Corporeal grammar

« previous post | next post »

Recent article in Scientific American:

This Ancient Language Has the Only Grammar Based Entirely on the Human Body

An endangered language family suggests that early humans used their bodies as a model for reality

By Anvita Abbi on June 1, 2023

From just a small handful of Andaman Islanders, the last speakers of their languages, Anvita Abbi was able to piece together what she believes to be the basic principles of their grammar. What she found was astonishing. Keep your antennae up and out, however, because her article begins with the much debunked story of how thousands of the indigenous people escaped death when the devastating tsunami of December 26, 2004 struck their islands by relying on the deep, autochthonous knowledge bequeathed by their ancestors, although she does not directly attribute their actions to the grammatical features of their language as many popularizers had done at the time of the disaster (see "Selected readings" below), but rather, more sophisticatedly, to the wisdom transmitted over thousands of generations through their mother tongue.

…

A language embodies a worldview and, like a civilization, changes and grows in layers. Words or phrases that are frequently used morph into ever more abstract and compressed grammatical forms. For instance, the suffix “-ed,” signifying the past tense in modern English, originated in “did” (that is, “did use” became “used”); Old English's in steed and on gemong became “instead” and “among,” respectively. These kinds of transitions make historical linguistics rather like archaeology. Just as an archaeologist carefully excavates a mound to reveal different epochs of a city-state stacked on one another, so can a linguist separate the layers of a language to uncover the stages of its evolution.

