Speed learns

« previous post | next post »

Most people know that amphetamines and related drugs have been prescribed over the years to increase alertness and to fight fatigue (although caffeine apparently works about as well and is safer), to improve morale (although during WWII the Germans restricted its use because of addiction problems), as a diet drug, and for medical conditions from "idiopathic anhedonia" in the 1950s to ADHD today. Those who don't know this history can learn about it from Nicholas Rasmussen's "Life in the Fast Lane", The Chronicle Review, 7/4/2008.

Even more people know that amphetamines have long been used for recreational purposes, among subcultures as diverse as beats, hippies, and bikers; and that non-prescription uses have recently been spreading in the U.S. among several paradoxically unrelated groups, including rural whites, homosexuals, and students at elite colleges.

But few people seem to have picked up on the fact that improved alertness, focus and mood may not be the only reasons that amphetamines are popular as a "study drug".

For more than a decade, evidence has been accumulating that low doses of amphetamines can improve certain kinds of learning and retention, independent of any other physiological effects. The mechanism is not clear, though a plausible candidate is the fact that amphetamine increases concentrations of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is "a physiological correlate of the reward prediction error signal required by current models of reinforcement learning". (See Hannah Bayer and Paul Glimcher, "Midbrain Dopamine Neurons Encode a Quantitative Reward Prediction Error Signal", Neuron 47(1): 129-141, 2005.)

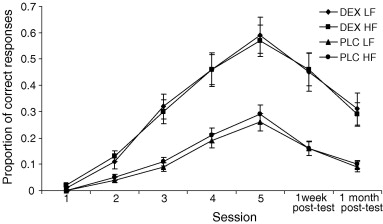

In the case of word learning in particular, the effects of amphetamine can be quite large. Here's a graph of some results from the most recent study that I've read — Emma Whiting, Helen Chenery, Jonathan Chalk, Ross Darnell and David Copland, "The explicit learning of new names for known objects is improved by dexamphetamine", Brain and Language 104(3) 254-261 2008:

Fig. 1. Proportion of correct responses on the recall task according to frequency and participant group.

There were 37 subjects, 11 males and 26 females, between 18 and 34 years old. Their task was to learn 50 new non-word names (e.g. flane, neech) for familiar objects, represented as line drawings. The critical stimuli were embedded among a larger set of stimuli (including drawings of "novel objects", for which the results were described in a different paper, cited below). The 50 critical objects were divided into two groups — 25 whose original names were high-frequency words (i.e. words that occur often), and 25 whose original names were low-frequency words.

There were five learning sessions on five consecutive mornings. One group of 19 participants (the "DEX" group) got two 5-milligram tablets of dexamphetamine about two hours before the learning session, while the other group of 18 subjects (the "PLC" group) got two placebo tablets. During a learning session, each participant saw a sequence of pairs of drawings and names. After each learning, the participants were tested on recall (ability to produce the name for an object) and recognition (ability to determine whether an object/name pairing is correct). Additional recall and recognition tests (without any drug administration) were given one week and one month later.

In the legend for the graph above, "DEX LF" refers to performance of the DEX group on the objects whose original names were low-frequency words, whereas "DEX HF" refers to that group's performance on the objects whose original names were high-frequency words. The two "PLC" lines represent the performance of the group that got the placebo. (If you're having trouble with the rather tiny plotting characters, the two upper lines represent the performance of the DEX group.)

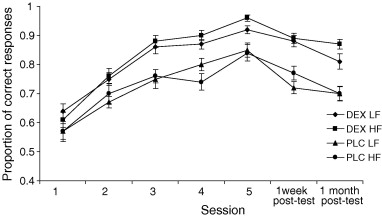

The name recognition task showed a smaller percentage effect (both absolute and relative):

Still, a difference of about 15 percentage points in recognition scores, tested a month after the training stops, is plenty big enough to be recognized by those who (ab)use such drugs as study aids, and to motivate them to persevere in such use despite the considerable dangers.

Whiting et al. used a variety of other physiological and psychological measures to support their conclusion that "new word learning success was not related to baseline neuropsychological performance, or changes in mood, cardiovascular arousal, or sustained attention". There's an unavoidable problem in such studies — as the authors explain, "due to the nature of dexamphetamine, participants may not have been performing in a fully blinded manner, despite the use of a placebo control". I'd be curious to know what would happen if caffeine tablets were used instead of placebo tablets.

