Chris Waigl helps fire managers

« previous post | next post »

Chris Waigl is a longtime friend of Language Log — among her many accomplishments is the creation of the Eggcorn Database in 2005 (with contributions from Arnold Zwicky and me). These days she conducts post-doctoral research in the Boreal Fires team of the Alaska EPSCoR Fire and Ice project at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and she also teaches in the UAF College of Natural Science and Mathematics. Recently on Facebook, Chris shared an article from the Anchorage NBC affiliate, KTUU Channel 2, about the team she works with at UAF. The headline for the article is striking: "Alaskan-developed satellite technology helps fire managers in COVID-19 era."

As Vadim Temkin asked Chris on Facebook, "Why are you firing poor managers?"

Yes, it's a crash blossom, a headline with enough ambiguity to suggest a wildly different interpretation. In this case, the technology that Chris and her team have developed is not helping to fire those poor managers, who are just trying to get by in the COVID-19 era. Instead, the team is helping "fire managers" — people who work in wildfire management. As the article explains:

COVID-19 is impacting the way land managers prepare for and respond to wildfires, but satellite technology developed at the University of Alaska Fairbanks is helping provide data to help managers make informed decisions.

This is reminiscent of one of the classic crash blossoms, "Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim." It's such a classic that it served as the title of an anthology of humorously ambiguous headlines published by the Columbia Journalism Review in 1980, long before "crash blossoms" first got their name in 2009.

Since the misreading here relies on interpreting "X helps NOUN NOUN" as "X helps VERB NOUN" (with fire changing part of speech), it's structurally similar to a crash blossom that Mark Liberman shared in a 2017 post, "Queen Mother tried to help abuse girl." That item in the (UK) Times illustrates the tendency of British headline writers to string together nouns into longer noun phrases (sometimes resulting in unwieldy noun piles). "Abuse girl" here referred to a girl who suffered abuse. (Online, at least, the Times revised the headline to read, "Queen Mother tried to help abused girl.")

As Chris Waigl noted on Facebook, "when you're not used to the N-N compound, you might more easily get garden pathed" by the "X helps NOUN NOUN" construction. She added, "To me, 'fire managers' is such a set phrase that it takes effort to wrench it apart, but to someone who isn't steeped in this terminology it would not be." This is one of those situations where hyphenating compounds would dispel confusion: if the headline referred to "fire-managers," we'd all be able to join Chris in recognizing it as a set phrase.

Andrew Usher said,

June 15, 2020 @ 5:49 am

I suppose 'firing poor managers' is another double meaning, this time intentional. That ambiguity is not a different part of speech, but is still basically so.

Will anyone ever bring back the eggcorn database, or a replacement for it – or has someone already? I used to check it for updates frequently, and of course didn't really care who was running it.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com

Philip Taylor said,

June 15, 2020 @ 6:23 am

Not an egg-corn, not a crash blossom, but can anyone (presumably a native speaker of <Am.E>) please explain the following, copied without error from the npr.org web site ?

Are "jail" and "prison" really different in <Am.E>, or am I simply missing the point ?

I was further confused by the use of "recall" — I initially thought that the judge in question was being "recalled" from retirement (or whatever) in order to once again serve on the bench. On reading further, however, it would seem that in this case he was being "recalled" in order to prevent him from serving on the bench. We are indeed, two nations divided by a common language.

Andrew Usher said,

June 15, 2020 @ 6:35 am

Yes, 'jail' and 'prison' are legally different here; which one you get sent to normally depends on the length of your sentence. 'Jail' (and I think British agrees here) is also where people are held before trial – and speaking of spelling changes over your lifetime, isn't 'jail' replacing 'gaol' one of them?

I am not able to comment on the remainder of this without getting political.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo dot com

Philip Taylor said,

June 15, 2020 @ 6:49 am

Well, thank you for that, Andrew — I learn something new here every day. According to the OED :

So originally just as you say, but now (in British English, at least) the meanings have merged. And yes, "gaol" -> "jail" is indeed yet another change in British English orthography that has taken place in my life-time. It took me many years (as a child) to discover that "gaol" is not pronounced /ɡəʊl/.

John Swindle said,

June 15, 2020 @ 7:23 am

Another distinction between jails and prisons in the US is that jails are operated by city or county authorities, whereas prisons are under state or federal authority. Doesn't Britain have the local lockup?

Recall is a process in some US jurisdictions whereby citizens can remove an elected official from public office before their term of office ends. Citizens petition for a special election to decide on the removal. Recall is not available in every state or applicable to every position. It would not, for example, be applicable to what's-his-name.

