Vire-langue ou célébration des homophones?

« previous post | next post »

From jeremy_jeyy:

https://youtube.com/shorts/KrNWFWWsKAs?si=UyaQaem2TTfUdlZp

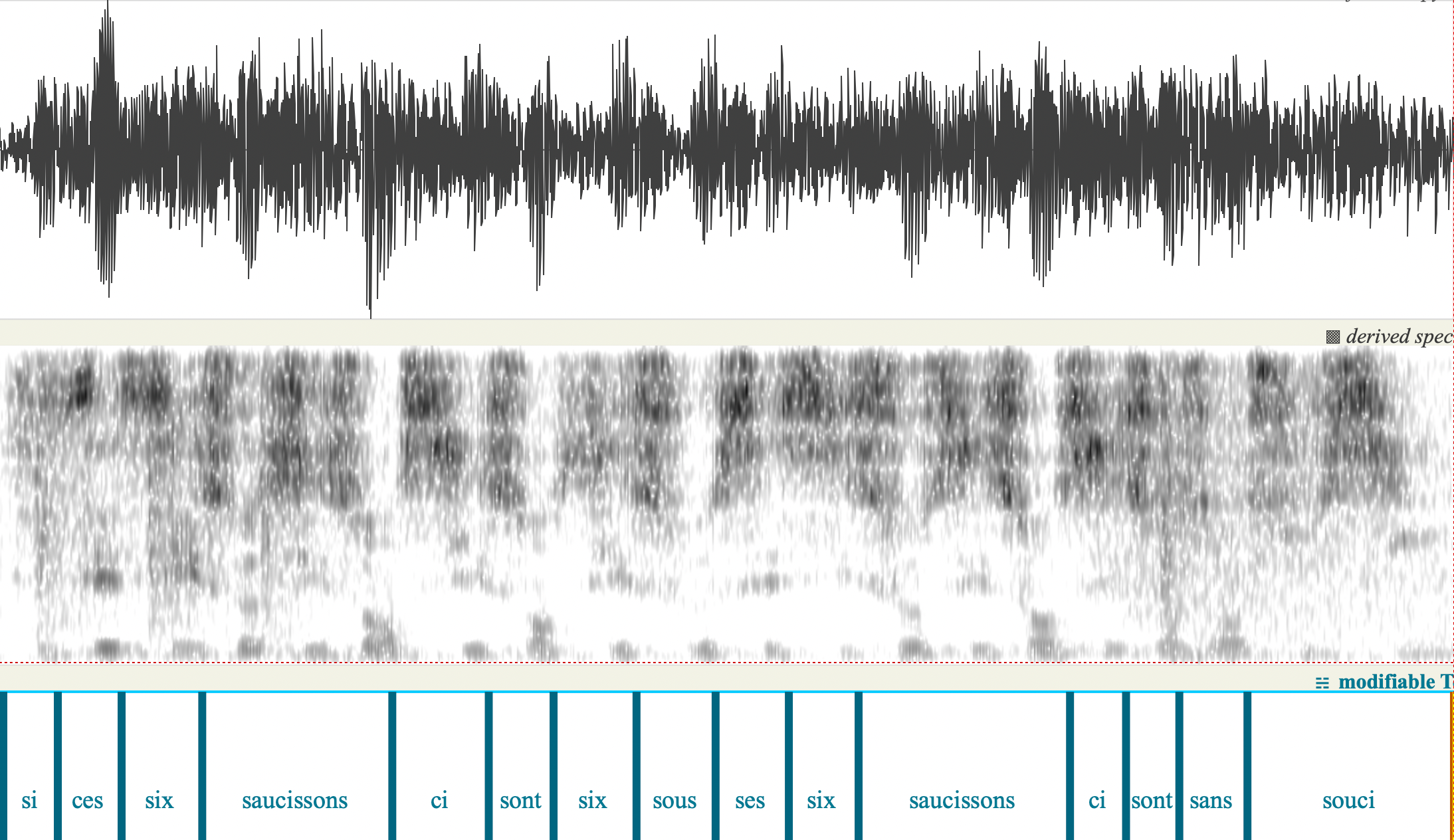

The audio is heavily weighted towards high frequencies, which emphasizes the many /s/ sounds and (along with the rapid unmodulated performance) makes the actual textual content hard to hear:

Si ces six saucissons-ci sont six sous, ces six saucissons-ci sont sans souci.

