"…X, let's say Y…"

« previous post | next post »

Justin Weinberg, "Analytic Philosophy's Best Unintentional (?) Self-Parodying", Daily Nous 9/6/2024:

“Someone, let’s say a baby, is born; his parents call him by a certain name.”

That line–recently circulated on social media by Eric Winsberg (South Florida / Cambridge) as “the funniest sentence in the history of philosophy”—is from Saul Kripke‘s Naming and Necessity.

I’m not sure its the funniest sentence in the history of philosophy, but it is pure poetry.

Justin Weinberg added:

*UPDATE: Some are suggesting Kripke’s line was meant to be funny, in which case I suppose we should broaden the request for suggestions to include intentional self-parodies by analytic philosophers.

In the comments, Eric Winsberg responded:

I don’t think he’s joking. You have to remember this is the transcript of a talk. He’s just throwing in very standard though [sic] experiment language. Compare “a number of people, say five, are tied to a railroad track”. You’re just signaling that the number 5 is only important in that it’s more than one. But in Kripke’s case, the whole point of the example is that there’s nothing distinctive about the person at all except the ensuing baptism. So he’s going “someone is born” and he’s brain goes “we need a “say” clause, and ends up making the funniest sentence ever.

Kenny Easwaran added:

I’ve always interpreted this line as a clear self-parody. When he’s trying to stay object-level, he has no trouble coming up with specifics, like naming his pet aardvark Napoleon, or any example involving, say, Nixon. In this case, I think he’s observing the need to include “say X” afterwards, and then filling it in with the one thing that actually adds nothing, rather than “someone, let’s say, the future teacher of Aristotle, is born”.

FWIW, Eric Winsberg's comment about "standard thought experiment language" seems persuasive to me.

In (the transcribed and edited text of) Naming and Necessity, "let's say" is used 18 times as a rhetorical device to introduce a specific but arbitrary assumption for the purposes of the current argument, e.g. on p. 80:

Let's see if Thesis (2) is true. It seems, in some a priori way, that it's got to be true, because if you don't think that the properties you have in mind pick out anyone uniquely — let's say they're all satisfied by two people — then how can you say which one of them you're talking about? There seem to be no grounds for saying you're talking about the one rather than about the other.

He also uses plain "say" for the same rhetorical purpose, e.g. on p. 17:

Nor, when we regard such qualitatively identical states as (A, 6; B, 5) and (A, 5 ; B, 6) as distinct, need we suppose that A and B are qualitatively distinguishable in some other respect, say, color. On the contrary, for the purposes of the probability problem, the numerical face shown is thought of as if it were the only property of each die.

And on p. 87, he uses "let's say" to introduce an assumption arguendo that's vague nearly to the point of emptiness, probably because he didn't care to come up with anything more specific:

What's going on here? Can we rescue the theory? First, one may try and vary these descriptions — not think of the famous achievements of a man but, let's say, of something else, and try and use that as our description. Maybe by enough futzing around someone might eventually get something out of this; however, most of the attempts that one tries are open to counterexamples or other objections.

It might still be true that Kripke was intentionally parodying this device when he said "Someone, let's say a baby, is born" — but Eric Winsberg's hypothesis is consistent with Kripke's overall patterns of usage.

As an aside, it's worth noting that Kripke refers to the baby with the male pronouns "his" and "him", probably because that was a common prescription for generic third-person singular pronouns in 1970 when the lectures were delivered.

