Hendiadys and sleeping in parks

« previous post | next post »

Samuel Bray, "Cruel AND Unusual?", Reason 4/21/2024:

On Monday, the Supreme Court will hear argument in an Eighth Amendment case, City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Johnson. One thing I will be watching for is whether the justices in their questions treat "cruel and unusual" as two separate requirements, or as one.

The Eighth Amendment (to the U.S. Consitution) says that "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

And the issue in the cited Supreme Court case is "Whether the enforcement of generally applicable laws regulating camping on public property constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment." (More here, here, and elsewhere…)

Samuel Bray's interest in the interpretation of "cruel and unusual" follows up on his 2016 Virginia Law Review article, "'Necessary and Proper' and 'Cruel and Unusual': Hendiadys in the Constitution", Va. L. Rev. (2016):

This Article attempts to shed new light on the original meaning of the Necessary and Proper Clause, and also on another Clause of the U.S. Constitution, the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The phrases “necessary and proper” and “cruel and unusual” can be read as instances of an old but now largely forgotten figure of speech. That figure is hendiadys, in which two terms separated by a conjunction work together as a single complex expression.

A bit more of that article's argument:

First consider “cruel and unusual.” These are often understood as two separate requirements: punishments are prohibited only if they are cruel and unusual. Yet this phrase can easily be read as a hendiadys in which the second term in effect modifies the first: “cruel and unusual” would mean “unusually cruel.” When this reading is combined with the work of Professor John Stinneford, which shows that “unusual” was used at the Founding as a term of art for “contrary to long usage,” it suggests that the Clause prohibits punishments that are innovatively cruel. In other words, the Clause is not a prohibition on punishments that merely happen to be both cruel and innovative. It is a prohibition on punishments that are innovative in their cruelty.

You can read the rest for yourself…

The Wikipedia page explains that the origin of the word hendiadys is the Greek phrase ἓν διὰ δυοῖν "one through two".

One of the OED's earliest citations is to Angell Day's 1592 English Secretorie (revised edition) — the first edition was printed in 1586, which would make it the earliest citation.

Project Gutenberg has a transcription of the 1599 edition, in which the relevant definition reads

Hendiadis, when one thing of it selfe intire, is diuersly layde open, as to saie, On iron and bit he champt, for on the iron bitte hee champt: And part and pray we got, for part of the pray: Also by surge and sea we past, for by surging sea we past. This also is rather Poeticall then other wise in vse.

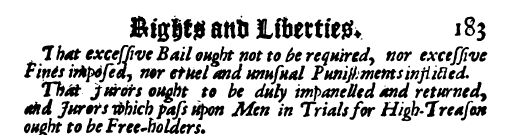

I'm not familiar with the literature on the wording of the Bill of Rights, so maybe this is common knowledge — but a quick Google Books search reveals that the section on "Rights and Liberties" in this 1696 book lists a 1688 act of Parliament that contains (along with many other principles) almost exactly the wording of the Eighth Amendment:

Whereas the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons assembled at Westminster, lawfully, fully and freely representing all the Estates of the People of this Realm, did upon the 13th day of February in the year of our Lord One thousand six hundred eighty eight, present unto their Majesties, then called and known by the Names and Stile of William and Mary, Prince and Princess of Orange, being present in their proper Persons, a certain Declaration in Writing, made by the said Lords and Commons in the Words following, viz.

[… lots of stuff omitted …]

That excessive Bail ought not to be required, nor excessive Fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual Punishments inflicted.

Martin Holterman said,

April 22, 2024 @ 5:12 pm

As a matter of complete coincidence, that 1688/1689 Act of Parliament is also called the "bill of rights".

J.W. Brewer said,

April 22, 2024 @ 5:20 pm

There's that well-known quotation attr. Anatole France which in the translation I'm most familiar with says in part "'The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges …" Which tends to suggest that at least in French historical practice "the enforcement of generally applicable laws regulating camping on public property" is neither cruel nor unusual, making it unnecessary to reach the issue of whether "and" should be read in this context as "or."