…

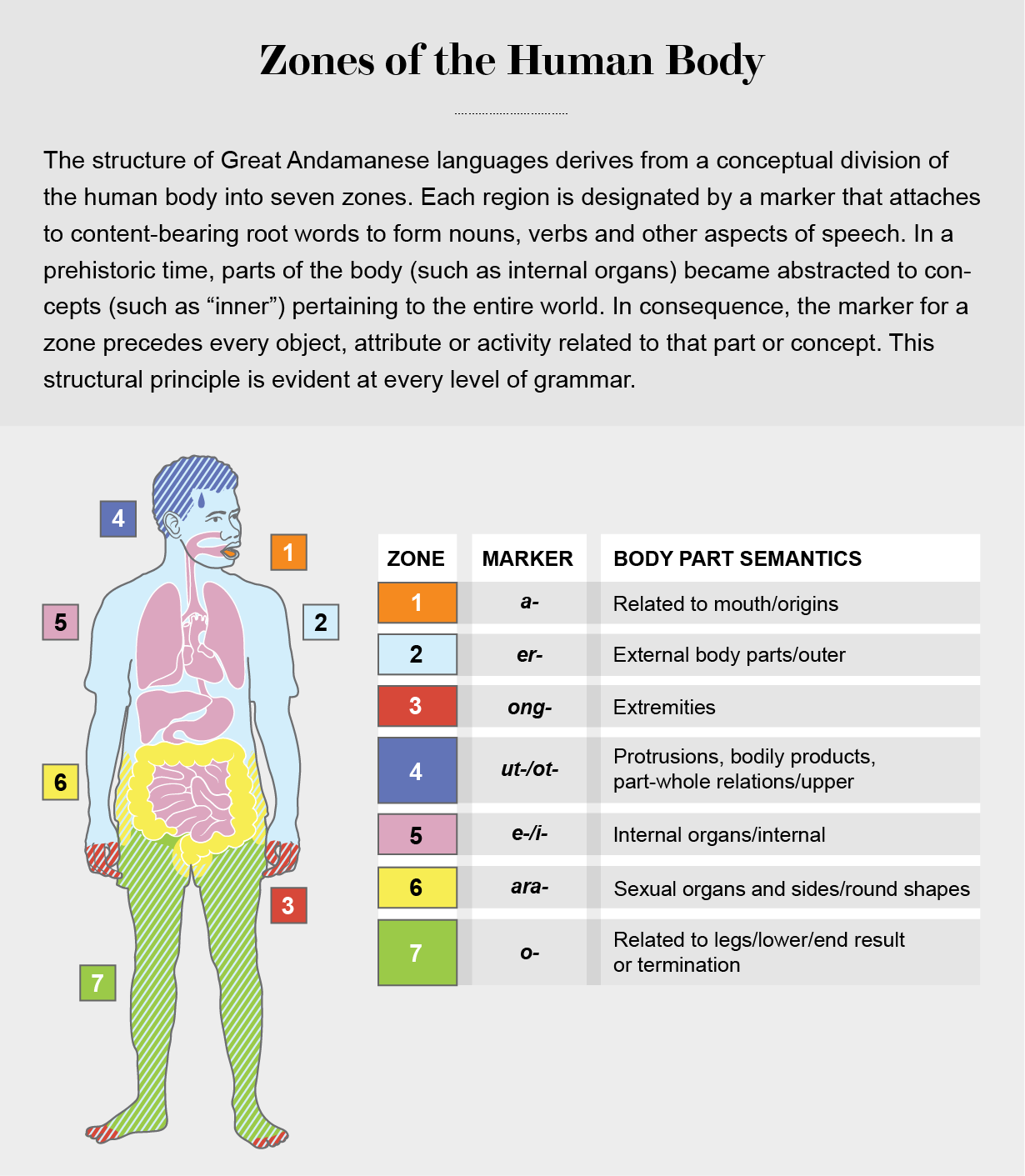

Great Andamanese, it turns out, is exceptional among the world's languages in its anthropocentrism. It uses categories derived from the human body to describe abstract concepts such as spatial orientation and relations between objects. To be sure, in English we might say things like “the room faces the bay,” “the chair leg broke” and “she heads the firm.” But in Great Andamanese such descriptions take an extreme form, with morphemes, or meaningful sound segments, that designate different zones of the body getting attached to nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs—indeed, to every part of speech—to make diverse meanings. Because no other known language has a grammar based on the human body or shares cognates—words that are similar in meaning and pronunciation, indicating a genealogical connection—with Great Andamanese, the language constitutes its own family.

The most enduring aspect of a language is its structure, which can persist over millennia. My studies indicate that the Great Andamanese were effectively isolated for thousands of years, during which time their languages evolved without discernible influence from other cultures. Genetic research corroborates this view, showing that these Indigenous people descend from one of the first groups of modern humans to migrate out of Africa. Following the coastline of the Indian subcontinent, they reached the Andaman archipelago perhaps 50,000 years ago and have lived there in virtual isolation ever since. The core principles of their languages reveal that these early humans conceptualized the world through their bodies.

…

British officials had observed that the Andamanese languages were a bit like links in a chain: members of neighboring Great Andaman tribes understood one another, but those speaking languages at opposite ends of the chain, in North and South Andaman, were mutually unintelligible. In 1887 British military administrator Maurice Vidal Portman published a comparative lexicon of four languages, as well as a few sentences with their English translations. And around 1920 Edward Horace Man compiled an exhaustive dictionary of Bea, a South Andaman language. These were significant records, but neither cracked the puzzle the grammar posed.

Nor could I. Somehow my extensive experience with all five Indian language families [VHM: Indo-European, Dravidian, Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, and Tai-Kadai] was no help.

The author goes on to describe how, through many visits to the island and detailed questions put to her informants, she gradually discerned the distinctive properties of their language and pieced together its grammar.

