Katakana nightmare

« previous post | next post »

Bob Sanders writes from Kanazawa, Japan:

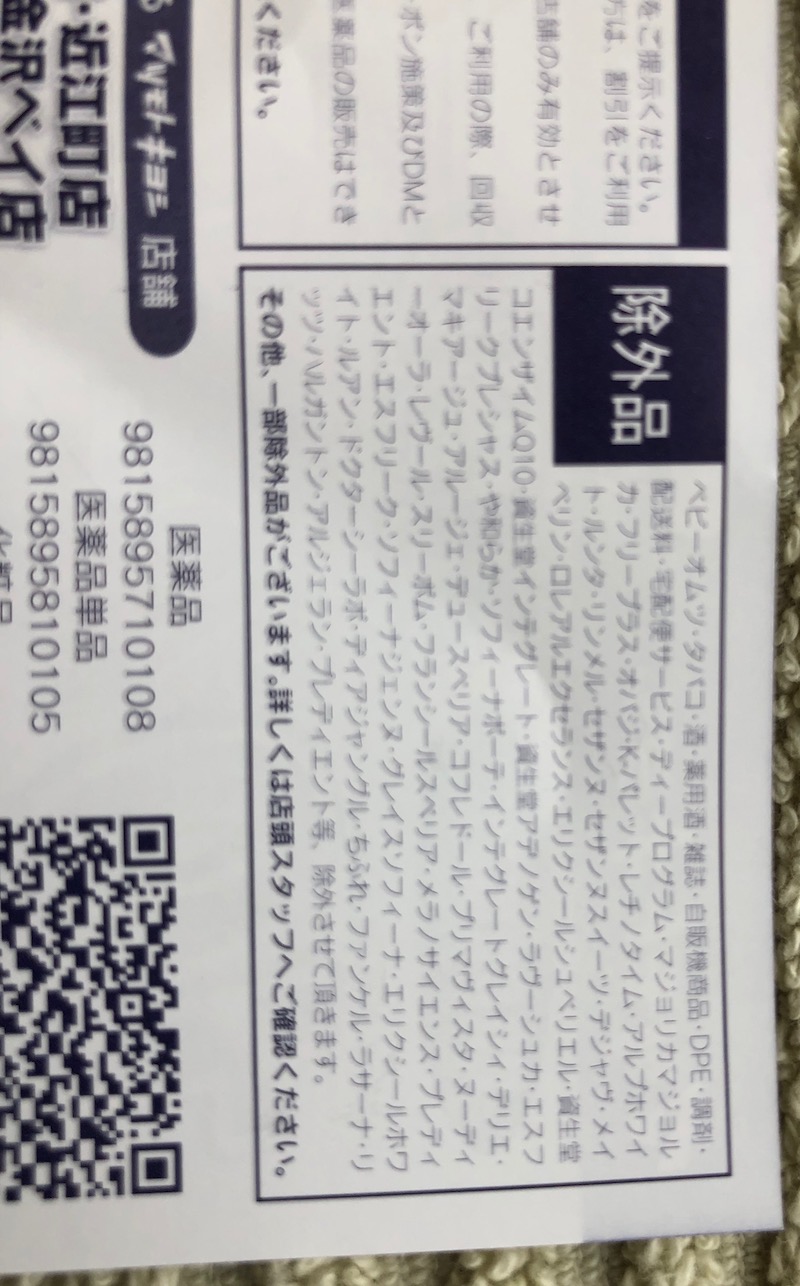

Today I bought some mouthwash at a national pharmacy chain and received a coupon for a discount on any two future purchases made later this month, with certain items excluded from this offer. In fact, it is this list of exclusions which immediately caught my attention (see photo below), because it so graphically highlights why for me, at least, as someone who came to Japanese much later in life with a background in Chinese language studies, katakana, rather than kanji or hiragana, is the most difficult of the three orthographies to process orally in my brain.

Very short strings of katakana are not much of a problem for me, but as a string gets longer, it gets increasingly difficult to keep going, and eventually my brain gets tied up in knots and shuts down. I believe that the reason for why this is so relates to the amount of graphic redundancy that is built into each grapheme. Whereas any randomly selected pair of kanji or hiragana are likely to differ from one another graphically in a large number of ways, katakana have much fewer cues to distinguish one grapheme from another.

Readings

"More katakana, fewer kanji " (4/4/16)

"Kanji as commodity " (4/30/18)

"The economics of Chinese character usage " (9/2/11)

Andy Averill said,

June 20, 2019 @ 4:14 pm

I usually silly mnemonics

シ SHI is really happy today

オ O I really enjoy figure skating

ト Does my TO look all right to you?

