An inquiry concerning the principles of morals

« previous post | next post »

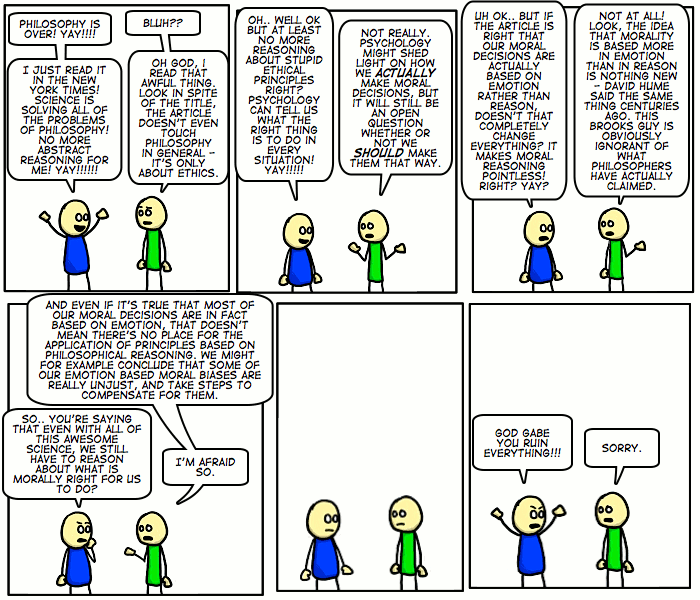

In my role as self-appointed David Brooks watcher, I wearily contemplated his latest masterpiece of misunderstanding, and wondered whether the linguistic angles justified a post. Imagine my relief when I discovered this lovely dissection in cartoon form at chaospet (click on the image for a larger version):

The title of this post, by the way, is taken from a work that David Hume wrote on the same general themes as David Brooks' piece — minus the bloviating about "the end of philosophy" and other sorts of "epochal change" allegedly now being caused by the ideas that Hume discussed at length in 1751.

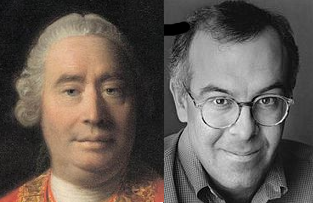

I'm not a cartoonist, but I'll set up a virtual dialogue between these two authors with their Wikipedia headshots:

David Brooks (1961-) , whom Wikipedia a calls "a political and cultural commentator", is now the designated conservative columnist at the New York Times. Here is the start of his column "The end of philosophy", NYT, 4/6/2009:

Socrates talked. The assumption behind his approach to philosophy, and the approaches of millions of people since, is that moral thinking is mostly a matter of reason and deliberation […]

Today, many psychologists, cognitive scientists and even philosophers embrace a different view of morality. In this view, moral thinking is more like aesthetics. […]

Think of what happens when you put a new food into your mouth. You don’t have to decide if it’s disgusting. You just know. You don’t have to decide if a landscape is beautiful. You just know.

Moral judgments are like that. They are rapid intuitive decisions and involve the emotion-processing parts of the brain.

David Hume (1711-1776), whom the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy calls "the most important philosopher ever to write in English", published An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals in 1751. From its opening section ("Of the General Principles of Morals"):

There has been a controversy started of late, much better worth examination, concerning the general foundation of MORALS; whether they be derived from REASON, or from SENTIMENT; whether we attain the knowledge of them by a chain of argument and induction, or by an immediate feeling and finer internal sense; whether, like all sound judgment of truth and falsehood, they should be the same to every rational intelligent being; or whether, like the perception of beauty and deformity, they be founded entirely on the particular fabric and constitution of the human species.

The ancient philosophers, though they often affirm, that virtue is nothing but conformity to reason, yet, in general, seem to consider morals as deriving their existence from taste and sentiment.

Read the whole thing.

[Brooks' conclusion:

The rise and now dominance of this emotional approach to morality is an epochal change. It challenges all sorts of traditions. It challenges the bookish way philosophy is conceived by most people. It challenges the Talmudic tradition, with its hyper-rational scrutiny of texts. It challenges the new atheists, who see themselves involved in a war of reason against faith and who have an unwarranted faith in the power of pure reason and in the purity of their own reasoning.

