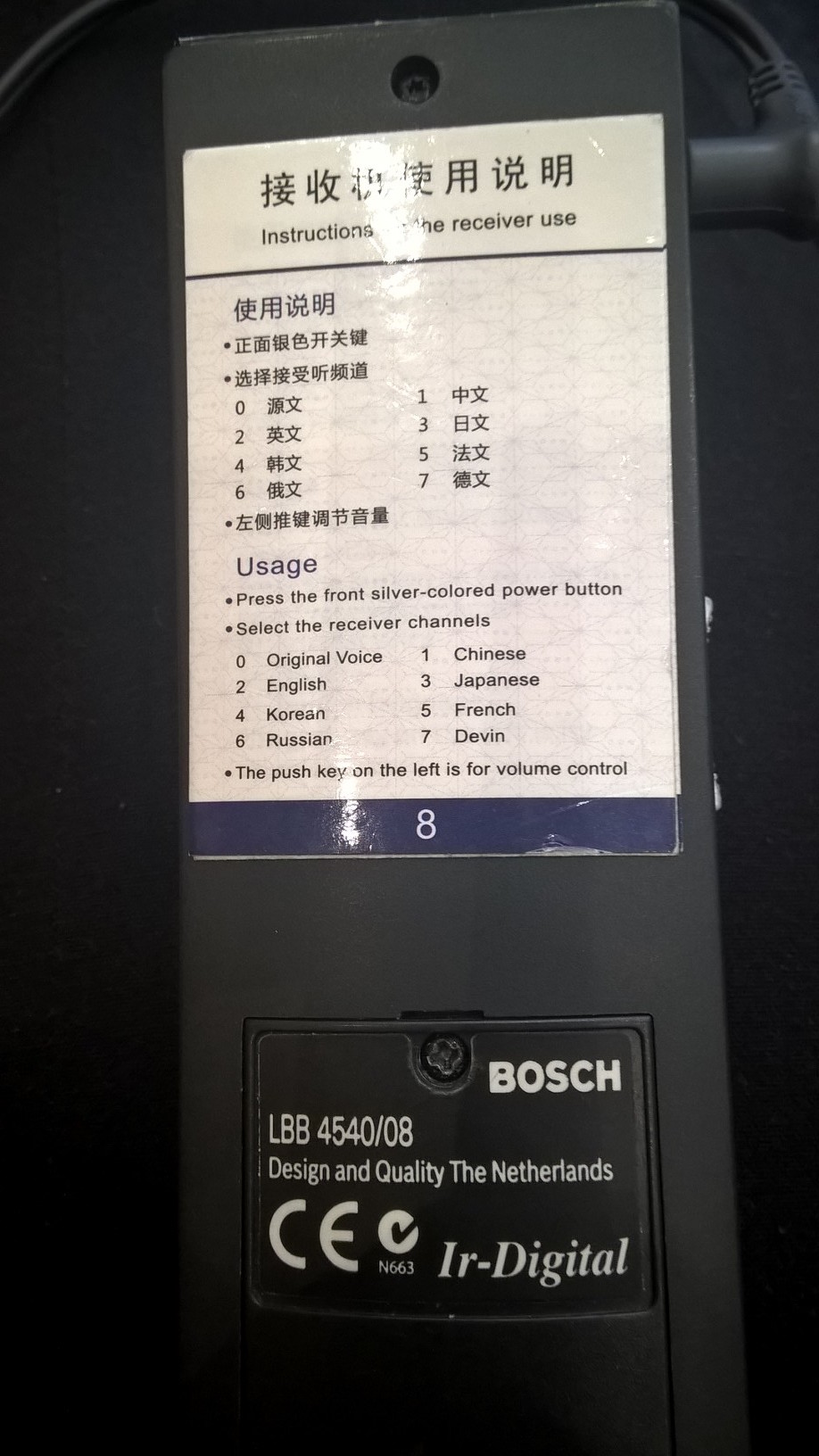

Jenny Chu sent me this photo of a simultaneous interpretation device she came across at an event in Shanghai today:

Look closely at language #7. In Chinese it is Déwén 德文 (i.e., "Deutsch language", where they lop off the latter part of the native name and replace it with wén 文 ("language") — Déwén 德文 is the usual Mandarin name for German. In the English list of language names, they have "Devin". That's obviously close to Mandarin "Déwén", yet not identical. "Devin" sounds like it could have been meant to represent the Shanghainese pronunciation of the word which has a voiced fricative initial for 文 instead of the voiced labio-velar approximant in Mandarin.