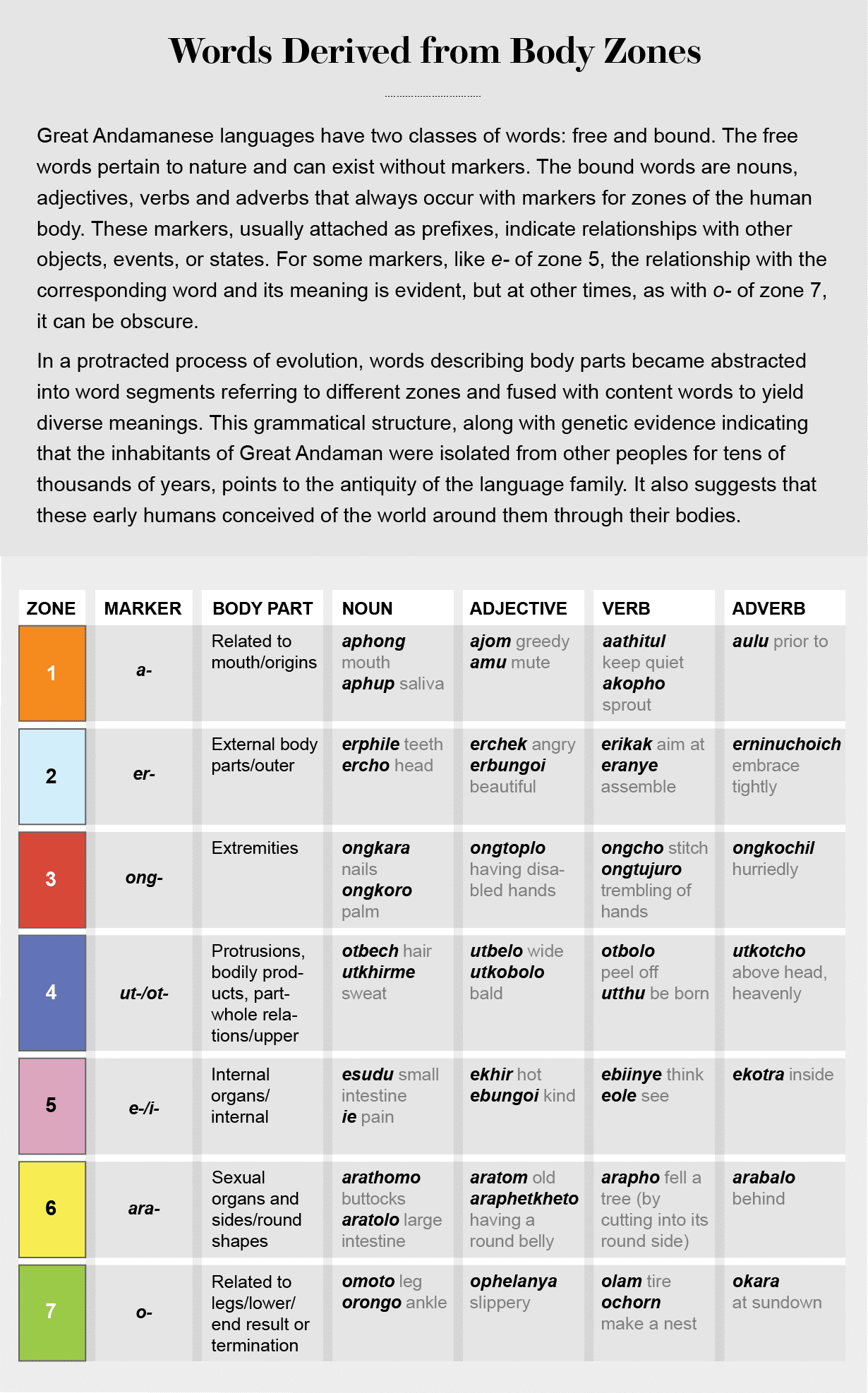

The grammar I was piecing together was based primarily on Jero, but a look through Portman's and Man's books convinced me that the southern Great Andamanese languages had similar structures. The lexicon consisted of two classes of words: free and bound. The free words were all nouns that referred to the environment and its denizens, such as ra for “pig.” They could occur alone. The bound words were nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs that always existed with markers indicating a relation to other objects, events or states. The markers (specifically, a-; er-; ong-; ot-or ut-; e-or i-; ara-; and o-) derived from seven zones of the body and were attached to a root word, usually as a prefix, to describe concepts such as “inside,” “outside,” “upper” and “lower.” For example, the morpheme er-, which qualified most anything having to do with an outer body part, could be stuck to -cho to yield ercho, meaning “head.” A pig's head was thus raercho.

