Vocabulary

« previous post | next post »

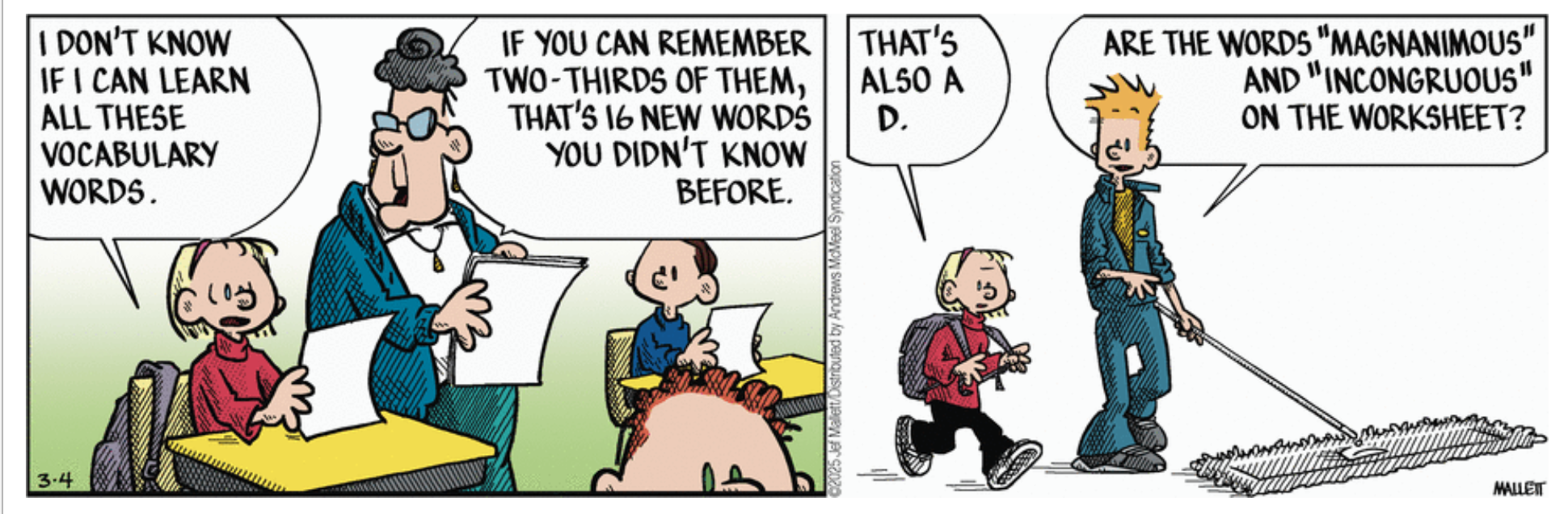

Tuesday's Frazz:

George Miller was eloquently skeptical about the value of traditional vocabulary lessons, compared to everyday experience. From George Miller and Patricia Gildea, "How Children Learn Words", Scientific American 1987:

Our findings and those of other workers suggest that formal efforts to build vocabulary by sending children to the dictionary are less effective than most parents and teachers believe. […]

In the early grades schoolchildren are expected to learn to read and write. At first they read and write familiar words they have already learned by means of conversation. In about the fourth grade they begin to see written words they have not heard in conversation. At this point it is generally assumed that something special must be done to teach children these unfamiliar words. This educational assumption runs into serious problems. Although children can recognize that they have not seen a word before, learning it well enough to use it correctly and to recognize it automatically is a slow process. Indeed, learning a new word entails so much conceptual clarification and phonological drill that there simply is not enough classroom time to teach more than 100 or 200 words a year in this way.

Miller notes that informal learning through speech and reading is where the real action takes place, with about 13 words a day learned over the course of 16 years:

For the purpose of counting, a word can be defined as the kind of lexical unit a person has to learn; all the derivative and compound forms that are merely morphological variations on the conceptual theme would not be counted as separate words. For example, write is a word and its morphological variants (writes, writ, wrote, written, writing, writer and so on) are relatives in the same family. If such a family is counted as a single word and knowing a word is defined as being able to recognize which of four definitions is closest to the meaning, the reading vocabulary of the average high school graduate should consist of about 40,000 words. If all the proper names of people and places and all the idiomatic expressions are also counted as words, that estimate would have to be doubled. This figure says something about the ability of children to learn words. If the average high school graduate is 17 years old, the 80,000 words must have been learned over a period of 16 years. Hence the average child learns at the rate of 5,000 words per year, or about 13 per day. Children with large vocabularies probably pick up new words at twice that rate. Clearly a learning process of great complexity goes on at a rapid rate in every normal child.

