New horizons in word sense analysis

« previous post | next post »

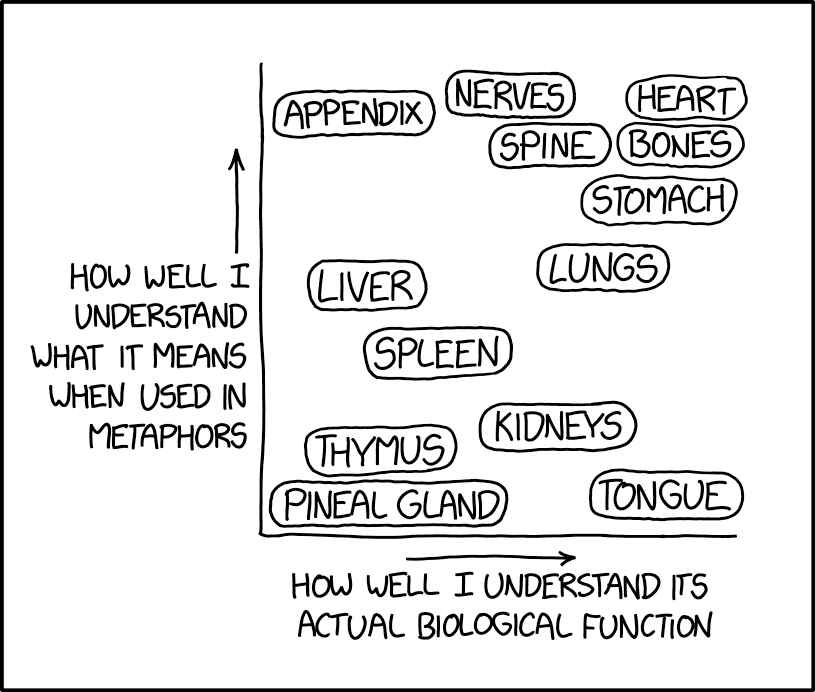

Mouseover title: IMO the thymus is one of the coolest organs and we should really use it in metaphors more."

Like all aspects of word meaning, such metaphors come and go. For example, batshit (in the metaphorical meaning "nonsense" or "crazy") came into use in the middle of the 20th century, presumably via confluence of the older "bats in the belfry" phrase and the proliferation of other (and older) metaphorical "fecal compounds". And medicine has long since left the science of humorism behind, but we've inherited a metaphorical residue when we use phlegmatic to mean "calm, sluggish", or bilious to mean "irascible".

Recent applications of "deep learning" to the analysis of semantic change will open another chapter in the adventure that I described in my 2011 Henry Sweet Lecture, "Towards the Golden Age of Speech and Language Science":

For the sciences of speech and language, the 21st century promises to bring the kind of progress that the 17th century brought to the physical sciences.

Our telescopes and microscopes, our alembics and Pneumatical Engines, are today's vast archives of digital text and speech, along with new analysis techniques and inexpensive networked computation.

However, the scientific use of these new instruments remains mainly exploratory and potential. There are several critical problems for which we have at best partial solutions; and like our 17th-century predecessors, we need to unlearn some old ideas on the way to learning new ones.

Focusing especially on Henry Sweet's own interests in phonetics and in the history of English, this talk will discuss some of the barriers to be overcome, present some successful examples, and speculate about future directions.

Some recent papers (and code) on corpus-based semantic change analysis:

Dominick Schlechtweg et al., "SemEval-2020 task 1: Unsupervised lexical semantic change detection", 2020.

Sinan Kurtyigit et al., "Lexical Semantic Change Discovery", 2021.

Francesco Periti and Stefano Montanelli, "Lexical Semantic Change through Large Language Models: a Survey", 2024.

cameron said,

July 18, 2024 @ 9:15 pm

of course, if we did use "thymus" or "thumos" metaphorically, it'd be seen as a borrowing of the ancient Greek concept of thymos, especially its use in Plato's description of the tripartite soul, and hence not really a metaphor at all

Pedro said,

July 19, 2024 @ 3:03 am

A clever diagram, as always. Odd, though, that Randall has put TONGUE so low on the Y axis – I'd have thought its metaphorical meaning is fairly clear: it usually relates to language or specialised ways of communication.

