The importance of stress in Chinese utterances

« previous post | next post »

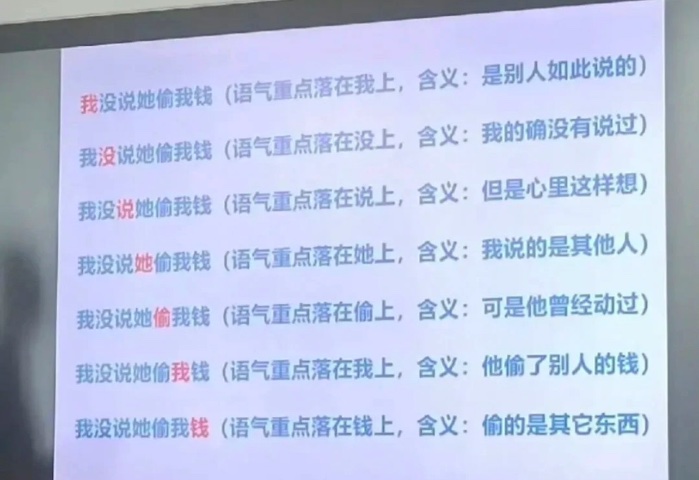

Photograph of a slide shown in a classroom in China:

The slide shows a single sentence of seven morphosyllables spoken in seven different ways according to what the speaker wishes to emphasize. Here's the basic sentence without any particular emphasis:

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

"I didn't say that she stole my money".

Now, going through the seven variants one at a time, starting by stressing the first syllable and then, proceeding through the whole series of seven example sentences, putting the stress on the next successive syllable:

1.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

It wasn't I who said that she stole my money. (somebody else said it)

2.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I've never said that she stole my money. (I indeed never said such a thing)

3.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I never said that she stole my money. (though I may have thought that she did)

4.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I never said that she stole my money. (rather that someone else did)

5.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I never said that she stole my money. (rather that she messed with it)

6.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I never said that she stole my money. (implying that she stole someone else's money)

7.

Wǒ méi shuō tā tōu wǒ qián.

我沒說她偷我錢。

I never said that she stole my money. (implying that she stole something else of mine)

This is another installment in the long-running debate over the importance of non-tonal features in Sinitic utterances. (See under "Selected readings".)

To be continued, the next chapter being drawn from a Classical Chinese text.

Selected readings

- "When intonation overrides tone, part 6" (5/9/21) — with a long, cumulative list of relevant posts

- "Mair's hypothesis on tonal repetition" (7/6/21)

- There are numerous other posts on tones, stress, emphasis, accent, and suprasegmental phonological phenomena.

P.S.: I just heard an M.A. student from China, as he was getting on an elevator, say: Wǒ méi bànfǎer 我没办法儿 ("I can't / I had no way out / I had no choice [but] / I was unable to find a way out / I couldn't help [but]"), but it came out as "ǒ méi bã̀er", with slight nasalization on the "a" and dwindling off, dropping of the pitch of the "-er" portion, another example of slurring and suprasegmental features that we have often discussed on Language Log.

[Thanks to Qingchen Li]

cameron said,

October 13, 2022 @ 11:59 am

is there such a thing as a language where speakers can't shift emphasis within a sentence by stressing certain words or syllables?

Philip Anderson said,

October 13, 2022 @ 2:03 pm

Don’t you get exactly the same nuances from shifting the word stress in the English “I never said she stole my money”?

Bob Ladd said,

October 13, 2022 @ 2:06 pm

@ Cameron: Possibly. In any case the extent to which speakers can do this varies a lot from language to language, with various grammatical restrictions, etc. English and the Germanic languages are enthusiastic emphasis-shifters compared to many languages.

There's a paper in Phonology by Gussenhoven and Maskikit-Essed reporting on a variety of Malay in which (they say) speakers really cannot (or do not) shift emphasis around, and various other evidence seems to confirm their interpretation.

David Marjanović said,

October 13, 2022 @ 3:19 pm

Yes – and that's very interesting for two reasons:

– it means stress exists in Mandarin, in addition to the tones;

– it's more or less the same thing as contrastive stress, which is, in Europe at least, a peculiarity of the Germanic languages. In mi casa es tu casa, you stress casa, not mi or tu, and in de neuf heures à treize heures, you stress heures. Focus particles are a widespread alternative (e.g. Slavic languages put /ʒɛ/ after the word that is to be emphasized).

