Sinographic memory in Vietnamese writing

« previous post | next post »

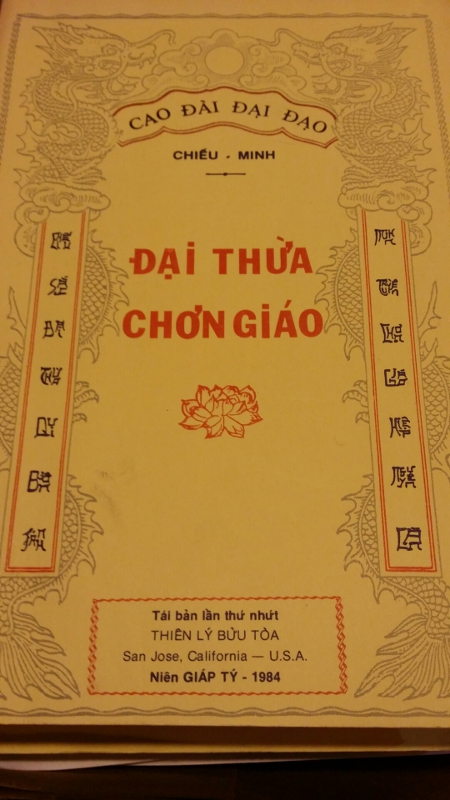

Jason Cox sent in the following photograph of the cover of a Vietnamese religious text and asked what was going on with the "characters" along the left and right sides.

This immediately reminded me of Square Word Calligraphy (writing English words in the shape of a square, like Chinese characters), originally created by Xu Bing in 1994, a new version of which was developed by David B. Kelley in 2012.

Before tackling the "characters" in vertical columns on the left and right, let's see what sort of text this is.

At the top it reads: "Cao Dai Great Way" (Cao Dai is the popular, monotheistic religion in the Mekong delta). The large red letters in the middle say "True Teachings of the Great Vehicle (Mahayana)". For more on the Cao Dai, see Millenarianism and Peasant Politics in Vietnam (1983) by Hue Tam Tai.

Our text is a Vietnamese prayer book. Here is a rendering in Chinese characters and English of the horizontal lines on the cover:

高台大道

照 . 明

—

大乘真教

first republishing

天理宝 (name of publisher)

San Jose, California—USA

Year 甲子 — 1984

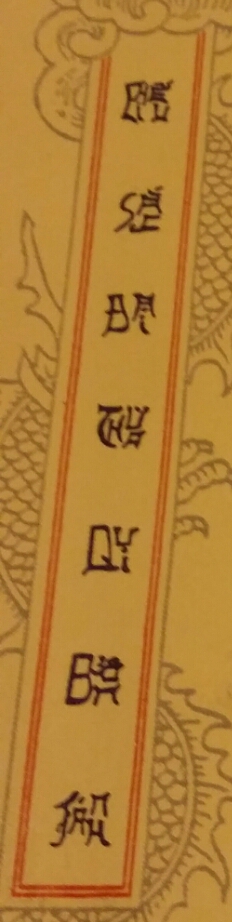

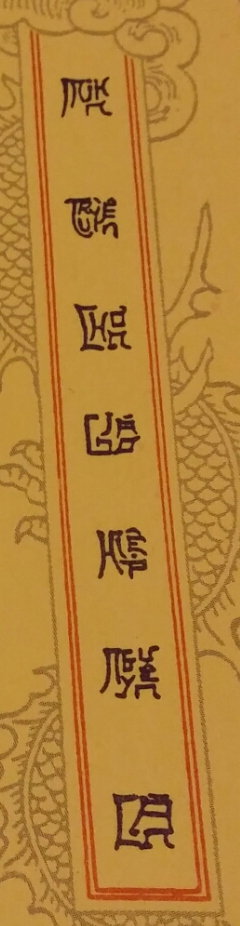

Now on to the vertical columns, where the alphabetical Vietnamese is made to look like Chinese; it is a very common ploy to link new texts to ancient (read "Chinese") and thus sacred texts. The blocks on the periphery are formed by squeezing the Vietnamese letters that make up normal written syllables into a square matrix so that they appear to be Chinese characters. If you look carefully, you can even see the tone marks. Most are too stylized to be read with ease, and few people try to read them anyway. They are primarily decorative.