There was, by the way, a different case decided last month by the Supreme Court on how to interpret "and" in a particular statutory context. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/22-340_3e04.pdf I thought Justice Gorsuch's dissent was more grammatically plausible than Justice Kagan's majority opinion, but that was based on a fairly quick skim and I might have different views if I'd put more time into a more thorough analysis. The dissent but not the majority opinion referenced the corpus-linguistics based amicus brief of Professor* Thomas R. Lee et al., which can be found here: https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/22/22-340/267866/20230526173841166_22-340%20Amicus%20Brief%20Professors%20Final.pdf

*Now-Professor Lee has completed his tenure as Justice Lee of the Utah Supreme Court, during which he was substantially more interested in arguments based on corpus linguistics than the typical American jurist.

Seth said,

April 22, 2024 @ 10:43 pm

I don't think "innovatively cruel" makes sense as a meaning. There's plenty of punishments which are known from centuries past which are extremely cruel, but hardly can be termed "innovative" since they are well-known. I find it hard to believe it would be Consitutionally acceptable to, e.g. boil someone alive, on the basis that it may be cruel but it's classic (well, maybe with the current Supreme Court …).

https://www.britannica.com/story/cruel-and-unusual-punishments-15-types-of-torture

My view is "unusual" here means more like "excessively cruel", as all more than trivial punishment can be argued to be cruel in some sense. But stuff like boiling in oil is on an entirely different level.

J.W. Brewer said,

April 22, 2024 @ 11:46 pm

The simplest and most easily-administered interpretation of "cruel and unusual" would focus on historically-attested modes of punishment that had already fallen out of use in England because of their perceived barbarism by either 1689 (when the above-referenced statute was enacted in the wake of the soi-disant Glorious Revolution) or 1789 (when the Eighth Amendment was put forth for ratification in the U.S. after a different revolution). But the U.S. Supreme Court has been more ambitious than that, and has not-unrelatedly over time bollixed up the doctrine quite badly. This particular case turns out upon further inquiry to be an after-effect of a very poorly-reasoned (IMHO) 1962 decision where a quite dubious-seeming California statute was perhaps justly struck down, but cruel-and-unusual-punishment was almost certainly not the most sensible ground on which to do so even though that was the thin reed the majority latched onto. 1962 fell during a historical period in which rather a lot of Supreme Court decisions that reached plausible-seeming outcomes got there via a lot of sloppy handwaving rather than thoughtful doctrinal reasoning, but the precedent is on the books. The 1962 decision is indeed so sloppy that one cannot imagine any of the justices who signed on to it being particularly interested in hearing about the possible relevance of hendiadys as an interpretive lens. Even though some of them had probably had what by the debased standards of the 21st century would seem a pretty good classical education.

David Marjanović said,

April 23, 2024 @ 4:49 am

Did or actually mean OR at the time, as it does now, or did it mean XOR, as the nearest equivalents in other European languages tend to do? I've always taken for granted that "cruel and unusual" means that cruel punishments and unusual punishments are both forbidden, because that's the simplest interpretation in German…

David Marjanović said,

April 23, 2024 @ 4:57 am

…That may have been too terse. Nowadays, the most straightforward way to express that cruel punishments and unusual punishments are both forbidden would be to use "cruel or unusual", so people tend to think that "cruel and unusual" must mean something else in such an important legal document. I'm wondering if that was already how things worked at the end of the 18th century, because using und here in German (for example) would be the most straightforward way to express that cruel punishments and unusual punishments are both forbidden, while oder would be somewhat confusing.

Stephen Goranson said,

April 23, 2024 @ 7:31 am

This reminds me of rabbinic commentaries on Deuteronomy 21:18 and following (RSV):

“If a man has a stubborn and rebellious son, who will not obey the voice of his father or the voice of his mother, and, though they chastise him, will not give heed to them, 19 then his father and his mother shall…."

How many of these specifications are required?

J.W. Brewer said,

April 23, 2024 @ 10:10 am

The recent academic paper you can find via the link at the bottom of this comment gives a pretty lengthy account/compilation of what various actors (including but not limited to judges) thought "cruel and unusual" meant in this context from late 17th-century England through late 19th-century America. They didn't all agree, but perhaps it's fair to say that the rival views fell within a certain range with discernible outer boundaries, with some more recent judicial decisions straying outside that range.