In American English you can talk about recalling someone to military service, so I don't think it would be wrong to talk about recalling someone to office, but it might be confusing because

John Swindle said,

June 15, 2020 @ 7:24 am

Sorry. "… but it might be confusing because of the existence of the other meaning."

David Morris said,

June 15, 2020 @ 7:30 am

In Australia jail/gaol and prison are interchangeable in ordinary use. If there is a legal distinction, I can't immediately think of it. Most of the sites I can immediately find say 'sentenced to imprisonment'. There must be some which say 'sent to ____'.

Courtesy of a tired brain not controlling my fingers, I have just realised that jailers/gaolers and prisoners are very different people.

David Morris said,

June 15, 2020 @ 7:31 am

PS The place some people are held before trial is a remand centre.

Philip Taylor said,

June 15, 2020 @ 8:00 am

John, no, the "local lock-up" disappeared many years ago, probably before I was born. Someone arrested is initially detained in a police station, then (if commited for trial) to a remand centre, and so on. As in Australia, "jail/gaol" and "prison" are now synonyms in the U.K.

Andrew M said,

June 15, 2020 @ 8:45 am

My sense is that 'jail' is mostly used in headlines, as being shorter; 'prison' is the word that most people would normally say.

Philip Taylor said,

June 15, 2020 @ 9:10 am

Certainly as a verb, "jailed" would be preferred over "imprisoned", whether in headlinese or otherwise. "Imprisoned" carried connotations of "extra-legal" or "unintentional" imprisonment", whereas "jailed" is (in my experience) reserved solely for legal imprisonment. But, living near Bodmin (Cornwall, south-west England) as I do, "Bodmin Jail" is a phrase that one hears almost every day.

Robert Coren said,

June 15, 2020 @ 9:47 am

@Andrew Usher: Re "firing poor managers", it might be a useful data point that Vadim grew up in Russia, and I know (from being personally acquainted with him) that his English is fluent but fairly heavily accented, and he still has a tendency (common among Russian-speakers) to omit articles in English. A native speaker would have said "Why are you firing the poor managers?" (or perhaps "those poor managers"), which would have reduced (but not eliminated) the ambiguity.

Gregory P Kusnick said,

June 15, 2020 @ 2:24 pm

"Helps land managers" wouldn't be much better; it still invites the interpretation that satellite technology is being used as an HR tool (recruiting rather than dismissal in this case).

To me, "jail" connotes a lower level of security than "prison". My town has both: a county jail right downtown behind the courthouse, and a state-operated prison about ten miles out of town, complete with razor wire, guard towers, dog patrols, and so on. Jail is for short-timers; prison is for serious offenders serving lengthy sentences.

Alexander Browne said,

June 15, 2020 @ 2:37 pm

I agree with the impressions of the American (and Canadian?) difference between jail and prison, but want to add that "jail" is also colloquially used to mean "prison", both casually and in print, then especially in phrases like "jail time".

For example, from Newsweek a couple weeks ago: "police officers rarely face jail time even in cases of severe legal misconduct." (https://www.newsweek.com/protesters-want-first-degree-murder-charge-against-derek-chauvin-that-might-acquit-not-convict-1508785)

Andrew Usher said,

June 15, 2020 @ 6:17 pm

Indeed, 'jail' is used that way, perhaps because 'to jail' is a verb and 'to prison' is not, it's a bit shorter, and common usage doesn't really need the difference between the two.

People held at the police station are also colloquially said to be 'in jail'; I don't think America has the term 'remand center' at all, even as jargon, though 'remand' does exist.

Daniel Barkalow said,

June 15, 2020 @ 11:31 pm

I can't avoid thinking: "I say we fire them all from orbit. It's the only way to be sure."