Steve O'Harrow explains:

This is an attempt to write modern Romanized Vietnamese [quốc ngữ] in something that approximates the flavor of what the Vietnamese usually call "chữ nho" or "chữ hán," i.e., Sino-Vietnamese. Given that it is a Cao Đài religious tract and that Cao Đài is highly eclectic, it's not too surprising that they would find it æsthetically pleasing to refer in some way to a long-gone classical past which 99% of their adherents are in no way capable of deciphering (not unlike most modern Vietnamese). I have often seen this kind of faux-Chinese writing in places like restaurant signs and on clothing shops catering to the romantic tourist trade in Hanoi and TPHCM [VHM: Ho Chi Minh City] – It's kind of like "Ye Olde Englishe" on pub signs in London.

Here are a couple of examples of the way the "squaring" of the words works.

C H I Ế U = first word on the left

|

C

|

H

|

Ế

|

|

I

|

U

|

S Ắ C = second word on the left

|

S

|

Ắ

|

|

C

|

Tô Lan deciphered the Vietnamese words (not so easy!) and provided the Chinese characters.

The two columns need to be read from right to left.

MINH TRUYỀN CHƠN GIÁO HIỆP NGUYÊN CĂN

CHIẾU SẮC ĐẠI THỪA QUY BỔN TÁNH

明传真教协原根

照敇大乘归本性

Míng chuán zhēnjiào xié yuángēn

Zhào cè Dàshèng guī běnxìng

English translation by Denis Mair:

Clearly transmit the true teaching to assist the inborn root;

Illuminatingly implement the great vehicle to return to original nature.

English translation by Jiang Wu:

Brighten and transmit the true teaching, contributing to the original root;

Illuminate and promote the Great Vehicle, returning to the authentic nature.

English translation by Tingyu Liu:

Preaching the sutra in a wise way to follow its original root;

Brightening the true color of Mahayana to return to its nature.

The first two translations are based on a sinographic restoration of the second syllable of the second line, SẮC, as cè 敇, whereas the third translation is premised on sinographically restoring that syllable as sè 色 ("color").

All three translators provided detailed justifications for their understanding of the lines, but they are too technical to insert here. I will, however, mention two philological notes that are essential and accessible. First, it is difficult to distinguish cè 敇 ("whip [as a horse]") from chì 敕 ("imperial edict / order"), since they both look alike (the difference being that the rectangular "box" at the middle on the left side of the second character is closed on all four sides, but it is open at the bottom in the first character) and sound somewhat similar.

The first character, 敇, is rare (few modern readers recognize it) = 策 ("whip" –> "urge forward" –> "promote"). Cf. Fó cè dàshèng 佛敇大乘 ("The Buddha promotes Mahayana").

Secondly, until about 25 years ago when I started campaigning against the mispronunciation, most people mistakenly read 大乘 as dàchéng ("greatly mount") instead of as dàshèng 大乘 ("Great Vehicle").

For another example of Square Word Alphabetical Vietnamese writing, see Wm. C. Hannas, Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, p. 93, this one for an ancestral altar.

[Thanks to Nguyen Ngoc Hung, Lan Nguyen To, Cuong Le, Steve O'Harrow, Hue Tam Tai, John Balaban, Jiang Wu, Tingyu Liu, and Denis Mair]

Victor Mair said,

April 16, 2014 @ 6:16 pm

From Michele Thompson:

Let me add a bit about the rest of the book, as Stephen says it's a Cao Dai religious text, specifically a book of sermons and homilies, it's a reprint of a book that was originally published in Gia Dinh in southern Vietnam, the earliest copy Yale has is listed as 1950 and that one is the second edition so the first edition was probably published just a few years earlier. It is specific to a branch of Cao Dai founded by Ngo Van Chieu who essentially founded the branch known as Chieu Minh when he refused his election as Cao Dai Pope and left the "See" at Tay Ninh. It's not surprising that this was reprinted in San Jose as there is a large Cao Dai Temple of the Chieu Minh branch in San Jose.

Victor Mair said,

April 17, 2014 @ 6:59 am

From a correspondent:

It is believed that this is a "modern" version of the book:

http://tamgiaodongnguyen.com/Kinh/DTCG.htm

In the couplet, 6 words are in capital letters:

CHIẾU MINH

ÐẠI-THỪA CHƠN-GIÁO

>From the order of the words, it seems that the couplet should be read

from left to right, which is, of course, an "improper" way to deal

with a couplet.

Victor Mair said,

April 17, 2014 @ 7:14 am

From the correspondent who sent in the previous comment:

明传真教协原根

照敇大乘归本性

1. "佛敕" ("Buddha's edict" or "the Buddha orders someone to …") does make sense as "佛敕" is not a rare phrase in Chinese Buddhism.

