Pop platonism and unrepresentative samples

« previous post | next post »

A few days ago, Arnold Zwicky expressed some annoyance at the New Scientist's cover story of July 19 ("Sex on the Brain", 7/22/2008). Arnold couldn't stand "to reflect on yet another chapter in this story", and I'm not especially enthusiastic about this either, especially because as far as I can tell, the New Scientist's story lacks any news hook. But this case raises a couple of points about the rhetoric of science journalism (and sexual science) that are worth making yet again, even though they've been made many times before.

A few days ago, Arnold Zwicky expressed some annoyance at the New Scientist's cover story of July 19 ("Sex on the Brain", 7/22/2008). Arnold couldn't stand "to reflect on yet another chapter in this story", and I'm not especially enthusiastic about this either, especially because as far as I can tell, the New Scientist's story lacks any news hook. But this case raises a couple of points about the rhetoric of science journalism (and sexual science) that are worth making yet again, even though they've been made many times before.

Hannah Hoag's story appears under a headline that's really strange, if you think about it for a minute: "Brains apart: The real difference between the sexes". The implication is that all that stuff about genitals and the uterus, breasts and facial hair and larynx and so on, are fake or at least superficial differences — the "real difference" is in the brain. Furthermore, if the neurological differences are so much realer than all those differences in other body parts, then male and female brains must be really different, right?

But in fact, the various neurological differences that Hoag goes on to cite generally emerge from studies of small numbers of student subjects, which find average differences between males and females that are small compared to variation among males or among females — in contrast to the essentially categorical differences in primary sexual characteristics (like genitals) and the nearly categorical differences in secondary sexual characteristics (like facial hair and voice pitch).

Despite this, Hoag's discussion is all about generic-plural "men" and generic-plural "women" — or about "the men" and "the women" in a given study — as if she was telling us things that are true of essentially all men and essentially all women, or at least all the men and women tested. As I've often observed before, this pop-platonism is a kind of linguistic and conceptual trap that most science journalists — and many scientists — seem to be unable to escape from ("The Pirahã and us", 10/6/2007).

And Hoag's article also demonstrates the peculiar and equally-characteristic willingness to generalize from small numbers of student subjects to the human species at large, in a way that would be viewed as pathetically naive if we were talking about voters' reactions to politicians or consumers' reactions to brands of toothpaste. This is especially common in brain-imaging studies, where we often find marginal results on a handful of subjects interpreted as telling us something about males and females in general. Listing some examples from earlier Language Log posts, here's a study of 9 boys and 10 girls used to argue that "Girls and boys behave differently because their brains are wired differently"; here's a study of 10 female and 10 male medical students at UCLA used to argue that "Women really do enjoy a good laugh as much as you do; they are just wired to focus on different aspects of humor." And here's a case where brain scans of 20 UCLA students were interpreted to tell us about the reactions of male and female voters to various presidential candidates. (That one was so preposterous that Nature administered an editorial rebuke.)

As yet another example of these rhetorical characteristics, let's take a close look at one of the studies that Hoag alludes to: Larry Cahill et al. "Sex-Related Hemispheric Lateralization of Amygdala Function in Emotionally-Influenced Memory", Learning and Memory 11: 261-266, 2004.

If you read this study online for yourself (which you can do, since it was published in an open-access journal), you'll find the usual things. The subjects were 12 male and 11 females, in their mid-twenties, who were apparently graduate students in and around Cahill's lab, and are of course taken without comment as valid proxies for all men and women everywhere. They were shown 96 scenes from the International Affective Picture System (in which the "arousing" pictures were all of negative emotional valence), and asked to indicate their "level of arousal" on a scale of one ("not emotionally arousing") to four ("highly emotionally arousing"). Two weeks later, they were shown an overlapping set of pictures and asked whether they remembered them; then their cerebral blood flow was measured using fMRI techniques.