It might also be worthwhile noting that:

- This device was manufactured by Bosch, a company headquartered in Germany

- It was being used today at an event held by a different German company in Shanghai

Jenny tells me that both the quality of the device and the quality of the interpretation were absolutely fine.

The translation glitch — "Devin" instead of "German" — is odd, because everything else on the panel is translated into reasonably acceptable English. I suppose that this lapse was triggered by someone who knew German better than English or was — at the moment they translated language #7 — thinking in a mixture of German and Shanghainese instead of English and Mandarin.

Jeff B. said,

November 9, 2015 @ 11:20 pm

I've seen this before. 德文 is a common Chinese-character rendering of the English name Devin.

Tor Lillqvist said,

November 10, 2015 @ 12:12 am

And why the odd phrase with "The Netherlands"? The wording is odd, and Bosch is, as you say, a German company. Confusion between "Deutsch" and "Dutch"?

Brendan said,

November 10, 2015 @ 1:04 am

It seems sort of odd to be using 文 wén for spoken language in this context — for "Original Voice," e.g., I'd expect 原聲 yuánshēng rather than 源文 yuánwén, which sounds to me as if it should be referring to the source of a translated text. (Or 原文 would, at least — I'm not so sure about 源文, as written here.) In any event, I agree with Jeff B. — 德文 is a transliteration for "Devin," and may just be here as the result of someone plugging each of these language names into a machine translation app and then using the output without checking it.

Michael Wolf said,

November 10, 2015 @ 10:15 am

Well, ok. That makes sense. What I came up with was Greek via some convoluted reasoning involving incomprehensibility (as in http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1024) , "heavenly" made "divine" and then misspelled. I didn't have a good answer as to why a relatively minor language would appear next to those heavy hitters, though.

Victor Mair said,

November 10, 2015 @ 3:11 pm

From Richard VanNess Simmons:

It would be Dēq-ven in my Romanization.

Calvin said,

November 10, 2015 @ 4:03 pm

@Tor Lillqvist

The voice conferencing product is made by Bosch Security Systems B.V., a subsidiary of Robert Bosch GmBH. It was acquired from Philips in 2002 but the company is still based in Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

See Company Profile.

Jeff B. said,

November 10, 2015 @ 11:38 pm

There really is no need for convoluted theories about Shanghai dialects, or where the device was manufactured, etc. As I mentioned earlier, 德文 is the transciption for the name "Devin."

Simply type "德文" into Baidu's translator, for example. You can find this at http://fanyi.baidu.com

It translates to "Devin" as a 人名.

Open and shut.

Jeff B. said,

November 10, 2015 @ 11:51 pm

The real mystery is why Baidu fails to translate it as "German" as well, as that is the most obvious translation.

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2015 @ 7:58 am

@Jeff B.

Not "Open and shut".

Baidu Fanyi gives five example sentences for 德文; three of them refer to German.

Baidu Fanyi gives "Han Wen" for 韓文, but the panel on the Bosch simultaneous interpretation device gives "Korean". If the person who did the translation for the panel on the device were following Baidu Fanyi, you'd expect "Han Wen" instead of "Korean" for 韓文.

We don't even know for sure which direction the translation was going, from Chinese to English or from English to Chinese.

There's also the problem of the anomaly that the spoken languages are referred to as wén 文 ("writing; written language; text"), as astutely pointed about by Brendan (the strangeness of it also struck me the first time I read the contents of the panel). Reliance on Baidu cannot account for that.