2. according to the tones of 根 (平聲)& 性(仄聲), the proper sequence should be:

照敇大乘归本性

明传真教协原根

languagehat said,

April 17, 2014 @ 8:35 am

The oldest edition in WorldCat is from 1937.

Ben Zimmer said,

April 17, 2014 @ 10:22 am

[From Matt Anderson.]

This phenomenon is fascinating. I’ve also seen this kind of writing in a temple in Vietnam:

Sorry the writing is cut off at the bottom—I think I have a better photo somewhere, but I can’t find it at the moment. This is a small structure in the Chùa Trấn Quốc Buddhist temple in Hanoi. (A side note: The sinographic form of Chùa Trấn Quốc is 鎭國寺, though the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation of those characters would be Trấn Quốc Tự, not Chùa Trấn Quốc. Chùa means ‘pagoda’, but it is a different word from 塔; I believe its Chữ Nôm form is 廚 over 寺.) I think it’s interesting that the sinographic alphabetic writing here coexists with the purely sinographic 寒林所.

Most of the writing in this temple is written in (standard, classical Sinitic) Sinographs, with a few more recent signs written in standard, horizontally-written Quốc ngữ.

There are also some strange structures that I think are stupas:

I don’t really have a good idea what’s going on with this writing. Is it perhaps an indic script written in a more sinographic form? Or just something imaginary? I took these pictures in 2008 and had completely forgotten about them until reading this post.

Victor Mair said,

April 17, 2014 @ 10:37 am

Note how the square shaped graphs in Matt's first photograph have been rounded.

J. M. Unger said,

April 17, 2014 @ 11:13 am

By the way, notice the similarity of this Vietnamese style of arranging roman letters into sinogram-like frames and Xu Bing's famous art work using English words (as on the cover of Mary Erbaugh's _Difficult Characters_).

Y said,

April 17, 2014 @ 1:05 pm

Is Vietnamese đài historically related to Mandarin dà in any way (i.e. through borrowing)?

A-gu said,

April 17, 2014 @ 2:47 pm

@Y, it most certainly is:

http://www.chunom.org/pages/%E5%A4%A7/

And that pronunciation is close to one of the literary readings in S. Min/ Holo Taiwanese (大道公 Tāi-tō-kong), Hakka (放大 biong55 tai55), and Cantonese (大人 daai6 jan4).

Victor Mair said,

April 17, 2014 @ 2:47 pm

From a Vietnamese scholar:

I am so used to sinographic writing that I don't stop to think about it. Sinographic writing can be either round or oval or square or rectangle.

There is a wikipedia entry for the Tran Quoc pagoda, originally built in the sixth century during the very short time (503-548) when Ly Bi or Ly Nam De (Ly, Southern Emperor) was on the throne. Ly Bi was a descendent of a clan that had fled the Wang Mang usurpation into northern Vietnam (Jiaozhi).

The "stupas" in Matt's photographs are a very recent abomination by a Vietnamese businessman with more money than sense or taste. Besides the stupas, he also filled part of the lake so that cars could drive into the pagoda's grounds. Fortunately, he was stopped before he could inflict further damage. I brought David Faure and his team of CUHK-based scholars and Jim Robson as well as some Vietnam scholars to tour the pagoda in 2012.

Matt Anderson said,

April 17, 2014 @ 5:10 pm

Thanks to the quoted Vietnamese scholar for the information about the "stupas". That does help explain things. They certainly did look out of place surrounding the pagoda.

Matt said,

April 17, 2014 @ 8:52 pm

The figures on the stupas look a lot like bīja, "seed syllables". For example in the top photo, the top one looks a bit like "āḥ" and the bottom one looks like "tāṃ".

Vāṇiprīta said,

April 18, 2014 @ 6:44 am

佛敇 is a translation of Skt. buddha-śāsana, the standard term for the Buddha's teaching. The general meaning of the verbal root śās is "to chastise, punish, correct, restrain" which fits 敇 "whip" quite well, but in Buddhist texts derivatives of this root (śāsana, śāstra, śāstṛ, etc.) are semantically closer to "teaching/teacher."