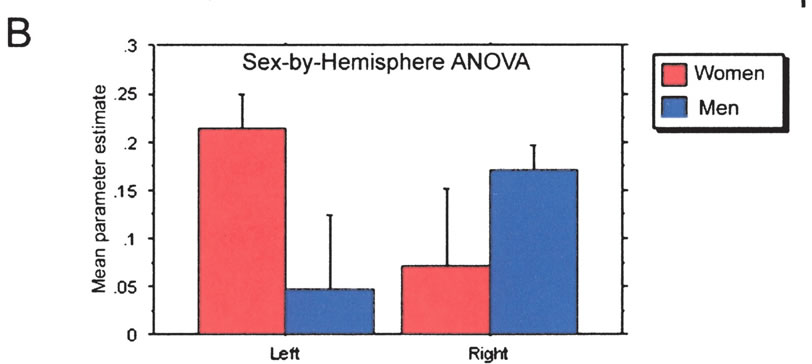

This paper doesn't really give us enough information to compare within-group and across-group variation in a quantitative way — instead, the authors just focus on showing us that there is a statistically significant difference between the sexes in their data. And because their analysis starts by zeroing in on the brain regions that happen to show the largest sex differences in their sample, it's hard to know what to make of the parameters that emerge from their modeling. But the confidence intervals shown for their ANOVA parameter estimates indicate that there were large overlaps in the distribution of individual-subject data, even though they've stacked the deck by modeling only the most sexually-divergent regions:

Figure 3 (B) Mean parameter estimate of amygdala activity in the left and right hemispheres, in males and in females. There was a significant interaction between sex and hemisphere in amygdala function by this measure (see text for additional details). Talairach coordinates for the peak voxel in each cluster were 22, -12, -15 for the effect in men, and -18, -12, -15 for the effect in women.

OK, now compare how Hoag describes this:

Cahill has found evidence that sex also influences how some brain regions are used. In brain-imaging experiments, he asked groups of men and women to recall emotionally charged images they had been shown earlier. Both men and women consistently recruited the amygdala – a pair of almond-sized bundles of neurons which make up part of the limbic system – for the task. However, the men enlisted the right side of it, whereas women used the left.

Cahill, speaking through Hoag, talks about what "the men" did and what "the women" did, as if all the men did one thing and all the women did another. But in fact his experiments present no evidence of this sort at all, but only evidence of a statistically-significant difference in group distributions, in a context where the within-group variation was (almost certainly) large compared to the average between-group difference.

Hoag, speaking for Cahill, adds another comment that happens to be not only misleading but technically false:

What's more, each group recalled different aspects of the image. The men recalled the gist of the situation whereas the women concentrated on the details. This suggests men and women process information from emotional events in very different ways, using different mechanisms, says Cahill.

This is technically false because that 2004 study of 23 California grad students, the one that we've just been talking about, didn't test anything whatever about recalling the gist vs. concentrating on the details. It does introduce some speculation on this point, referring us to another study of a different character:

Although the evidence to date points compellingly to the existence of a sex-related hemispheric lateralization of amygdala function in relation to memory for emotional events, it does not yet clarify what this lateralization means and what combination of biological (nature) and psychological (nurture) factors produced it. Answering these questions is now crucial for future investigation. One hypothesis we have pursued in this regard concerns hemispheric specialization in the processing of relatively global holistic aspects of a stimulus or scene versus processing of relative local fine-detailed aspects of the stimulus or scene. Substantial evidence points to a bias of the right hemisphere in processing global information and to a bias of the left hemisphere in processing local information. We combined this fact with the sex-related hemispheric specialization of the amygdala ("males right/females left") to detect a sex-related difference in the impairing effect of a drug that presumably impairs amygdala function in memory, the ß-adrenergic antagonist propranolol (Cahill and van Stegeren 2003). It appears that couching our understanding of amygdala function in terms of the hemisphere in which each amygdala operates is one method to begin to understand the functional significance of the sex-related amygdala lateralization in memory.

The reference that I've put in bold is to "Sex-related impairment of memory for emotional events with ß-adrenergic blockade", Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 79: 81-88, 2003. And contrary to Hoag's description, the experiments in question did not involve recalling aspects of the images used in Cahill's 2004 fMRI study. Instead, the 2003 paper combines data from two earlier (1994 and 1998) studies of "propranolol-induced impairment of memory for an emotionally arousing short story". And you won't be shocked to learn that the subjects were a small number of "students/professionals from our respective academic environments", taken as representive of males and females everywhere, and that again, we're the experiments found differences in group means that are fairly small relative to within-group variation.