Brendan also alluded to another weird aspect of the panel — referring to "Original Voice" as yuánwén 源文 ("original / source text"). It's doubly weird because — although you can understand what they're trying to say by 源文 — the more common orthographic form would have been yuánwén 原文, but that still means "original text", not "original language", which is what they really should have said in English. The proper Chinese for that would be yuányǔ 原語.

Using Google Translate, Baidu Fanyi, Bing Translator, and iciba, I checked out all of the translations on the panel going in both directions — from English to Chinese and from Chinese to English. Reliance on none of these online translation services can account for all of the unusual features of the wording on the panel. I submit that whoever did the translation on the panel knew both English and Chinese well enough not to have to rely on any online translation service, but was fundamentally just winging it based on what they knew of the two languages in their head. In the end, though, their command of both languages taken together was insufficient to avoid the pitfalls that I and others have pointed out.

Brendan said,

November 11, 2015 @ 8:22 am

For a quick test just now, I tried plugging a list of various "wen"s into Baidu Fanyi — because Baidu and Google are using statistical methods rather than rule-based methods for their translations, the same word can sometimes be translated differently in different contexts. This happened with the list below, in which 經文 was originally translated correctly as "scripture" but then became "text" once I added a few things after it. Something similar happened with 愛斯基摩文 ("Eskimo"), which I just threw in there as a curveball: it was initially rendered correctly as "Eskimo," and then got reduced to "text" once the list got a bit longer. Strangest of all, the order of the items in the list changed: initially the order was preserved, but for some reason Baidu Fanyi reshuffled things after a little while. The rendering of 德文 as "Devin" stayed consistent throughout, despite the abundance of contextual clues pointing to "German" rather than a personal name.

Source: "法文、英文、德文、韓文、日文、俄文、經文、愛斯基摩文、原文、源文、正文、譯文。 "

Baidu translation: "Devin, Han Wen, English, French, Japanese, Russian, text, text, text, the source text, text, translation."

Google translation: "French, English, German, Korean, Japanese, German, scripture, Eskimo text, the original source text, text, translations."

(Google does much better, as you can see, but curiously it collapses 原文 and 源文 into a single item, translated [correctly, if wordily] as "the original source text.")

Baidu Fanyi seems to be consistent in its mistranslations of 德文 and 韓文, regardless of context. There may be a desktop translation app that would generate a better match for the weirdness on the sticker — I tend to blame Kingsoft's 金山快译 for all mistranslations everywhere by default, since it's the app responsible for most if not all of the unfortunate renderings of 干 out there — but for the time being, I'm guessing that this is a case of machine translation combined with sloppy human proofreading that caught some of the mistakes but not all of them. (This would also account for "Original Voice," which better matches 原声, as a translation for 原文.) Not as satisfying as blaming it all on the robots, but it seems like a better fit.

Jeff B. said,

November 11, 2015 @ 9:21 am

“If the person who did the translation for the panel on the device were following Baidu Fanyi, you’d expect “Han Wen” instead of “Korean” for 韓文”

You’re absolutely right, if we assume the translators were using Baidu Fanyi, which we cannot. This is why I said “for example” when I suggested Baidu. In fact, I made my original suggestion of 德文 being a transcription of the name “Devin” before I even thought to reference Baidu, in light of my personal experience with the very conundrum we are discussing right now.

We can only speculate. Perhaps the translator did in fact use Baidu but already knew the proper translation of 韓文 but not 德文, not unreasonable given the relative cultural and geographic proximity to China. Perhaps the translator was using a different translation platform. Perhaps the translator recognized "han wen" as being the same letters as the pinyin and had the insight to double check elsewhere. Perhaps there were multiple translators.

“Baidu Fanyi gives five example sentences for 德文; three of them refer to German.”

I noticed that too. But it’s unlikely that somebody using Baidu to translate a single word is going to care much about the example sentences. We’re not translating Shakespeare, after all.

Given the evidence, I would be absolutely floored if it was anything other than a transcription-translation mix-up.

But it's fun to imagine.

Victor Mair said,

November 11, 2015 @ 11:43 am

@Jeff B.