This conceptual dependency did not always indicate physical attachment. For example, if the pig's head were cut off for roasting, the marker t- for an inanimate object would be attached to er- to yield ratercho; it was no longer alive but still a pig's head. The suffix -icho indicated truly separable possessions. For example, Boa-icho julu meant “Boa's clothes.”

Just as a head, a noun, could not conceptually exist on its own, the mode and effect of an action could not be severed from the verb describing the action. Great Andamanese had no words for agriculture or cultivation but a great many for hunting and fishing, mainly with a bow and arrow. Thus, the root word shile, meaning “to aim,” had several versions: utshile, to aim from above (for example, at a fish); arashile, to aim from a distance (as at a pig); and eshile, aiming to pierce.

Also inseparable from their prefixes, which endowed them with meaning, were adjectives and adverbs. For example, the prefix er-, for “external,” yielded the adjective erbungoi, for “beautiful”; the verb eranye, meaning “to assemble”; and the adverb erchek, or “fast.” The prefix ong-, the zone of extremities, provided ongcho, “to stitch,” something one did with fingers, as well as the adverb ongkochil, meaning “hurriedly,” which usually applied to movements involving a hand or foot. Important, too, was the morpheme a-, which referred to the mouth and, more broadly, to origins. It contributed to the nouns aphong, for “mouth,” and Aka-Jero, for “his Jero langauge”; the adjectives ajom, “greedy,” and amu, “mute”; the verbs atekho, “to speak,” and aathitul, “to keep quiet”; and the adverb aulu, “prior to.”

These studies established that the 10 original Great Andamanese languages belonged to a single family. Moreover, that family was unique in having a grammatical system based on the human body at every structural level. A handful of other Indigenous languages, such as Papantla Totonac, spoken in Mexico, and Matsés, spoken in Peru and Brazil, also used terms referring to body parts to form words. But these terms had not morphed into abstract symbols, nor did they spread to every other part of speech.

Credit: Anvita Abbi, styled by Scientific American

Most significant, the language family seems to be truly archaic in origin. In a multistage process of evolution, words describing diverse body parts had changed into morphemes referring to different zones and fused with content words to yield meaning. Along with the genetic evidence, which indicates the Great Andamanese lived in isolation for tens of thousands of years, the grammar suggests that the language family originated very early—at a time when human beings conceptualized their world through their bodies. The structure alone provides a glimpse into an ancient worldview in which the macrocosm reflects the microcosm, and everything that is or that happens inextricably connects to everything else.

…

In the Great Andamanese view of nature, the foremost distinction was between tajio, the living, and eleo, the nonliving. Creatures were tajio-tut-bech, “living beings with feathers”—that is, of the air; tajio-tot chor, “living beings with scales,” or of the water; or tajio-chola, “living beings of the land.” Among the land creatures, there were ishongo, humans and other animals, and tong, plants and trees. These categories, along with multiple attributes of appearance, motion and habits, made for an elaborate system of classification and nomenclature that I documented for birds in particular. Sometimes the etymology of a Great Andamanese name bore a resemblance to the English one. For example, Celene, made up of root words for “crab” and “thorn,” was so named because it cracks and eats crabs with its hard, pointed beak.

…

Things get pretty heady when Abbi delves into the non-Einsteinian relativity of the Andamese concept of time:

Time, too, was relative, categorized according to natural events such as the blossoming of seasonal flowers, the availability of honey—the honey calendar, one might call it—the movement of the sun and the moon, the direction of winds, the availability of food resources, and the best time for hunting fish or other animals. Thus, when the koroiny auro flower blooms, the turtles and fish are fat; when the bop taulo blooms, the bikhir, liot and bere fish are abundant; when the loto taulo blooms, it is the best time for catching phiku and nyuri fishes; and when the chokhoro taulo blooms, the pigs are at their fattest, and it is the best time to hunt them.