The earlier literature on this subject goes back to 1993. A sample: E. Soetens et al., "Amphetamine enhances human-memory consolidation", Neuroscience Letters 161(1): 9-12, 1993; Caterina Breitenstein et al., "D-Amphetamine Boosts Language Learning Independent of its Cardiovascular and Motor Arousing Effects", Neuropsychopharmacology 29(9): 1704:1714 2004; Emma Whiting et al., "Dexamphetamine enhances explicit new word learning for novel objects", The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 10:805-816 2007.

The explicit motivation of recent research on this topic has been to improve the treatment of aphasia and other clinical disorders of naming (despite obvious issues with possible hypertension side-effects). This was explicitly tested by Walker-Batson et al., "A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of amphetamine in the treatment of aphasia", Stroke 32(9), 2093–2098, 2001; and Emma Whiting et al., "Dexamphetamine boosts naming treatment effects in chronic aphasia", Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 13: 972-979, 2007; and surveyed in Friedemann Pulvermmuller and Marcelo Berthier, "Aphasia therapy on a neuroscience basis", Aphasiology 22(6): 563-599, 2008.

I've seen very little explicit discussion of the role of amphetamine in general,, non-clinical cognitive enhancement, although it's mentioned in Nick Bostrom and Anders Sandberg, "Cognitive Enhancement: Methods, Ethics, Regulatory Challenges", Science and Engineering Ethics, 2007. This might be because of concerns that any positive evaluation of these drugs will contribute to their abuse — though the widespread and increasing diagnosis of ADHD, with associated prescription of Ritalin and Adderall, doesn't seem to be inhibited by such considerations. In particular, there's no mention of this issue in Nicholas Rasmussen's interesting new (2008) book On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine. And college students who use prescription Ritalin or Adderall as a study aid tell me that they believe that they get general cognitive enhancement from these drugs, based on their own experience rather than from reading the literature in neuropsychopharmacology.

I should add that I don't recommend amphetamines as an aid to language learning. I've never taken any drugs in this family myself, and don't intend to start, since the same dopaminergic reward system that may perhaps facilitate learning also clearly leads to easy addiction and serious withdrawal effects. You don't have to take the word of anti-drug crusaders for this — you can listen to generally pro-drug-legalization people like Andrew Sullivan, or frankly pro-drug people like Allen Ginsberg (from an interview with Art Kunkin, Los Angeles Free Press, December 1965):

"Let's issue a general declaration to all the underground community, contra speedamos ex cathedra. Speed is antisocial, paranoid making, it's a drag, bad for your body, bad for your mind, generally speaking, in the long run uncreative and it's a plague in the whole dope industry."

But it doesn't help prevent drug abuse to pretend that the positive effects don't exist.

And it would be nice if the psychopharmacologists could figure out how to get the cognitive enhancement without the addiction — though if both effects are mediated by the brain's "reward prediction error signal", that may be hard to do.

Rob Gunningham said,

July 22, 2008 @ 7:40 am

Mark Liberman: I've never taken any drugs in this family myself…

On the other hand, now we know how you get to post long pieces by 6:57 am.

Stephen Jones said,

July 22, 2008 @ 8:12 am

Back in the early seventies you could still get speed legally over the counter in the UK if you bought an asthma drug called 'Dodo'. Presumably the name seemed so inappropriate that it fooled the regulatory authorities.

John Cowan said,

July 22, 2008 @ 9:45 am

Or as we used to say back in the day: Speed kills.

jason braswell said,

July 22, 2008 @ 9:54 am

This is a great blog, and I by no means am trying to question your objectivity, but I still feel the bit at the end about the dangers of amphetamines is a bit overplayed and sort of a lame nod to the "establishment", if you'll forgive the phrase.

Doing uncontrolled amounts of amphetamines will no doubt harm you, but I think you'd be hard-pressed to show evidence of substantial risk in a normal, healthy person taking them at prescription-level doses.

(For the record, I take prescription Adderall and find it helps tremendously with school, work, and Japanese learning.)

Jimboooo! said,

July 22, 2008 @ 11:46 am

There was a road safety campaign when I was in school that went "Kill your speed, not a child.". This was invariably read as "Sell your child, buy some speed.".

Happy days.

Jonathan said,

July 22, 2008 @ 11:57 am

I took marax in college for asthma, but only in the spring. I remember one spring quarter when I would feel the onset of an asthma attack virtually every night, take one of those pills, and then study for a few hours, say between 10 and 2. Pretty soon I was taking them even when I didn't really have an attack coming on. I had French, German, and Latin that quarter, plus a few literature classes in Spanish and English. What was in those pills? Ephedra for one thing.

Don Sample said,

July 22, 2008 @ 12:39 pm

Still, a difference of about 15 percentage points in recognition scores, tested a month after the training stops, is plenty big enough to be recognized.