Philip Taylor said,

October 13, 2022 @ 4:22 pm

I think that it might be very helpful, Victor, if you (or a native speaker in your department) were to record those seven utterances and upload them to this web site so that others can hear at first hand how stress interacts with tone in MSM.

Chris Button said,

October 13, 2022 @ 6:53 pm

@ David M

Contrastive focus aside, isn’t that to do with the fact that in Spanish it doesn’t sound strange to put intonational focus on the same word across two connected intonational phrases, whereas in English that sounds awkward for some reason.

Jonathan Smith said,

October 13, 2022 @ 7:12 pm

Whether/how Chinese(-type tonal languages) could employ "intonation" was a subject of debate 100-ish years ago… the/a formative discussion is Y.R. Chao 1933, Tone and intonation in Chinese. His famous ripples-on-waves metaphor, in which intonation is seen to modulate tone (or vice-versa?) (cf. MYL's comment on When intonation overrides tone, part 3, is later… the internets suggest 1968.

To me the special-est (unresolved?) situation involves "sandhi"-heavy systems like Southern Min languages, in which the "sandhi" variant of Tone X may be (considered to be) the same as the "citation" variant of Tone Y (e.g. Taiwanese "sandhi" 3 = "citation" 2, etc.) and yet the native intuition remains that the citation tones per se across the board register (perhaps among other things) emphasis — so can this "emphasis" be detected in terms of phonetic correlates unrelated to tone (like duration/volume…), in which case the native intuition is partly illusory or weirdly outdated? or what

Phil H said,

October 13, 2022 @ 7:34 pm

I'd love to see an analysis of exactly what the features of sentence stress are in Mandarin. I'm a native speaker of BrEng, and fluent in Chinese, but I still have a foreign accent. One of the things that makes my Chinese sound a bit non-native is that I still use too much stress variation in my sentences. In general, Chinese has smoother stress contours than English.

In particular, I think that Chinese sentence stress makes more use of pause and exaggeration of the tone than English does. That particular sentence is in all the primary school textbooks, so I've tried reading it before, and it feels like the way you "do" stress in Chinese is to pause before the stressed syllable and exaggerate its tone (as well as making it louder and higher pitched). But I don't know if this is really what's going on.

Jerry Packard said,

October 13, 2022 @ 8:14 pm

Phil H. – Sounds like you've got it figured out pretty well. For Mandarin sentence stress the investigators you'd want to take a look at are Susan Xiaonan Shen and Chilin Shih.

Scott Mauldin said,

October 14, 2022 @ 12:30 am

I've seen this exact same sentence, in English, some ten years ago on Wikipedia demonstrating stress in English.

David Marjanović said,

October 14, 2022 @ 7:45 am

That's what contrastive stress is. Spanish lacks it, English has it.

Jenny Chu said,

October 14, 2022 @ 9:03 am

In some Slavic languages, word order can be used for this purpose. Because the overt morphological declinations & conjugations obviate the need for strict word order, you can play around with the word order to achieve emphasis. Like "I love her" (neutral) vs "Her I love" (I love her [not him]).

Chris Button said,

October 14, 2022 @ 9:28 am

@ David M

Spanish uses changes in word order for contrastive focus where English would use contrastive intonational focus, but i don't believe it to be true that Spanish does not use contrastive intonational focus. Why do you believe that to be the case?

Bob Ladd said,

October 14, 2022 @ 12:19 pm

@Chris Button: It may be true that in almost any language can put some kind of "stress" on an individual word for broadly "emphatic" purposes. But what David M is talking about is the tendency to move sentence level stress around for essentially negative reasons, i.e. in order to deaccent words that would otherwise be accented, as in his example mi casa es tu casa. In English it would be normal to say MY house is YOUR house, whereas in Spanish it would be normal to say mi CASA es tu CASA. The English pattern is often called "contrastive stress", but it's at least as much a matter of NOT accenting house rather than contrasting my and your.

Marc Swerts and colleagues have done various experiments where two people have to alternately draw cards and name the simple coloured shape shown on the card (e.g. red circle, blue triangle. If there are two consecutive occurrences of the same shape, Dutch and English speakers almost always shift the stress (e.g. A: blue triangle; B: RED triangle). In comparable circumstances given two consecutive occurrences of the same colour, Italian and Romanian speakers almost never do this (e.g. A: triangolo blu; B: quadrato blu [i.e. not QUADRATO blu]).

Chris Button said,

October 14, 2022 @ 12:58 pm

@ Bob Ladd

Your triangle example is exactly my point. I'm not sure why any new experiments were needed though. It goes at least as far back in English works as Roger Kingdon's intonation book from the 1950s.