Andy Averill said,

June 20, 2019 @ 4:18 pm

I usually USE silly mnemonics. Works for hiragana and (some) kanji too.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

June 20, 2019 @ 4:58 pm

Apart form the lack of spaces between the words, just like in Pinyin, the font can hinder word segmentation and even syllabary segmentation, unlike Romaji: for example Hiragana Wa & Re, or Katakana Ro vs Ru.

Alyssa said,

June 20, 2019 @ 5:00 pm

I always attributed the difficulty of reading long katakana strings to the effort of "sounding it out", where I'm simultaneously trying to hold all the sounds in my head while applying them to my english vocabulary. But I think Bob Sanders might be right about the graphemes causing problems as well – katakana really are visually homogeneous in a way, sort of like cursive handwriting can be in English.

J.W. Brewer said,

June 20, 2019 @ 5:06 pm

I'd always understood/assumed that the reason katakana is often used in advertising-type situations was that it was "easier" to decode/process in that sort of quick visual scan context than kanji or hiragana. But I guess whatever features that might make it preferable for a short label/slogan/etc are not inherently inconsistent with it being more difficult to follow in long blocks of running text?

Would more spacing between words help? I wonder if the comparative infrequency of long all-kana chunks of running text has hampered the evolution of approaches to typography and layout that would maximize ease of reading.

J.W. Brewer said,

June 20, 2019 @ 5:12 pm

A partial parallel to the puzzle I suggested in the prior comment might be that in English (and I assume other Latin-scripted languages) it is common to use ALLCAPS for contexts like signage where the message is comparatively short but not to use ALLCAPS for longer pieces of running text – probably in part because it somehow enhances ease of reading in the former context but degrades it in the latter.

Bathrobe said,

June 20, 2019 @ 8:31 pm

The fact that the photo is fuzzy doesn't help, but reading the katakana isn't a big problem. For me the main problem is identifying the words. If they were identifiable English (or even Japanese) words it would be easy. So bebii omutsu 'baby's nappies' is clear enough. But I have no idea what dyūsperia or kofuredōru are (just to pick two random words), and I would have great difficulty stumbling through that jungle of katakana. I would have similar problems reading the ingredients of Chinese medicine written entirely in Chinese characters.

unekdoud said,

June 21, 2019 @ 12:54 am

I don't use mnemonics for kana except for the pretty amusing resemblance of ん and n, but it took a lot of practice/exposure to stop confusing them. The worst pair for me was ン (katakana n) and ソ (hiragana so), distinguishable almost only by context.

The list in the picture is labeled "excluded products", and many of the items on it appear to be brand names. So while I could sound out コフレドール (kofuredōru from Bathrobe's comment) and recognize it as "coffret doll", I still have no idea what kind of product it is.

Jim Breen said,

June 21, 2019 @ 1:57 am

Long strings of katakana are often a challenge, even to native speakers of Japanese. The key thing is to work out the component parts, which are often quite ambiguous.

A few years back I developed an automated segmentation/translation approach which seems to work quite well. It runs on a server at http://nlp.cis.unimelb.edu.au/jwb/clst/gairaigo.html and is described in a conference paper: http://www.edrdg.org/~jwb/paperdir/extgaimwe.pdf

コフレドール is "coffret d'or", a product line from Kanebo Cosmetics Inc.

Philip Spaelti said,

June 21, 2019 @ 3:43 am

I think the problem here is with reading fluency. Reading fluency depends strongly on familiarity, but the way Katakana is used in Japanese fundamentally results in a bias against familiarity. Except for a very few common items (コーヒー) Katakana is used for unfamiliar/infrequent words which means that when the reader encounters a string of Katakana they will resort to "sounding out", which I take it is what the original poster means by "process orally in my brain". Phonic reading is uncomfortable for fluent readers.

The lack of graphic distinction in the Katakana is caused by the fact that the fonts used try to assimilate the characters to the graphic image created by the Kanji. Early 20th century attempts to make an all Katakana script (using word breaks of course) give the kana a much more distinctive appearance. Toyota uses a very striking Katakana representation of their brand name in Japan.

R. Fenwick said,

June 21, 2019 @ 4:51 am

@Alyssa:

But I think Bob Sanders might be right about the graphemes causing problems as well – katakana really are visually homogeneous in a way, sort of like cursive handwriting can be in English.

For similar reasons I'm a little baffled that Armenian has maintained the older glyph style that Georgian abandoned when it moved away from the use of the reed-pen-influenced Nuskhuri. I've always found the Armenian alphabet, particularly in manuscript forms, to have such extraordinary homogeneity in glyph forms that I genuinely wonder sometimes how Armenian dyslexics fare.

A Caucasologist colleague of mine dislikes Cyrillic for a similar reason; though the character forms are a little more varied than one sees in Armenian, he finds the lack of variation in character heights to be visually confusing (ф б ц щ being the only minuscule Cyrillic characters with either ascenders or descenders, and the descenders on the last two are very small in any case), and consequently it's somewhat hard to scan a page and look for particular words by shape alone.