The opening sentence of Hume's Enquiry:

Disputes with men, pertinaciously obstinate in their principles, are, of all others, the most irksome; except, perhaps, those with persons entirely disingenuous, who really do not believe the opinions they defend, but engage in the controversy from affectation, from a spirit of opposition, or from a desire of showing wit and ingenuity superior to the rest of mankind.

In the Valhalla of philosophers, Bertrand Russell pounds David Hume on the back and whoops "Bullseye! And from 210 years before he was born!", as they hoist a pint with their friends Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, and Charles Darwin. ]

ACH said,

April 8, 2009 @ 1:17 am

My own sense, from my own intuitions and introspection, is that my actions are based principally on emotion rather than reason, but that doesn't mean reason plays no role. I may reason about the likely consequences of some course of action, and the outcome of this reasoning affects my feelings, which in turn affects my actions. If I believe the consequences of doing something would be very bad, I feel it's not something I want to do. If I believe the consequences of not getting something done would be very bad, this provides considerable motivation to get it done.

Kellen said,

April 8, 2009 @ 2:36 am

while i haven't read the article in full, which i'm not likely to do after discounting it based on the snippets, i did major in philosophy and am now starting a masters program in the same, and have read said work by hume. plus i rather like comics. so this has been a welcome post.

for those interested, Radio Lab out of WNYC new york did a show a while back on morality that covers much of the same ideas but with more sound effects than wordpress typically permits.

Jan Schreuder said,

April 8, 2009 @ 2:38 am

I just want to thank Mark for his work as David Brooks watcher. It affords me the luxury of not having to read him. Keep up the good work Mark and lots of strength and courage.

The Enlightened Despot » Blog Archive » Hume vs. Brooks said,

April 8, 2009 @ 3:20 am

[…] Mark Liberman has a beautiful side by side of passages from David Brooks (today) and David Hume (three centuries ago, and better reasoned). The upshot: the 'novel' problems of science and morality Brooks raises are not novel at all. […]

comwave said,

April 8, 2009 @ 3:38 am

I guess the confusion David Brooks shows is related to Prof. Zwicky's term of "private meangings." Maybe David Brooks has lots of private meanings for the words he reads, hears and thinks.

Logically, simplications as well as exaggerations always have a certain distance from facts. I feel uneasy when hearing these deviations called opinions or ingenious ideas instead of arbitrary interpretation.

But, at the same time, I wonder who would be free from the distortions, small or big. (Probably this kind of sentimental judgment would allow the simple, exaggerated, or arbitrary way of thinking.)

misterfricative said,

April 8, 2009 @ 4:15 am

Actually, I think David Brooks is right. If you can get past his cavalier wording, factual errors, false arguments, and circular reasoning, then his main point stands: unlike history, philosophy was always a non-starter and it really has come to an end. About time too.

Back in Socrates' day it was an honest mistake to think that Reason and Enquiry would discover universal philosophical principles. By Hume's time, philosophers were already having to stick their fingers in their ears and go la la la rather than face the unavoidable facts: not only would this never happen, it was fast becoming an irrelevant goal anyway. ('The end of all moral speculations is to teach us our duty;' Hume; Enq. Conc. Princ. Morals. How quaint!) After Whitehead and Russell, the jig was well and truly up, and it only remained for Gödel to dance on philosophy's grave and DIY existentialism to emerge as the only game in town.

Philosophy is — and has always been — nothing more than a hugely elaborate, failed attempt at post hoc justification of whatever we would like to believe. The useful parts (natural science, linguistics, geography, anthropology, psychology, logic…) were spun off long ago, and if present-day philosophers had any integrity at all, they'd come out from behind their shabby faculty curtains, abandon their deservedly shrinking university departments, and go out into the world to get what my mum would call 'a proper job'.

Wednesday prawns | And Still I Persist said,

April 8, 2009 @ 5:02 am

[…] Mark Liberman over at Language Log takes David Brooks to task over his misreading of alleged scientific findings. Or, better put, Liberman finds a third-party […]

Jonathan Hope said,

April 8, 2009 @ 5:14 am

I'm surprised no one has picked up on this piece of fallacious non-reasoning:

"Think of what happens when you put a new food into your mouth. You don’t have to decide if it’s disgusting. You just know. You don’t have to decide if a landscape is beautiful. You just know."