And yes, i agree that "contrastive stress" is the wrong term here. In my layman opinion, it's not being done for contrastive reasons and I personally would avoid using the term "stress" in these contexts.

Bob Ladd said,

October 14, 2022 @ 1:15 pm

@Chris Button: We can at least agree that the term "stress" is part of the problem. Unpacking "stress", "focus", "emphasis", "contrast" and more reveals just how complicated these issues are. And to go back to the OP, the idea that "tone" and "stress" are somehow incompatible is what makes the Chinese example seems like a problem.

Chris Button said,

October 14, 2022 @ 1:15 pm

And so, again speaking not as an expert in these matters, it seems only to be tangentially relevant to the topic under discussion.

Victor Mair said,

October 14, 2022 @ 1:18 pm

Thanks to all for the productive, informative conversation.

Chris Button said,

October 14, 2022 @ 1:20 pm

@ Bob Ladd

Sorry, that was a follow up to my previous comment, not as a response to the your last one .

Yes it's all a little messy in terms of terminology!

Victor Mair said,

October 15, 2022 @ 10:37 am

I am especially grateful to those who asked about how stress and tone are articulated / combined in actuality, since the scholarly / theoretical literature does not give an adequate / apprehensible explanation of how the two are simultaneously expressed in a given utterance, which is the main point of this post. My own description of how it works out in practice, based on observations of countless native speakers, is roughly as follows.

The morphosyllable being emphasized is:

1. spoken with greater volume

2. is slightly raised (1, 2, 4) or lowered (3), depending upon its original tonal contour / quality

3. is lengthened / extended upon delivery

All of these feature conspicuously call attention to the syllable being stressed without eliminating the original tone, but rather accentuating it.

Philip Taylor said,

October 15, 2022 @ 11:37 am

Excellent, thank you Victor — your prose description makes an audio recording almost unnecessary. although it would still be interesting to hear the seven sentences spoken …

Michael Watts said,

October 20, 2022 @ 12:59 am

It's worth noting that this is a standard example in the English-language literature; one of Steven Pinker's works provides an example of such focal stress in a sentence, and the sentence is "I didn't say he took the money".

Technically, this means that the pictures above might represent a real phenomenon in Mandarin, or they might represent someone reading about the English phenomenon and assuming it applies to Mandarin too.

Given that this is just one picture of a slide, it might also represent a discussion of how English works, with the English sentence rendered in Chinese for whatever reason.

The larger phenomenon of a particular cultural reference appearing elsewhere uncredited can be interesting. I took a class in Chinese at a Chinese university, and the writing teacher once told us to start something off the prompt 天黑了,外面下着雨. (Literally "the sky [was] black, [and it was] raining outside".)

I immediately recognized this as a Chinese translation of the reasonably-well-known English cliche "it was a dark and stormy night". No one else in the class recognized the sentence, or understood why it would prompt me to draw a picture of Snoopy.

Sanchuan said,

October 29, 2022 @ 5:05 pm

I second Michael Watts here. Sure, any language can exhibit some degree of free sentence stress for strictly emphatic purposes and, sure, isolating languages like Chinese can do that pretty easily, as kindly described by Prof Mair in the comments above.

But the one in the OP is a very specific exercise that's used to show how contrastive and/or noncontrastive sentence stress is a pretty much grammaticalised feature of English – because you can hardly utter a sentence without it, whatever the register. However, it is not a feature that's at all obvious in standard Mandarin and definitive research on the matter is still in its infancy. If anything, I would say that the communicative intent behind most of those English stress patterns are far more naturally resolved in Chinese by means of topicalisations or the apt use of a 就 or a 才 and other such function words.

So it's hard to think that this *isn't* a case of intercultural, and potentially interlinguistic, transfer, where an academic meme (if only a meme in English Prosody 101!) is regurgitated abroad by ambitious teachers often over-schooled in English language material to start with. This is also the sort of material that's easily misconstrued as a universal fact of language or as a prescriptive rule of 'developed' Western languages – and potentially taught just as prescriptively in spite of native instincts or actual reality. We've seen this happen already with official language material from the PRC now starting to talk of obligatory 'subjects' and other such English-centric rules and shibboleths.

But, hey, why research your own prosody if you can just import someone else's, right? It rather reminds one of how English, too, as an up-and-coming language, used to adopt Latin rules to legitimise itself. Who knows, maybe a few generations hence being a conservative Chinese speaker will mean being a stickler for obligatory pronouns, English-like intonation and other such 'rules'!