One funny tidbit on "and" v. "or" that I don't think I previously knew. Before the federal Constitution was adopted many but not all of the new state constitutions added language proscribing cruel and unusual punishments because it was in the English Bill of Rights and sounded good etc. The Articles-era Congress did more or less the same when promulgating the Northwest Ordinance shortly before the drafting of the Constitution got underway, but instead proscribed "cruel or unusual" punishments, perhaps inadvertently, but offering some evidence that people were not necessarily focused on "and" versus "or" as crucial to understanding what the phrase meant.

I don't know the history myself in enough to detail to be confident that it's a full and fair presentation of the historical evidence and don't know much about the author, but nothing about the presentation feels like a "tell" that something's likely being distorted or slanted (and I have read plenty of legal-academic scholarship where you could get that vibe from a presentation of remote history even if you didn't know the details well enough to know what was being mischaracterized or omitted). I have not even skimmed the end section of the paper where the author offers some sort of proposal about what the courts should be doing going forward in light of all this evidence.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4684527

Mike Grubb said,

April 23, 2024 @ 10:12 am

@David Marjanović: I don't think XOR works in practice for parsing "cruel and unusual," because, for example, sentencing someone to mandatory anger management counseling or drug rehab would have, at one time, been "unusual," but not been perceived as "cruel," and, to my (admittedly limited) knowledge, no such sentences have been overturned on the basis of violating the "cruel and unusual" prohibition. Cruelty would seem to be a necessary condition; "unusualness," in and of itself, not so much.

Buzz79 said,

April 23, 2024 @ 10:50 am

In the preamble to the quoted parliamentary statue you will find "Lords Spiritual and Temporal". This quite obviously refers to the peers of the realm and the lords of the Church of England as two separate groups. There are other uses of and in the same passage (fully and freely, called and known, names and stile, etc.) all of which refer to either separate categories or two names for the same concept. None of them indicate that one of the linked terms modifies the other. It seems entirely logical to me to interpret "cruel and unusual" in the same way as two separate categories of punishments that are prohibited. Unless, of course, one was stretching to narrow the scope of a passage that one dislikes for other reasons.

J.W. Brewer said,

April 23, 2024 @ 12:58 pm

@Buzz79: I would suggest that the syntax of conjunctions often works differently in the context of prohibitions than it does in your examples. Compare:

a. "don't drink and drive," which does not bar you from drinking without driving or driving without drinking, with

b. "thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour's," which tells you not to do any of the various things on the list even if you refrain from the others.

Or consider this statute defining a particular misdemeanor under present New York law:

A person is guilty of issuing a bad check when:

1. (a) As a drawer or representative drawer, he utters a check knowing

that he or his principal, as the case may be, does not then have

sufficient funds with the drawee to cover it, and (b) he intends or

believes at the time of utterance that payment will be refused by the

drawee upon presentation, and (c) payment is refused by the drawee upon

presentation; or

2. (a) He passes a check knowing that the drawer thereof does not then

have sufficient funds with the drawee to cover it, and (b) he intends or

believes at the time the check is passed that payment will be refused by

the drawee upon presentation, and (c) payment is refused by the drawee

upon presentation.

Note how the "ands" and the "or" work together. The prosecution can establish guilt by proving either 1 or 2, but for whichever approach it chooses it must prove all three of elements (a), (b), and (c).

That said, "cruel and unusual punishments" in this case is a fixed phrase, apparently not extant prior to 1688, so it may have or have evolved an idiomatic meaning that cannot be fully ascertained by usual syntactic analysis.

cameron said,

April 23, 2024 @ 2:12 pm

I remember reading the obituary of actor Richard Herd a few years ago, and noting that he had attended a school in Boston called the Industrial School for Crippled and Deformed Children.

my reaction was "crippled AND deformed"? they certainly had very selective admission criteria

they also really knew how to name a school back then

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/28/arts/television/richard-herd-dead.html

Mark Roy said,

April 24, 2024 @ 8:58 am

I always understood it to be neither cruel (torture) nor unusual (made to eat dog feces). Incarceration was meant to be punishment, not a sadistic game. So I'd say both the cruel and the unusual are ruled out independently. I don't know the details of the post-Constitutional practice, but this seems to be a rejection of the stocks/tar-and-feathers school of judicial punishment. I wouldn't overthink the semantic possibilities beyond that.