The history of landscape aesthetics (and garden design) shows quite clearly that what counts as 'beautiful' is both initially decided upon, and subsequently learned. The same landscapes have not provoked the same aesthetic responses at all times.

Similarly with food – the first time I put beer in my mouth I was not very keen, but the social pressures and values surrounding beer in my culture ensured I persisted enough to learn to like it.

David said,

April 8, 2009 @ 5:14 am

Misterfricative wrote: "unlike history, philosophy was always a non-starter and it really has come to an end. About time too." etc etc, which is a statement about philosophy (along the lines of "Philosophy is not a meaningful/useful practice to engage in") and hence a statement in the area of inquiry known as metaphilosophy (which investigates questions concerning philosophy, such as "is philosophy a meaningful/useful practice to engage in?") which is a subdiscipline within philosophy and hence, in saying that philosophy is pointless, Misterfricative is himself doing philosophy, albeit bad philosophy since his argument is less stringent and more question-begging than what would be accepted in a regular department of analytical philosophy.

Furthermore, Brooks also supports a philosophical position within metaethics (and an incredibly controversial one, at that) namely something which one might call "rational intuitionism", namely that we "just know" what is right or wrong. We're only just beginning to inquire scientifically into the psychological mechanisms of moral judgement, and one should be very wary about taking the frontline of research today as settled truth. While it does seem as if we, when asked to make moral judgements on the spot, mostly follow our gut-feelings and do not deliberate very extensively, it is another matter whether we, during a long process of reflection, can revise our judgements and arrive at new beliefs (or sentiments) which we then apply when faced with such situations again. Even the most anti-rationalist moral psychologists, such as Jonathan Haidt, have also granted that professional philosophers are sometimes able to set aside their gut instincts and force themselves to accept the results of their reasoned deliberation even if it conflicts with intuitions.

I do not believe that moral philosophy is out to search for the eternal moral truth (or if it is, it's on the wrong track). This is no reason to stop doing it. When we ask ourselves "what shall we do today?" we try to arrive at something we can live with, something which fits our expectations, desires and values, rather than seeking the one true objective answer to whether we should go to work, stay at home or slit our wrists. Similarly with morality: we ask how we ought to act against others because we as choosing beings cannot help but ask, and we try to answer that question in a way we can live with, which doesn't just take our own self-interest into account but also our innate concern for others.

(And note that I am a philosophy student who's sympathetic to the underlying charge that "there is no truth out there for moral philosophy to discover", but I still believe that moral philosophy is worthwhile. Many philosophers would disagree with me and claim that there IS such a truth out there, and are able to advance some very good arguments for it. If anyone of those stumbles onto this thread, Misterfricative will find himself under even more attack.)

Sam C said,

April 8, 2009 @ 5:41 am

"Philosophy is — and has always been — nothing more than a hugely elaborate, failed attempt at post hoc justification of whatever we would like to believe. The useful parts (natural science, linguistics, geography, anthropology, psychology, logic…) were spun off long ago, and if present-day philosophers had any integrity at all, they'd come out from behind their shabby faculty curtains, abandon their deservedly shrinking university departments, and go out into the world to get what my mum would call 'a proper job'."

And your evidence for any of this is… what, exactly? You don't seem to have any idea what contemporary moral (and other) philosophers do. Your quote from Hume reveals that you haven't understood him either. Russell and Whitehead wrote on the foundations of mathematics, not moral philosophy (and Russell, in other contexts, was confident that philosophers could help us to live better lives). Godel has nothing whatever to do with moral philosophy, or with the sentimentalist theory of ethics in particular, or with the possibility of philosophy in general. So, no, Brooks is not right. He's writing from his usual self-confident ignorance. And so are you.

misterfricative said,

April 8, 2009 @ 7:52 am

Sam C, you're absolutely right: I don't have any idea what contemporary moral (and other) philosophers do. But then, who does? And while this obviously shows my self-confident ignorance, I think it also shows how vanishingly irrelevant philosophy has finally become.

David, I see what you did there with the metaphilosophy thing, but I believe you're mistaken: I wasn't doing bad philosophy, I was doing bad history.