"I would be absolutely floored if it was anything other than a transcription-translation mix-up."

I think we all would be.

What else were you imagining, that it was an open and shut case of everything coming from Baidu?

Jeff B. said,

November 11, 2015 @ 11:29 pm

@Victor Mair

I should have been more specific in my last post. I meant that I would be floored if our mystery language "Devin" is anything other than 德文 transcribed into the English name Devin. That is the only thing I have ever suggested in this whole discussion. I never hinted that the translators even used Baidu at all. I think I emphasized this fairly clearly in my previous post. I simply offered Baidu as one example of a translation service (it's the only one I bothered to check).

You suggested a mixup involving Shanghainese, German, Mandarin and English. It's an interesting theory. All I ever intended was to offer another theory that explains the mistranslation much more simply. I then provided some supporting evidence, specifically a major Chinese translation service intended for Chinese users that unequivocally translates 德文 into English as Devin, which is provided as a 人名. How this particular translation service translates 法文 or 俄文 or 韓文 is completely beside the point because we cannot assume the translator(s) even used it. I only intended to introduce a precedent for this particular mistranslation.

My mistake was saying "open and shut," because of course we don't know for sure what caused the translation glitch, and I apologize if it came across as dismissive of anyone else's suggestion.

flow said,

November 12, 2015 @ 8:31 am

As for 原/源/元, those are characters I find always hard to use correctly, in a similar way I find it hard to differentiate eg 作 vs 做 and 意 vs 義 correctly. Maybe I'm not the only one.

There's a tendency in the tradition of the Chinese script to 'elaborate' or 'enlarge' characters. For example, the character for 'net', read wang, started out as 网, a perfectly simple and memorable pictograph, albeit without hint to its reading—which is why 亡 (also read wang) was added to form 罔. That rebus still lacked a semantic hint, so 糸 (thread, silk, textile) was added to yield 網. In theory, that should be perfect, because it's a character with a clear pictorial representation, a perfect hint for the sound, and a helpful indicator to its meaning, so what can go wrong? Answer: (1) Now you have three characters 网罔網 where there used to be one. Unsurprisingly, people tend to make a difference where they find one, language being shy of perfect homonyms. (2) With big complexity comes big squinting. Whereas 网 is cheerfully simple, 網 looks like your typical run-of-the-mill character, like thousands of its kind. It actually has a near-identical twin in 綱 (confusingly simplified as 纲), so you have to look very closely.

In a like way, 原/源/元 came about as variant ways to denote similar concepts (although possibly from different directions; zdic.net glosses: 原: 最初的,开始的. 本来; 源: 水流所从出的地方. 事物的根由; 元: 头、首、始、大. 基本). Please don't try to tell me these concepts should be written differently because they're 'not same'—people happily use 原 to denote 'plateau', ignoring the existence of 塬 for that meaning, and 元 for 'round' instead of 圓圆. I think 元文 would be just as understandable as 漁网 (or 魚网, indeed). Fanning through the pages of the Xinhua dictionary makes me feel that *that* part of the plan to simplify the Chinese script—reduce the number of characters in use—never really caught on. And now we have the backslash of digital text processing; as my old professor of Japanese put it: "characters did look like kind of on their way out among young Japanese, but now that everyone owns a computer, people spew out masses of the most arcane characters, just because they can". Maybe the person in charge felt that 原文 is 'too simple', 'can't be that simple', and 'more complex is more correct', so 源文 it is.

As for the 文 in 德文, 英文, 中文, I have long given up on insisting it must denote written text; it's a fact of everyday usage that these terms are used indiscriminately for spoken and written language, just as much as 單字 (lit. 'single character') is often used in the meaning of 'word', 'vocable', 'lexeme'.

And, of course, "Design and Quality The Netherlands", totally.