Brett Reynolds said,

June 21, 2019 @ 5:48 am

Keiko Koda has demonstrated quite conincingly that any difficulty reading katakana is mere a familiarity effect. Expert readers of Japanese process katakana verions of words more slowly only when they are not typically written in katakana, and conversely, words typically written in katakana are processed more slowly in hiragana. People can learn to read fluently in katakana. As with most things, it's a matter of practice.

Keith said,

June 21, 2019 @ 8:42 am

@R. Fenwick

I find your comment about Armenian and Cyrillic very interesting.

I managed to learn the Cyrillic alphabets (first of all Yugoslavian and later Russian and Ukranian) really easily; it would be no exaggeration say that it took me no more that about a week to decipher Yugoslavian Cyrillic (at the age of 12) from limited samples taken from coins and stamps. Later, starting ab-initio Russian at university, I was reading Russian out loud from printed texts after a week of class, while classmates were still transcribing into Latin letters well into the second semester.

I put this down to the similarity with Greek that I'd been exposed to in maths and physics classes long before starting to get interested in Slavic languages.

But each time I've tried to get started learning Armenian, I've really struggled with the alphabet.

cliff arroyo said,

June 21, 2019 @ 1:17 pm

I learned the (printed) letters of cyrillic very easily but once past the decode-every-letter stage I found it hard to read than the greek alphabet.

Past a certain point I wasn't able to identify words by overall shape fast enough (again never a problem with greek). I'm assuming (like most people) that it's the relative lack of ascenders and descenders… I have a similar problem with all caps Greek (my decoding speed slows to a painful crawl).

I'm assuming for native speakers of cyrillic using languages the overall context helps compensate for the general… blockiness of the script but for non-natives I think it's a real factor that makes reading fluently (and not mostly deciphering individual words) harder.

Vanya said,

June 22, 2019 @ 12:58 am

classmates were still transcribing into Latin letters well into the second semester.

Seriously? I find that shocking. I learned Cyrillic from a textbook in a day. Same with Greek. It’s not so different from having to map different and weird sound correspondences onto Latin letters if you learn Dutch or Turkish, and in many ways easier.

Hebrew, on the other hand, I find very difficult to interalize.

Annette Pickles said,

June 22, 2019 @ 5:00 am

This post reminded me of this incident:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/06/27/national/gifu-man-71-sues-nhk-for-distress-over-its-excess-use-of-foreign-words/#.XQ37WetKipZ

I believe the court eventually dismissed his case.

Chris Button said,

June 22, 2019 @ 6:53 am

@ Brett Reynolds

Presumably that refers to familiarity with the words represented rather than the actual script itself.

@ J. W. Brewer

As a very crude approximation, I would think that reading something in pure hiragana or katakana is somewhat akin to reading something in all caps in English. A combination of kana with with kanji would be more like using upper and lower case in English.

Chris Button said,

June 22, 2019 @ 7:02 am

By the way, isn't interesting that hiragana undergoes "rendaku" (i.e. voicing of the /k/ in kana to /g/) while katakana doesn't?

Chris Button said,

June 22, 2019 @ 7:09 am

I wonder if the exception in this case has anything to do with the lack of voicing on both consonants in kata combined with voicing being phonetically harder to maintain on /k/ than /p/ or /t/ for example (since we do have things like "tokidoki" after all)?

Jim Breen said,

June 22, 2019 @ 7:16 pm

@Chris Button

The rendaku process is a feature of spoken Japanese and really has nothing to do with the script. The restriction of katakana to (mostly) loanwords, which of course do not undergo rendaku changes, was part of the 1940s script reforms. Before that one did encounter native Japanese words in katakana, complete with the voicing features of rendaku.

Jonathan Smith said,

June 22, 2019 @ 8:19 pm

@Jim Breen I believe Chris Button is wondering why rendaku applies in the word hiragana but not in the word katakana. No clue here…

PeterL said,

June 22, 2019 @ 9:23 pm

Japanese telegrams used to be in all katakana.

Some years ago, a friend who worked at Itōchū told me that internal memos were in all katakana (no idea if that's still the case). Presumably they wouldn't have done this if katakana decreased readability significantly. (I don't know the details, e.g., did they add spaces the way Japanese children's books in all-hiragana do?)

Here's an example with kanji glosses mostly in katakana: https://www.picomico.com/p/1996443285662262120_5725057975

Syllabaries seem to be easier to learn than alphabets — at least, my children, who had both Japanese and English stores read to them, learned hiragana on their own before they figured out how to read English.

As to rendaku (why "hiragana" and not "katakana") — here's one explanation: https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/rendaku/

Chris Button said,

June 22, 2019 @ 10:13 pm

@ PeterL

Thanks! So at least, there is consistency with the example cited there of 片 (かた) + 方 (ほう) = 片方 (かたほう)