Sam C said,

April 8, 2009 @ 7:56 am

"But then, who does? And while this obviously shows my self-confident ignorance, I think it also shows how vanishingly irrelevant philosophy has finally become."

No, it shows that you don't know what you're talking about. You are not representative of anyone else. Maybe you'd like to act like a grown-up now, and admit that you were talking out of your arse?

acilius said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:09 am

It's surprising Brooks could write as if Hume had never lived. He was an undergrad at the U of Chicago in the early 1980s, when the place still had a strong "Great Books" emphasis and when Hume's prestige was particularly high. I'd think Brooks would have had to take a very unusual academic path to get through there without reading at least some selections from Hume's Enquiry.

Cruss said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:11 am

Mister Fricative in 1945:

MF: Hey, you know what? I haven't heard much about physics lately. Come to think of it, I don't have any idea what contemporary scientists do. I haven't read anything about science for a very long time! I guess that just goes to show how vanishingly irrelevant science has finally become.

The Atomic Bomb: KABLOOM!!!!!!!!

MF: Oops.

misterfricative said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:12 am

Sam, I thought I had just admitted that? But I will happily admit it again: yes, I am talking out of my arse. And I'm sorry to have caused you so much distress.

[(myl) OK, guys, shake hands and go back to the bar while we clean up all the broken glass. ]

Marinus said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:24 am

Though people point to Hume, rightly, as already covering the ground Brooks so injudiciously breezes over, the idea which Brooks is so excited about, that moral judgement is a lot like perception, is far older than even that. Aristotle had such a view, 2500 years ago. He'd agree wholeheartedly with the point that you just see something as right or wrong (more fully, as kind, just, friendly, cowardly, gluttonous, etc). He then gave a very rigorous philosophic analysis of what such judgements consist in, on what grounds they could be appropriate or not, why such judgements matter, how to cultivate a more discerning faculty of judgement, and so on. And Aristotle, you'd better believe, certainly didn't believe that these analyses of his made an end to that 'philosophy' misadventure Socrates and Plato flirted with!

misterfricative said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:57 am

Cruss, nice one! I tremble to think that metaphysicians might even now be secretly deploying the world's first philosophy bomb…

Mark, my bad. I apologize. Send me the bill for the broken glass.

Kenny V said,

April 8, 2009 @ 9:41 am

Historically philosophy has isolated itself in an ivory tower, but I feel like these days it's just starting to develop a nice working relationship with science, understanding the relationship to be one where science investigates stuff that philosophy then uses to inform its own understanding and subsequently help brainstorm where science should look next. I'm thinking particularly of cognitive science. I'm thinking of Dan Dennett.

Kelly said,

April 8, 2009 @ 10:09 am

PZ Myers, of Pharygula has also covered this topic. He covers it from the point of view of scientific research. PZ points out that Brooks was responding to scientific research.

rootlesscosmo said,

April 8, 2009 @ 10:25 am

This being a blog about language and all (an interesting construction now I come top think of it), I'd just like to point out that the opening sentence Mark's post quoted from Hume–the last quote in the post–strikes me as a piece of outstandingly good English expository prose, clear, well-formed and -phrased, and with a tone of detachment–the kind some modern English speakers associate with "taking things philosophically"–that David Brooks would do well to study.

Mike Scanlon said,

April 8, 2009 @ 10:27 am

I would like to suggest a look at Antonio DeMassio's "Descartes Error" Demassio is a leading neuroscientist and takes the position based on study of brain function observed in fMRI studies that the dichotomy is a false one, that reason is not possible without emotion, and emotion is a very hard wired matter selected by evolution. His explanation does not degrade either but unifies them in a way that makes a great deal of sense.

bianca steele said,

April 8, 2009 @ 10:32 am

Mark, you shouldn't let David Brooks get under your skin. Brooks has his audience and you have yours. Pretending what he writes is worthy of comment by scientists amounts to pretending he is on the same plane as scientists, thoughtwise, and leads to incoherent if not comic results. It's not like what you say is going to make any kind of dent in his head, or anything; he knows what he knows and that's that, I'm pretty sure.