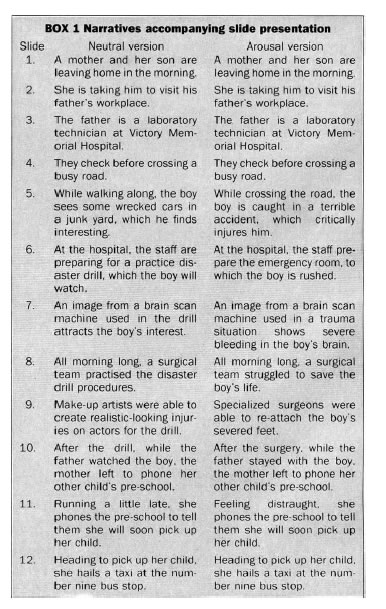

In the original 1994 and 1998 studies, the subjects took either 40 mg of propranolol or a placebo, and then were shown a story presented as a narrated show of 12 slides. The story came in two versions, a "neutral" version and an "arousing" version. The stories were divided into three phases, where the first phase was identical in the two versions, and the last phrase was almost the same, but phase 2 was quite different, with the "arousing" version having "emotionally arousing elements, involving severe injuries to a small boy in an accident". Here are the two narratives (from Cahill et al. 1994):

(I guess I should point out in passing that a story about a mother and her young son, whose head is smashed and feet are severed in an accident, is by no means a gender-neutral proxy for all emotional experience.)

Memory for the story was tested in a multiple-choice test a week later.

Cahill et al. 1994 used 36 students, divided (unevenly) into eight groups (neutral vs. arousing story, drug vs. placebo, male vs. female). Van Steegeren et al. 1998 used 75 students, again divided into eight unequal groups, using the same pictures and the same narrative, except omitting slide 7. For the 2003 re-evaluation, only the results from the "arousing" version of the story are considered. Thus the total number of subjects used in the re-evaluation of the two studies wound up being men/placebo=9, men/propranolol=11, women/placebo=13, and women/propranolol=13.

The results of these earlier studies were re-coded by having "four independent judges" view the stories and judge whether each question on the multiple-choice recall test "pertained to central story information or to peripheral detail". The crux of the experiment depends on what counts as "central story information" vs. "peripheral detail" in phase 2 of the "arousing" narrative, the part associated with slides five through nine — but unfortunately we're not told what the questions were, or which of them were considered to be "central" vs. "peripheral". This seems to me to make a difference — it's one thing if a "peripheral" detail is whether the surgeons worked all morning or all evening to save the boy's life, but another thing if it was considered "peripheral" whether they re-attached his severed feet or his severed hands.

Anyhow, here are the results:

Fig. 2. Multiple-choice test scores for phase 2 only from the Cahill et al. (1994) and van Stegeren et al. (1998) studies. The only average differences between placebo- and propranolol-treated subjects seen in both studies were a decrease in retention of central information in males given propranolol, and a decrease in retention of peripheral information in females given propranolol.

Again, differences between male and female group averages are apparently not very large compared to within-group variation. Cahill et al. don't give us the (simple) numbers that we would need to evaluate this quantitatively, but the "whiskers" in the graph represent "standard errors", which are the standard deviations for each group divided by the square root of the number of subjects.

It seems to me that it's reaching more than a bit to infer a sex difference in the emotional architecture of memory, based a pair of experiments involving a total of two dozen students and one story. Still, if Hoag's presentation of Cahill's interpretation is dialed back a few notches, this is valid and interesting science, and so is the rest of the work on the neuroscience of sex that she surveys. But as examples of the "real difference" between the sexes, this is pretty feeble stuff. So there's something that I really don't understand here — why was this a cover story, or for that matter a story at all?

The cynical answer is that "sex differences sell magazines". So far, I can't come up with a better one.

