Q. Pheevr's Law again

« previous post | next post »

A few days ago, a journalist asked me for an interview about Donald Trump's rhetoric, "to discuss the style of his campaign events, the role his rhetoric plays in them, and why they’ve been an effective tool for him". In preparation, I made a list of past LLOG posts about Trump's rhetorical style,, and I'll post the whole (shockingly long) list later on, with the attempt at a summary that I prepared for the interview. Clearly I've joined the rest of the world in being drawn in by Trump's attention-seeking techniques — but that's not the point of this post.

One of the hundreds of posts in my list was "Q. Pheevr's Law", 5/17/2016. The background was an earlier post about modificational anxiety, "Adjectives and Adverbs", where Q.Pheevr had suggested in the comments that

it looks as if there could be some kind of correlation between the ADV:ADJ ratio and the V:N ratio (as might be expected given that adjectives canonically modify nouns and adverbs canonically modify verbs)

I tested this idea, and found a striking relationship — with an interesting stylistic footnote about the debate transcripts of some politicians, including Donald Trump.

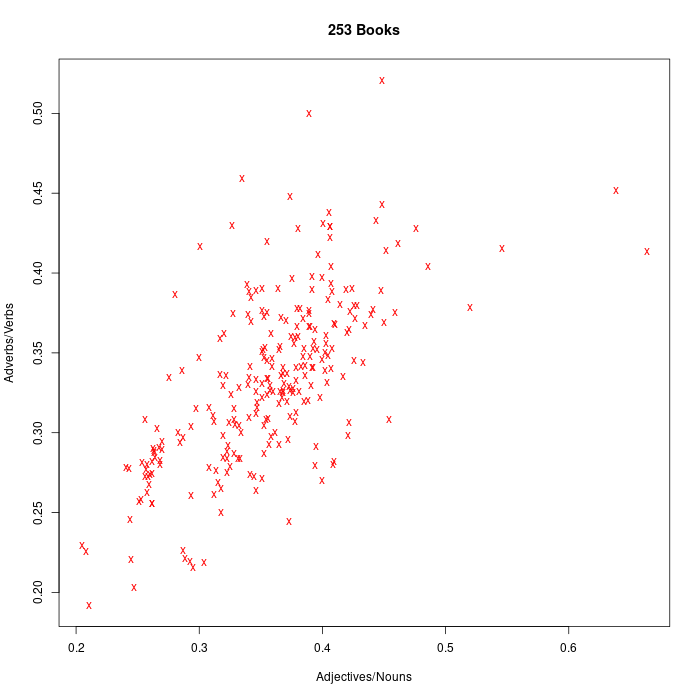

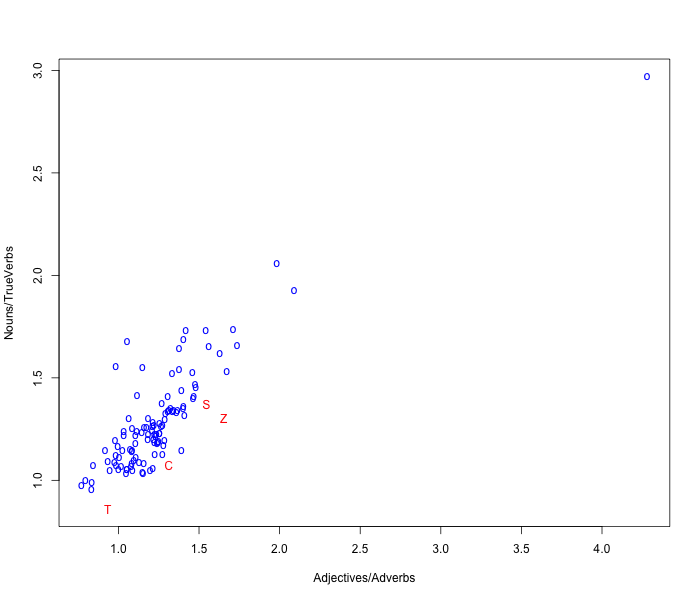

Here's the plot from that 2016 post:

The correlation is r=0.870. The point in the upper-right corner is the U.S. Constitution. The point in the lower-left corner is Peter Pan.

The red letters are the number for four politicians, calculated from their debate transcripts: Trump=T, Clinton=C, Sanders=S, Cruz=Z). So Donald Trump is most like Peter Pan, while Bernie Sanders and Ted Cruz are (stylistically) a bit more like the U.S. Constitution…

After some poking around, including asking some colleagues as well as searching Google Scholar, I concluded that the suggested relationship had not been noticed before, much less studied — and so I suggested calling it Q. Pheevr's Law.