A link to (the Instagram version of) this clip was sent to me under the heading "French tongue-twister" (in French, vire-langue = "turn-tongue"), but my non-native-speaker impression is that the sentence "Si ces six saucissons-ci sont six sous, ces six saucissons-ci sont sans souci" is not especially hard to say correctly.

Compare English "She sells seashells by the sea shore", which mixes /s/ and /ʃ/ in a way that tends to confuse our brain's execution of the utterance plan. Or the French analogue, "Un chasseur sachant chasser doit savoir chasser sans son chien".

And the rest of jeremy_jeyy's YouTube collection seems also to be mostly about the celebration of (full or partial) homophones, gleefully pronounced, to the stupefaction of his other self — e.g. this example:

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/7fukEm9G708

An adjacent oddity — Google Translate knows that French vire-langue is English "tongue twister":

But in the other direction, it gives us a definition rather than an equivalent word:

Update — there are at least two other performances of related "six saucissons-ci" passages on YouTube, here and here. FWIW, they're explicitly labelled as "tongue twister" and "virelangue".

cameron said,

December 17, 2024 @ 2:27 pm

the version I learned years ago was "six cents Suisses suçant six cents six saucisses dont six en sauce et six cents sans sauce"

but I agree with the point that these aren't tongue twisters in the sense that they're hard to say, they're brain twisters in the sense that it can be hard to parse the spoken language (the written language is no problem, of course).

it's sort of a purely phonetic form of antanaclasis – where the same apparent syllable(s) repeat over and over with minimal further syntax to clarify what is meant

Arthur Baker said,

December 17, 2024 @ 3:02 pm

For the record, the full version of the "she sells seashells" twister:

She sells seashells on the seashore

The shells she sells are seashells, I'm sure

And if she sells seashells on the seashore

Then I'm sure she sells seashore shells

Josh R said,

December 17, 2024 @ 6:43 pm

Japanese tongue-twisters (早口言葉, hayakuchi-kotoba, "quickly spoken words") are typically quite easy to say in isolation. A prototypical example is 生麦生米生卵 nama-mugi nama-gome, nama-tamago (raw wheat, raw rice, raw egg), which doesn't even have many phonemes that sound the same or are produced similarly. The key is, Japanese tongue-twisters are meant to be pronounced three times in rapid succession. And for some reason I'm not entirely sure of, when you try that, difficulty increases exponentially.

Mark Liberman said,

December 17, 2024 @ 7:45 pm

@Josh R: "The key is, Japanese tongue-twisters are meant to be pronounced three times in rapid succession. And for some reason I'm not entirely sure of, when you try that, difficulty increases exponentially."

The hardest English tongue-twister I know is trying to say the two words "toy boat" three times fast.

Viseguy said,

December 17, 2024 @ 11:26 pm

The German In Ulm, um Ulm, und um Ulm herum is a variation on the repetition theme.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 18, 2024 @ 8:46 am

…and who can forget the old "saw": "Si six scies scient six cyprès ci-près, six cents scies scient six cents cyprès ci-près."?

For the non-francophones, that would be: /si si si si si sipray sipray, si son si si si son sipray sipray/

David Marjanović said,

December 18, 2024 @ 10:00 am

Les chaussettes de l'archiduchesse, sont-elles sèches ou archi-sèches?

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

December 18, 2024 @ 10:08 am

Wow, David. I wouldn't be able get through that one at slightly-faster-than-normal-speaking-speed if you'd offered me a lifetime-supply of moules-frites. It breaks down _every_ time, either at "archiduchesse" or "archi-sèches".

How is it that phonemes spoken earlier in a phrase can hobble phonemes later on? What's the psycholinguistics behind it?