An example of how how you look at the numbers can effect your result. If you look at the proportion of incorrect responses, instead of the correct responses, it goes from 30% for the people not taking the amphetamines, to 15% for those who are: a drop of 50%. The people who took the drug made half as many mistakes.

John Lawler said,

July 22, 2008 @ 12:58 pm

See

Guiora, A., B. Beit-Hallahmi, R. Brannon, C. Dull, and T. Scovel. 1972. "The effects of experimentally induced changes into ego states on pronunciation ability in a second language: an exploratory study." Comprehensive Psychiatry 13: 421-428.

Guiora et al demonstrate that vocabulary learning in a (real) foreign language is enhanced at the 1.5 oz alcohol level — but depressed above that, and not available on an empty stomach, either — a fact that many language students have noted anecdotally as well.

The authors theorize that it is the relaxation of social inhibitions that occurs with alcohol that contributes to the enhancement. This probably wouldn't show up in a laboratory setting with nonsense words in one's native language.

carla said,

July 22, 2008 @ 2:12 pm

Only tangentially related – but when I was in college, a close friend's mother told us a sort of cautionary tale about using amphetamines to help get through finals. The tale is almost certainly embellished, if not entirely apocryphal, but it had a twist that hard-studying language geeks are sure to find very resonant; my friend and I certainly did.

When my friend's mother was a senior at our alma mater, she told us, she took amphetamines to help her get through finals. She had a double-major in French and Russian, and had a particular stressful finals season with comps in both languages.

She stayed up all night cramming for her French comps, and when she took the exam she felt bright, focused, and sharp. She knew the answer to every question and wrote thoughtful, analytic essays on each point raised. She was sure she'd aced the exam.

It was only when her French advisor called her into his office some days later that she came to realize she had written the entire exam in Russian.

Nathan said,

July 22, 2008 @ 2:13 pm

Reminds me of XKCD's Ballmer Peak.

kyle said,

July 22, 2008 @ 2:35 pm

only vaguely related, but there is ongoing research at Penn's Cognitive Neuroscience Center relating to the issue of the effects of stimulants on creativity (the paradigm they're using is a double-blind test with groups either receiving, or not, a prescription stimulant, and then asked to generate novel uses for common household objects). there's been some thoughts that ADD/ADHD medications might stifle creativity, and my experiences as an overmedicated 90s child suggest that it is so … i did little but read and study during the years i was prescribed a low dose of ritalin, and the second i stopped taking it, my grades dropped slightly, i started spending 5 or more hours every day writing pop music, and got interested in the opposite sex for the first time in my life. i sort of lost interest in my Latin studies, though.

Mark Liberman said,

July 22, 2008 @ 3:10 pm

jason braswell: Doing uncontrolled amounts of amphetamines will no doubt harm you, but I think you'd be hard-pressed to show evidence of substantial risk in a normal, healthy person taking them at prescription-level doses.

I didn't mean to slam prescription use of Ritalin and/or Adderall. One of my sons had them prescribed for many years, and they clearly did him some good and (and far as I can tell) no harm.

But a logical inference from studies like those I described might be that everyone should take them all the time — or at least, that everyone who is doing any sort of associative learning should. I'm much less sure that this would be a good idea, though I don't have any arguments to offer beyond general pharmacological conservatism — and the opinion that a substantial fraction of the prescribed dosages would be hoarded, re-sold, crushed and snorted, for reasons having nothing to do with improved learning, and with results that would sometimes be bad.

Chris said,

July 22, 2008 @ 4:36 pm

I believe Provigil is supposed to be non-addiction-forming. My PA still wouldn't proscribe it for me, though.

[(myl): Provigil (the generic term is modafinil) isn't an amphetamine, as I understand it; and (as far as I know) its effects on learning haven't been tested.]

Faldone said,

July 22, 2008 @ 7:19 pm

Now we know the real reason for the end of College Bowl. It was the performance enhancing drug scandal.

2008-08-08 Spike activity | Psychology Blog said,

August 8, 2008 @ 6:15 am

[…] Log has an excellent piece on another reason why the amphetamine methylphenidate (Ritalin) may be popular as a study drug – apart from its boost to wakefulness it might actually […]

AndrewK said,

August 2, 2009 @ 2:37 am

Well it is nice to see the effectiveness laid out so cleanly,

I have been diagnosed with ADHD at age 46, despite a moderately successful career so far. I am mostly using it to learn to react to adverse events with equanimity. I am happy that I am being properly supervised. I would not recommend tangling with any pharmacologically active agent without proper monitoring. This is especially important when the mind is involved as we can lose our objectivity so easily.