[(myl 4/8/2009 14:17) My only problem with David Brooks? So many targets, so little time. Well, maybe there's also the suspicion that poking fun at fools, even highly-placed ones, is bad karma. Seriously, I don't aim to make any kind of dent in any part of Mr. Brooks' anatomy — this post was mostly a chance to introduce a few people to something by David Hume that they might not have read. And the cartoon was funny. ]

I'm going to tack up this synopsis by Will Wilkinson above my desk so I can remind myself on any given Tuesday or Friday what's really going on.

More on Brooks and Moral Philosophy said,

April 8, 2009 @ 10:53 am

[…] Liberman has an excellent post including a cartoon and telling passages from Hume's […]

Arnold Zwicky said,

April 8, 2009 @ 11:47 am

Mike Scanlon: "I would like to suggest a look at Antonio DeMassio's "Descartes Error"…"

Make that Damasio.

Sam C said,

April 8, 2009 @ 11:57 am

Oops, that came across far more aggressively than I intended it. Apologies.

snart said,

April 8, 2009 @ 12:22 pm

As a sociologist long frustrated, amused, appalled by Brook's amateurish musings about and applications of research from my field, to the philosophers I say, Welcome!

John Emerson said,

April 8, 2009 @ 12:40 pm

This is only somewhat on topic, but few who write about Haidt's five innate roots of morality ever seem to note that society, civilization, and progress require that we repress or limit many of them. Examples include the desire for revenge; honor killing; contempt for slaves, serfs, and peons; servility toward superiors; taboos of various kinds; blind loyalty and xenophobia; and resentment of the rich and powerful.

Our society honors benefit/harm and fairness over the others, and that's OK. Haidt's typology does help us understand radically different systems better, and maybe they're OK too, in a relativist sense. But there's no society that perfectly develops all five roots equally.

Ray Girvan said,

April 8, 2009 @ 12:46 pm

Kenny V: these days it's just starting to develop a nice working relationship with science, understanding the relationship to be one where science investigates stuff that philosophy then uses to inform its own understanding

And vice versa – where philosophy can be a tool for analysing scientific discovery (for instance, biomedical situations where technical feasibility impinges on traditional taboos).

John Emerson said,

April 8, 2009 @ 12:47 pm

Mark, you shouldn't let David Brooks get under your skin. Brooks has his audience and you have yours. Pretending what he writes is worthy of comment by scientists amounts to pretending he is on the same plane as scientists, thoughtwise, and leads to incoherent if not comic results.

I think that all smart people should vigorously protest all stupidities in the mass media. The stupider the media, are the stupider the voters get, and the stupider the voters get, the worse the government gets. People like Liberman, Krugman, and PZ Myers are doing the Lord's work (with an asterisk for Myers at least).

John Emerson said,

April 8, 2009 @ 12:50 pm

As far as philosophy finally getting in touch with science goes, they've been doing that for 400 years or more. Descartes, Leibniz, and even Kant weren't exactly out of touch with science, and since about 1930 science-oriented philosophy has become increasingly dominant in the English speaking world. But analytic philosophy's way of being scientific was a very peculiar one.

Mark F. said,

April 8, 2009 @ 1:02 pm

The funniest thing is how oblivious Brooks is to the undermining nature of the scientific work he's writing about. Conservatives are especially committed to the idea that right and wrong exist independently of human opinions. If we believe that the kind of result he is discussing tells us anything about right and wrong, that is, if we align ourselves with the blue character in the cartoon, then are basically accepting the idea that right and wrong are just artifacts of human evolution.

peter mcburney said,

April 8, 2009 @ 1:19 pm

Misterfricative (at 4:15 am) said: "Philosophy is — and has always been — nothing more than a hugely elaborate, failed attempt at post hoc justification of whatever we would like to believe. The useful parts (natural science, linguistics, geography, anthropology, psychology, logic…) were spun off long ago, . ."