Over the intervening years, I've forgotten about it, but it still seems unstudied.

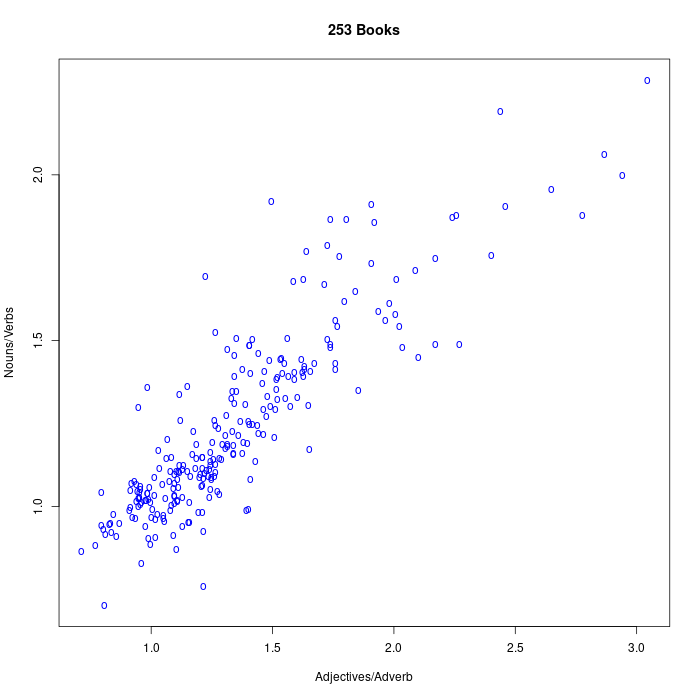

So for this morning's Breakfast Experiment™ I decided to confirm the relationship, with a more modern P.O.S. tagger and a somewhat larger set of book texts (but omitting the Constitution). The correlation for this dataset is r=0.88:

Interestingly, the relationship between Adjective/Noun ratio and Adverb/Verb ratio is noticeably less crisp (r=0.66):