The modern Hindi loanword does mean "control, punishment." The recent Kollywood film translates śāsana as "The Rule":

http://www.filmykhabar.com/pictures/shasan/5353/

Victor Mair said,

April 18, 2014 @ 7:14 am

I think that the letters on the sides of the sides of the recently erected stupas are a form of Siddham, with somewhat exaggerated or emphasized rectangularity (as Matt suspected), for obvious reasons:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siddha%E1%B9%83_alphabet

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/siddham.htm

https://www.google.com/search?q=siddham&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=PRVRU6btKbXfsAS41oKQCA&ved=0CDoQsAQ&biw=1370&bih=676&dpr=0.9

Milan said,

April 18, 2014 @ 10:57 am

To me this (both the Sinographic writing and the letters and the stupa, given that Victor Mair is right, and they are based on Siddham) seems to belong to the same category as the myriad of Latin fonts that mimic the appearance of other scripts. Of course the Vietnamese writing is more creative and shows far superior craftsmanship than those novelty gags.

Examples in Alphabetic Order:

Faux Arabic: http://www.fontspace.com/category/faux-Arabic

Faux Chinese Cursive: http://www.fontspace.com/juan-casco/ming-imperial

Faux Cyrillic: http://www.dafont.com/theme.php?cat=205

Faux Devanagari: http://www.fontspace.com/category/faux-sanskrit

Faux Greek: http://www.dafont.com/theme.php?cat=204

Faux Hebrew: http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/pixymbols/faux-hebrew/

Faux Runes: http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/pixymbols/faux-runic/

Even "Fake Hieroglyphs" do exist: http://www.dafont.com/fakehieroglyphs.font

However, none of this digital fonts seems to have an analogue precursor and I'm lead to believe that this kind of imitative writing is a rather recent innovation in the West, despite multiple writing systems coexisting in Europe since the antiquity.

hanmeng said,

April 18, 2014 @ 11:51 am

This has nothing to do with Vietnam, but speaking of Square Word Calligraphy:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-6mTipaEZouE/U1FSbS7km0I/AAAAAAAAA8o/HqhcchRyl3M/s1600/shirt.jpg

Suburbanbanshee said,

April 18, 2014 @ 4:50 pm

Fake fonts were used in advertising, movie titles, etc. for many years before they ever became digital. I'd say it's been around for at least a hundred years, probably a good deal longer in the case of fake Chinese and fake Japanese fonts.

I have seen some medieval European artwork from Spain which was apparently ripping off Arabic writing by adding random scribbles. Whether this was due to illiteracy in Arabic or mistaking the motifs for abstract design, I don't know, but I think there was a whole exhibition or book of European art that imitated Arabic and Mozarabic stuff. I think it was a lady who put the exhibit together, and I'm pretty sure I saw it on the Internet and not in person.

Levantine said,

April 19, 2014 @ 3:56 am

There's a kind of Arabic script known as Sini that is used by Chinese Muslims and imitates the look of Chinese characters, which is a surprising twist on the other cases discussed above. Here's a good example by Haji Noor Deen Mi Guanjiang, who's the most famous practitioner of this style of calligraphy (the bottom section is written in a regular Arabic script): https://www.flickr.com/photos/swamibu/338386895/.

I know (from what I've been told) that in some of his works, Haji Noor Deen arranges the Arabic such that the end result can actually be read as real Chinese characters of appropriate meaning. I don't know if that's going on at all in the image in the link, where the words are turned on their side and barely legible as Arabic.

Victor Mair said,

April 19, 2014 @ 6:45 am

@Levantine

Thanks for the excellent reference to Arabic written so as to appear like Chinese characters. Your mention of turning them on their side to make them readable as Chinese makes them ambigrams.

http://chinese-ambigrams.blogspot.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambigram

The Wikipedia article prominently cites Douglas R. Hofstadter, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. I am surprised that it doesn't mention David Moser, who translated G, E, B into Chinese and who is a friend of Hofstadter, since David is the most outstanding practitioner of Chinese-English ambigrams.

http://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/tag/ambigrams (N.B.: "Cognitive China" seems no longer to belong to David, but has been taken over by a Japanese website.)

I'll have to let the editors at Wikipedia know about this.

As for turning things on their side to be able to read them, that reminds me of the time Erika Gilson — a Turkish linguist and specialist on various forms of early Turkic languages who is familiar with Arabic script and other relevant types of Middle Eastern and Central Asian writing — came to my office and saw a Manchu text laid out on my table. She cocked her head to the side and said, "I can sort of read this." And she did, without ever having seen, much less studied, Manchu writing before.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchu_language

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sogdian_alphabet