Well, actually, "long ago" is not correct. Speech act theory from the philosophy of language, which in English dates from the work of philosopher John Austin in the mid-1950s and philosopher John Searle in the 1960s (there was earlier work in German), has turned out to be very useful for the design of artificial languages for computer-to-computer communication. Similarly, the philosophy of argumentation, which dates from Aristotle but had a renaissance from the 1960s, mainly due to philosopher Charles Hamblin, turns out to be useful in designing machines able to reason, both alone and in collaboration, and has spurred the creation of the new field of computational argumentation. The philosophy of (human) desires and intentions, especially the work of philosopher Michael Bratman, has helped create, in just the last two decades, an entirely new branch of computer science, autonomous agent and autonomic systems, concerned with software programs able to control their own execution. All of the areas of computer science mentioned in this paragraph now include deployed applications, and organizations which have sponsored this research include NASA, Boeing, Hewlett-Packard and IBM.

Given the fact, therefore, that useful parts of philosophy are still arising and being spun off, there would seem to be a good (indeed, utilitarian!) case for keeping the discipline of philosophy alive and paying people to do it.

Brooks on the End of Philosophy « The Catholic Liberal said,

April 8, 2009 @ 1:40 pm

[…] Apparently .I'm not the only one to rise to the defense of philosophy. Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)Moral […]

SJ said,

April 8, 2009 @ 1:42 pm

Interesting post. The one omission which I found striking was "experience." At least as far as I can make out from my own emotions to situations and object, generally, they tend to be something shaped by experience in the past. So, for instance, if I like certain foods (as someone else pointed in the comments, a large error in the NYT op-ed), it is due to having eaten them a great deal in the past. And did I always like that food? No. Hence, the notion of acquired taste.

And when I look at a landscape, it is merely informed by a first reaction? No. Generallly, there's a selective comparative/contrast (pattern-recognition) going on in the background that evokes emotions such as nostalgia.

Much of the evolutionary psychology current now seeks to say that human beings are born with hard-wired evolutionary traits. However, in pushing the envelope on this theory, many such psychologists betray a tendency towards saying that experience (the nurture part of psychology debates) does not play a role. While human beings could well be hard-wired with certain traits (for instance, I found it fascinating that my nephew and niece were radically different personalities from the very beginning of their respective lives), experience plays a role in deciding how we will act, be it emotionally or through some internal logic.

Matt Heath said,

April 8, 2009 @ 2:23 pm

"Make that Damasio."

If we are being strict about this make it "Damásio" and also "António".

bianca steele said,

April 8, 2009 @ 2:55 pm

myl: My only problem with David Brooks?

Brooks's "science" columns inevitably fall into one of the following categories:

1) People vote only for candidates they like, so parties should put up candidates "most people want to have a beer with."

2) People don't (and shouldn't) think, because most of the thought we act on is done already by the culture (or whatever).

3) Belief in the attributional fallacy is optional: middle-class people succeed in life and are happy, because middle-class people have traditional culture values that they transmit to their children, and poor people can only succeed and be happy if they have the opportunity to be educated in part by those middle-class traditional cultures.

Peter Muhlberger said,

April 8, 2009 @ 3:22 pm

I'm a social scientist who has done a bit of work in moral psychology and more work in related areas. Brooks gets the psychology wrong. A lot of current neuroscience research on issues such as the trolley problem (see description in wikipedia) does not show that people's response is purely emotional, but rather that there is activation in parts of the brain that neuroscientists suspect are linked to both emotional and cognitive processing. Activation of emotional areas are more prominent for certain ethical dilemmas than for others (e.g., Whether to push a fat man in front of a train so several people down the track might live. Who comes up w/ inane stuff like this?). How accurate neuroscientists' understandings of what is going on when parts of the brain are activated can be questioned. For example, while the emotional regions see more activity with the fat man dilemma, is this actually informing the decision or is it simply a consequence of an earlier cognitive evaluation or a response to the situation that has no effect on the decision?

Brooks also leaves out the fact that virtually no psychologist has ever proposed that people do a lot of deliberative thinking with respect to ethical questions. An earlier generation of moral psychologists (Piaget, Kohlberg, Rest, Turiel, etc.) thought morality did have to do with 'reasoning' by which they meant hidden structures of thought to which people did not have direct access. For example, when people hear their language, they immediately understand it, without much, if any, self-conscious cognitive processing. The cognition involved is automated and outside the awareness of the person. Similarly, these psychologists contended that moral judgments are typically automated, which means they appear to be not reasoned through, even while there are cognitive processes behind them. Those cognitive processes can, however, be brought under conscious consideration by a person's effort to try to understand how they arrived at a certain judgment. To bring automated moral cognition under consideration, a person must create a linguistic model of their automated presuppositions. Once such a model exists, it can be subject to reasoning, quite possibly improving upon it. In philosophy, there is a great deal of effort to come to grip with moral 'intuitions' in this way.