If 2/3 of the Mrs. Olsen's test items was 16, then the whole list was 16*3/2 = 24 items long. So by Miller's calculation, Mrs. Olsen's 24-item vocabulary test was about two days worth of natural word learning.

Of course, natural word learning is a more gradual process, with several encounters in context generally involved for each item. Miller notes that an experiment from 1978 showed somewhat-effective learning from a single encounter (Susan Carey and Elsa Bartlett, "Acquiring a single new word", Papers and Reports on Child Language Development 1978). But he describes two stages of the word-learning process:

[A] child's appreciation of the meaning of a word seems to grow in two stages, one rapid and the other much slower. Children are quick to notice new words and to assign them to broad semantic categories. […]

The slow stage entails working out the distinctions among words within a semantic category. […]

This stage ordinarily takes much longer than the first and may never be completely finished; some adults, for example, correctly assign delphinium and calceolaria to the semantic field of flowering-plant names but have not learned what plants the words denote and cannot identify the flowers on sight. At any given time many words will be in this intermediate state in which they are known and categorized but still not distinguished from one another.

Miller's educational conclusion is that "a computer program providing lexical information about new words encountered in the context of a story might be more effective." And modern educational practice has largely learned this lesson, I think, though some Mrs. Olsens are no doubt still Out There.

Cervantes said,

March 6, 2025 @ 8:25 am

Of course, it can happen — rather frequently, I think — that people encounter a word many times, and never grok the correct meaning. An example I've often run into is "erstwhile," which people seem to think means something like admirable or exemplary. I also had a colleague who was very offended when I wrote that physicians sometimes exhort their patients to take their medicines. She thought exhort meant something improper. It doesn't hurt to consult the dictionary when you encounter an unfamiliar word.

Jenny Chu said,

March 6, 2025 @ 10:12 am

I suppose the type of instruction and the age of instruction matter a great deal. I recall fondly a vocabulary book I used in fourth grade (9 years old) that taught us 40 new words per week and now, 40 years later, I am certain I internalized every one of them. It had a wonderful series of daily lessons of increasing difficulty, starting with putting the words into blanks of sentences and ending with writing stories based on the words. But later efforts were much less effective.

Upon reading Zuleika Dobson for the first time, in my late 20s, I did my own vocabulary exercise since there were so many unknown words in there. I learned with much greater difficulty than I had at 9.

jhh said,

March 6, 2025 @ 11:05 am

How might this apply to trying to get *college* students to learn new vocabulary? I ask my students to earmark words they encounter in their assigned readings they don't recognize/understand, and ask them to gloss those words as part of the assignment. I'm sometimes shocked by the words they say, at least, they don't know: "antique," "scholar," "partial"…

Important concept-bearing words are formally introduced in lecture, turn up in readings, and are used in discussion in small groups. Those words seem to stick… but what do I do to improve the chances that my liberal arts students graduate with a richer vocabulary?

I'll grant: they will all continue to build their vocabularies after graduation… and they will eventually learn the words they need. So, should I just give up the effort?

Anthony said,

March 6, 2025 @ 12:14 pm

"Bemused" and "nonplussed" are right up there with "erstwhile." As an aside, I've noticed that books aiming to improve one's foreign language vocabulary concentrate on nouns and verbs almost to the exclusion of adjectives and adverbs. It's as if one mightn't ever need the word for "alleged" or "apparently."

Peter Grubtal said,

March 6, 2025 @ 12:18 pm

This theme is dead set to provoke a fit of my Kulturpessimismus. In one's L1 language you'd have a rich reading history through childhood and adolescence, and vocabulary acquisition came without being aware of consciously working towards it. Do the kids nowadays spend all their time on their mobiles, and don't read?

Of course, with L2 as an adult, you really have to work at it (or I did).

Cervantes said,

March 6, 2025 @ 1:23 pm

Note that the use of nonplussed as essentially the antonym of its original meaning has become common enough that it gets a dictionary entry, labeled as "informal." Some other words (cleave, e.g.) have opposite meanings, but in this case you can't necessarily tell from the context which is intended. If someone says that "Fred was nonplussed by Elon Musk's actions" you have no idea how Fred reacted. There's a lengthy discussion of this at Merriam Webster.