Jacob Christensen › Brains said,

July 26, 2008 @ 10:51 am

[…] Language Log (!) on brains and popular science reporting. This was written by Jacob Christensen. Posted on Friday, July 25, 2008, at 12:50. Filed under […]

ed kupfer said,

July 26, 2008 @ 4:36 pm

The cynical answer is that "sex differences sell magazines". So far, I can't come up with a better one.

The “sex differences revealed by fMRI” thing falls within the larger phenomenon of biological determinism. Stephen Jay Gould loved to catalogue various claims that the differences between groups of people was largely determined by their blood/genes/cranial bumps, each claim having no more support than the sex differences discussed by Mark above. There seems to be a need for differences among people to be explained by differences in their biology, possibly as a way of disclaiming responsibility for unequal status between these groups, and perhaps as a way of arguing that nothing should be done – since, after all, it is Nature’s way.

Tim Silverman said,

July 26, 2008 @ 5:49 pm

@ed kupfer

Perhaps part of essentialism about sex or other differences is due to a desire to produce a socially or morally acceptable account of unequal status, but I'm sure some of it stems from the same cause as essentialism in less controversial areas—the assumption that variations from a type are inessential to the basic phenomenon in question and simply disguise an underlying sharp difference, which needs to be brought into clear focus. This belief survives because it's often quite valid! Some of the differences between the sexes really are quite sharp. For instance, focussing on the precise degree of luxuriance of different men's beards would distract from the sharp divergence between men and women in the matter of facial hair.

(Similarly, in, say, physics, the existence of friction can distract attention from the simplicity of the underlying laws of motion, and the idealisation of a frictionless medium was necessary for the physics of motion to advance; more interestingly, the concept of biological species had to go through a zig-zag in its history: first, in the late seventeeth century, to eliminate the idea of a complete continuum between all living species, which would allow gnats to hybridise with giraffes, flies to emerge spontaneously from dung, human beings to be grown in jars from mandrake roots, etc), establishing sharp species boundaries—and then, during the nineteenth century, an acceptance of the essential reality of variation within species, and a more carefully controlled blurring of species boundaries in certain situations, particularly over time.)

Of course, even if you establish that some differences and essential, are real, you'd like to avoid imagining extra, fictitious differences, which only seem plausible because of the exaggerations of essentialism. Unfortunately, that is all too common a failing.

Sili said,

July 26, 2008 @ 5:49 pm

Breaking news! Boys and Girls are Equal in Math Ability!

Sadly that won't sell many papers.

The more of these stories you highlight, the more inclined I am to agree with Ben Goldacre, that old media are dead.

Of course I'm biased in that I get all my news from blogs, so I know more about the US elections than the university reshuffles at my own 'alma mater'.

2008-08-01 Spike activity | Psychology Blog said,

August 1, 2008 @ 5:58 am

[…] mighty Language Log has a great analysis looking at the fallacies of yet another popular piece on sex differences in mind and brain. The Economist has an article […]

Prescriptivity and appropriateness « Enlightened tradition said,

October 1, 2008 @ 3:32 am

[…] broadest possible sense. So its authors have taken on sex differences and biological determinism, science journalism, lolcats, and legal language. However, one of the best posting categories is "Prescriptivist […]

Visions of the Crash | The Loom | Discover Magazine said,

March 25, 2009 @ 1:23 am

[…] subject can, if necessary, rip a journalist a new one. I personally have been very influenced by Mark Liberman, a linguist at Penn, who has time and again shown how important it is for reporters to pay […]

Don Draper said,

April 21, 2010 @ 5:18 pm

Most psychological investigation is conducted using young students in universities as subjects. Am I to assume your opinion on all such research is it should be discounted?

[(myl) No, just that its nature should be recognized. In some cases, the limitation of the subject pool matters not at all. In other cases — probably more than is generally believed — it matters a lot. Across the human sciences in general, non-sampling error is a large (and mostly unacknowledged) problem.]

Visions of the Crash – Phenomena: The Loom said,

June 24, 2013 @ 11:21 am

[…] subject can, if necessary, rip a journalist a new one. I personally have been very influenced by Mark Liberman, a linguist at Penn, who has time and again shown how important it is for reporters to pay […]