David L said,

July 19, 2024 @ 9:25 am

What would be a metaphorical use of 'appendix'? The bonus bit at the end of a book is a literal thing-that-is-appended.

Rod Johnson said,

July 19, 2024 @ 1:37 pm

I feel like I've heard "appendix" used in the sense of a vestigial "organ" in some organization, but I can't call an example to mind.

(While I'm thinking about "organ"ization though, there's also "organ" used to mean a periodical publication.)

Peter Taylor said,

July 20, 2024 @ 2:46 am

I'm pretty sure I've seen "appendix" used in some humorous novel to describe someone's boyfriend, in the sense of "useless attachment", possibly even with the suggestion that an appendectomy was required. (And yes, before anyone jumps up to "correct" me, I know that the anatomical appendix isn't actually useless).

Philip Taylor said,

July 20, 2024 @ 4:31 am

Peter — "It sounded like he was just an appendix to her friend and that she just married him after the war because she was depressed that it was all over. Perhaps it …" — from Keeping Watch A WAAF in Bomber Command.

Cervantes said,

July 20, 2024 @ 10:33 am

Of course the cartoonist's understanding of biological function is what it is, but some of the placements on the metaphor axis do seem odd. I certainly can't see liver being higher than both tongue and spleen. In fact tongue might be used metaphorically as often as it is literally, whereas it's hard to think of a metaphorical use for liver.

Philip Taylor said,

July 20, 2024 @ 12:51 pm

Well, the OED (2nd. edn) attests to a non-literal usage :

Breffni said,

July 20, 2024 @ 3:30 pm

Given that testy is from Anglo-French teste ‘head’, a hearty Earl who’s testy when liverish has an awful lot going on physio-affectively.

JPL said,

July 20, 2024 @ 4:10 pm

@Cervantes: "… it's hard to think of a metaphorical use for liver."

I don't know about English, but Sierra Leone Krio has an expression, "i geh liba" (lit. "she/he has liver"), whose sense could be understood with the translation not-quite-equivalent, "She/he has the audacity!".

Peter Taylor said,

July 21, 2024 @ 1:40 am

@JPL, similar to gall in English? Although that particular sense of gall is only attested from 1882 in OED.

Rakau said,

July 21, 2024 @ 2:50 am

How about “lily livered”. Not uncommon in Aotearoa New Zealand to mean cowardly or gutless (another anatomical metaphor}.

Philip Taylor said,

July 21, 2024 @ 5:02 am

Not uncommon in the UK either, Rakau, although it is now some time since I last heard it used or read it in print …

Cervantes said,

July 21, 2024 @ 7:25 am

Well "2. colloq. Having the symptoms attributed to disordered liver" is not metaphorical, it's entirely literal. The other examples are not from English, for the most part, although lily livered is familiar. Still, much less common than the innumerable metaphorical uses of tongue. Tongue bath, tongue lashing, tongues of fire, and of course tongue as language. . . .

Spleen is used to mean ill-temper or anger, in various ways, because of the archaic humoral theory of temperament and disease. The spleen was thought to be the source of (the non-existent) black bile. This usage was originally literal, so whether it's fair to call it metaphorical now that we no longer believe in that theory is debatable, I suppose. I would presume, though I haven't researched it, that the idea of the liver as somehow associated with courage is based on a similar obsolete theory.

Philip Taylor said,

July 21, 2024 @ 8:01 am

Well, I see the sense in your argument, Cervantes (in re "liverish") but would you therefore argue that when we say that a woman is hysterical, we are not using the term metaphorically but literally, in that her hysteria is attributable to her womb ? For myself, I think that the two are analogous — we may well say "liverish" even when we are certain that a malfunctioning liver is not the root cause in just the same way as we might say "hysterical" knowing full well that the womb is not implicated …

Andreas Johansson said,

July 23, 2024 @ 3:23 pm

The cases are non-analoguous in that probably most people who use "hysterical" do not know the word is anything to do with the womb.

/df said,

July 25, 2024 @ 5:35 pm

Also, anyone who has suffered a liver infection can attest to the literal effects that are enshrined in the word "liverish".