These earlier moral psychologists developed a mountain of compelling research that shows that the reasoning behind moral judgments become more sophisticated and, arguably, more adequate as children grow into adults. A substantial body of their results also shows that sophistication of moral judgments does predict moral behavior.

This approach to moral psychology died off, I suspect due to a number of factors that are irrelevant to the validity of the theories involved: 1) key people died, 2) the best measures of moral reasoning proved to be quite difficult and graduate students were generally not keen on spending years learning the techniques required, 3) much of the research anyone could think of doing had already been done, and 4) the hot new area of research became neuroscience, which has such crude tools of measurement that it is impossible to adequately capture the kinds of things in which the older generation of moral psychologists were interested.

What I find disconcerting is how readily the new neuroscience approach to research on moral reasoning can find itself hijacked for ideological purposes. Many types of conservatives like the neuroscience approach because it can yield (or be readily misinterpreted to yield) value and social prescriptions that they like, such as: a) morality is an absolute etched into the brain, b) morality is black and white, c) people are basically non-rational and so social order is achievable only with authoritarian rule, d) people's nature cannot be changed so we should not be thinking of new social forms but work instead with traditions that have proved themselves useful in maintaining social order for millennia etc.

interesting article « partisan food said,

April 8, 2009 @ 4:17 pm

[…] A discussion of the column by the resident Brooks-checker at Language Log. Possibly related posts: […]

J.W. Brewer said,

April 8, 2009 @ 6:23 pm

Another great Hume quote that belongs here is "Reason is, and only ought to be, the slave of the passions," which might be paraphrased "up yours, Marcus Aurelius, and the horse you rode in on, too." I agree with misterfricative (I think) that the entire post-Hume project of attempting to ground a non-nihilistic morality on "philosophical" (in the sense of non-religious, non-supernatural) foundations is an embarassing nonsense-on-stilts failure and a lot of time could have been saved if everyone had just read Hume and given up before they started. Although I'm not sure if that was Brooks' point. If philosophers are no good at morality, are they any better at linguistics?

Perezoso said,

April 8, 2009 @ 7:01 pm

Hume's made reference to "passions" rather than emotions, did he not, when taking down rational ethics: Reason must be a slave of the passions, or something. So, yes, Liberman is correct to point out that Brooks points out nothing new; at the same time, it's always amusing to hear the latest naturalist like Brooks blithely claim Reason's nothing but an instrument for passion, emotion, desire, that Justice is an illusion, unscientific, etc. Say an Imam felt the desire to issue a Fatwa calling for the death of the pro-war infidel Brooks: that's neither good or bad, reasonable or unreasonable, Davey? At least Davey would probably want to say some desires and emotions are better than others, right.

Arnold Zwicky said,

April 8, 2009 @ 7:37 pm

Matt Heath: " [AMZ] "Make that Damasio."

If we are being strict about this make it "Damásio" and also "António"."

This is silly. We are talking about how the man's name is spelled in English (and how he spells it on his books). I only posted a correction in case someone wanted to try to find his books on-line (in which case "DeMassio" would have been problematic). I intended to be helpful, not nit-picky. I see now that this was a mistake.

comwave said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:33 pm

Thanks to Prof. Zwicky's correction, I could find this page;

http://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/papers/damasio.htm

Have we lost even a minimum understanding for others' intentions?

Interesting was the fact that Google has sort of "intelligence" when I got the search results as follows;

Antonio DeMassio's "Descartes Error"…" : 2 results

Antonio DaMassio's "Descartes Error"…": 3 results

Antonio Damasio's "Descartes Error"…": 29,800 results

And one of the first 2 result took me to the above linked page.

