The further elaboration of a flagrant mistranslation

« previous post | next post »

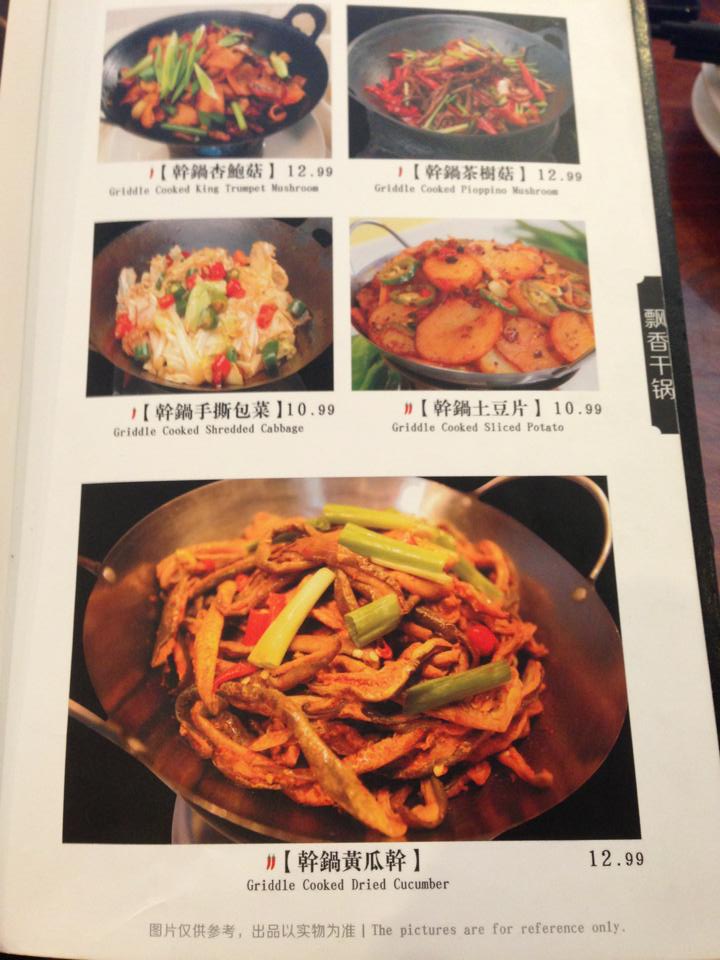

Quincy Lu sent in the following photograph of a menu taken by his wife at a Hunan restaurant in Fremont, California (click to embiggen):

The menu looks innocent enough: five dishes all beginning with gànguō 幹鍋, with the same English translation for all five, viz., "Griddle Cooked". But wait a minute! That's not right! The English is acceptable, but the Chinese characters are wrong; they should be gānguō 乾鍋 ("dry pot / pan / boiler / cauldron" [guō 鍋 is discussed at length in the comments to this post]), not gànguō 幹鍋 ("fuck pot"). The fifth item on this page of the menu actually both begins and ends with the wrong character, since what is meant to be huángguā gān 黃瓜乾 ("dried cucumber") is written as huángguā gàn 黃瓜幹 ("cucumber fuck").

What happened?

We've been through this several times before on Language Log, but the most definitive explanations were given years ago, in "The Etiology and Elaboration of a Flagrant Mistranslation", and in other posts mentioned therein, so it's time for a brief refresher course.