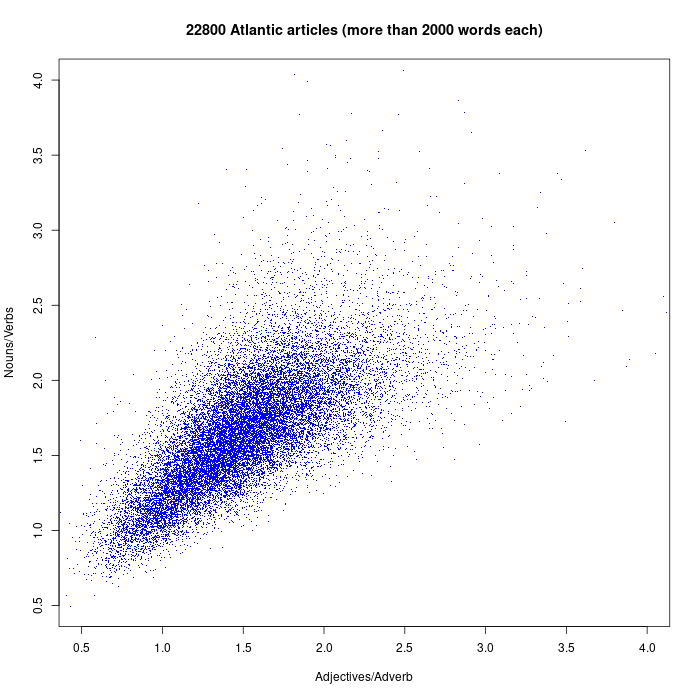

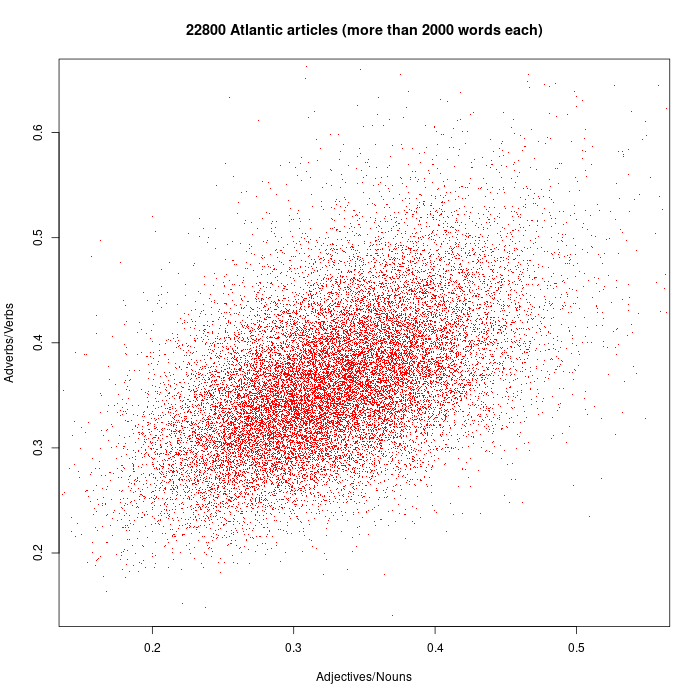

And I did the same thing with 22,800 articles from a copy of the Atlantic Magazine Archive. I included only the articles more than 2000 words long, in order to keep down noise and also because many of the short articles are linguistically atypical in various ways:

The pattern is more diffuse (r=0.71). Presumably this is partly because each text is shorter, and partly because of a larger stylistic range, including poems, lists, and so on. Similarly for the relationship between Adjective/Noun ratio and Adverb/Verb ratio (r=0.52), where the (still significant) correlation is again weaker:

All this reinforces that original questions: Why the relationship, and what stylistic dimension(s) does it reveal?

Andy said,

December 30, 2023 @ 1:05 pm

I would suggest, as you're plotting ratios against each other, then a log scale in both directions may be better. It would possibly also help with the outliers in the top right in the initial plots.

david said,

December 30, 2023 @ 1:19 pm

What about this?…

It looks like the slope of the adj/adv-vs-noun/verb regression line is 1-ish, if I'm interpreting this correctly. Let's call increased use of adjectives or adverbs "flowery language" (only for want of a descriptive term, not in any pejorative sense).

Doesn't the nearness of the regression to 1 suggest that writing styles tend be equally flowery for both "things" (nouns) and "actions" (verbs)? Thus, if people tend to write in a flowery fashion, they do so equally for both things and actions, and if they lean to non-flowery writing, they write that way equally for both things and actions.

Consequence: flowery writing does not discriminate between decorations of "things" or "actions".

Perhaps the more diffuse distributions of the ratios taken the other way suggest that the data are less clear about a preference for talking about "things" vs talking about "actions".

Mark Liberman said,

December 30, 2023 @ 4:15 pm

@Andy: "I would suggest, as you're plotting ratios against each other, then a log scale in both directions may be better."

That's sensible, but it doesn't make a lot of visible difference in this case:

The correlations are also similar, FWIW: 0.87 for the first plot, 0.69 for the second.

You're right that it might make more difference if noun- and adjective-heavy (or verb- and adverb-light) texts like the Constitution were included…

Mark Liberman said,

December 30, 2023 @ 4:27 pm

@David: "Doesn't the nearness of the regression to 1 suggest that writing styles tend be equally flowery for both "things" (nouns) and "actions" (verbs)? Thus, if people tend to write in a flowery fashion, they do so equally for both things and actions, and if they lean to non-flowery writing, they write that way equally for both things and actions."

The slope is somewhat less than 1. And the proposed explanation needs the additional clause that the balance between nominal and verbal phrasing can vary. Then if the rate of modification on either side remains the same, the observed relationship of ratios would be generated (though I haven't thought through the relevant models carefully…).

D.O. said,

December 30, 2023 @ 9:33 pm

Back at the time of the first post, I have analyzed the Brown corpus and found that under PCA the main difference in texts is indeed between (noun + adj) vs. (verb + adv) followed by "floweriness" (adj+adv) vs. (noun+verb). Can find those PCA coefficients if someone is interested. Another observation (if I recall correctly) was that fiction tended to be on the "verbie" side of the distribution while the rest (news, non-fic, government, academic) were more or less similar (and to the "nouny" side, of course, it's all relative).

Looking at outliers were nouns*adv/(verb*adj) are very different from the average (mean of log is 0.35, which means that verbs like to dress up with adverbs about 1.4 times less than nouns with adjectives), I see 4/10 texts tagged as "news", 5/10 is fiction, and 1/10 is learned on the lots of adjective not much adverbs side and 5/10 "government, and "learned", "lore", "belles-lettres","editorial", and "hobbies" at 1/10 each on the other side. So basically, news and fiction tend to embellish themselves with adjectives and officialese and non-fiction like adverbs above and beyond.