Calvin said,

November 12, 2015 @ 4:03 pm

@flow, regarding the subtle differences between 原/源/元, my observations are:

原: original noun. E.g. 原料 (raw material), 原本 (as noun) original copy, (as adverb) originally

源: origin. E.g. 来源 (source), 淵源 (beginning, origin). Darwin's "On the Origin of Species" is commonly translated as 《物種起源》

元: first; beginning. E.g. 元年 (first year of a Chinese era like 民國元年), 元首 (head of state), 狀元 (first rank in imperial exam)

flow said,

November 14, 2015 @ 7:04 am

@Calvin—you're completely right and I do not deny that there are discernible differences in the application of 原/源/元 (and 淵, another character with the reading of yuan and a gloss that includes "根源、本源", albeit read in the first, not the second tone).

Based on personal experience with the orthographies of some languages, I'd venture to say that there are in Chinese more than a few characters that native speakers need a fair amount of education, drill, and dedication for in order to keep them faithfully apart in practice, simply because their differentials as concerns pronunciation and meaning are so minuscule. A database of orthographic errors in Chinese writing would be helpful to asses that effect (and for sure someone has already done that).

I can offer a native speaker's point of view of a similar problem in German. There are two 'little words' you have to use all the time, 'das' (one of the articles, 'the', also used as a relative pronoun) and 'dass' (conjunction, 'that'). They sound exactly the same in everybody's speech, and are a frequent source of spelling mistakes in German. Heck, people find the distinction so difficult this single question has its own website (http://www.das-dass.de/)! My hypothesis is that if native speakers had two neatly distinguished compartments in their language faculties for the two lexical items, they'd have less daily trouble in getting it right in the written. People who argue in favor of distinguishing 'das'/'dass' like to point out that they're different parts of speech and should, therefore, be distinguished in the written, but those who support a single written form for both point out that other 'little words' in German fulfill different roles, too, without anyone feeling the need to introduce variant spellings for those roles. No great ambiguity is present in speech, at any rate; and when writing that old Wupperthalian joke in the local dialect—A: "darf dat dat?", B:"Dat darf dat!", A:"Dat dat dat darf!" no-one feels the need to write 'dat' here and 'datt' there. In conclusion, the 'das'/'dass' split is an artificial, merely orthographic addition that maybe helps to make written texts clearer, but certainly does make German orthography a bit more difficult.

Mutatis mutandis, the above outlines my suspicion when it comes to the role of 'character tuples' (like 原/源/元, 作/做, 意/義) in MSM: The respective characters in the tuples may show subtle distinctions in their dictionary definitions and some can probably be traced back to different readings and/or semantics; however, they're easily mixed up precisely because their distinction is at least in part a purely orthographic add-on rather than a deep fact of language (that, on the other hand, the same character is used to write both 'original' and 'plateau' is another quirk of orthography, but of course those meanings are so different that they're not so easily confounded).

JS said,

November 14, 2015 @ 11:30 pm

@flow

Then you ought to love this… not sure whether to feel guilty or proud of my atrocious performance.

flow said,

November 15, 2015 @ 1:31 pm

@JS looks promising but I just see that 开始 button and nothing happens when I click on it; tried on 2 machines, 4 browsers

flow said,

November 15, 2015 @ 1:54 pm

One more thing that came to my mind regarding 源文/原文: as Tom Mullaney (https://history.stanford.edu/people/tom-mullaney, http://news.stanford.edu/news/2012/november/chinese-typewriter-historian-112812.html) has pointed out, predictive text input is a technique that Chinese and Japanese typesetters and typists invented even before the advent of the computer; today, it is an important ingredient for any reasonable character input method, especially when coupled with an adaptive algorithm that learns what words you use so the IME can improve its suggestions.

That has its drawbacks however; already from my writing about 源文 and 原文 here, my IME has picked up the wrong / less accepted spelling, meaning that because I used that spelling in the past I will more likely "repeat that mistake" in the future. Sure I can switch that learning algo off, I probably can even edit my personal vocabulary as stored by the IME, but how many users ever configure their software?

So another possible explanation for the choice of characters in 源文 is that the person writing the text had previously (maybe inadvertently) trained their software to prefer 源 over 原 in some contexts.

Would sure be great if IMEs could hint at the sources of sugestions, e.g. by coloring the background or somesuch.