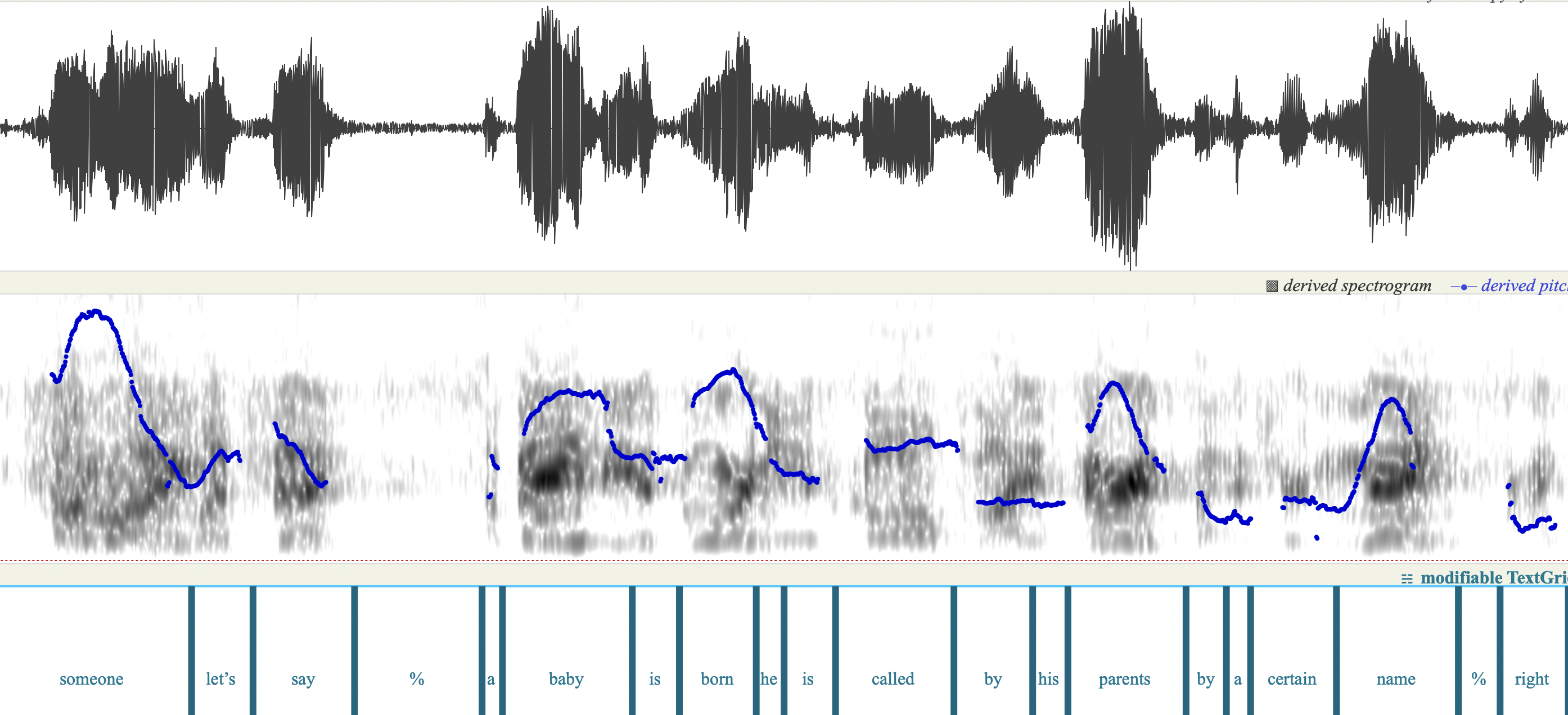

Update — in a comment on Justin Weinberg's post, Brian Rabern provides the audio for the passage in question:

It's relevant that there's a significant pause — about 385 msec — between "say" and "a baby".

It's also maybe relevant that the published paper's wording is different. The audio:

someone, let's say

a baby is born, he is called by his parents by a certain name, right.

they talk about him to their friends, other people meet him

The paper:

The passive "he is called by his parents by a certain name" is turned active, "his parents call him by a certain name". And the tag "right" is omitted.

So the oddly empty arguendo could have been fixed, e.g. by specifying the gender:

Someone, let's say a baby boy, is born;

David Morris said,

September 8, 2024 @ 7:28 am

"Someone, let's say an adult, is born …"

Haamu said,

September 8, 2024 @ 10:32 am

A plausible (to me) alternative would be, “Someone, let’s say a puppy, is born….”