The problem arises from the fact that, in the simplified character system, three characters from the traditional set are collapsed into one, namely, 干. This one little character of three strokes, which originally was pronounced gān, had the following meanings: "to oppose, offend against; a shield; the bank of a river; a stem (including a cyclical / calendrical symbol); attend to, concern; involve; consequences, results; seek; arrange". With simplification, it took on most, but not all, of the meanings and pronunciations of the following two characters as well:

gān 乾 ("dry, dried; clean, exhausted; to possess the name without the true relationship; to hold a position in name only")

qián 乾 — the same character as the preceding one, but with a different pronunciation ("heaven; male, father; sovereign; first of the eight trigrams in the Yi jing / I ching [Book of Changes]") — this pronunciation and set of meanings was not assigned to 干 in the simplified system, but were retained by the original character in its traditional form, which for these specific meanings was taken over as is into the simplified system

gàn 幹 ("the trunk of a tree or the body; business, to attend to business; manage; skillful, capable; do; fuck")

In our previous posts on gān / gàn 干 ("dry; fuck"), we have shown how faulty translation software repeatedly chose "fuck" when "dry" was intended. What makes the current mistake in the Fremont menu so interesting is that this mistranslation has now washed its way back into Chinese, so that the traditional character for gàn, viz., 幹 ("fuck") has appeared in the names of dishes where gān 乾 ("dry, dried") is called for.

Quincy speculates:

The restaurant may be owned by Mainlanders who wish to cater to the local Taiwanese population by using traditional characters in their menu, but whatever manual or automatic process they used to do this converted 干 into 幹. Perhaps they were using the same software that translates 干 into "fuck"!

Quincy also notes that Mandarin speakers from Taiwan are more likely to use gàn 幹 for "fuck," as opposed to Mainlanders who are predisposed to use cāo 操 ("do; exercise; grapple; clutch; grasp; take in hand", etc.), which is a euphemism for the much more graphic (the character consists of "enter" + "flesh") cào 肏 ("fuck"). This is the word that is operative in the famous "grass-mud horse" internet meme, for which see here, here, here, and here.

Daniel Tse said,

August 31, 2013 @ 10:47 pm

Here's a similar case I found at a Sichuan restaurant here in Sydney: http://cl.ly/image/0C150Z3c2p3x

In this example, the menu writers chose to print the menu in traditional characters, but used 祇 (used in HK as the 'formal' traditional form of 只) to render what should have been 隻.

QQ said,

September 1, 2013 @ 4:35 am

Is Victor being overenthusiastic or sarcastic when he translates every instance of 干/幹 as 'fuck'?

Does a native Taiwanese really see 'fuck pot' when they read 幹鍋? I speak Cantonese and the effect of seeing 幹鍋 is similar to what I feel when I read "There going their to pick up they're dog".

Similarly, to me 黃瓜幹 initially has a slightly confusing meaning of 'cucumber stem'. 'Cucumber fuck' does comes up as a 3rd possible interpretation but does not go to the forefront of my consciousness before I realize that 黃瓜乾 is what was meant.

(Though I normally say 青瓜.)

flow said,

September 1, 2013 @ 7:51 am

@QQ i feel the same. 肉干, 肉乾, 肉幹… you get it. but of course, on inspection, 肉幹 isn't correct, and, yes, it's maybe 'meat stalk', or the f* word. it is also quite clear that the chinese—despite they're [sik] rather 'semantic' writing system—do occasionally write in purely phonetic ways, as evidenced by 草泥馬. understanding language, and writing, is always guesswork.

Victor Mair said,

September 1, 2013 @ 8:25 am

@QQ

I certainly do not translate "every instance of every instance of 干/幹 as 'fuck'". Such a translation is called for only when there's been a translation error of the sort analyzed in this post and many earlier posts on this subject.

julie lee said,

September 1, 2013 @ 10:24 am

@QQ:

"Is Victor being overenthusiastic or sarcastic when he translates every instance of 干/幹 as 'fuck'?"

Actually it was not Victor being over-enthusiastic about 干/幹 as 'fuck'. It was Quincy Lu who brought up the subject here. I appreciated the present post because I would have been flummoxed by the use of 幹 (gan) on the menu. I've read VHM's previous post on the subject with interest but had forgotten it (the word never occurs in my own small staid circle), and I appreciated this reminder of "幹 gan"'s off-color meaning. It's good to learn about vulgarisms so that one doesn't use them inadvertently and become a laughing-stock.