Even “morning” and “evening” were relative, depending on who experienced them. To say, for instance, “I will visit you tomorrow,” one would use ngambikhir, for “your tomorrow.” But in the sentence “I will finish this tomorrow,” the word would be thambikhir, “my tomorrow.” Time depended on the perspective of whoever was involved in the event.

Abbi ends her article on an elegiac note: "Of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken by humans today, half will fall silent by the end of this century." The author has commendably done her part to preserve the legacy of at least one of those fast dying languages.

PDF of Abbi's article available here.

Selected readings

- "Professional Foolishness" (4/18/04)

- "Can relationships between languages be determined after 80,000 years?" (6/10/04)

- "Pronouns are like sweaters: Kusunda revisited" (6/13/04)

- "No word for 'lazy hack parroting drivel'?" (4/1/05)

- "'60 Minutes' doomed to repeat itself" (12/24/05)

- "Nias, Komodo, and 'Kong'" (1/09/06)

- "Grammar, time, and truth" (4/18/11)

[Thanks to Hiroshi Kumamoto]

Ben Zimmer said,

September 26, 2023 @ 4:19 pm

It's disappointing that Scientific American went with the "ancient language" angle in the headline, but I guess it's just following the lead of the "ancient worldview" angle in the article.

Victor Mair said,

September 26, 2023 @ 7:57 pm

From Michael Witzel:

Please see my older paper on the Andamanese numeral system (tallying) from head to fingers (16 spots) and then back (with “ablaut").

Michael Witzel, "The Numeral System of Jarawa Andamanese", unpublished paper, drawing on R. Senkuttuvan, The Language of the Jarawa (Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India, 2000), pp. iv, 57.

Jonathan Mayhew said,

September 27, 2023 @ 10:44 am

Whorfism… It is interesting that we don't view catachresis in our own language as evidence of a deeply ancient world view, as in heading a committee, handing off a football, or facing the facts (or other examples cited here).

Benjamin Ernest Orsatti said,

September 27, 2023 @ 12:28 pm

Jonathan,

I know it's not fashionable to say that the manner by which different languages carve up reality affects the thoughts of the speakers of those languages, but don't you think it could a little?

For example, isn't it likely that speakers of languages with noun classes (e.g., Bantu https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luganda#Noun_classes) do see common members of those classes as having something in common? A Luganda speaker, say, might see a connection between a dog and a chair (em-bwa and en-tebbe — both Class III nouns) that doesn't exist between a dog (C. III) and a book (eki-tabo — Class IV noun).

Or, put differently, how "strong" of an anti-Whorfian are you? In other words, if you'd suddenly forgotten how to speak English and had to learn a new language with which to discuss ontology and epistemology, would Navajo be just as good as Latin?

— Ben

Jonathan Mayhew said,

September 27, 2023 @ 9:18 pm

I'm pretty strong in anti-Whorfism, but open minded. Obviously it is easy to talk about Greek philosophy in Greek, because the vocabulary already exists for that in that language. I guess Latin would be good too, since they learned philosophy from Greek tutors.

My main idea is that I don't experience why own language as a world view. I don't think of of a disease as a "dis-ease" or lack of comfort. I don't experience breakfast as breaking of a fast. It could just be a petit dejeuner.

Chas Belov said,

September 27, 2023 @ 10:50 pm

…or Navajo philosophy in Navajo

Peter Grubtal said,

September 28, 2023 @ 3:59 am

the suffix “-ed,” signifying the past tense in modern English, originated in “did” (that is, “did use” became “used”)

Is this correct? The t/d past endings with weak verbs is matched in German, and even in Latin we have past participles in "t" : amatum etc. This suggests a deeper IE root of this characteristic.