Julian Hook said,

September 8, 2024 @ 11:07 am

"Say" (usually without "let's") has long been common in formal mathematical writing, as when assigning a name to something that has been proven to exist but which has not previously been given a name. For instance: "We have shown that set A has more elements than B. Therefore, there exists some element, say x, such that x belongs to A but not to B."

J.W. Brewer said,

September 8, 2024 @ 3:25 pm

Do we think Kripke, in 1970, was using the "generic he" in a self-consciously prescriptive way, i.e. needing some degree of conscious effort to override a "natural" impulse to use "singular they" instead, or do we think that "generic he" was a "natural" feature of his idiolect, at least in the register appropriate for giving academic talks, such that it was used without any actively prescriptive effort? (Obviously ones "natural" ideolect can contain the residue of previous exposure to prescriptivist norms that took a while to become second nature but eventually did.)

J.W. Brewer said,

September 8, 2024 @ 4:00 pm

The fuller passage as excerpted (hopefully w/o transcription errors) in a piece I googled up:

Someone, let’s say, a baby, is born; his parent call him by a certain name. They talk about him to their friends. Other people meet him. Though various sorts of talk the name is

spread from link to link as if by a chain. A speaker who is on the far end of this chain, who has heard about, say Richard Feynman, in the market place or elsewhere, may be referring

to Richard Feynman even though he can’t remember from whom he first heard of Feynman or from whom he ever heard of Feynman. He knows that Feynman is a famous physicist. A certain passage of communication reaching ultimately to the man himself does reach the speaker. He then is referring to Feynman even though he can’t identify him uniquely.

The context of the ensuing discussion (by the Kripke-interpreter) then seems to presume that the baby in question was the infant Richard Feynman, although Kripke's second use of "say" might cut against that. On the other hand, his abrupt segue from the baby to Feynman is confusing if these are unrelated examples …

J.W. Brewer said,

September 8, 2024 @ 4:35 pm

On further reflection, one interesting fact about babies and pronouns in English is that babies are low enough on the animacy hierarchy that a human baby of unknown sex can naturally and idiomatically be referred to as "it," whereas by contrast "singular they" exists at least in part because we are usually uncomfortable referring to a post-infancy human being as "it." So referring to a baby as "he" can be a way of telling the listener/reader that it's a male baby even if the sex had not been previously specified in the discourse and had not been previously known to the listener/reader. This would be especially pertinent here if it were in fact the case that the baby's parents turned out to be Melville and Lucille Feynman and had given the baby the "certain name" Richard.

Haamu said,

September 8, 2024 @ 8:01 pm

A few hours ago, Brian Rabern, a commenter on the Daily Nous thread, posted a link to the audio of Kripke. (Rabern doesn't offer any authentication, although it might be obvious to anyone familiar enough with Kripke's voice, which I am not.)

What struck me upon listening was the relatively long pause after "say." Another commenter, Adrian Morgan, beat me to the punch:

JPL said,

September 8, 2024 @ 10:31 pm

@J.W. Brewer:

As the transcript indicates, and as listening to the audio recording (see the Daily Nous post) confirms, "let's say" is inserted as an afterthought, after beginning the sentence with "Someone", so that it would be a conversational version essentially equivalent to the "well-ordered" opening, "Let's say someone, a baby, is born …", where "a baby" functions as a correction that clarifies that the speaker means to refer to the event of the christening of an infant, rather than referring to the event as a relatively past event, of an adult's previous christening (e.g., "Feynman's christening"). So, I would say that, to me at least, it's not funny at all, and that the reaction to it as humorous depends on an interpretation based on faulty punctuation (comma usage), perhaps in the published book. (I can't find my dog-eared copy of it right now to check.)