David Marjanović said,

March 6, 2025 @ 1:52 pm

There are certainly, and already were 30 (and no doubt 40 and more) years ago, children who practically don't read books (much of what you do on a mobile is read and write, so this specification is necessary). But, my shock notwithstanding that English vocabulary was ever taught to native speakers like a foreign language, this post is actually grounds for some minimal Kulturoptimismus:

Julian said,

March 6, 2025 @ 4:43 pm

"The slow stage entails working out the distinctions among words within a semantic category. […] This stage ordinarily takes much longer than the first and may never be completely finished…"

Personal favourite: "hysteresis"

General semantic category: "something you may read in an academic paper."

?Feynmann?: "if someone explains something to you, and you say 'I *think* I understand' in that doubtful tone, that means you don't."

Jon said,

March 7, 2025 @ 2:02 am

i had the misunderstanding of erstwhile once. It's an easy mistake to make if someone is introduced as "My erstwhile colleague". You think "They seem to be happy about it, it must be complimentary".

On the other hand, I have never come across nonplussed as unruffled. And the word hysteresis triggers an image of a small cathode ray tube displaying hysteresis in real time, in green.

But the larger point is about what you are counting when you talk about the size of someone's vocabulary. There is a scale going from "That's a real word, I saw it somewhere once, no idea what it means or how it might be used", to full understanding, with many gradations between. I am always puzzled when people talk about size of vocabulary without specifying what level of understanding they are talking about.

Jerry Packard said,

March 7, 2025 @ 7:58 am

Of course we’re talking about reading here, which is one degree at least from the spoken words used in everyday life. Our focus on literacy is highlighted by words like

Colonel

Lasagna

Sword

Phlegm

Island

Knight

Knife

Wednesday

Salmon

Corps

which are enough to drive any child or second-language learner crazy.

If we’re prepping them for high school entrance exams or SAT or GRE, then teaching them how to visually distinguish them from their distractors might be the best strategy. Teaching them literacy skills is something else.

Even such an innocuous word like ‘something’ threw me for a loop in a first-grade reading class one day when asked to read aloud after being absent for a few days!

cM said,

March 7, 2025 @ 3:55 pm

I'm more than a bit befuddled by the use of "vocabulary words" in the comic. As opposed to… non-vocabulary words?

A quick googling confirms this to be a term used in (American?) education. I still don't get what information it conveys that would be more than just: "words".

Philip Taylor said,

March 7, 2025 @ 5:14 pm

I asked virtually the same question, cM, but my comment was almost immediately deleted (one assumes, "moderated"). I still have no idea why.

Barbara Phillips Long said,

March 8, 2025 @ 6:08 am

"Vocabulary words" or "spelling words," in my experience, are forms of lessons about American English words in U.S. education. For instance, when I was in elementary school in the 1950s, we had reading primers such as the Dick and Jane books, but we also had social studies or geography books, and later, history. Those books would have chapters on different subjects followed by a list of words (the "vocabulary words," or, occasionally, the glossary) that the book authors expected the reader would not automatically know, followed by reading comprehension questions, and perhaps other exercises.

The social studies/geography/history classes and their readings reinforced reading instruction, enlarged vocabulary, and provided knowledge in fields other than English and mathematics. In the U.S., reading/"language arts"/English instruction mostly has students read fiction, with limited amounts of poetry, plays, and sometimes nonfiction essays.

Spelling words were often assigned as part of "language arts" instruction in the mechanics of English. Often there would be 10 or 20 words a week that students had to learn, often assigned at the beginning of the week and tested at the end of the week. Different teachers assigned different exercises, which might include copying dictionary entries for the word, writing sentences using the words, copying the word list some arbitrary number of times (three or five, for instance), which was also a covert handwriting practice. Some spelling word lists had themes, such as words with i and e combinations (receive, neighbor, weigh, science, efficient, etc.). Spelling word lists were not necessarily based on lessons that week on other topics such as social studies or science.

So, "vocabulary words," while redundant, is a term of art referring to lessons with words for students to learn to build their working vocabularies (although the vocabulary lessons might or might not include spelling tests), and "spelling words" were words in lessons designed to build and test student skills with spelling American English words and also to increase working vocabulary. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably, since the ultimate goal of the lessons were the same.

Daniel Barkalow said,

March 11, 2025 @ 4:24 pm

In 6th grade, I got fed up with the vocabulary tests (or really, with homework related to them), and convinced my teacher to let me find and learn some words I hadn't already acquired naturally. Of these, the only one I still remember is "gyve" (not "gyre", which everyone knows); I might recognize the meanings of others, or even remember how I learned them if I heard them, but I can only bring "gyve" to mind as being in this category. Trying just now, I thought there was another word I could still identify, but it wasn't "syzygy", which I only learned later by reading the Theodore Sturgeon short story by that name.