Anyway thanks for Prof. Zwicky and his scrutiny.

comwave said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:36 pm

Typo: "of the first 2 result –> of the first 2 results" in the second line from bottom.

links for 2009-04-08 « Overton’s Arrow said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:38 pm

[…] Language Log » An inquiry concerning the principles of morals (tags: morality philosophy David.Brooks newspaper opinion cartoon) Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)links for 2009-01-06CarnivalsOn big-government libertariansLIBERTY: The proper role of Government! […]

comwave said,

April 8, 2009 @ 8:44 pm

One thing I remember now is that I first took the "morals" in the title of this post as "modals." And I was looking the cited comic mainly in terms of the usages of modal verbs. I was probably influenced by the previous discussions in LL.

So far I thought language may dictate mind and thought. But from this experience, now I come to think sometimes mind and memory may dictate language.

Fuck Grapefruit said,

April 9, 2009 @ 4:32 am

Cat. Pigeons. A Prepositional Relationship….

Crikey. My recent comment on Language Log didn't quite play out as I'd anticipated. A bit of colorful bloviating to make an observation that seemed not only long overdue and obvious, but also not even particularly controversial… and oh …

Chris Horner said,

April 9, 2009 @ 5:39 am

Hume, unlike Brooks, has a lot of wise things to say about morality, and the way it is grounded in 'sentiment' (feeling). One shouldn't forget, though, that an alternative tradition (back to Aristotle) takes the cognitive aspect seriously: ie, the view in short that our emotions are, by definition, more than blind feeling – that emotion is 'directed' to objects and that this is permeated by out judgments about what we conceive to be good, conducive to flourishing etc.

Thus, reason need not be passion's slave.

Funny how conservatives want it to be, isn't it?

Stephen Jones said,

April 9, 2009 @ 7:10 am

At least the argument over the spelling of Antonio Damasio has taught me the rules for accentuation in Spanish and Portuguese are wildly different.

Wikipedia spells both names with the accent. It is an interesting question as to whether English should copy the accents or not. The purpose of the acute accent is twofold; to distinguish the vowel from a shorter variant of the same vowel, and to show where the stress is when it would not be clear from the spelling. As English would put the stress naturally in both cases in the same place as the Portuguese, and as the different phonemes (or allophones) would be represented by the same vowel in English, you could make a good point for missing out the accents as being too busy.

Matt Heath said,

April 9, 2009 @ 7:16 am

Arnold Zwicky "This is silly": Actually, you are right, sorry. I've developed a knee-jerk thing for telling people to put that accents on Portuguese names, because you often see tildes left off and that really messes with the pronunciation. But there was no call for it here.

Agin, sorry.

Paul Wilkins said,

April 9, 2009 @ 5:50 pm

He sure wouldn't enjoy reading Kant. But, if Brooks is an economic conservative, he *must* subscribe to the rational self as actor and self-interest as primary motivation for action. It's central to Adam Smith's teachings.

And there are consequences to his line reasoning. For instance, if you act based solely on your passions and rationalize them post, then what is the point of learning a moral framework such as that taught in a church?

He is either setting himself up for something big (like coming out of the closet and revealing a crack addiction) or just becoming completely unglued. Reminds me of a particular TV news network…

What Socrates Really Said: a Reply to David Brooks : The Uncredible Hallq said,

April 9, 2009 @ 6:59 pm

[…] Wilkinson, Massimo Pigliucci, and Mark Liberman have all been beating up on David Brooks' recent column on philosophy and moral psychology. […]

Jonathan said,

April 9, 2009 @ 7:09 pm

"What shapes moral emotions in the first place? The answer has long been evolution, but in recent years there’s an increasing appreciation that evolution isn’t just about competition. It’s also about cooperation within groups."

In recent years there's also an increasing appreciation that these ideas aren't quite so novel…

"It must not be forgotten that although a high standard of morality gives but a slight or no advantage to each individual man and his children over the other men of the same tribe, yet that an increase in the number of well-endowed men and an advancement in the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage to one tribe over another. A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection." (Darwin, The Descent of Man)

Anon said,

May 8, 2009 @ 2:05 pm

You realize, I hope, that as the "designated conservative columnist at the New York Times," Brooks' only reason for existing is to provide a mouthpiece for left-wing strawman constructs of right-wing beliefs so that progressives can feel open minded and smug about their reading habits. Nothing he says or writes should be taken seriously.