Benjamin Ernest Orsatti said,

September 28, 2023 @ 7:33 am

Linguistics is so frustrating; it's like it's got one foot firmly planted in the sciences and the other in the humanities. There are "rules" and "laws" and "hypotheses", but they're not really testable. So, you can't go out and gin up an experiment to tease apart the linguistic versus acculturated influences on cognition. (Can you? If so, send link to paper!).

It _seems_ right to say that I'm not thinking about breaking a fast this morning any more than Mme. Dupont is thinking about her little lunch as such, but I don't know why.

And yes, I don't think the vast palate of nominal and verbal Latin inflections would aid much in sussing out Navajo philosophy, but is that because of culture or language?

I'll just keep repeating to myself, "Correlation is not causation"…

ktschwarz said,

September 28, 2023 @ 8:02 pm

Peter Grubtal: The article's phrasing is little imprecise; more precisely, the English past tense suffix -ed is inherited from Proto-Germanic (with cognates in most Germanic languages), and is generally thought to have originated there, from the past form of a verb ancestral to "do". However, one alternative theory is that it came from a PIE ending that is also the source of the -t- in many Latin past participles.

Summarized from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanic_weak_verb#Origin_of_dental_suffix

Jonathan Smith said,

September 28, 2023 @ 8:47 pm

maybe not Whorfism so much as the implication that the language has persisted little-changed for 50 millennia ("they reached the Andaman archipelago perhaps 50,000 years ago and have lived there in virtual isolation ever since. The core principles of their languages reveal that these early humans conceptualized the world through their bodies"), most unlikely given the nature of the "Body Zones" table and anyway a basic violation of the Uniformitarian Principle.

Michael Watts said,

September 28, 2023 @ 10:51 pm

I thought I had read that past tenses formed with a suffix identical in form to the fully-conjugated verb to do were attested in Gothic, and that was why we believe the English past-tense suffix arose in that way?

But that's not really compatible with the idea that the suffix, and no longer the full verb, was already a feature of proto-Germanic.

On an unrelated note, I've been thinking about this sentence:

Michael Watts said,

September 28, 2023 @ 10:52 pm

I see that I forgot to provide a closing </blockquote> tag. Only the first sentence currently getting blockquote treatment should be blockquoted. :(

Peter Grubtal said,

September 29, 2023 @ 3:43 am

ktschwarz , Michael Watts

Thanks for information to my question. I guess I should have searched further myself, but I didn't imagine that Wikipedia for example would go into such detail.

Philip Anderson said,

September 30, 2023 @ 3:13 pm

@Jonathan Smith

I think that is explicit in the preceding sentences:

“The most enduring aspect of a language is its structure, which can persist over millennia. My studies indicate that the Great Andamanese were effectively isolated for thousands of years, during which time their languages evolved without discernible influence from other cultures.”

She accepts that the language evolves, but not so much that the “structure” could change, not without external influence. Languages can certainly change under the influence of other languages, but is that the only trigger for a major change in “structure”, whatever that means?

Languages do undergo big grammatical changes during their history, and I don’t think we can always blame language contact – loss of grammatical endings, new tenses, initial mutations …

Jonathan Smith said,

October 1, 2023 @ 9:46 am

@Philip Anderson

Perhaps rather than implicit/explicit the claims are simply a bit vague.

Yes hard to find parallels for change in a vacuum. But e.g. Eastern Polynesian is supposed to be relatively uniform… and even there mutual non-intelligibility means that individual languages have changed in substantial ways sans contact in on the order of 1000 yrs… let alone 50 times that.

Sean Lu said,

October 7, 2023 @ 10:09 pm

I can't help but be reminded of this SpecGram article https://specgram.com/CLI.b/02.tirizdi.corpses.html upon reading "Grammar Based Entirely on the Human Body"