Andrew Usher said,

December 19, 2024 @ 9:09 am

Mark Liberman said:

> The hardest English tongue-twister I know is trying to say the two words "toy boat" three times fast.

Yes, that's hard, but it showed me an apparently paradoxical phenomenon – when I stress the phrase 'TOY boat' (as I first did), I can do it trivially. But when I said 'toy BOAT' (as in normal speech) it breaks down as it does for you.

The hardest I've ever come across to say once is "the Leith police dismisseth us" – looks easy, but even once at normal speed, it's almost impossible to avoid switching /s/ and /θ/. Any version of the 'seashells' is easier than that.

David Marjanović said,

December 19, 2024 @ 9:29 am

Something about expectations.

Particularly severe cases may instead belong to neurolinguistics, though.

…oh. I'd never have guessed. Yeah, that does make it more difficult.

Whoa!

This would fit with conflicting expectations as an explanation – -eth is already unexpected, so you enter the phonetic alternation pre-confused.

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2024 @ 7:46 am

I'm not convinced that "-eth is already unexpected", David. I have been aware of (the longer version †) of "The Leith police" for sixty years, and so when I attempt to recite it repeatedly at high speed, the "-eth" is completely expected, yet I still encountered the same /s/ | /θ/ switching problem as those for whom the "-eth" is expected.

† "The Leith police dismisseth us, for we sufficeth them" (used, along with "The quick brown fox", etc., as standard fodder for typing practice).

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2024 @ 7:48 am

s/for whom the "-eth" is expected/for whom the "-eth" is unexpected/w

Andrew Usher said,

December 20, 2024 @ 8:51 am

Yes, surely, the '-eth' being unexpected/unfamiliar is not the whole story there.

I'd like to address this since it came up: the stress of 'toy BOAT'. English compound stress may seem irregular, but the orthography helps! – all compounds written as one word (solid) or hyphenated have initial stress, so only those always separated are subject to variation. Here's the basic facts as I recall.

The general rule is that a noun compound "A B" is stressed on B if it describes a type of B, otherwise not – there are many exceptions in which a fixed phrase acquires initial stress, but those often get written solid or hyphenated, making it clear, and I'd prefer we write 'sea-level' and 'sea-ice' for that reason. A large category of exceptions involves phrases describing humans, and in particular 'man, 'woman', 'person' don't draw the stress (and again, often get written solid or hyphenated).

Proper names (except personal names, always stressed on the surname) are treated like compounds even if they contain an adjective. The most irregular group of these is probably the names of buildings. The most common general terms, 'building', 'house', and 'center' don't draw the stress, but 'hall', 'hotel', and all words for sports facilities other than 'center' do. Very heavy words like 'auditorium' do, but that's less distinctive; I believe 'library' is heavy enough for Americans, but not Brits.

With compounds containing more than two elements, it seems it works to treat them recursively based on logical structure.

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2024 @ 12:19 pm

"all compounds written […] hyphenated have initial stress, " — surely not, Andrew. What about "able-bodied" and "high-spirited", just the first two to come to mind.

Philip Taylor said,

December 20, 2024 @ 12:22 pm

(also) "I believe 'library' is heavy enough for Americans, but not Brit[on]s" — I believe that we Britons are not consistent here : we might well stress the "Bodleian" in "the Bodleian Library" but never stress the "British" in "the British Library".

Andrew Usher said,

December 21, 2024 @ 12:48 am

But able-bodied and high-minded are compound adjectives, nor noun compounds. Those normally follow that pattern, while I was discussing the latter.

Philip Taylor said,

December 21, 2024 @ 3:52 am

Fair enough, Andrew, but your assertion was "all compounds written as one word (solid) or hyphenated have initial stress", not "all noun compounds written as one word (solid) or hyphenated have initial stress" — it was therefore your assertion that I was challenging, not the assertion that it would now seem you had intended.

Andrew Usher said,

December 21, 2024 @ 7:28 am

I agree I may have mis-spoke; I thought I'd written it in a different order than it seems I did. And if any reader took it that way, it would be misleading as I was trying to show that the written form is a generally good guide to the correct stress (almost perfect for place-names).