(Kripke is here possibly (I can't check it now for sure, and assuming that JWB's interpretation is correct) concerned with the conditions for the satisfaction of an intended relation of reference, as compared to the critical pragmatic interpretation of satisfied reference for a referring expression, even if it was not intended by the speaker. ("Did you know that that baby that you just called "Richard" grew up to be THEE Richard Feynman?" Some unintended insults also work like this.) But btw, Kripke would not have been able to clarify his own sentence wrt the distinction made in the previous paragraph between the mistaken thought and the corrected thought, two ways of referring to a single event. The two thoughts are distinguished above using referring expressions which are referentially identical (putting aside the fact that Kripke's sentence had a hypothetical intent, not to be judged true or false). He would not have been able to do so because, if he's following Frege's account of reference in the case of propositions and predicates, as referring to truth values and functions respectively, he (Kripke) couldn't refer rather to events in the world (i.e., where Feynman also existed) as being the referents of propositions and predicates in his use of the object language. The "subject- predicate" analysis of sentences has led people astray for a long time, not to mention the notion of "thing objects".)

JPL said,

September 8, 2024 @ 10:34 pm

When I posted the above comment Haamu's comment (8:01) was not visible to me.

Yerushalmi said,

September 9, 2024 @ 5:11 am

I agree with Haamu and Adrian Morgan 100%. It's very clear from the audio that the pause represents Kripke restarting the sentence. It is neither an example of philosophy's excesses nor an example of intentional parody.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 9, 2024 @ 6:54 am

According to the internet, a transcript of Kripke's 1970 lectures was first published in a "proceedings of the conference" type anthology in 1972 before eventually coming out as a standalone book in 1980. If in fact this was the sort of glitch that occurs all the time in speech – where someone starts a sentence, thinks better of where it seems to be going, and then starts anew – it seems at least a little odd that Kripke didn't go back and clean up the MS to eliminate such infelicities, especially before publication of the 1980 edition, by which time I take it it should have been obvious that this was a significant piece of work that was going to have a lasting readership in the relevant specialized niche.* But maybe Kripke himself re-read the transcript after some years and didn't recognize the false-start-and-start-again aspect that the audio makes more obvious. Which would mean he thereby failed to be the ideal interpreter of his own prior utterances.

*FWIW I'm pretty sure we did not read Kripke in the philosophy-of-language class I took in spring '87 in my last semester as an undergraduate, although the syllabus was mostly loaded up with boringly mainstream/canonical analytical-tradition works. I don't know if Kripke had not by then become quite as canonical/ubiquitous as he did later on, or if my particular teacher didn't think as much of him as others did, or what.

/df said,

September 9, 2024 @ 8:41 am

I didn't see any joke, but just assumed the speaker was operating in a universe of discourse where it is not certain, or not relevant, whether "someone" just born is always a baby. This is a philosopher speaking, after all. Morgan's hypothesis of mid-sentence self-correction seemed plausible initially, but the audio clip did not match that interpretation to my ear.

Bybo said,

September 9, 2024 @ 1:41 pm

@JWB

I had a conversation with some Esperanto speakers once. I was referring to a baby (bebo, I think, but might have been infano) as ĝi, and in an afterthought inquired which pronoun those present would have used. All of them were uncomfortable with ĝi and preferred ŝi or li, depending. Most of those present were probably L1 speakers of Slovak, Polish, Russian, or Hungarian. My L1 is German.

J.W. Brewer said,

September 9, 2024 @ 4:50 pm

@Bybo: Thanks, interesting. I should maybe be more explicit that I was not assuming or implicitly claiming that the tacit animacy hierarchy that affects pronoun usage in English would apply in the same way to any other language (Kripke was speaking in English, which was AFAIK his native language), but it's still interesting to get a sense of how it differs from other languages. Of course the Esperantists who were L1 Hungarian-speakers would have had to pick up the whole concept of gendered third-party pronouns as a novelty somewhere along the way.