Howard said,

June 16, 2020 @ 7:02 pm

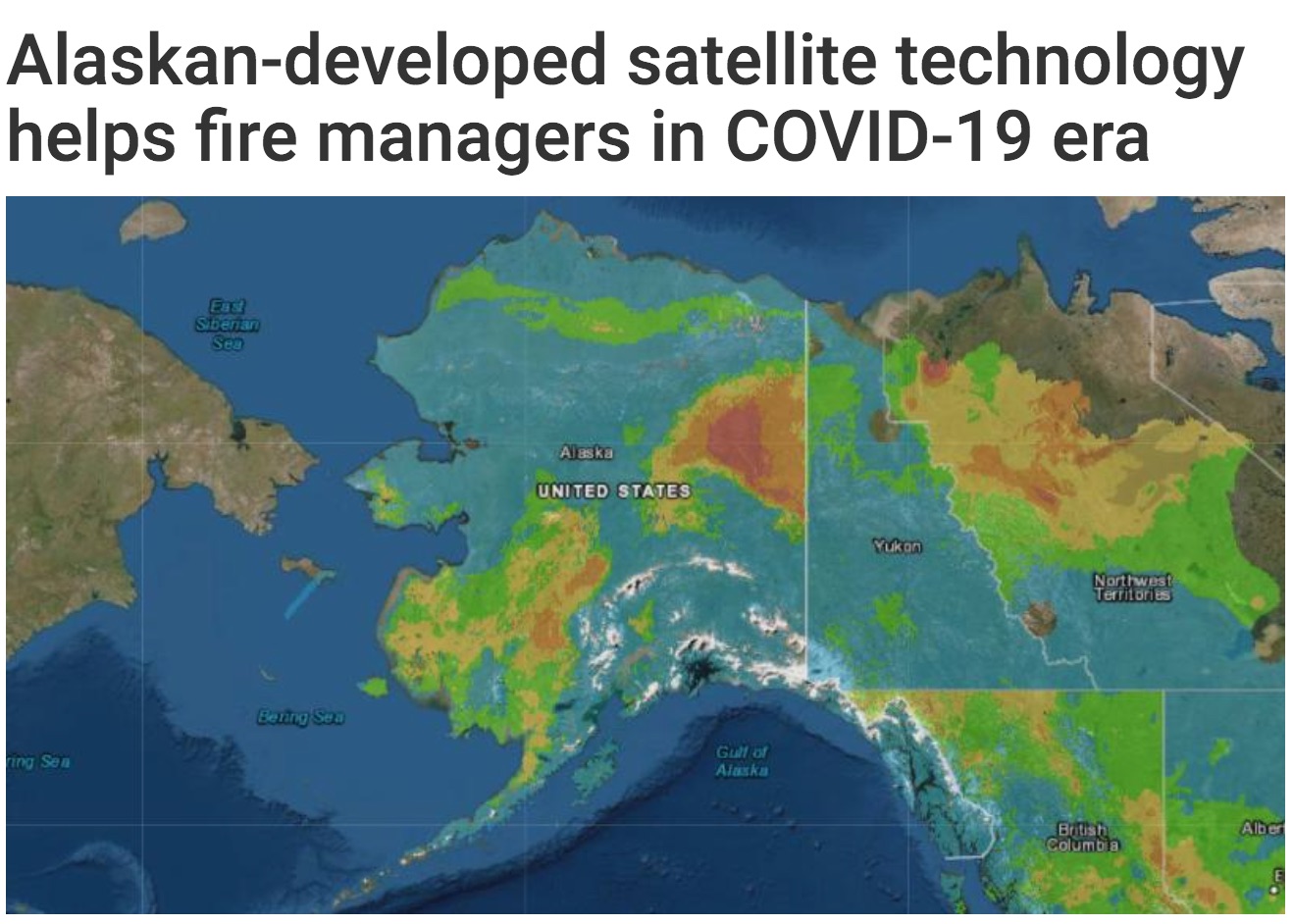

The N-N versus V-N confusion is not the only thing being communicated here. The image is saying that something stops abruptly at otherwise arbitrary borders. What is different about Yukon? Is it lack of data or different practice? Is the map just a filler, like, um, you know what I mean? To me, that is a much greater instance of ambiguity. Good cartography = meaningful communication.

Andrew Usher said,

June 16, 2020 @ 7:52 pm

I don't think the map intended any such things: it was merely compiled from data that's obviously not all on the same scale. The fact that Alaska differs from Yukon, and the Canadian provinces indeed from each other, is unfortunate but not within his power to correct, nor could the article writer do any better.

Robert Coren: (on the ambiguity of 'poor managers')

Thanks, understood. The usage of articles in English is notoriously difficult. I can't come up with any explanation right now, other than pure arbitrariness, for the fact that the 'pitiful' sense would normally take an article and the 'underperforming' sense normally would not.

Rodger C said,

June 20, 2020 @ 9:06 am

I think that in "the poor managers," "poor" is sort of a quasi-expletive word inserted into "the managers." "Poor managers" are "managers that are poor." "The poor managers" are "the managers, bless their hearts."

Philip Taylor said,

June 20, 2020 @ 1:40 pm

I go along with Rodger here — "poor f*****g s@ds" is a pretty common expletive phrase (in the U.K.) to describe a group of people for whom you feel great pity.